(19th Century Collection, 19th C. Coll. 636.22 GAR Elephant folio)

In 1800 fields were ploughed by oxen, tallow production was a major industry (beef fat rendered for use in candles, salves and to lubricate ammunitions), hides were used by the leather industry and the increasing urban population wanted milk and meat for their tables. It was an important time for improving livestock and founding commercially-successful breeds. It was also a time when the tradition for romanticised, stylised portraits of animals and rural life prevailed as owners and breeders commissioned paintings and etchings of the prize animals which were fattened to great weights and toured around the country. Today, those late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century breeds are either extinct or changed beyond recognition, for the most part.

Before the late Eighteenth Century cattle breeds were not formally recognised but intensive selective inbreeding led to distinct breeds and this corresponds with the introduction of illustrated books on animal husbandry. As few farmers would have been literate, animal portraiture served to demonstrate and to advertise the advantages of some breeds over others. However, owners and breeders wanted artists to depict the cattle even more obese than, in reality, they were. Thomas Bewick recalled in his Memoir being sent for to Barmpton to draw cattle and sheep but his drawings were not approved because they did not resemble other paintings of the animals – paintings which did not bear any resemblance to the animals as their corpulence was so exaggerated. Bewick wrote:

“I objected to put lumps of fat here and there where I could not see it, at least not in so exaggerated a way as on the painting before me … Many of the animals were, during this rage for fat cattle, fed up to as great a weight and bulk as it was possible for feeding to make them; but this was not enough; they were to be figured monstrously fat before the owners of them could be pleased”.

Bewick, T. A Memoir of Thomas Bewick

(Newcastle-on-Tyne: Printed by Robert Ward; London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1862), p.184.

George Garrard’s portraits, seen here, were actually drawn to scale. He made plaster models of cattle, sheep and pigs (held in the Natural History Museum, London) and the dimensions of the animals he drew are recorded on the prints.

Short-horned cattle

Short-horned cattle were developed in the late Eighteenth Century when Teeswater and Durham cows were crossbred. Charles and Robert Colling, following Robert Bakewell’s model for breeding long-horn cattle, developed the first systematic short-horn breeding programme and are thus credited as having established the breed. Robert lived in Barmpton, about three miles north of Darlington. (Darlington had gained a reputation for its cattle market or fair.)

According to Garrard’s accompanying text, Juno was Colling’s favourite cow and she had been declared “the best of the year in the district”. She was deep red in colour and had been calved in 1807.

The Holderness breed

Short-horned cattle were developed in the late Eighteenth Century when Teeswater and Durham cows were crossbred. Charles and Robert Colling, following Robert Bakewell’s model for breeding long-horn cattle, developed the first systematic short-horn breeding programme and are thus credited as having established the breed. Robert lived in Barmpton, about three miles north of Darlington (Darlington had gained a reputation for its cattle market or fair).

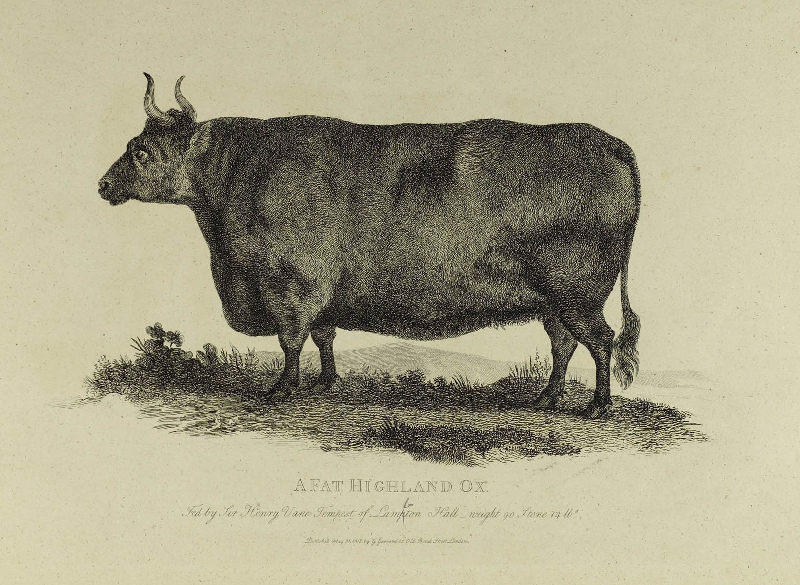

Highland Ox

Sir Henry Vane Tempest (1771-1813) had served as M.P. for Durham City. His Highland ox was black and had been exhibited at Smithfield in 1809, when it weighed 90 stone. Never recovering from the fatigue of travelling, the ox was slaughtered some time thereafter. The ox bears only a slight resemblance to the long-horned, reddish-tan, long-haired Highland cattle of today. Back then, the cattle could be brown, black, red, tan or even brindled (i.e. patterened).

The White Wild Bull of Britain

The open fields, woods and ravines of Chillingham Park, Northumberland (seat of Lord Tankerville until 1971) continue to be home to the wild British cattle. In the early Nineteenth Century, the herd numbered about one hundred – today there are eighty five animals although the harsh winter of 1947 had reduced the herd to thirteen. Garrard relates that “when any of the herd happen to be wounded, or grown old, or otherwise decrepit, the rest run upon it and gore it to death”.

The cattle have lived in Chillingham Park, with minimal human intervention, since the Thirteenth Century and have not been genetically altered. They are small, white with red ears and upright horns.

More about the Oxen

Juno: A beautiful improved short-horned cow bred by Mr. Robert Colling of Barmpton near Darlington – 4 years old.

A Fat Teeswater Ox called The Ox of Houghton Le Spring: An improved short horned of extraordinary size and beauty, bred and fatted by John Nesham Esqr. of that place near Durham – it was got by Mr. Mason’s bull called Trunnell out of a cow by Favourite …

A Fat Highland Ox. Fed by Sir Henry Vane Tempest of Lampton Hall – weight 90 Stone 14lbs.

The White Wild Bull of Britain Bred in its native purity in Chillingham park Northumberland.