Written by Megan Hardiman, an undergraduate English Literature student.

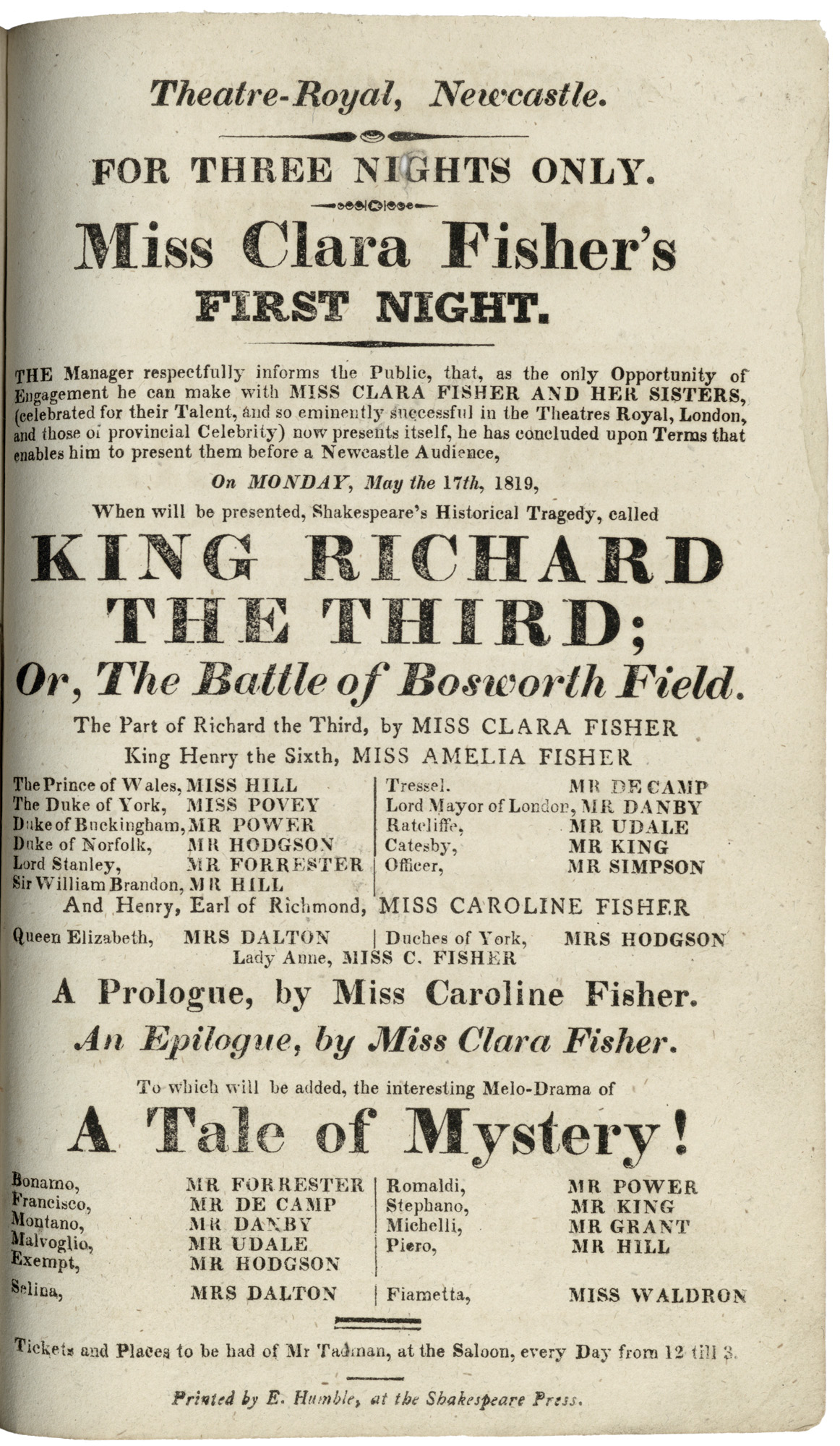

Over the last few months, I have been working within the Special Collections team, focusing on material from the Rare Books collection. Here, I was tasked with collecting metadata for over two hundred playbills that advertised performances from 1819-1820 at the Theatre-Royal, Newcastle. From the Shakespearean classics of ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’ to the forgotten plays of ‘Bamfylde Moore Carew’, each playbill offered a unique window into Newcastle’s theatre scene.

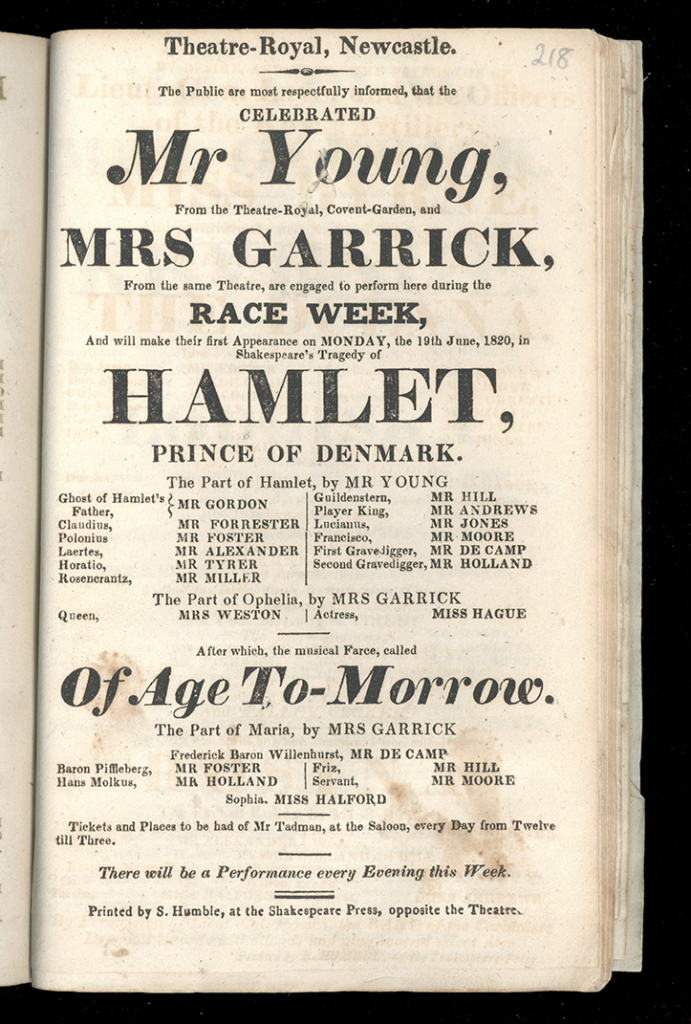

As a third year English Literature student, I am admittedly an avid theatregoer, and often find myself at Northern Stage or Alphabetti Theatre indulging in upcoming and new material, so to see experimental plays were the heart and soul of the theatre in the 1820s was a pleasant surprise. However, the very nature of the plays has changed significantly, with titles such as “Of Age Tomorrow” and “The Day After the Wedding; Or, a Wife’s First Lesson” seldom featured in contemporary theatre. After reviewing the collection, there were thirty-four different titles that had negative gendered connotations, with some performances featured several times throughout the recorded year. The attached playbill illustrates the relationship between male and female performing bodies. Both Mr Young and Mrs Garrick are advertised as featured actors from London, yet Mr Young plays Hamlet, the fallen hero in Shakespeare’s tragedy, whereas Mrs Garrick is cast as Ophelia, who is driven to suicide as a consequence of Hamlet’s control, and Maria, the principal female role in ‘Of Age To-Morrow’. The playbill, like a time-traveling portal, allowed me to witness the disparity in roles assigned to male and female actors. While Mr. Young graced the tragic heights of fallen heroes, Mrs. Garrick drew the short end of the stick, predominantly featuring in what was deemed a musical farce.

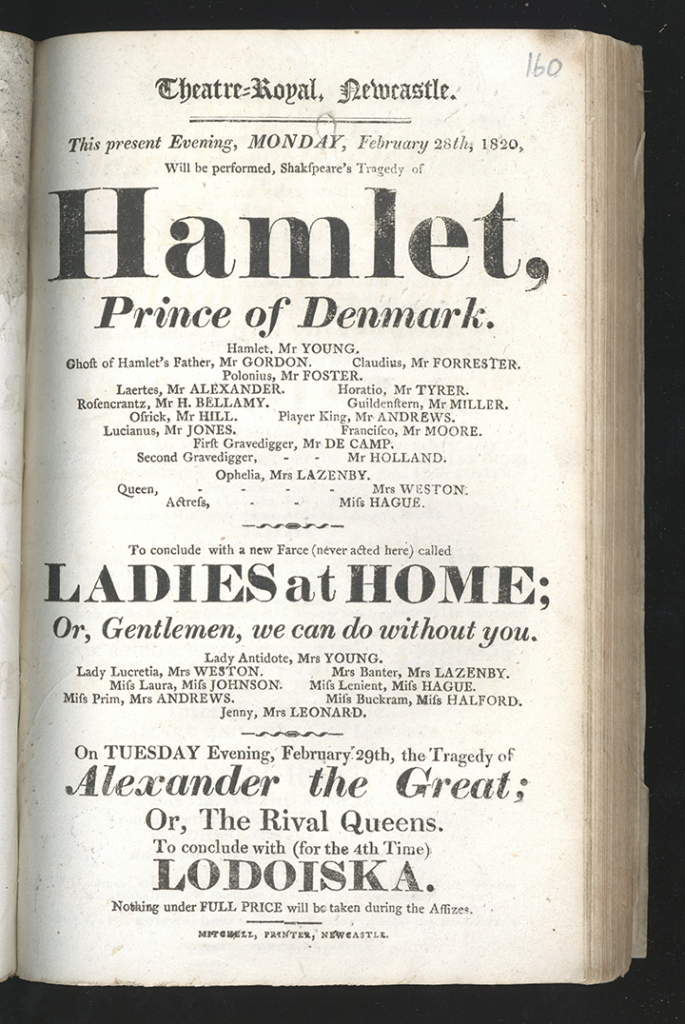

Shakespeare’s tragedy ‘Hamlet’ was also paired with ‘Ladies at Home; Or, Gentlemen, we can do without you’. This disparate pairing seemed strange at first, and I spent a while scratching my head as to why the company would have done this. After some deliberation, I came to the assumption that it was an opportune moment to trial the new experimental play and measure its success with a large audience. ‘Hamlet’ generally attracted a bigger reception due to its popularity, and this is evident through the notice at the bottom of the item stating, “Nothing under FULL PRICE will be taken”, which suggests that a sell-out audience was likely. This then gave way for the Farce “Ladies at Home” to be aired. Perhaps this was revolutionary, or simply a marketing technique to test the waters of a female cast, but either way the playbills have given scope for a gendered analysis.

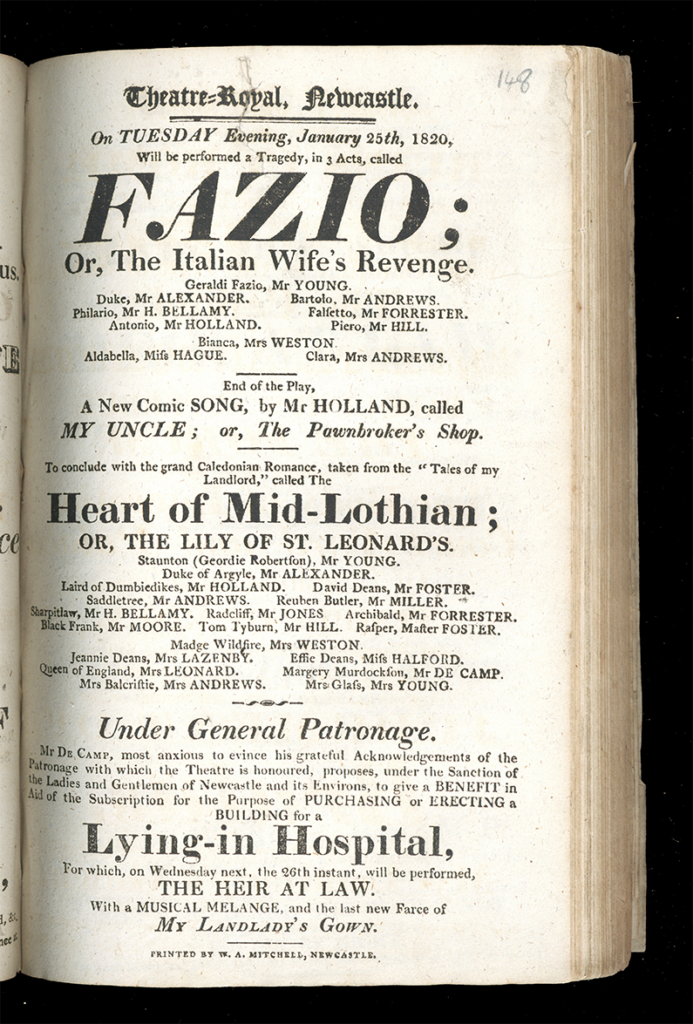

The relationship between the Theatre Royal and gender has inspired me to write a dissertation on the lying-in hospitals around Newcastle, by using the playbills as a portal into the comparative analysis of the presentation of performing female bodies and pregnant women. As seen in the playbill, there were benefit performances for the building of a lying-in hospital, that was completed in 1826 and built opposite the city library. As such, the playbill has become a window into the gendered expectations imposed on both actors and women during the nineteenth century, and I will use the research gathered in Special Collections to inform my third-year dissertation.