As a means of spreading information quickly and cheaply among working class and increasingly literate populations, printed ephemera was both a forerunner and supplement to early newspapers. The activity of using local printers to convey a message, including advertising goods and services, local events, and public notices peaked in the 19th Century. These were never meant to become historical artefacts, rather to be passed around, stuffed in pockets, pasted to walls and read out loud to communicate an idea at the time then be thrown away or often reused to wrap meat, cakes and soap. Because of this, where they have survived surreptitiously, such material gives us a useful insight into societies at the time and are a useful research resource.

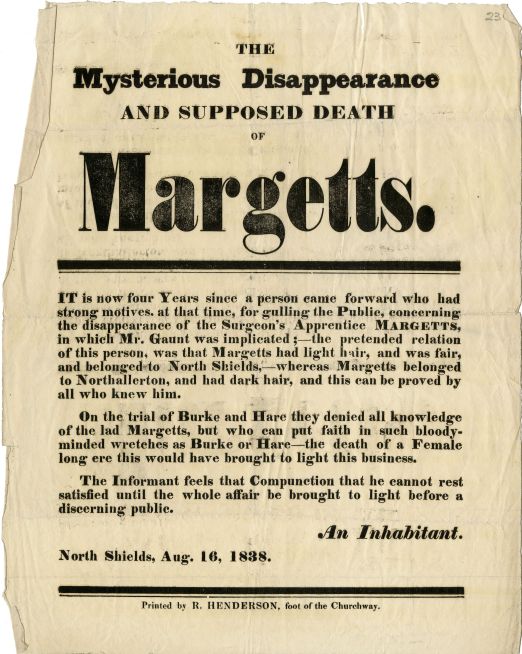

A prevalent use for this type of ephemera was as crime notices; alerting people to misdemeanours and often offering rewards for information. The broadsides featured here, which were essentially posters that would have been displayed in prominent public places, concern the mysterious disappearance of a local surgeon’s apprentice John Margetts.

The broadside titled ‘The Mysterious Disappearance and supposed death of Margetts’ (above) implicates a Mr Gaunt in “gulling the public” over his disappearance. It also suggests that infamous murderers William Burke and William Hare, who from 1827 to 1828 killed 17 people in Edinburgh and sold the corpses to a private anatomy lecturer for dissection, were questioned in connection with his disappearance but denied all knowledge. The anonymous writer does not seem to fully believe this, asking “…who can put faith in such bloody-minded wretches…”.

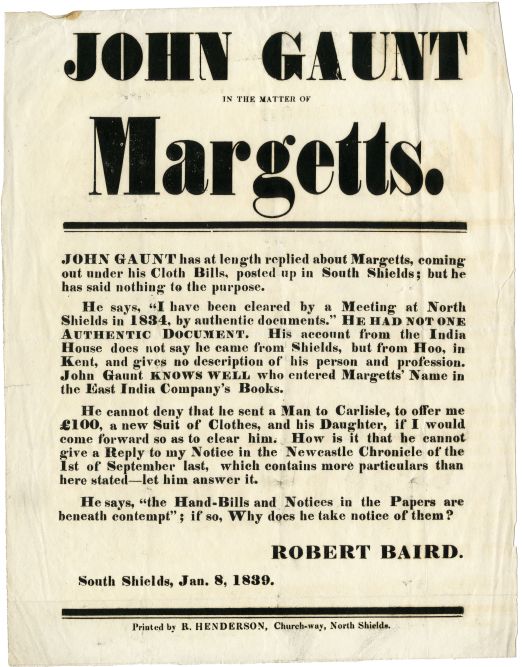

In broadside titled ‘John Gaunt in the matter of Margetts’ (below), writer Robert Baird is much more resolute in his belief that John Gaunt is behind Margetts’ disappearance and deeply sceptical of a separate broadside “posted up in South Shields” by Gaunt, seeking to exonerate himself.

He alleges Gaunt’s claim that Margetts left to enter the service of the East India Company, based on an entry in their books, is false as it is not the same John Margetts, or may even be a forgery by Gaunt himself.

Particularly damning is the claim that Gaunt offered Baird “£100, a new Suit of Clothes, and his Daughter” to keep quiet!

Further research from contemporary copies of newspapers (available to Newcastle students through the 19th Century British Library Newspapers) sheds a little more light on the mystery.

Amid the claims and counter claims, we learn from these sources that two gentlemen from Newcastle petitioned the Scottish courts for the re-apprehension of William Hare, who turned King’s evidence against his accomplice to be spared execution, because they suspected Margetts of being the unidentified “Englishman murdered by Burke and Hare” (The Glasgow Herald, Feb. 16, 1829).

The reason behind Robert Baird’s suspicions also become clear as Margetts was last seen on the 22nd February 1827 after being sent with some medicine for John Gaunt’s wife. Seemingly dogged by rumours he was involved, John Gaunt successfully won 5 pounds and 20 shillings “compensation for certain slanderous words… reflecting on his character” (The Newcastle Courant, 1st March 1834), at the Newcastle Spring Assizes court after two individuals accused him in the pub, due to his extravagant lifestyle, of getting his living “by other means”; namely the ‘burking’ of Margetts. The term was derived from the aforementioned William Burke, and meant to smother and compress the chest of a victim in order to sell the corpse to medical schools. This was particularly profitable before the Anatomy Act of 1832, as doctors could then only lawfully use the corpses of executed criminals to teach their students. As the demand outstripped the supply, grave robbers or worse made a roaring trade!

Despite John Margetts Snr. placing reward notices for information in the Newcastle Courant on 3rd May 1828 and again as late as 7th December 1839, it seems the true fate of his son remains lost to history. Although it is little solace to poor Margetts, however, these examples of printed ephemera show how crime and punishment was viewed and enforced at street level through a shared morality and sense of justice… or just as a means of spreading malicious gossip!

Can you shed any more light on the Mystery of Margetts?