17 March 2023

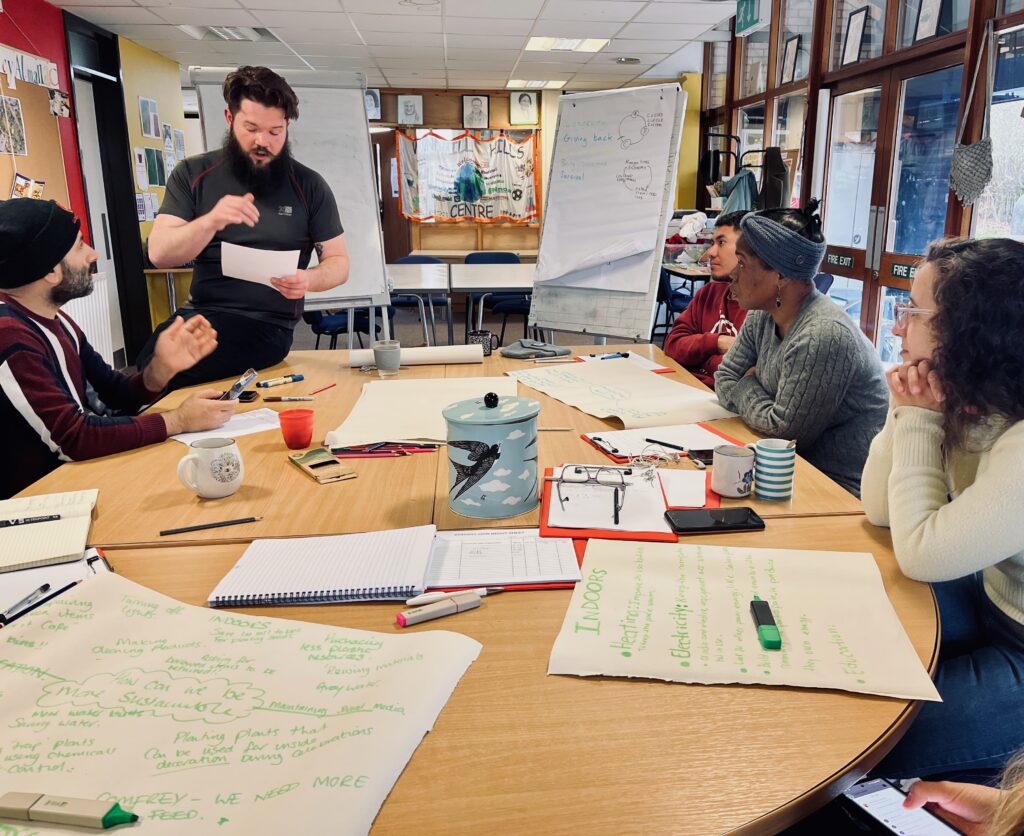

Today is the first day of a programme dedicated to fostering Sustainability Champions amongst the volunteers of The Comfrey Project. Cal, the lead horticulturalist, has set up the room so that it feels like an intimate classroom; the whiteboard ready with questions, and notepads and pencils for everyone around a single desk. There are six volunteers along with myself and Nicola (Session Coordinator at TCP). The knowledge being brought to this table comes from Chile, Syria, El Salvador, Congo, Argentina and Pakistan.

Our first task is to define ‘sustainability’. I find this activity useful in the way Cal approaches it. The insistence that there is no single definition opens the ground for discussion, inviting the volunteers to consider what it means for them today. Colette is unsure of the word in French. We translate it as ‘durabilité’, and already there is something interesting here. The word’s temporalities are more vitally tangible in French than in English. ‘Sustain’ seems to place emphasis on the notion of resistance and brings ideas of ‘effort’ and maintenance’ to the fore. I am reminded of Bergson’s distinction between ‘temps’ and ‘durée’. ‘Time’ made distinct from ‘duration’ by Bergson to refer to the mechanistic ticking of minutes on an objective device, the fiction of immobility contained in stations of the clock, the spatial line. Bergson’s distinction tried to account for the difference between this time, and the human being’s experience of temporality. ‘Duration’ refers to the subject’s experience of time’s progressive quality, its movement and incompletion. There is something to think with here as regards ‘sustainability’ and what we might emphasise when it comes to growing practices and attitudes to land. The temporalities of it, the mobilities and progressions that define life (from soil microbes to fungi, and magpies to humans) in the garden. The incompleteness of ‘death’ when considered ecologically, one thing becoming another thing and elements returning to life in loops. Entangled life spans and body masses moving and changing together. These kinds of conceptual trajectories are imminent but not openly teased out today though. For us, now, the question of practice and the sharing of practices is more pressing. There is a desire for applications, and to share stories from our respective countries of best and worst practices in terms of sustainable industry, farming, conservation and everyday attitudes to waste.

The various definitions of ‘sustainability’ that emerge from our brainstorming activities speak to values. For Priscilla, sustainability is ‘something that meets your need without compromising future capabilities’. Geovani emphasises conservation and the protection of the planet’s resources, using recycling as an example. Assadoula talks about not compromising future generations’ ability to meet their needs. Colette speaks of the time of things in the ground and how long it takes for waste like plastics to disintegrate. For Estefania the accent is on attitudes — a responsibility to think sustainably, to think about resources. And from this kind of awareness, towards acting ethically so that systems can work with as little human interference with nature’s thrifty loops as possible. The principles we share are teased out and these include: future thinking around resources, compromise and and understanding of limits. Cal translates this to the scientific language of the closed circle system, where things are created, used and returned to the earth, from the which the process of creation can begin again.

We think about these eternal returns, of nothing being wasted or lost. We think about the ways in which we break this loop over and over again. Nicola’s session on the time it takes for various items that proliferate in our shops and homes to break down is remembered. The endless search for new markets, inventions and customisable lifestyles lauded by the economies of the global north is recognised in its profound dissonance with the ecological rhythms necessary for healthy habitats and biodiversity.

So we ‘stay with the trouble’ (Haraway) and resist overwhelm and outrage to instead think about the question of what we can do to alleviate anxieties around all of the systems we cannot control, and how to take ownership of our everyday activities so that they correspond with these values. So that we don’t break the loop, or break them as little as we can. We think of all of the decisions we make everyday and this kind of thinking brings into our awareness the life of things beyond our immediate experience of them. Simple questions really:

- Where does the thing come from?

- How will I use the thing?

- Where will it go?

How can we prevent the loop from ending? The volunteers give examples from their countries of origin of ways that people have tried to balance need and preserve the circle. Clothes in Chile are recycled to make yarn. But, Estefanfia points out, this requires a lot of water. Bottle tops in Argentina are used to make toys. In El Salvador car tyres are converted into flower planters in gardens. We talk about the need for education, how in El Salvador water is sold in plastic pouches that are then thrown away. We talk of punitive justice — the need to tax people according to how much or little they recycle. And of the need to enforce these laws; regulation in Chile is inconsistent. We discuss the hierarchy of needs and this brings us to the ways in which social and environmental justice are entwined.

Assadoula tells us about Mirpur Khas. This place is known as the ‘City of Mangoes’. When I research the city, I find it has a population of about a quarter of a million people, and the city claims to have 252 varieties of mangoes, with the most famous variety being the Sindhri Amb, which means the mango from the Sindh. There is an annual harvest festival which showcases the renowned produce and which takes place in June. This is an industry which seems to work to sustainable principles. Farmers take the long stems of the mango plants and transport them to cattle farms to feed the cows, and the cow manure then feeds the soil. Nicola tells us of the brewing industry and how the grains from breweries were spread on farmers’ fields to feed the earth and the grass which grew there fed the sheep. Thus we identify the circle — the plant material is used to feed the dairy industry and the industries, to greater or lesser degrees are sustainable. But, we acknowledge that this circle is more like a web as there are so many off-shoots to these circles that they soon become entangled in ways that we at our small table are ill-equipped to trace.

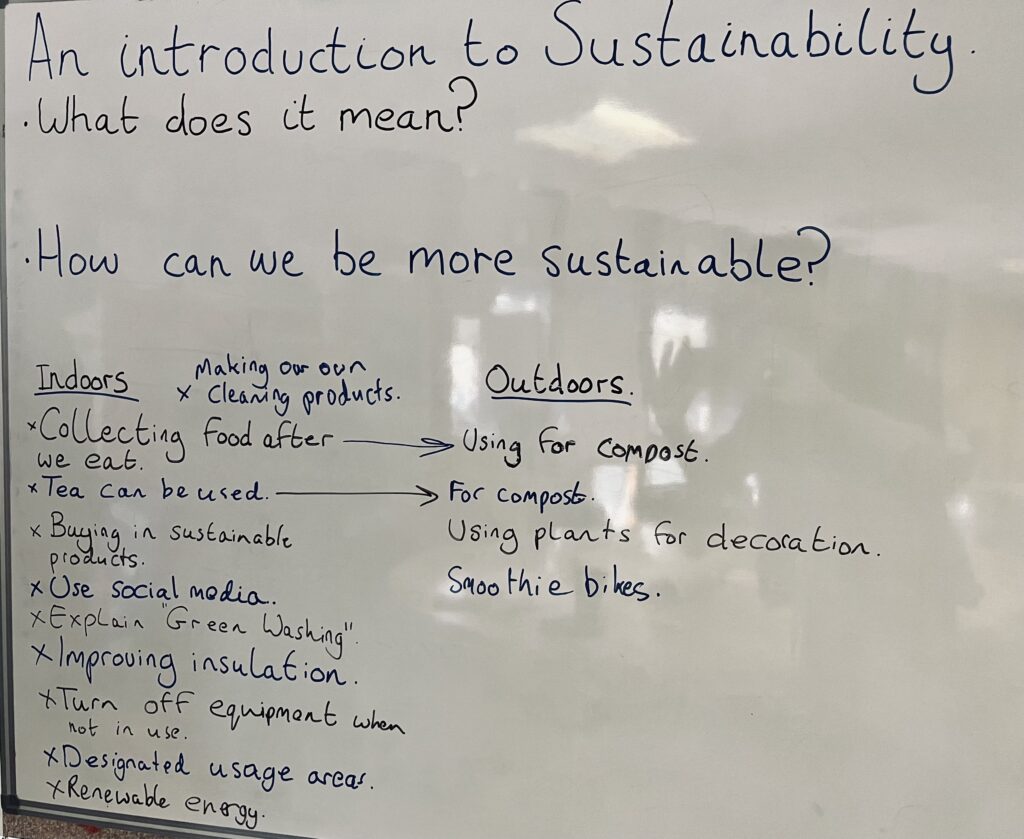

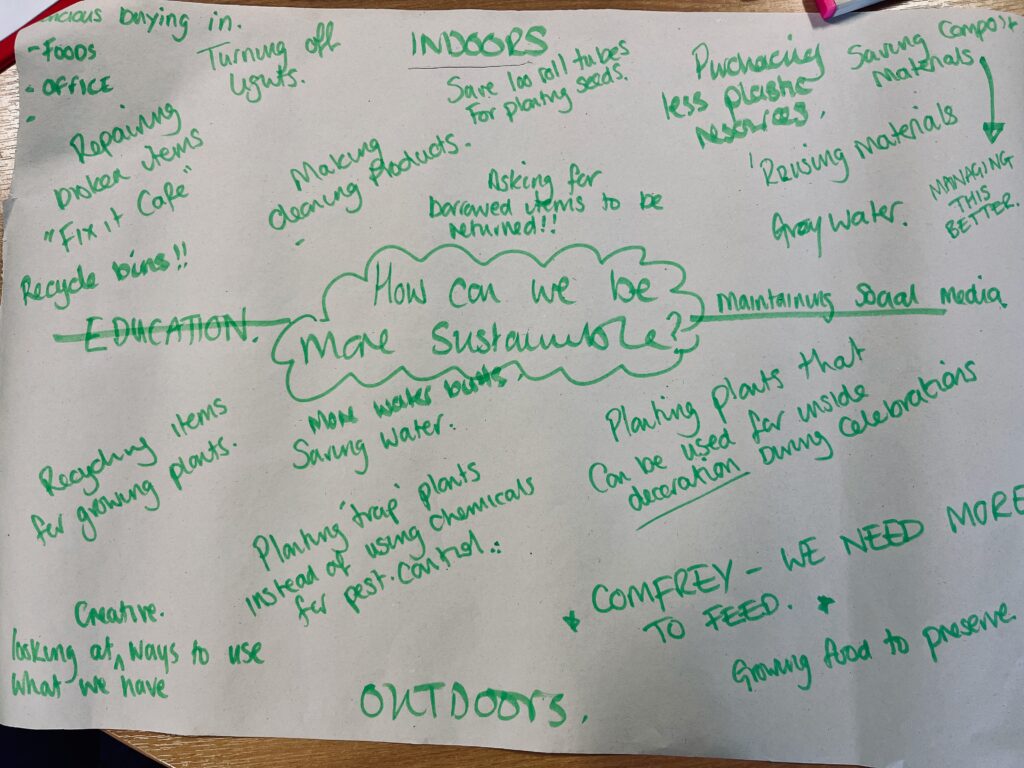

The remainder of the session is dedicated to thinking about sustainable actions that we can take around The Comfrey centre, both indoors and out. I will write more on each of these as they are practiced and in other blog posts.

At this point, while inspired to rethink some aspects of consumer choice, I am aware of the fact that I have a choice. There is a nagging anxiety and I am concerned about the structural differences in agency that are present as we undertake activities. Given the trauma that many of these volunteers have experienced, given the complexities of the situation they face here in relation to the the UK Home Office, how can we find ways to valorise the life experience, breadth of knowledge, expertise (ecological and otherwise) and creativity present in this room? I am writing late in the evening, and ineffectually, but it is important to be wary of the ‘academic voice’.

I am interested to see how The Comfrey Project creates room for the volunteers to contribute, to change minds, for voices to be heard and for knowledge to be shared. My project, the project I am searching for, is how to create platforms—political, cultural— where that knowledge can be heard and can matter. How to use conceptual and material tools to do this, and how to bring the knowledge and experience of community gardens to bear on planning processes. For now, I am simply gathering a trace of these myriad intersections that occur on this site in Gateshead. This place that brings into contact vast durations, diverse generational histories, wounds from complex neocolonial exploitations, children with three and four languages, people with professions, skills, knowledge and expertise waiting on a letter from a system that proliferates anxiety through delay; the suspension of a ground on which to settle. This place offers an interim ground perhaps. A fragile site for bridging cultures that works because we engage from our cultural positions with nature, such as it is moulded in this small plot of land in Bensham.