Acknowledgement: This commentary was originally written for Policies for Equitable Action on Health. It reposted here with some additional material with the kind permission of Daniele Dionisio, who runs PEAH. Further republication consistent with the Creative Commons licence that applies to my entire blog is encouraged.

Introduction: The pandemic and the perils of averages

Figure 1. Downtown Montréal, March 2023. Photo: T. Schrecker

I wrote part of this post during my first post-pandemic visit to Montréal, a Canadian city that I love and once called home. It has not been easy. While many affluent parts of the city have largely regained their pre-lockdown vibrancy, other districts are now populated mainly by vacant shop fronts (Figure 1). At the same time, sometimes almost next door, numerous glittering condo towers soaring as high as 61 storeys are under construction (Figure 2). They are beyond the financial reach of most of the city’s residents, trapped like other Canadian city dwellers in a deepening crisis of housing affordability, which is part of a more general and widespread cost-of-living crunch.

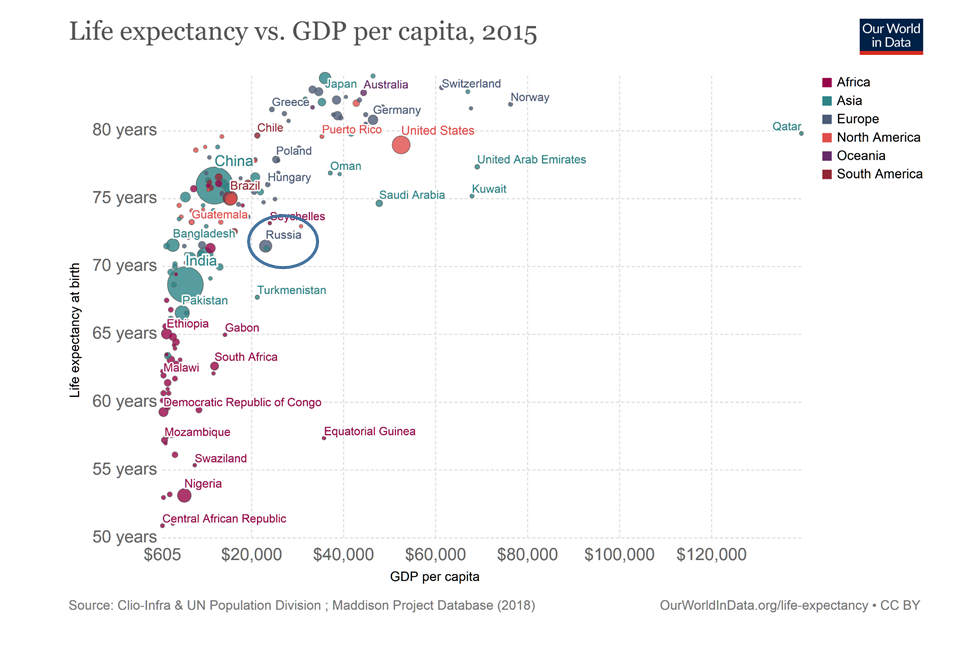

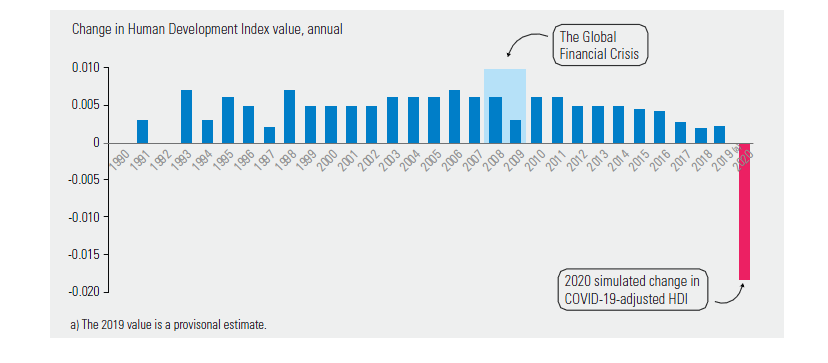

Policy analysts are lauding governments – and some governments are congratulating themselves – for having sidestepped the cataclysmic lockdown-induced recession that it was reasonable to anticipate (as I did) in the first months of the pandemic. In both the United States and Canada, temporary responses to the pandemic reduced officially defined poverty rates to a degree that would have been highly improbable under less extreme circumstances. The US Federal Reserve’s annual survey of households in 2021 found the highest levels of several indicators of financial well-being since the survey began in 2013. On the other hand, in the United Kingdom child poverty (and therefore family poverty) has continued to increase and deepen through the years of pre-pandemic austerity and since then.

Figure 2. Downtown Montréal, March 2023. Photo: T. Schrecker

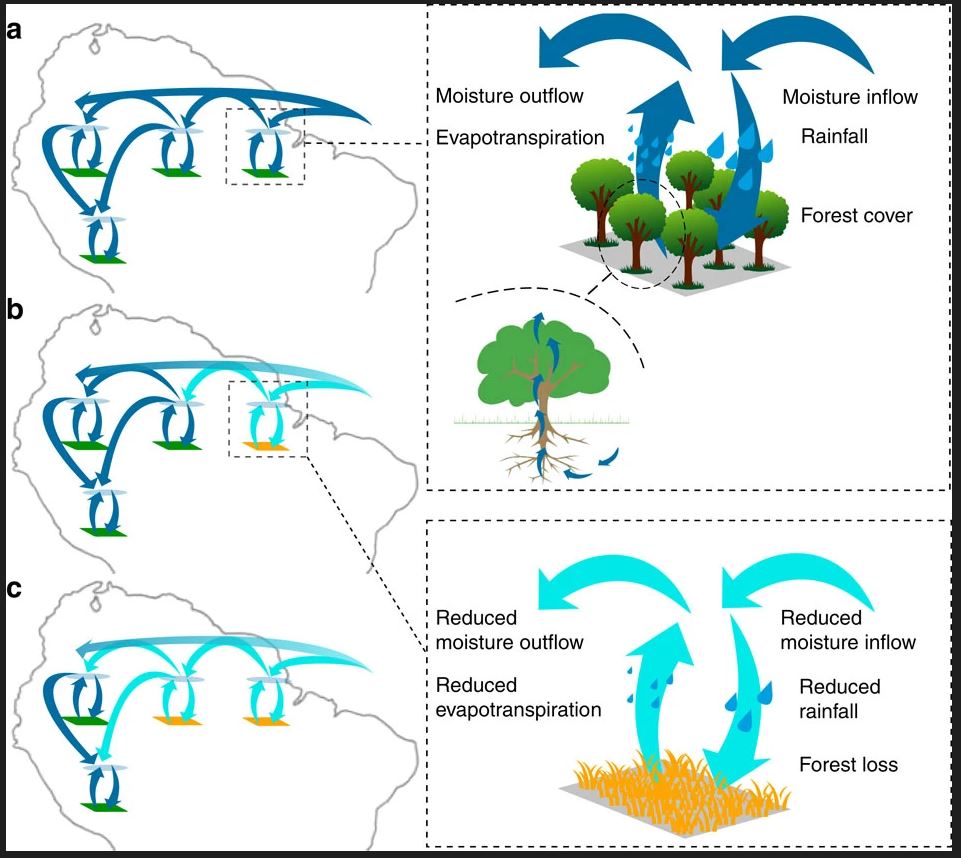

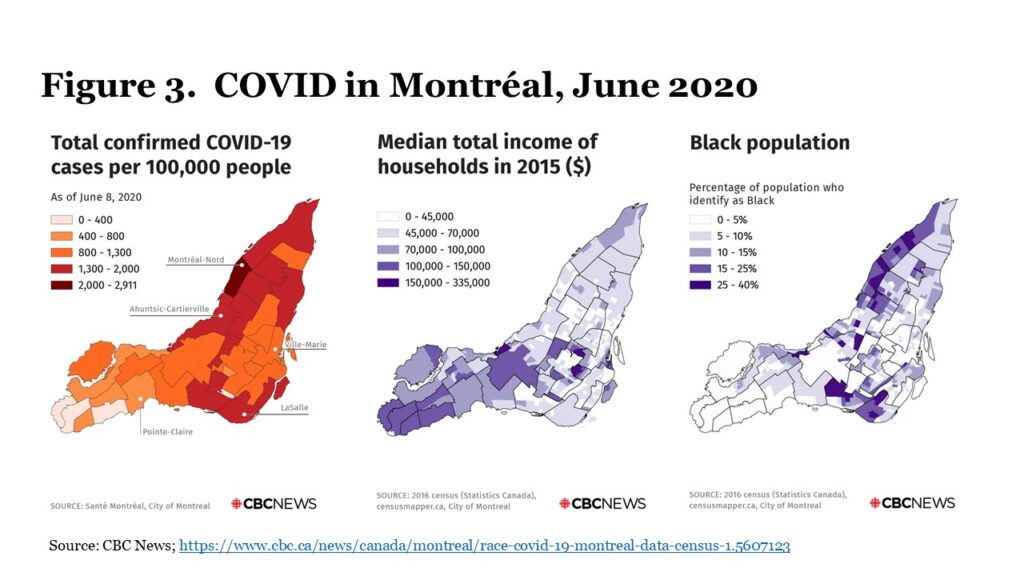

As this observation suggests, whatever the view from 30,000 feet, ‘on the ground’ the consequences of the pandemic can look very different. Very early on, data from Montréal made it clear that the impacts of the pandemic were stratified by class and race (Figure 3). Cities like Montréal may ‘recover,’ in a statistical sense, but many of the businesses that thrived there and the households that lived there are not likely to do so. There is an important methodological point here. As in any other inquiry related to the social determinants of population health, averages can be fatally misleading. Eduardo Galeano wrote: “Where do people earn the Per Capita Income? More than one poor starving soul would like to know.” Aggregates and averages cannot tell the story of life in a city where buyers of million-dollar condos move in, as tenants dispossessed by a wave of ‘renovictions’ move out. Here is yet another illustration of why the tipping point concept is important. Before the pandemic, researchers were writing about gentrification and “condoization” in Montréal. The pandemic and policy responses to it have accelerated the processes, and as elsewhere magnified the impacts on inequality. These are likely to be intractable and intergenerational.

The return to business as usual

The pandemic transiently made radical expansion of the realm of the possible in economic and social policy seem plausible. While rhetoric about “building back better” proliferated, two detailed and thoughtful proposals in this vein actually appeared in 2019. The annual Trade and Development Report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) called for a global Green New Deal organized around raising labour’s share of incomes worldwide, raising additional revenue to support fiscal stimuli, and expanding public investment in clean transport and energy systems and sustainable food production. Also in that year, British historian Simon Szreter and colleagues published a prize-winning UK-focused proposal for “incentivizing an ethical economics” organized around raising taxes to invest in sustainable growth and offering universal care provision in old age – a “new social contract” and “new intergenerational contract”.

Taking seriously building back better means, in the words of iconoclastic economist Mariana Mazzucato, “we need to radically reform and rearm the state.” It is not as if the necessary policy instruments are unavailable, be they the public development banks to which UNCTAD devoted an entire chapter of its 2019 report; the range of measures described by Szreter and colleagues; or – to use an example from close to home – the housing co-operatives that provided affordable housing to many Canadians before senior levels of government abandoned the housing sector to market forces. Especially in an age of long-term geopolitical instability, calling for more rather than less spending on defence, using those instruments to ensure that “the costs and benefits of a green transition are distributed equitably across society so that social injustices are tackled alongside environmental crises” (to quote Mazzucato again) will require substantial new revenue streams mobilized through progressive taxation.

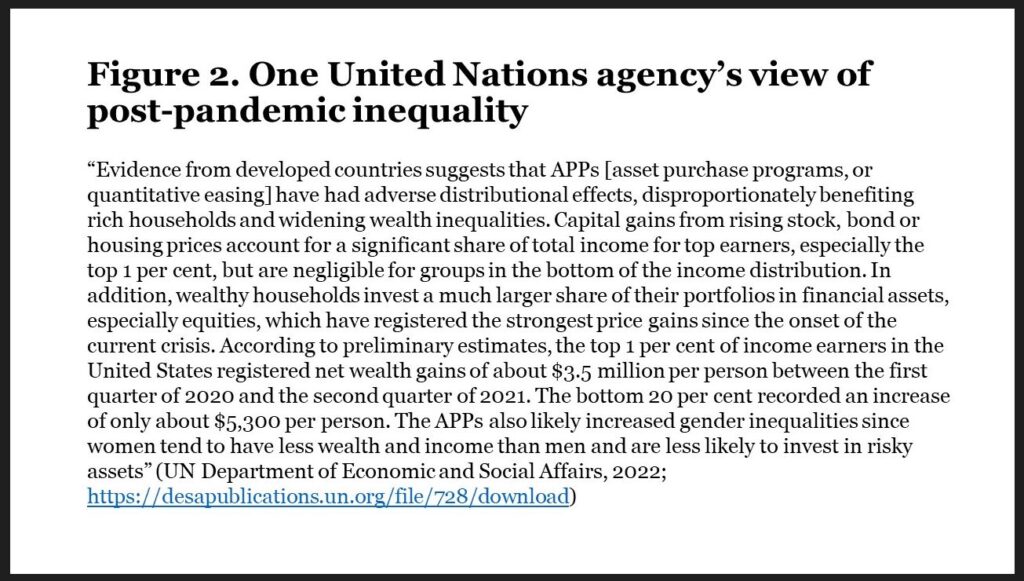

Both UNCTAD and Szreter and colleagues emphasized the importance of this point, as did later analyses. In 2020, as the scale of the pandemic’s impacts was already becoming clear, UNCTAD argued that “[in] light of the further increase in inequality resulting from this crisis the case for a wealth tax seems irrefutable.” Even the Financial Times’ editors conceded that wealth taxes would “have to be in the [policy] mix” (paywalled). Since then, policy silence on this point has usually been deafening. US president Biden’s March, 2022 legislative proposal to levy a minimum tax on the ultra-rich and to tax unrealized capital gains on financial assets was a striking outlier, although the perverse structure of Senate representation doomed it from the outset. Improbably, the UK’s Conservative government in November, 2022 introduced incremental tax changes that slightly reduced the preferences granted to the ultra-rich and lowered the level at which the highest marginal income tax rate applies, but will do nothing to reverse the magnification of inequality and hardship during the pandemic. More conspicuously than in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 financial crisis, innovation has been abandoned and policy – in particular, commitment to reducing inequality – reset to business as usual in a wave of what the Roosevelt Institute in the US has called zombie neoliberalism.

The reset is perhaps not surprising given the outsized and growing influence of money in politics, as described by Brooke Harrington, Jane Mayer, and Peter Geoghegan among many others. Catherine Belton has focused on how Russian flight capital influenced British politics as it penetrated London property and financial markets, and in an important comparative study US political scientist Larry Bartels found “remarkably strong and consistent evidence of substantial disparities in responsiveness to the preferences of affluent and poor people. Insofar as policy-makers respond to public preferences, they seem to respond primarily or even entirely to the preferences of affluent people.” This dynamic is likely to be more powerful than ever in a more unequal post-pandemic world where resistance emanates not only from transnational corporate tax avoiders and the one percent with their hypermobile assets, but also a substantial stratum of newly enriched property owners with an expanded stake in financialized housing markets.

It is therefore dispiriting but arguably predictable that (for example) Britain’s opposition Labour Party has recently tried to lower expectations of future change, its leader “constantly calculating which of the people desperately awaiting his government he can afford to ignore because they have no powerful advocates” in the words of eloquent Guardian columnist Nesrine Malik. The answer, probably, is most of them. One must hope that such efforts fail, yet at the same time contemplate with unease the politics of desperation that the future is likely to bring.