February 2023

“We—all of us on Terra—live in disturbing times, mixed-up times, troubling and turbid times. The task is to become capable, with each other in all of our bumptious kinds, of response” – D. Haraway (2016, 1)

Thinking with Soil

The weather was biting cold today at Windmill Hills, but we trooped out to the garden and began work on reactivating the compost heap. This sits behind the polytunnel in a large wooden box, divided into three parts. There are four of us to begin with and more join in later. We are all swaddled in winter coats, sporting wellies and gloves. Cal, the horticulturalist and head gardener at The Comfrey Project, gave us instructions on how to categorise the different organic matter. We place thick, woody materials in one pile, seedlings and looser, more flimsy matter in another, and stalky palm materials in another. We remove any couch grass we find as its rhizomatic structures means it can seed in the heap and regenerate. Resilience 101. The pile had gone cold and the system needed rebalancing so as to get the composting action started again.

Cal talks to us about aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. How the soil is alive and how the matter we put in our compost heap encourages these different kinds of bacteria. A compost heap can stink to high heaven if there is too much ‘green’ matter (your kitchen scraps and soft, mulchy waste). The trick (and the skill) is to try and get the balance between green and brown (the woodier kind of matter). Our piles are the first step in this process.

We get on with cutting the longer stalks and branches into smaller twigs. The smaller the better. Mine and T’s hands begin to ache from the repetitive action of the secateurs. Cal sharpens them for us and the action becomes easier. Z and A are at work sifting the bottom of the old heap for any useful compost. They use old veggie boxes to sieve the matter through. We come across ‘secondary decomposers’— pink earth worms, unused to daylight, wood louse and spiders. I remember the brown mouse I startled while turning my compost box last winter. He is a ‘tertiary decomposer’ I am told. I felt very sorry to have disturbed his sleep. My own composting had been unscientific, undisciplined and, stinky. Now I learn that cultivating aerobic bacteria is key; these life forms are the primary decomposers. They’re the gold of the soil and their work brings dead matter back to life.

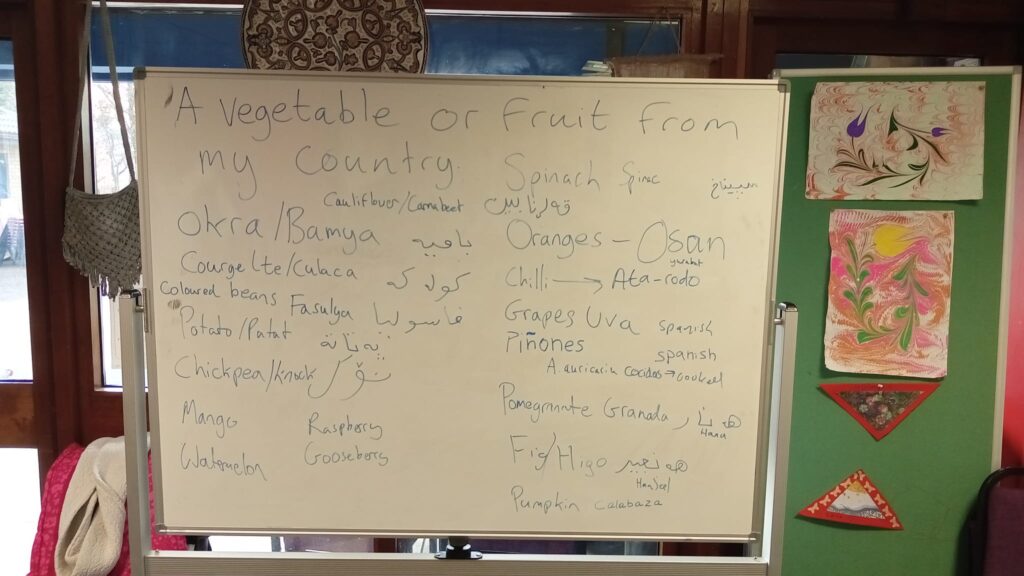

When we are called for lunch, we gather inside. S has prepared some spicy pasta and this is just what we need to warm us from the inside out. We sit around the table and the volunteers discuss what vegetables from their home countries they’d like to see growing in the garden this year. Chickpeas, Avocados, Spinach, Lemons, Okra… some of these are doable. Others not likely given the climate in the North East and despite the magic microclimates of the polytunnel. It is hard to imagine eating okra from the garden as it is today, all bracing wind and bare beds. But the seeds are lady’s fingers in waiting, the taste coded in, immanence if ever it was. The soil is warming up with each week. The compost heap will heat up soon. The sun will heat the polytunnel and it will become balmy inside, beneath the cardboard sheaths covering the earth, the bacteria are feasting away and preparing the ground for this year’s seedlings. There is so much happening in what we call ‘waiting’ or ‘interim’. So much activity and energy that we don’t always think about when we pick the vegetables off the shelf in our supermarkets.

I am looking at soil differently. Realising that words like ‘dirt’ and ‘brownfield’ are not only inaccurate, but political. Thinking with soil involves recognising all the life, all the teeming critters, visible and invisible, that make the ground grow. Thinking with soil means reframing labels like ‘brownfield’, and understanding how such a label works to make invisible this life, and its significance to all other life. The question emerging for the research project now is: How to rethink the city with soil in mind?