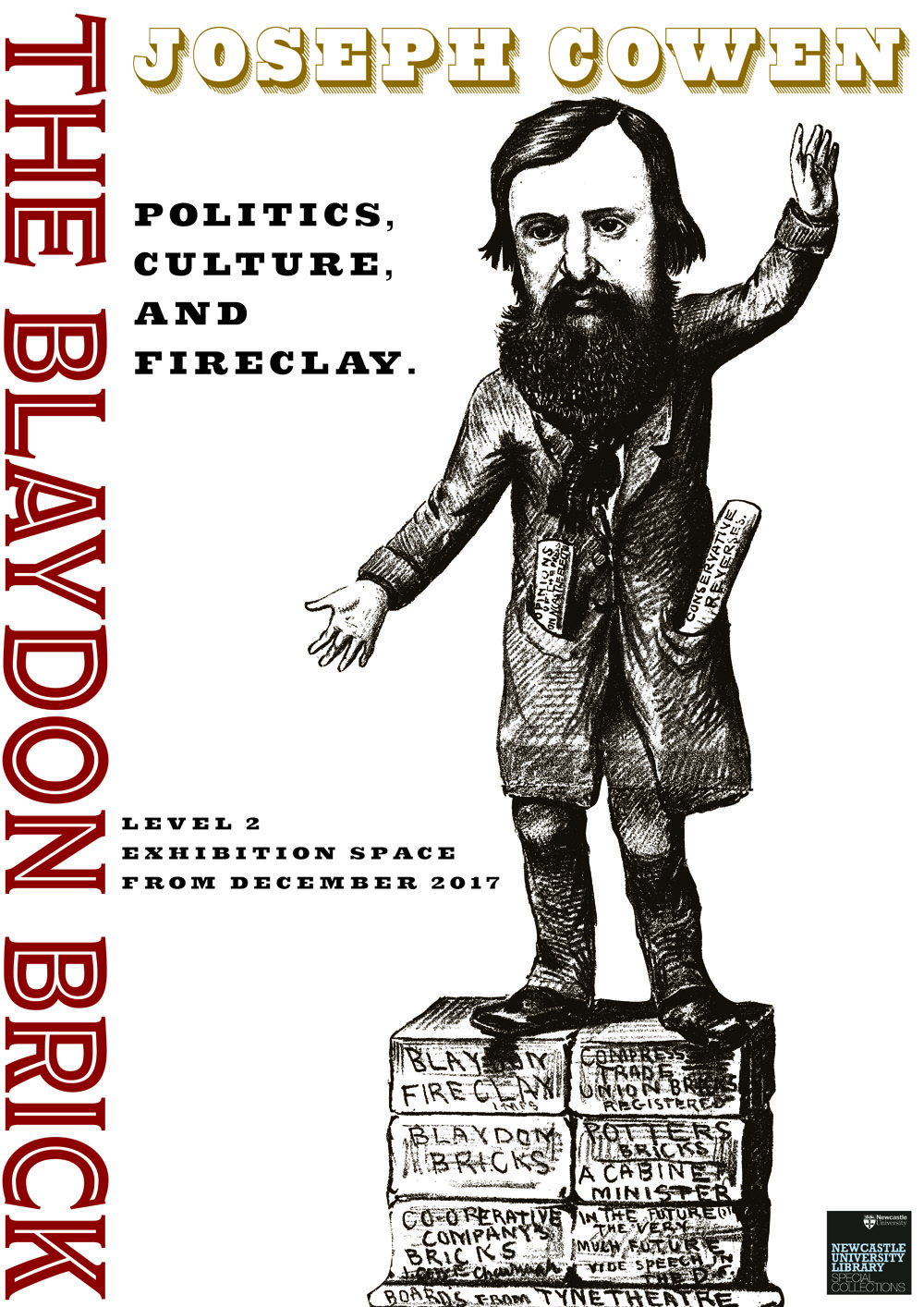

Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections holds pamphlets and books that were formerly owned by Joseph Cowen Jnr. (1829-1900). Joseph Cowen was an M.P. for Newcastle upon Tyne, he supported cultural institutions in the region. The family brickworks was inspired by his nickname, ‘the Blaydon Brick’.

The below material are highlights from the ‘Blaydon Brick: Joseph Cowen‘ exhibition which was on display in the Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne. It draws upon the pamphlets and books as well as portraits, speeches and cartoons from other collections, to explore Joseph Cowen’s political career.

The Cowens

The Cowen family moved from Lindisfarne (Holy Island) in Northumberland to Stella on Tyneside soon after the Reformation and dissolution of the monasteries. Looking for a safe haven, the Catholic Cowens found themselves in the shelter of the prosperous Tempest family of Stella Hall, near Blaydon. Eventually, after establishing his family and various successful businesses around Blaydon Burn, Joseph Cowen Senior would buy Stella Hall…

The Cowens found work at Sir Ambrose Crowley’s steelworks at Winlaton. Crowley was an exceptional employer for that era, providing free schooling for the children of the village, and paying for a doctor to treat his employees and their families. He also established a fund to support workers forced to stop working due to age or disability. Crowley’s practices clearly had an impact on the Cowens. The factory closed in 1816.

Photo of Crowley tombstone.

From M. W. Flinn, Men of Iron: The Crowleys in the Early Iron Industry (1962) (338.273 FLI, Philip Robinson Library)

Joseph Cowen Senior (1800-1873) was born at Greenside, near Blaydon, and

worked as a chain maker in Ambrose Crowley’s factory. Interested in the social conditions of his fellow workers, he became a member of ‘Crowley’s Clan’, the tightly-knit group of Crowley’s employees protecting workers’ rights.

By 1850, Joseph Cowen Senior had become a successful businessman and bought Stella Hall, the former home of the Tempest family which had offered his ancestors a refuge during the Reformation.

Stella Hall was essentially an Elizabethan house with 18th century additions. The last member of the Cowen family, Jane, died in 1948 and the house was demolished in 1953. The only remaining part of the Hall is now known as the Grade II-listed Stella Hall Cottage.

Cowen bookplate. The Library of Reason

Most of the books in our Cowen Tracts contain his engraved booklate, showing a Bewick-like view of Stella Hall with the spire of Newcastle’s St Nicholas’ Casthedral in the background.

In 1853 Cowen was elected to the Newcastle Municipal Council and became Liberal MP for the city in 1865.

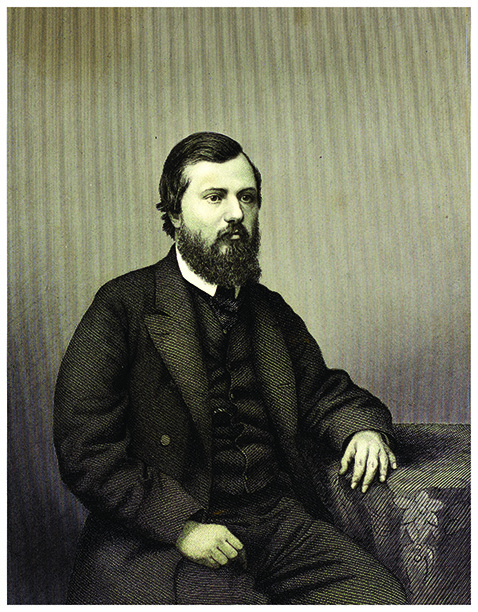

His son, Joseph Cowen Junior (1829-1900) was born at Blaydon Burn House, Blaydon. After private education in Burnopfield, he attended Edinburgh University, where he became interested in European revolutionary political movements, influenced by his teacher, Scottish preacher Dr. John Richie. Richie was a fearless radical and fiery orator and influenced Joseph’s social conscience.

The Blaydon Brick

In 1828, Cowen Senior went into business with his brother-in-law Anthony Forster to manufacture fire bricks, under the company name Joseph Cowen & Co. The business quickly developed, helped by the superior quality of the local fireclay.

On returning from Edinburgh, Joseph Junior took a very active role in the family business and workers’ conditions. His developing interest in domestic politics and revolutionary European politics was also evident; his views were much stronger than his father’s.

Cowen Junior became a frequent speaker at workers’ trade clubs and mechanics’ institutes, reputedly speaking at every colliery village in Northumberland and Durham. His skills as an orator were widely recognised later in his life when he became an MP. He himself built up an extensive library of speeches by others, and his own speeches were collected in various volumes.

From the Nineteenth Century, industrial development expanded rapidly along the Blaydon Burn to include a number of industries related to the processing of coal. The supply of cheap local fuel and good transport links led to the development of coke works, steelworks, iron foundries, and brickworks, making Blaydon Burn one of the most industrialised parts of the region.

Cowen bricks, made from the superior clay found in the area, can still be found in parts of Blaydon Burn Nature Reserve. They are easily recognisable, with the prominent ‘COWEN’ stamp.

Photograph of the Cowen brick walkway at Roche Harbour, San Juan Island, Washington, USA Cowen bricks were exported all over the world and can still be seen in many locations.

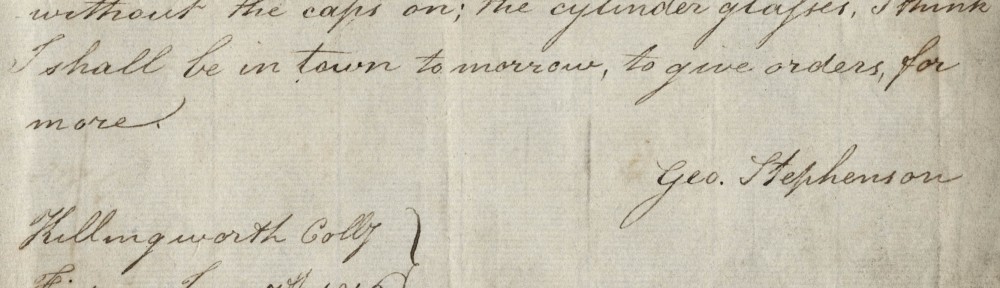

Short in stature and uncouth in appearance, Cowen spoke with a distinctive Tyneside burr. When he entered Parliament in 1874, after the death of his father, his manner initially shocked members of the House of Commons. Eventually, his genuine eloquence established him as one of the best-known politicians in the country. He became known as the ‘Blaydon Brick’ – a reference to his physical appearance, attitude, and, of course, the family business in Blaydon.

This satirical cartoon (below) shows Cowen astride his political ‘support’ – various bricks named after his extensive business interests (bricks, fire clay, the Tyne Theatre, and the Newcastle Daily Chronicle).

‘After the ballot’ [A volume of printed ephemera, broadsides, posters, cartoons, referring to election in Northumberland, Necwcastle and Tyneside divisions, 1826-1931] (RB 942.8 ELE Quarto, Rare Books Collection)

Cowen and Domestic Politics

Cowen, a formidable political force in the North East, represented Newcastle upon Tyne as its Liberal MP from 1874–1886. In 1858 he established the Northern Reform Union and, in 1867, was Chair of the Manhood Suffrage Committee. These organisations shared a common ambition to bring about reform, particularly through extended enfranchisement (the right to vote). On Tyneside particularly, Cowen helped to politicise the miners and to bring reformers from the middle and working classes together. (He counted Robert Spence Watson, a social and education reformer from Bensham Grove in Gateshead, among his friends.)

Cowen encouraged political debate and persuaded communities to participate in local, national and even international political struggles. His independence, and his support of an Irish Parliament and Home Rule, brought him into conflict with the Liberal caucus and split the party into radical and moderate factions.

The death of the incumbent MP, Joseph Cowen Snr., occasioned a Newcastle upon Tyne by-election on 14 January 1874.

The by-election was won by the Liberal candidate, Joseph Cowen Junior, who defeated the Conservative, Charles Frederic Hamond, with a majority of 1,003. This cartoon depicts the scales of justice weighing the votes, with Hamond tying casks of beer to the

Conservative scalepan in a bid to tip the balance.

This is significant because the Liberals (led by William Ewart Gladstone) were not united: the education policies upset nonconformists; trade union laws and restrictions on drinking upset the working-class; and the party was divided over Irish Home Rule. Parliament was dissolved just nine days after the Newcastle by-election, prompting another contested election. Again Cowen won but, this time, those supporting a more moderate faction of the Liberal party supported Thomas Emerson Headlam. Despite winning the popular vote, the Liberals lost the general election to the Conservatives (led by Benjamin Disraeli). Newcastle upon Tyne was one of few constituencies to remain under Liberal control.

‘Weighed in the balance and found wanting’

[A volume of printed ephemera, broadsides, posters, cartoons,

referring to elections in Northumberland, Newcastle and Tyneside

divisions, 1826–1931] (RB 942.8 ELE Quarto, Rare Books Collection)

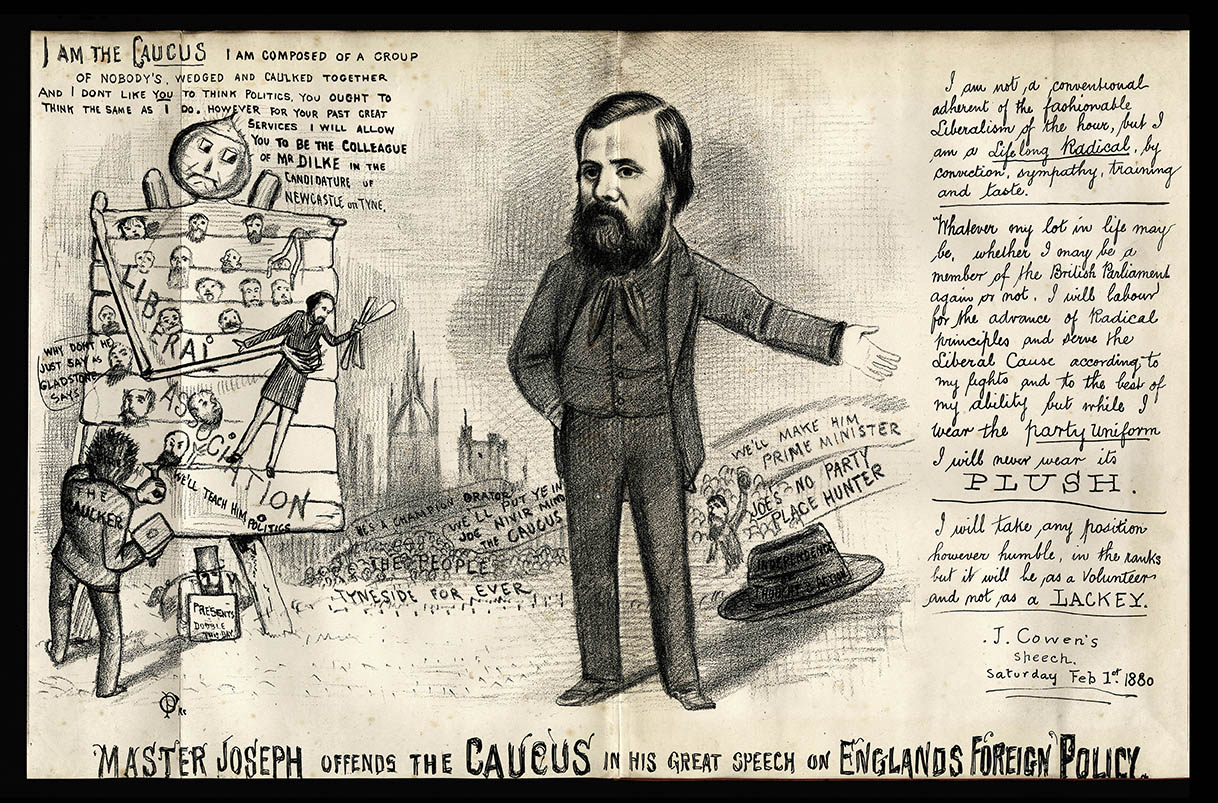

In this cartoon (below), the caucus is depicted as a group of insignificant people who want their candidates to think and speak as they do. The caucus is backing another Liberal candidate, Ashton Wentworth Dilke, but is prepared to offer Joseph Cowen a role as Dilke’s colleague. The people of Tyneside, however, are firmly and loudly behind Cowen. Cowen’s oration, 1 February 1880, is a rejection of Gladstone’s Liberalism in favour of the pursuit of radical principles.

‘Master Joseph offends the caucus…’

[A volume of printed ephemera, broadsides, posters, cartoons,

referring to elections in Northumberland, Newcastle and Tyneside divisions, 1826–1931] (RB 942.8 ELE Quarto, Rare Books Collection)

Cowen and International Politics

In the wider political sphere, Cowen was an ardent supporter of European revolutionary movements. He championed their causes in Britain through the press and fundraising campaigns, and directly assisted their movements by smuggling propaganda and clandestine material into Europe in consignments of bricks. He counted many of the key revolutionaries of the time as his friends, and organised their visits to Tyneside.

Despite his radical views, Cowen was also a supporter of British imperial ambitions. As with his domestic politics, his views on imperial policies caused considerable tension between him and the Liberal Party. The Russian Empire in particular was seen by Cowen as being not only a threat to the British Empire, but also to the freedom of other European peoples.

Cowen delivered a speech in the Town Hall, Newcastle upon Tyne (1880) titled ‘The Foreign Policy of England‘ (M082 PAM Sundries III, John Theodore Merz Collection) This speech by Cowen highlights his antagonism towards the Russian Empire and his call for freedom for peoples oppressed by the Russians, particularly the Poles.

Cowen helped Polish-Hungarian refugees who had arrived in the country in 1851, including a group who settled on Tyneside. He organised public meetings, speeches, and collections for Polish exiles. Cowen was also involved in more clandestine activities, such as assisting the efforts of the Polish Democratic Society, a radical political organisation, by arranging for funds, arms, and propaganda to be smuggled to Eastern Europe. He destroyed much of his correspondence with the revolutionaries in order to obscure his involvement in their affairs.

Cowen came under attack within the Liberal Party over his imperialist views. For example, he supported the Tory government’s pro-Ottoman stance during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), as the Ottomans were a useful counterweight to Russian power. However, the Liberals strongly campaigned against Ottoman support due to atrocities committed in Bulgaria by Ottoman forces.

In this Liberal cartoon (below), the ‘Russian Bear’ ridicules Cowen for his apparent hypocrisy as ‘Freedom’s Priest’. The Bear remarks that, while Cowen may comment on the Russian treatment of the Poles, Cowen supported ‘the Jew’ to ‘rob and murder little Afghan’. The Bear was referencing Jewish Tory Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80).

‘Birds of a Feather’

[A volume of printed ephemera, broadsides, posters, cartoons, referring to elections in Northumberland, Newcastle and Tyneside divisions, 1826–1931] (RB 942.8 ELE Quarto, Rare Books Collection)

Cultural Activities: The Route to Citizenship

Cowen’s desire for an expanded franchise (right to vote) also manifested itself through the facilitation of cultural activities. Cowen believed in the necessity of an educated democracy and saw participation in cultural activities as pathways to full citizenship. He thought that self-improvement, through intellectual activities and enjoyment of performing arts, would lead to an expanded democracy.

Cowen served on the committee of the Arts Association of Newcastle upon Tyne and took leading roles in the founding of the Tyne Theatre and Opera House and Newcastle Public Library Service. By the early-Twentieth Century, the working-class had a prominent culture in Newcastle.

Joseph Cowen recognised that the press could be an effective way of promoting his radical brand of politics. He bought the Newcastle Chronicle in 1859. The newspaper was already well-established as a political vehicle, with a middle-class readership and influence over the Whigs. (The Whigs were a political party that, by the Nineteenth Century, drew support from emerging industrial interests and supported the supremacy of Parliament over the monarchy, free trade, Catholic emancipation, the abolition of slavery and extending the vote.) He invested heavily in the paper, including a new rotary press, and re-launched it as the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle.

The repeal of tax on advertisements, duty on paper, and stamp on news led to the increased production of newspapers and Cowen took full advantage. Sports reports, serialised literature, and features on mining communities and co-operatives attracted new readers: by 1873, daily sales exceeded 40,000. But Cowen was on a mission to inform and educate his readers and kept them up to date with issues such as the Polish struggle against Russian oppression and with the fight for Home Rule in Ireland.

Cowen used the newspaper to: garner support for the establishment of a College of Science in Newcastle; sell the benefits of his Co- Operative Union; publicise the take-up, by prospective employees, of shares in the Ouseburn [engineering] Works; highlight the plight of female agricultural workers; subsidise the Italian revolutionary general Garibaldi; and, generally, to promote radical causes. The Chronicle press allowed him to influence public opinion significantly.

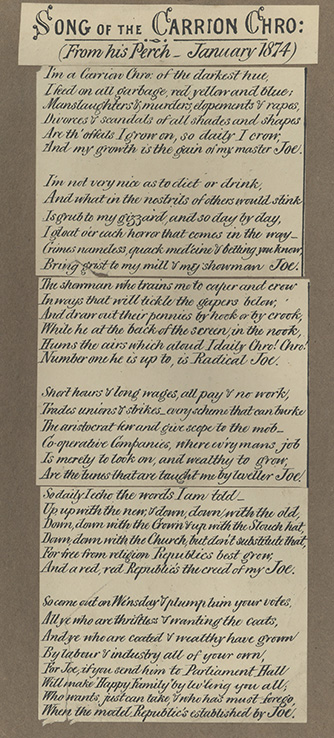

The ‘Carrion Chro’ verse (below) plays on the word ‘crow’ to make a derogatory statement about Cowen’s Chronicle. Carrion crows are noisy birds that perch on vantage points and beat their wings slowly but deliberately. They actively harass predators and competitors and can engage in mobbing behaviour. Carrion crows are scavengers. In making this comparison, the author of the poem accuses Cowen of running stories that feed on a festering underlife: ‘Manslaughters & murders, elopements & rapes, / Divorces & scandals …. quack med’cine & betting’. The Chronicle, says the poem’s author, is Cowen’s vehicle for engaging ‘the mob’.

‘The Carrion Chro’

[A volume of printed ephemera, broadsides, posters, cartoons, referring to elections in Northumberland, Newcastle and Tyneside divisions, 1826–1931] (RB 942.8 ELE Quarto, Rare Books Collection)

The theatre opened on 23rd September 1867 with Dion Boucicault’s Arrah-Na-Pogue: a melodramatic tale of misadventure, villainy and romance, set during the Irish rebellion of 1798. The play’s theme – the struggle for Irish independence – is aligned with Cowen’s support of Irish nationalists. It played to full houses.

Stanley managed the theatre with a stock company until 1881. During this period, and in the decades to come, the theatre became a venue for staging bold, socially-motivated dramas, as well as functioning as a forum for controversial debates. Richard William Younge managed the theatre in the 1880s and provided free shows for poor children and members of the bird conservation society, the Dicky Bird Society.

Photograph, Tyne Theatre, Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, c.1900 (008908, Newcastle City Libraries)

In 1870, Dr Henry Newton took up his late father’s campaign for a public library. Joseph Cowen’s commitments to democracy and to educating the people motivated him to take a leading role in supporting the cause, especially through the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle. The lending library was temporarily housed in the Mechanic’s Institute until the opening of the first public library building in Newcastle, in 1880. This library was built on New Bridge Street West and was later extended with the construction of the Laing Art Gallery.

Newcastle was late in establishing a public library. The Public Libraries Act had been passed in 1850, with The Royal Museum and Public Library in Salford being the first to open in the UK, in 1850. Philanthropists (people that perform deeds for public good, or ‘dogooders’) seeking to ‘improve the public’ campaigned for public libraries in the face of opposition from the Conservatives, who feared the cost implications and the potential for social transformation.

Newcastle’s Library of the Literary and Philosophical Society had been established as a conversation club in 1793 but it has always been a subscription library. When it opened, the rate of membership was one guinea (roughly £58.83 in today’s spending worth). This was beyond the financial reach of working people. In 1855, the rate for using a public library was one penny and, in 1919, reform of the public libraries made them free to use.

Joseph Cowen was the first person to borrow a book from the new library. The book that was issued to him was On Liberty by J.S. Mill, 1859 (M323.44 MIL, John Theodore Merz Collection) in which the philosopher J.S. Mill sets out his ideas on the relationship between authority and liberty. It was a hugely influential work that continues to underpin liberal political thought today.

Cowen’s Legacy

Cowen could be said to have advanced the primacy of urban environments. He saw the concentration of people as a strength because larger populations were less vulnerable to being oppressed by the elite. Industrialised cities, he said, brought the benefits of economic growth, science and medicine and the possibilities of liberty and social elevation to everyone.

As the MP for Newcastle upon Tyne, he represented the town and then city (Newcastle became a city on 3 June 1882). However, in campaigning for better housing and social welfare reform, in championing workers’ unions and in encouraging self-improvement through the provision of Co-operatives, libraries, places of learning, mining and mechanics institutes and public entertainment, he arguably embodied the spirit of Newcastle.

Cowen’s Library

Books and pamphlets that were owned by Joseph Cowen were given to Newcastle University in 1950. Almost 2,000 pamphlets from his private library have been kept together in Special Collections, in a collection called the Cowen (Joseph) Tracts.

Pamphlets were an effective form of public debate because they could be widely distributed and their authors could hide behind anonymity. The Cowen Tracts discuss such issues as: Irish politics; foreign policy; women’s rights; education; and public health.

These tracts, like all of our Special Collections holdings, can be used by anyone that has an interest – even if they are not a member of the University and its library. The books, many being literary works, were dispersed across various collections as well as the general holdings of the University Library.

Lifelong Learning Centre

Joseph Cowen lends his name to the Joseph Cowen Lifelong Learning Centre, in Newcastle. The Centre has changed its location several times over the course of its existence. In the 1960s, it was based at Barras Bridge, in the building seen on the right of the photograph below.

Today, the centre has charitable status and aims to provide opportunities for lifelong learning across the North East. It achieves this through a programme of talks, workshops and visits (called Explore) that are open to all adults, irrespective of their knowledge and qualifications.

The link between Cowen and education is a strong one: he had been Chairman of the Education League in Newcastle; and advocated for the availability and quality of education for all, most notably for non- Sectarian education and extending education beyond primary school for working class children. He donated money to support Mechanics’ Institutes, reading rooms and libraries. He also played a role in the establishment of a College of Physical Science in Newcastle (now Newcastle University).

Joseph Cowen Chair of English Literature

The first Chair of English Literature was established at Newcastle University (then it was known as the College of Physical Science) in 1898. It is an endowed chair, founded by the family of Joseph Cowen. Ever since 1909, it has been officially called the Joseph Cowen Chair of English Literature.

Peter Ure held the Joseph Cowen Professor of English Language and Literature at Newcastle University 1960–1969.

Electoral Reform

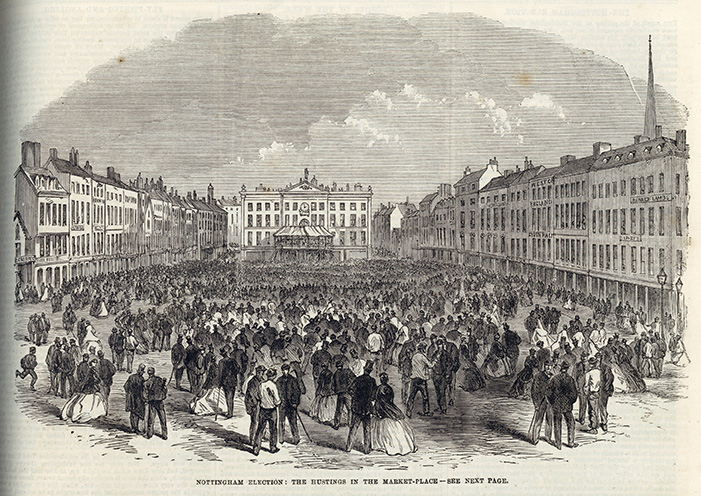

Cowen demonstrated his commitment to democracy by being a staunch advocate of electoral reform, particularly in 1867 when he was heavily involved in the campaign for the Second Reform Bill. He was also a vocal supporter of women’s suffrage at the time of the 3rd Reform Bill. He played a leading role in securing an amendment to the Bill when it was discovered that it disadvantaged miners who could not meet the complex property qualifications for the vote.

‘Nottingham election: the hustings in the Market-Place’ in The Illustrated London News (May 19, 1866) (19th C. Coll. 030 ILL Folio, 19th Century Collection)

Community Relations

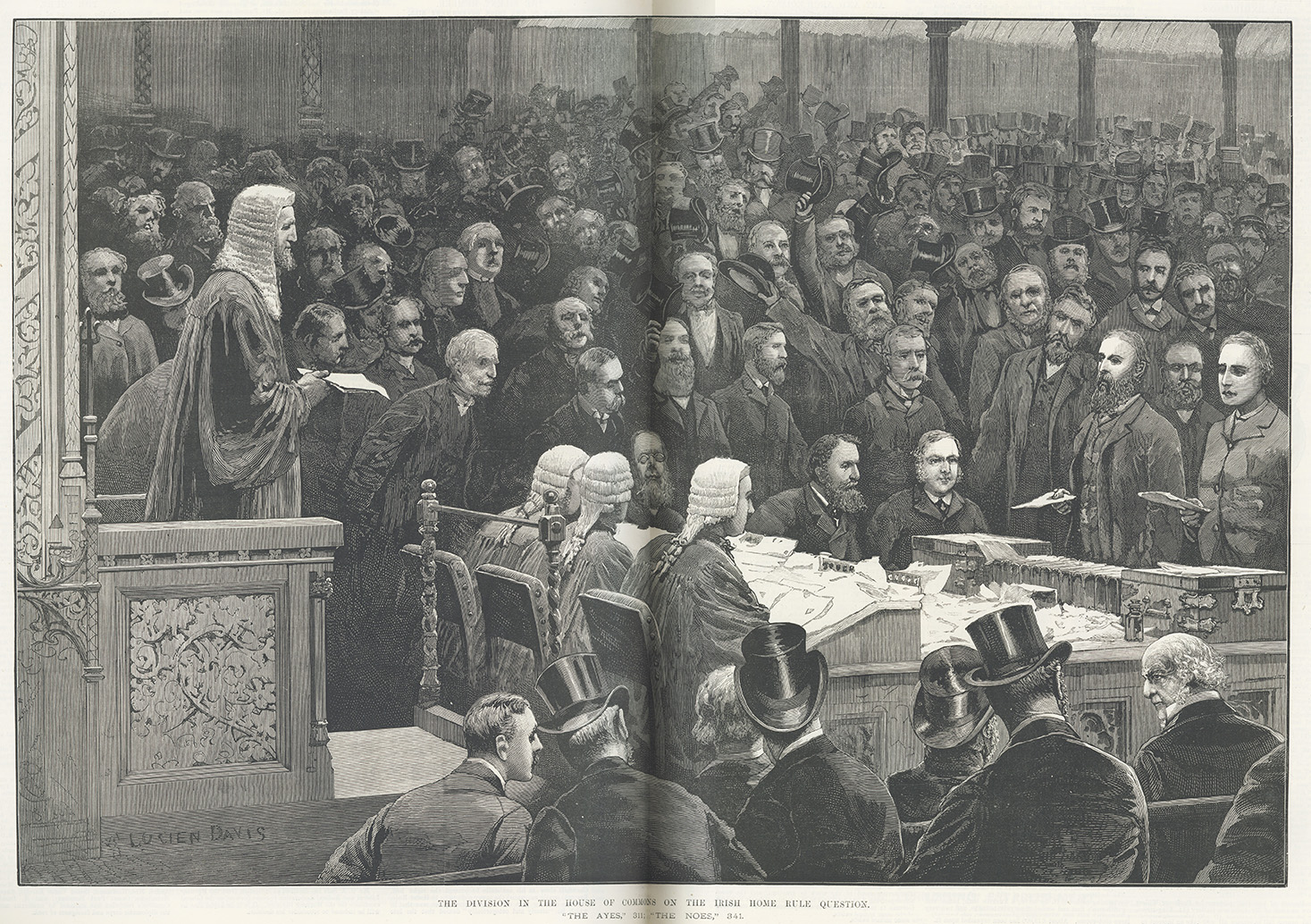

Cowen fostered harmonious relationships between local people and ‘minorities’ who settled in the region (most notably the Irish community who experienced extreme prejudice and hostility in many other British towns and cities – Liverpool, Glasgow and London, for example). He challenged the various Irish Coercion Acts in the House of Commons in the early 1880s and pledged his support for Irish Home Rule long before Gladstone presented it as official Liberal policy. His attitude to migrants remains a cornerstone of the region’s reputation for fairmindedness and tolerance.

‘The division in the House of Commons on the Irish Home Rule’

question’ in The Illustrated London News (June 12, 1886) (19th C. Coll. 030 ILL Folio, 19th Century Collection)

Statue of Joseph Cowen

Cowen is commemorated by a bronze statue in Newcastle city centre, which can be found opposite the Tyne Theatre, at the junction of Westgate Road and Fenkle Street. The statue was erected in 1906 and was funded by public subscription. It was created by renowned Scottish sculptor John Tweed.

We would like to thank Dr Joan Allen for her contribution to this

exhibition.