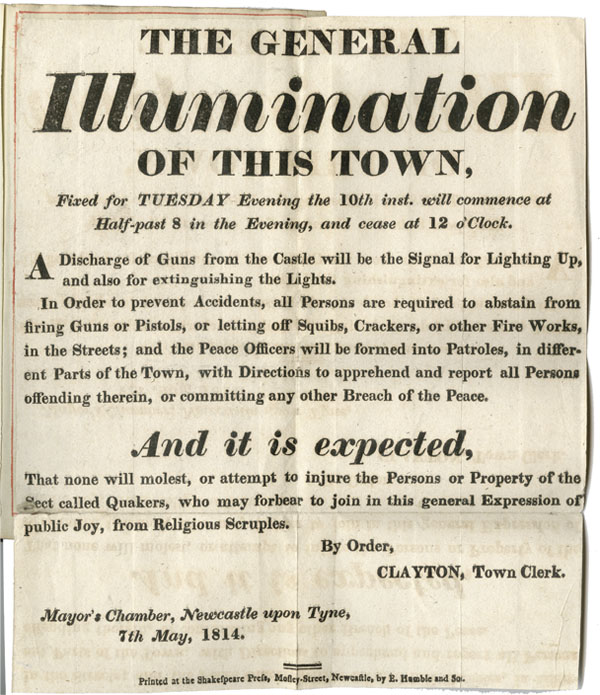

Two hundred years ago this month, on the evening of 10th May 1814, the town of Newcastle was flooded with light in celebration of the defeat and abdication of Napoleon and his exile to Elba, perceived to signal the end of the Napoleonic Wars which had seen the country at war for more than ten years.

This broadside advertised the illumination event. It was seemingly well-organised by town officials who were anxious to preserve the peace and ensure safety, forbidding the letting-off of guns and fireworks and appointing Peace Officers to patrol the streets. Participants were also warned not to harass any Quakers who might abstain from the celebrations on religious grounds, being pacifists.

The event was universally held to be a great success. Local newspapers printed lengthy and effusively-worded accounts. The Newcastle Advertiser said, “At half-past eight o’clock in the evening the signal was given from the castle for lighting up, and, as if by magic, the whole town appeared in a few minutes one blaze of light”. People from all classes of society took part by lighting up their home or premises, “every one striving to excel his neighbour in testifying his joy at the return of peace, after a sanguinary war of unusual duration”.

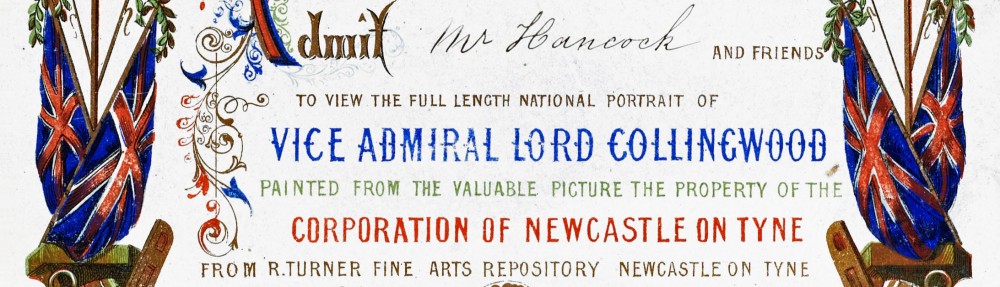

All of the light displays were patriotic and many incorporated transparencies, pictures made from translucent paints on materials like calico, linen or oiled paper and lit from behind with candles.

Highlights included Messrs Farrington of the Bigg-market who filled the arched gateway in front of their warehouse with a large transparency of the Duke of Wellington attired as Mars, presenting Peace to Britannia; and Messrs Brumwell and Dobson, chemists, Sandhill who exhibited a large painting representing the inside of a laboratory and the Devil pounding Bonaparte to powder in a mortar. Mr Waters’ Floor-cloth manufactory was singled out as being especially brilliant, incorporating a giant lit image of an anchor, nearly 40 feet high. The doorway of the Theatre Royal was lavishly lit and occupied by the Newcastle arms with a Latin inscription which in translation means, “May Newcastle flourish into eternity, nourished by abundance and peace”. Also mentioned is a certain Mr Dobson, architect, of Mosley Street who displayed a transparency of Britannia seated, with the British Lion defiantly pacing the shore. Displays such as that at the Dun Cow public house on the Quayside, “a neat, though small transparency, exhibiting the Sailor paid off, and the Soldier returned to this wife and family” hint at the social and economic disruption that the Wars had brought.

It would seem the town officials’ precautionary measures paid off, as the Advertiser reported, “We did not hear of a single disturbance or accident”. According to the Chronicle, the only negative element to the proceedings was “the carelessness and indifference of the coachmen, who were driving the carriages of those who chose to view the exhibition of the evening in that manner; as, by their negligence, were often endangered the lives and limbs of the pedestrians.”

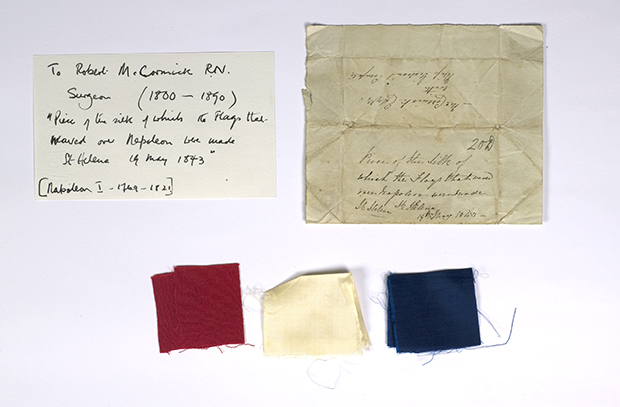

Of course, these celebrations would prove to be a year premature, as ten months later Napoleon escaped from Elba and reassumed power over France until his eventual defeat at Waterloo in June 1815.