The Military Service Act Fully and Clearly Explained, by Philip Snowden (MP), 1916 (20th Century Collection, 343.0122 SNO)

January 2016 marks the centenary of the enactment of the Military Service Act, which introduced conscription for the first time in Britain during World War I. The Act was passed by parliament on 28th January 1916 and came into operation when passed by Royal Proclamation on 10th February 1916. The Act imposed compulsory military conscription on all single men aged between 18 and 41, who were not eligible for exemption.

Unlike other European countries, Britain relied on volunteers to fight during times of war and when Great Britain declared war on Germany on 5th August 1914, this was no different. Many believed hostilities would be over by Christmas. However, it soon became clear that war would not be won in a matter of months. With this realisation, attention rapidly turned to maintaining the war effort and numerous attempts were introduced to encourage voluntary enlisting.

At the outbreak of war, patriotism was high and volunteers rushed to recruiting stations in order to support King and country. A drive to recruit more men was led by Lord Horatio Kitchener (a British military leader who became Secretary of State of War when World War I was declared), for men to voluntarily join up to the army. He is famously depicted in the army recruitment poster, ‘Your Country Needs You’, which was used in a poster campaign to encourage voluntary enlisting. Numbers did increase, however, as the war went on this voluntary system soon proved insufficient as the number of casualties grew. In October 1915, Lord Derby (appointed Director-General of Recruiting by the Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith) introduced the Derby Scheme in order to raise numbers. Under the scheme men aged between 18 and 40 were informed that they could voluntarily enlist or attest with an obligation to be called upon if required. Despite these attempt, by 1916 the British government believed that compulsory active service was the only way to increase the war effort and in turn win the war.

This month’s Treasure is a pamphlet entitled The Military Service Act Fully and Clearly Explained, by Philip Snowden (seen in the image above). The pamphlet was a circular available for the public to buy for one penny in 1916, which clarifies who the Act applies to, persons outside the Act, claiming exemption and outlines the Tribunal procedures (seen in the image below).

Pages 2-3 of The Military Service Act Fully and Clearly Explained, outlining Penalties for Desertion of Aiding Desertion, To Whom the Act Applies and Persons who are Outside the Act, by Philip Snowden (MP), 1916 (20th Century Collection, 343.0122 SNO)

The pamphlet also details the six Grounds of Exemption; men who are better employed in their usual work (such as in food supply or the export trade), work that is more suited elsewhere for the war effort (such as in agriculture or engine drivers), youths being educated or trained, financial and domestic obligations, ill-health or infirmity and the Conscientious Objection. Conscientious Objection is noted to be ‘perhaps the most important of all, and is likely to prove the most difficult in administration’. The Act made limited allowance for men who objected to serve. Conscription was seen as a controversial issue but those who objected to combatant service were known as Conscientious Objectors. They claimed the right to refuse military service on the grounds of freedom, conscience, disability and/or political and religious views and could attest by means of a Tribunal system.

Detailed in the pamphlet on the Tribunal of Conscientious Objectors:

‘Men who apply on this ground should be able to feel that they are being judged by a Tribunal that will deal fairly with their cases.

…If the certificate is granted as a certificate of exemption from “combatant duties” only, then the individual would be liable to serve in certain branches of the Army, as in the Royal Army Medical Corps for instance’.

Page 1 from News Sheet, No. 8, c. 1917 (20th Century Collection, 343.0122 CEN)

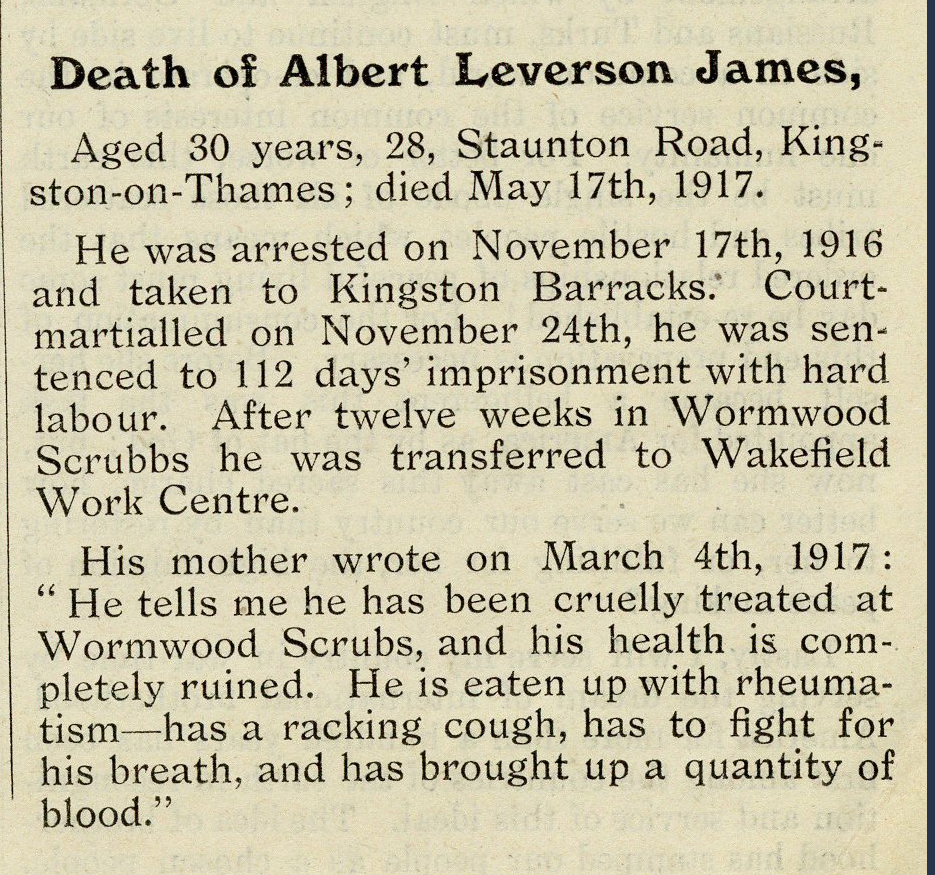

Those who objected to provide their service towards any part of the war effort, whether that be ‘economic, commercial, or other activities’, were sent to prison where the conditions and treatment were harsh. A News Sheet (seen in the image above) issued by The Central News Bureau, c. 1917, includes text on the death of the Conscientious Objector, Albert Leverson James (aged 30 from Kingston-on-Thames). The text explains that Albert was arrested on November 17th 1916, where he later attended a Tribunal and was sent to complete 112 days imprisonment with hard labour. His mother describes his health whilst at Wormwood Scrubs, as ‘…completely ruined. He has to fight for his breath, and has brought up a quantity of blood’ (seen in the image below). After 12 weeks he was transferred to Wakefield Work Centre, where he broke down with haemorrhage double pneumonia and later died on 4th March 1917.

Parliament raised Albert’s death, which was used as an example of the Government’s disregard and mistreatment of men who refused to kill. Albert is commemorated on the Conscientious Objectors’ plaque (1 Peace Passage, London, N7 0BT) along with 69 other Conscientious Objectors who died during World War I.

Death of Albert Leverson James, extract from No. 8. News Sheet, issued by The Central News Bureau, c. 1917 (20th Century Collection, 343.0122 CEN )