This post originally appeared on 2 November in the excellent global health blog Policies for Equitable Access to Health; it is reproduced here by permission, with minor edits. All views expressed here are exclusively those of the author. Others quoted here do not necessarily agree with them.

Whistling past the graveyard is a long-ago expression that describes the behaviour of people who are afraid of ghosts, but like to pretend that they are not. So, they whistle as a show of nonchalance while walking past graveyards late at night. The expression well describes the current behaviour of academics and apparatchiks alike, in much of the world, as they respond to the coronavirus pandemic. The malevolent spirits that they try to ignore are long-term economic and health implosion and possible state collapse. No one really wants to admit how bad things could get, and how long the damage could persist. On the part of political classes and oligarchs, such behaviour is perhaps understandable; they want to risk neither riots nor collapsing financial markets. On the part of academics who should stand up for serious scholarship, it is inexcusable.

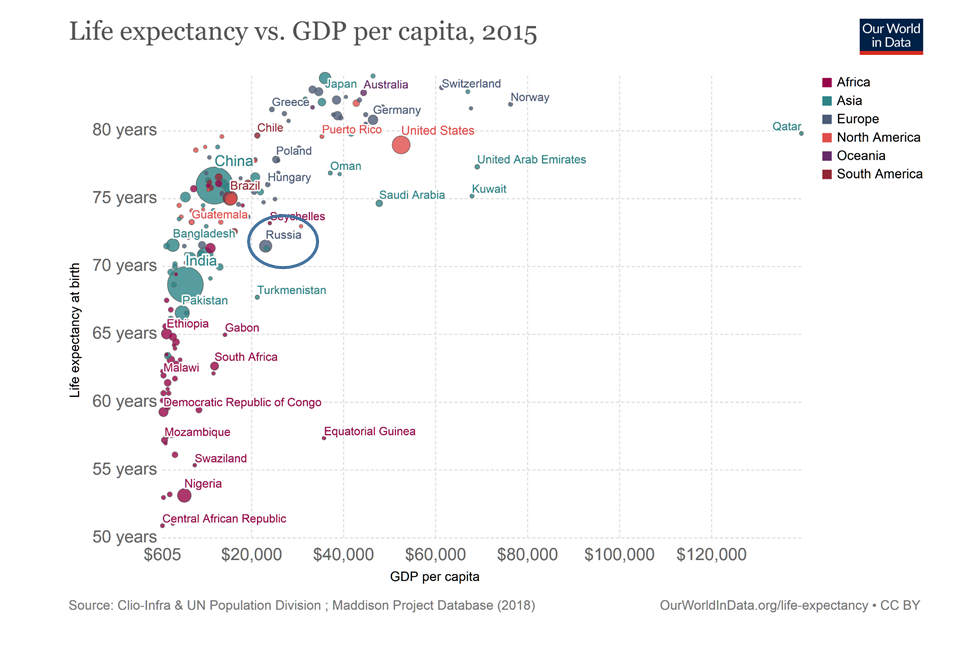

In June 2020 – how long ago that now seems! – I argued in a webinar that the best available model for understanding the probable long-term consequences of the pandemic is the experience of post-Soviet Russia, where over a period of a few years the economy shrank by about 50 percent; social provision mechanisms and large portions of the health care system crumbled; and life expectancy plunged by several years. Subsequent economic recovery was accompanied by drastic increases in inequality and massive capital flight, so that half of all Russians’ financial wealth is now held offshore, and the emergence of a new stratum of politically connected billionaire oligarchs. They now own, among much else, substantial chunks of London. The leading authority on the post-Soviet mortality crisis and colleagues have pointed out that a quarter-century later, Russian life expectancy still did not reflect the country’s economic recovery. In other words, it was several years lower than would be expected given its GDP per capita – years lower than in (for example) slightly poorer Brazil, Chile and China. Back to this model later.

The UK has been an especially disturbing case thanks to the fecklessness, despotic inclinations and corruption of Prime Minister Johnson’s Conservative government. These have been ably described by George Monbiot, whose commentaries are essential reading. The most disturbing aspect of events over the past few weeks, in Europe in the first instance but not only there, is the demonstration they have provided of just how widespread the evisceration of basic public health capabilities has become. It helps to understand this process by way of a political science construct known as the Overton window – an idea emanating from a right-wing think tank that was concerned, in the first instance, with ways to soften public opposition to privatising education. The window frames the universe of public policies that are considered at least plausible, rather than beyond the pale. ‘Shifting the window’ means that, over time, policies that once were well outside the mainstream, on either end of the left-right political spectrum, come to be considered plausible and, eventually, just common sense.

President Trump’s destruction of a range of political norms is one illustration of shifting the window. Over the longer term, decades of well-funded neoliberal efforts to shift the Overton window rightward, the trajectory of which is clear for those willing to do the necessary reading, have led to a situation in which maintaining basic public health infrastructure needed for pandemic preparedness came to seem like an extravagance, an unnecessary expenditure on a too-large state, despite authoritative warnings about the economic and public health importance of that infrastructure. In much of the world, Covid-19 must therefore be understood as a neoliberal epidemic – a phrase my colleague Clare Bambra and I coined in 2015. As another colleague, public health physician Allyson Pollock, has put it, austerity in the UK has led to a situation in which ‘[n]ational and local expertise has been lost and many of [her] colleagues in communicable disease control were made redundant.’

The unwisdom of such abandonment of precaution was articulated in 2015, on a small scale, by 267 economists led by Lawrence Summers – Lawrence Summers, of all people – writing about the benefits of universal health coverage: ‘The debilitating effect of Ebola could have been mitigated by building up public health systems in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone at one-third of the cost of the Ebola response so far.’ If there really were such a thing as the international community, it might usefully reflect on how much it would have been worth investing in measures that could have mitigated a pandemic now anticipated to result in the loss of more than US $12 trillion in economic output in 2020 and 2021 alone, according to the International Monetary Fund.

According to projections from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at this writing (30 October, 2020), on current trends the virus will have killed approximately 2.5 million people as of 1 February 2021, with a wide variation in outcomes possible depending on what precautions are taken, and where. This projection deals only with the short term, and cannot address the longer term health consequences of the pandemic, for at least two reasons.

First, it does not include deaths attributable to reduced access to treatment or prevention for other conditions among people not infected by the virus. In the UK alone, a former Conservative health secretary is warning of ‘tens of thousands of avoidable deaths within a year.’ Second, it does not and cannot anticipate health impacts of the economic depression and ratcheting-up of inequality that will follow the locking down of major segments of entire economies and societies. Unfortunately, and despite everything we know about the social determinants of health and health inequalities, in much of the academic world arguing for consideration of these health impacts is immediately equated with callous indifference to human life. This should not be the case.

This is why I am more convinced than ever of the distinctive relevance of the Russian experience. As the UK enters another nationwide lockdown, with an economic cataclysm that will be life-threatening for some certain to follow, all that will remain of some local and regional economies, and millions of individual futures, is wreckage. Much the same can be said for many other jurisdictions. It is possible, of course, that an effective vaccine will be developed and rolled out sooner rather than later, avoiding some of the more disastrous scenarios. But there is no vaccine for the inequalities that were already devastating lives before the pandemic. As just one illustration, in 2011 – at just the start of the UK’s decade of viciously disequalising Conservative austerity – the ‘Great British Class Survey’ found that one-third of British households, supported by low-wage or precarious employment, had an average of just under £1,000 in savings.

Even in the best possible post-pandemic world, inequalities that have been further magnified will be remediable only through huge programmes of public investment and direct redistribution, realistically financed by way of long-term borrowing at current low interest rates and progressive income, wealth and land value taxes. Such policies, for the moment, remain well outside the Overton window anywhere I know of, despite important advocacy by agencies like the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. In a world of increasingly ungovernable private wealth and the opportunities for capital flight and tax avoidance offered by a borderless financial world, it is far from clear that most governments even have the political capacity to undertake them. Many dreams of the young and the old alike will be consigned to the graveyard referred to in my title. Truth-telling on this point is long overdue.