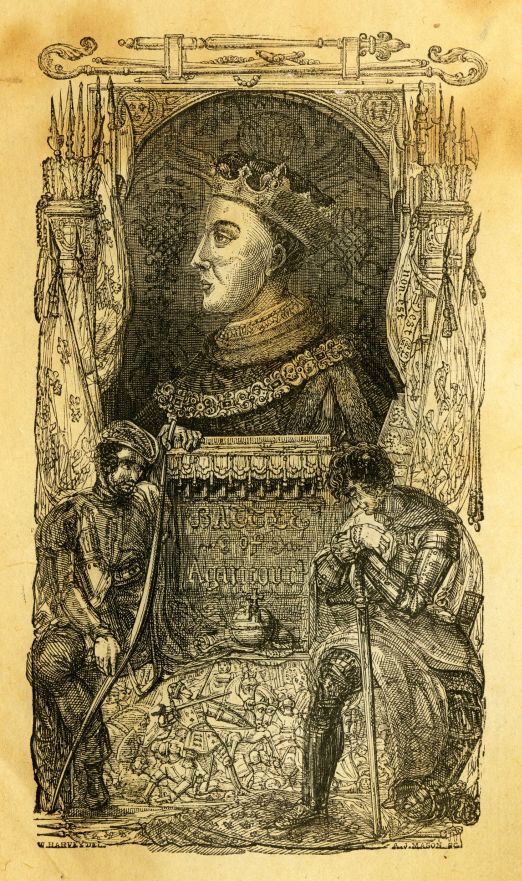

21st March 2013 marks the 600th anniversary of Henry V’s accession to the English throne. Widely considered to have been an excellent King, Henry is renowned for winning the Battle of Agincourt against the French and his immortalisation in Shakespeare’s play of his life.

Henry V, the eldest son of Henry of Bolingbroke and Mary de Bohun, was born in 1387. In 1399 his father deposed Richard II of England and claimed the throne for himself after the King disinherited him. Richard died soon afterwards (he was very probably murdered in captivity) and Henry was created Prince of Wales at his father’s coronation. Henry and his father were of the House of Lancaster and this seizure of the throne was one of the first acts in the Wars of the Roses, which were to continue until 1485.

Henry showed his military abilities as a teenager, commanding his father’s forces in the Battle of Shrewsbury against Harry Hotspur in 1403. He also spent five years fighting against Owen Glendower’s rebellion in Wales. He was keen to have a role in government and ruled effectively as regent for eighteen months from 1410 when his father was ill. However, once recovered, Henry IV dismissed the prince from his council and reversed most of his policies.

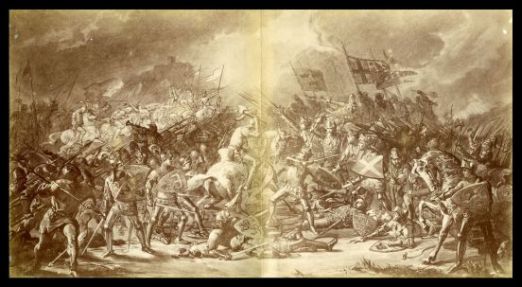

Henry became king in 1413. In 1415,he successfully crushed a conspiracy to put Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, on the throne. Shortly afterwards he sailed for France, which was to be the focus of his attention for the rest of his reign. Henry was determined to regain the lands in France held by his ancestors and laid claim to the French throne. He offered to fight the French Dauphin for the throne in personal combat but was refused. He defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415. The battle was notable for the fact that the English army of no more than 6,000 men defeated the supposedly far superior French army numbering around 20,000.

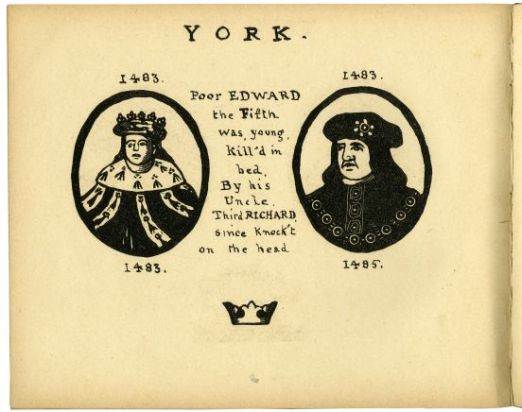

Between 1417 and 1419 Henry followed up this success with the conquest of Normandy. The French were forced to agree to the Treaty of Troyes in May 142. Henry was recognised as heir to the French throne and married Catherine, the daughter of the French king. Unfortunately, Henry died two months too early to be crowned King of France. He died suddenly, probably of dysentery, on 31st August 1422 at the Château de Vincennes. He was only 35 years old. His nine-month-old son, whom he had never met, succeeded him as Henry VI. It was a dangerous period for a child to be King with rival claimants to the throne everywhere. The following 50 years saw the throne change hands several times and Henry VI’s eventual murder in the Tower of London, reputedly by the princes of the House of York.

Henry V’s reputation is one of a chivalrous warrior but he had another side. Described as a man of conviction, Henry was a well-educated and pious man. He was a lover of art and literature and had a particular interest in liturgical music. He gave pensions to well-known composers of his time, and he ordered a hymn of praise to God, which was sung after Agincourt. From 1417, Henry promoted the use of the English language in government, and was the first king to use English in his personal correspondence since the Norman Conquest.

We have William Shakespeare to thank for forming most people’s opinions of Henry. Henry V is one of Shakespeare’s historical plays. It forms the fourth part of a tetralogy dealing with the historical rise of the English royal House of Lancaster. Written in approximately 1599, it tells the story of King Henry V, focusing on events immediately before and after the Battle of Agincourt. Readers have interpreted the play’s attitude to warfare in several different ways. On one hand, it celebrates Henry’s invasion of France, but it also speaks of anti-war sentiment. Henry is portrayed as a hero but he has invaded a non-aggressive country and killed thousands of people. When Shakespeare wrote the play in the late sixteenth century, Henry was considered to be a hero. Henry VIII aspired to be like him and as a Lancastrian he was idolised by the Tudors. He was a warrior King who could not rule today but in his time he restored national pride to England and became a hero the people admired.