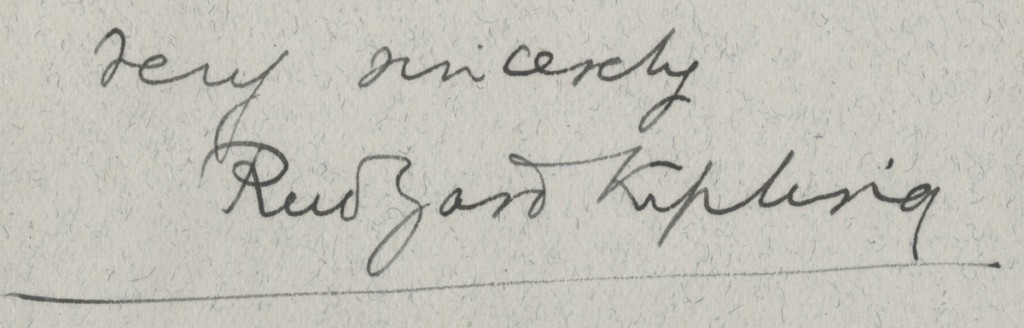

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

150 years ago, on 30th December 1865, Alice and John Lockwood Kipling welcomed their son, Joseph Rudyard, into the world. Rudyard Kipling would go on to become something of a celebrity, with notoriety as a ’poet of empire’. Despite this reputation and his friendships with the likes of Cecil Rhodes and King George V, Kipling declined a knighthood, the Poet Laureateship and the Order of Merit; although he did accept other awards including the Nobel Prize for Literature (1907) and an honorary degree from the University of Durham (1907). After a perforated ulcer took his life on 18th January 1936, he was given a Westminster Abbey funeral – Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was among his pallbearers. He lies in Poets’ Corner.

Kipling’s early years were spent in India – first in Bombay (now called Mumbai) and later in Lahore and Allahabad. (An 11-year interlude in England from the age of five was an unhappy period.) He found work as a journalist and editor, first with the Civil and Military Gazette and then with its sister paper, the Pioneer. Throughout this period, however, he was writing and publishing short stories and poems and his writing reflected the culture, language, sights, sounds and smells of India that he had fallen in love with as a child and was experiencing on adolescent insomnia-fuelled nocturnal walks. His writing was critically well-received and was popular in England.

Hoping to leverage some of his fame, Kipling returned to the UK where he met agent and publisher, Wolcott Balestier. This proved to be a life-changing encounter: Kipling married Balestier’s sister, Caroline (Carrie) in 1892, settled in her native America and had three children with her – Josephine, Elsie and John. Kipling liked to be around children and flourished as a writer of juvenile fiction, enchanting boys and girls with works such as The Jungle Book (1894) and penning parental advice, in verse, to his son in the poem ‘If’ (1895).

‘Rikki Tikki Tavi the mongoose and cobra’ by Charles Maurice Detmold for Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, 1902 (Pollard Collection)

A publically sensationalised quarrel with brother-in-law, Beatty, and the death from pneumonia of Josephine drove Kipling into retreat in England. Again, he focussed on his writing, publishing Just So Stories (1902) in tribute to Josephine. [Newcastle University Special Collections holds the 1955 reprint]

As Kipling withdrew from public view, Europe prepared for war against Germany. Kipling supported the war, perceiving it to be a battle between civilisation and barbarism. He served as a war correspondent from the trenches in France and was keen for his son, John, to see active service, pulling strings to get him enlisted with the Irish Guards. John was killed at the Battle of Loos (September 1915) – he was 18 years old and his body has never been undisputedly identified. Kipling, distraught, turned his attention away from children’s stories and towards involvement with the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission: he helped to create graveyards, advising on the language to be used for the memorial inscriptions; wrote a regimental history of the Irish Guards; and influenced the wording of the letter which would be sent, on the King’s command, from Lord Derby (Secretary of State for War) to mourning relatives. By this time, Kipling’s literary prominence was waning as the world tried to come to terms with the aftermath of the First World War and Kipling with his own grief.

In 2011 the Friends of University Library purchased a significant collection of Kipling’s work in first and early editions; as well as material relating to Kipling, such as ephemera and cuttings which had been brought together by Mr Eric Pollard. The Pollard Collection is accessible via the Library’s online catalogue and the Special Collections team invite as wide an audience as possible to use it. Kipling’s work has been appraised and reappraised over the years and the Pollard Collection demonstrates the breadth of his work.

A Special Collections exhibition will draw upon the collection to remember Kipling in February 2016 – the year that marks the 80th anniversary of his death.