In 1968, as Paris reeled from the greatest national strike in its history and barricades still lined the streets, a group of radicalised art students travelled to London to meet with eclectic independent publisher Dennis Dobson.

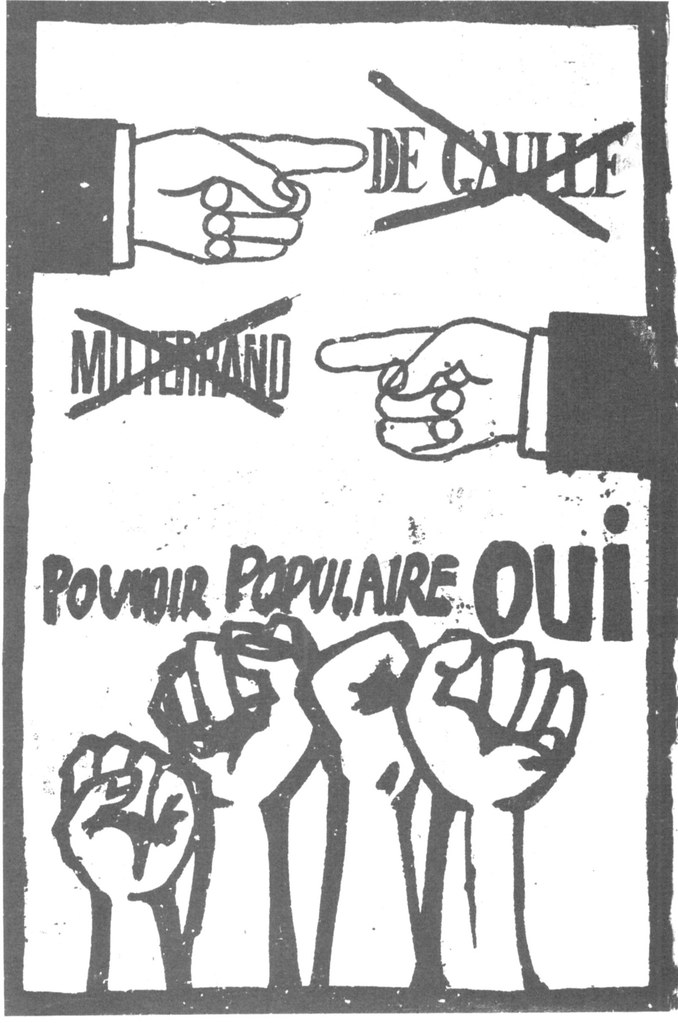

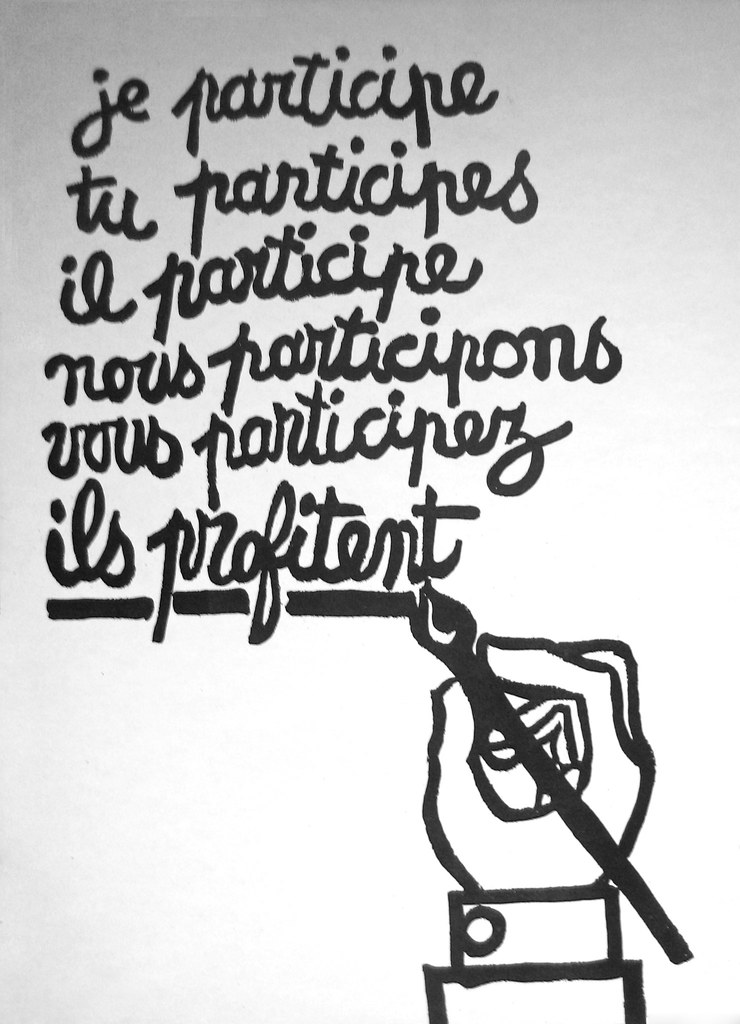

The students were members of the Atelier Populaire, a political art collective whose posters would give May ’68 its visual language and who would go on to become one of the most influential movements ever to produce agitprop posters. Their pared back visual and linguistic aesthetic mean that their work resonates forcefully with anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and resistive movements of the twenty-first century.

This is a small side project that came about as part of BBC programme ‘Inside Out: North East and Cumbria’. The BBC team were making a programme on Brancepeth Castle‘s link to publisher Dennis Dobson. Dobson worked alongside the agitprop poster collective, the Atelier Populaire, to publish in book form their posters which had lined the walls of streets and factories across Paris over the heady revolutionary days of summer ’68.

So, who were the Atelier Populaire, how have they influenced agit-prop and street art, and how did the posters from one of the most radical political art movements of the twentieth century end up in a damp castle in County Durham?

The Atelier Populaire, or, the disappearance of art

Originating with students who had occupied their elite school, the École des Beaux Arts, at the height of the ‘events’ in mid-May ’68, the Atelier Populaire’s name already gives an indication as to the values of the collective. These values consisted in seeing art as a social tool, a weapon in the fight against a repressive established order, and a means to forge bonds of solidarity between the students’ and the workers’ respective causes. Shifting the signifier from ‘Ecole’ to ‘Atelier’, marked their symbolic refusal of art’s ‘bourgeois’ status, and testified to the Atelier Populaire’s attempt to reformulate art’s spatial and social identity. The gallery’s white walls were swapped for the walls of the streets and factories, the aura and value attached to the artist’s signature was eviscerated through anonymity. Collective decision-making as regards the themes and selection of the posters to be printed placed the message and its political necessity before copyright. Similarly, the term ‘populaire’ emphasised their affinity with the struggles of immigrants, the working classes and their sympathies with anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and anti-Gaullist ideas. The name alone then weaves conceptual threads linking the group to French Revolutionary ideologies of ‘le peuple’, and the righteous romanticism inherent in revolutionary mythologies that placed the ‘people’ at the heart of the nation.

In a sense then, the Atelier Populaire willed something like the disappearance of Art—‘Art’ as it was understood by the mid-century establishment. Liberating it from the white cube and placing it in the service of popular political action. The manifesto of the opening pages of the book published by Dennis Dobson, states that art is now a tool in the arsenal of popular struggle against repression. More than this, the Atelier Populaire demonstrated a hyper-awareness of the tendency for capitalism to absorb the figures of its refusal, and to reproduce its assailants as commodities. In their manifesto, the Atelier Populaire expressly stated that their posters should not be read by ‘experts’ for their aesthetic or historical significance—these being the narratives of the ruling classes. Rather, they wished for this material to persist in its resistive visual activity, to promote, provoke and support political action on the part of everyday men and women.

Why the Riot?

The events of May 1968, commonly labelled student revolts, were actually far more than the concern of a few hundred radical students. By the end of May over 9 million people were out on strike across France, de Gaulle was preparing for a potential coup d’état, two people had been killed during police repression of street demonstrations, and the country was at a standstill. No TV, no mail, no transport, the government in crisis, and industrial production stalled.

This revolt did not occur in isolation or emerge out of nowhere, the Sixties were important for the ways in which politics became part of people’s everyday lives. Protests against the Vietnam War across the world, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the Cuban Missile Crisis and allure of Castro and Che Guevara had politicised student groups in France but also in the US, Europe and the UK. Moreover, the Sixties were a contradictory time in France. On the one hand, the decade is remembered as being the height of the ‘Trente glorieuses’ — the thirty glorious years or the economic boom following the end of WWII — the dawn of popular consumerism, the development of tertiary industries and a rise in spending power. But beneath the veneer, dangerous, monotonous working conditions and long hours persisted in factories, high unemployment remained, and workers wages had not risen along with the rest of the country. And while the markets were being liberalised, the authoritarian and nationalist, De Gaulle held the majority of mainstream media organs under his thumb.

Further, France’s empire was crumbling. Algeria had achieved independence, and the fallout from the bloody Algerian war saw the arrival on mainland France of over half a million North African men and women from the former colonies. Housing conditions in Paris made visible the gap between rich and poor. The growth of shanty slums around the outskirts of the city and at the university at Nanterre made palpable the divisions in society. Urbanisation resulted in the emergence of the new towns and high-rise blocks that were to become emblematic of the social fracture identified by Jacques Chirac in the 1990s. These questions and conditions were all factors in igniting the spontaneous popular uprising of May ’68. And their anti-capitalist, anti-repressive and anti-imperialist messages as articulated by the Atelier Populaire still resonate with issues in the contemporary West.

Signifying ’68

The Atelier Populaire emerged then out of a tense crucible of political turmoil and nationwide strikes happening in Paris in May 1968. On 13 May 1968, after days of street fighting, police brutality, and a march of over million people through Paris, art students at the illustrious Ecole des Beaux Arts in central Paris, occupied their school and set up poster printing presses on its second floor.

Philippe Vermès, a photographer and member of the Atelier Populaire, has described these posters as ‘weapons’ in the popular struggle against state authoritarianism and oppression, capitalism, imperialism, to be pasted on the walls in streets and factories all over Paris. Some of the key features of the Atelier Populaire was the anonymity of the posters produced, their methods of production—cheap silkscreen rather than more expensive and slower lithographic processes, and their consideration of function (as a communication tool) over form (although the form of these posters tells us much about their effectiveness and their relevance today).

Atelier Populaire rendered art as action. And this legacy has endured. Theirs remains a powerful aesthetic that crosses historical and geographical boundaries. In its contemporary evocation, the language of Atelier Populaire creates memory knots, linking popular uprising today with revolts of the past. In our increasingly privatised cities, these calls to think otherwise than the media would have us do, are reassuring signs that dissidence is still alive and possible.