09 March 2023

Today, working with The Comfrey Project meant being able to take part in the Bees of Bensham ‘Go and See Visits’. This visit is to the Great North Museum, Hancock and an introduction to ERIC – the Environmental Records Information Centre of the North East. The session was hosted by Fiona Greenwold, engagement officer for ERIC, NE, aimed at residents of Bensham and Saltwell, and focussed on wildlife and biodiversity surveying: Why surveying wildlife is important and how anyone can survey.

This kind of grassroots education is exciting, fun, and empowering. It suggests a way of looking differently at patches of the city that legislation labels ‘brownfield’ and that we’re encouraged to think of as ‘wasteland’. Listening to Fiona opens these spaces out; they become whole vistas. Seemingly empty, we learn how to look, and discover they have been teeming with life all along. Not only that, this visit prioritises amateur, voluntary action—each person’s ability to respond to global biodiversity loss in meaningful, local ways by contributing to the project of wildlife and biodiversity surveying.

The March snow means I arrive a little late but still in time for introductions and chats over packed lunch. E’s friendly face from The Comfrey Project greets me first, and there are some familiar faces from Dingy Butterflies whom we met at the ‘Best of Bensham’ event at the Windmill Hills garden last summer. We introduce ourselves, coffee is proffered, apples unwanted by some are shared with those who want them. The informality means the atmosphere is welcoming. Nowhere a sense of one person having more reason to be there than another. No intellectual strutting. No nonsense. What is palpable is a concern to share stories, experiences, and opinions in a room where values and concerns intersect. It feels enlivening to realise that this is not the end of it either—beyond cups of tea and cosy chats, we are going to learn how to take action and get involved easily in connecting our observations of local places to wider national data networks and political apparatus. We learn that individuals—amateur, professional, everyone from my granny to your 5-year old—are vital to tracking wild things and enriching awareness around biodiversity.

The first part of the visit is to the library and archives of the museum. It’s like being let into a secret to gain access to the more tucked away parts of a museum space. Even better to know that that secret is not jealousy protected by any kind of paywall: the library and archives of the Great North Museum: Hancock are fully open to the public. The reading room is a revelation. Bright with natural light, the room is compact but spacious enough to house hundreds of books. Titles on butterflies, The Natural History of Flies, and some volume called A Dipterist’s Handbook — I have no idea what a ‘dipterist‘ might be! This is a space for curiosity and the sense of expansion that comes from looking at a bookshelf: the feeling we get knowing each volume sitting there quietly holds an entire world and all it takes is for the reader to unleash it. We’re introduced to L, the newly appointed librarian, who has kindly taken out from the archive some botanical drawings by Margaret Dickenson for us to look at. Given it was women’s day yesterday, there are books on display about female naturalists and women writing on nature.

I spend most of the visit talking with the brilliant artist and beekeeper Barbara Keating. She explores aloud her concept of ‘bee washing’ in different contexts, from Paris to the North East, and shares her thoughts about colony collapse, and why she refused to bring hives into Newcastle city centre until they were needed in the pollen studies being undertaken by Northumbria University researchers. She tells me about her fascinating artistic project, ‘Bee Banquet‘, where she feeds guests on foods that form the diet of bees while footage of bees in the hive is projected over the human diners. Barbara is a passionate advocate for community action and education around biodiversity and pollinators. From our brief conversation, I come away with a richer understanding of the various species of bees, the dangers of species dominance if we flood certain areas with only honeybees and the needs of pollinators. What will urban bees eat? How many other honeybee hives are in the surrounding areas? Thinking with bees… She has given me a framework for thinking through a piece I’m writing on the political ecologies of community gardens in Grand Paris, and I am now looking forward to citing her work in article.

We return to the common room, where Fiona presents ERIC, their work, and how we can and why we should get involved with wildlife surveying. ERIC works with professional wildlife recording groups, but also with individuals and amateur community groups. She explains to us how we can all be involved in collating environmental data which is then used to help inform policy and actions taken around nature conservation. ERIC is based in the Great North Museum: Hancock and operated by the Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums.

Fiona’s presentation is informal, accessible, and enabling. She tells us that the free app., iNaturalist, is the best way for amateurs to get involved in mapping biodiversity and wildlife in their local area. It works like this—see something wild (let’s say some kind of flower, bird, beetle, a hedgehog, frog, rabbit etc.), photograph it, upload the photo to the app which scans it and tells you the name, location (if you grant permissions) and time of sighting. The iNaturalist data is fed into ERIC’s databases and others. The data is used in various ways, and is significant in making planning decisions for example. Over time, it also allows us to understand the impact of habitat loss and climate change on specific populations in specific ways.

Beyond this, this app might be one positive tool for fostering a sense of belonging with, and connections to our local landscapes. Important in urban communities that still live the traumas of deindustrialisation, where being ‘left behind’ often leaves people feeling powerless and, later, disconnected from their local places. Might simple networks that enable us to take some kind of action constitute a small tool (in what needs to be a much bigger arsenal) for restoring people’s sense of agency and worth? Can the ability to respond in modest ways like these help reduce the sense of overwhelm that media assaults tend to produce? An overwhelm that leads to disengagement—that knee-jerk urge to curl up in the foetal position and leave it all to someone else. Does media saturation create the sense that it’s all beyond our power, and can small actions help us up off the floor to push back against that kind of mass media inoculation? Beyond the political (is there such a thing as ‘beyond the political’?) what I know is that when I open the app and start photographing my street, I hear the thought, ‘Fuck whatever government plan is cutting up neighbourhoods and ecosystems today, I belong to this world too and I can act for it’. It’s a relief to know that I’m not at all original with that thought.

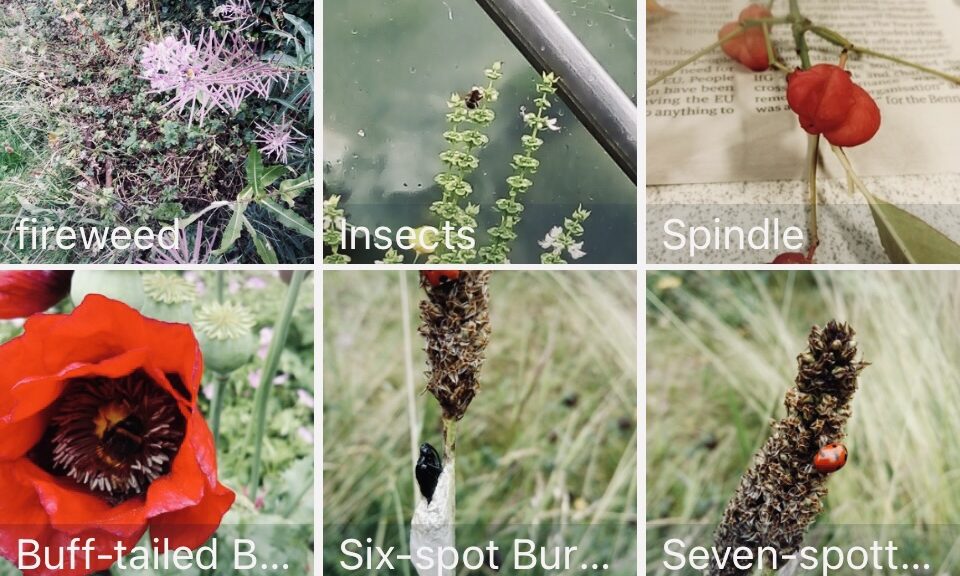

Doing a wildlife survey of The Comfrey Project garden at Windmill Hills is something Cal and I talked about. After today’s talk, I feel less dependent on expert advice before doing something. I turn on iNaturalist’s easy geolocation map and find the Windmill Hills site and am delighted to be able to see what kinds photos have already been uploaded and registered. They form the image at the top of this post. I’m hopeful that Fiona’s visit to The Comfrey Project in the coming weeks will be fun, that people will be as enthused about ERIC-NE’s work as me, and get us out looking closely at the ground—down with interest, curiosity and wonder—identifying plants, insects, and reframing old wives tales about ‘weeds’. We’re talking about when to schedule her visit.

The past few weeks have give me some insight into how interconnected a lot of non-profit and values-driven community organisations are in the North East. There is a sense of solidarity and shared purpose. It makes the overwhelm easier to confront and put in its place. The people come to the work from all different kinds of backgrounds, different experiences, but there is a shared energy that looks outwards, knots of understanding and values that chime. There’s a comfort in this that is invigorating, inspiring and makes you stand straighter.