Tag Archives: Design

OHD_PRS_0301 Swimming through Treacle

So today im going to talk about designing in GLAM, by telling you about my experience designing in the national trust. Which I have illustrated with this can of treacle. And this is because one of my national trust supervisors described trying to basically get anything done in the trust as swimming through treacle. And it feels like it encapsulates my experience of designing in the trust.

//

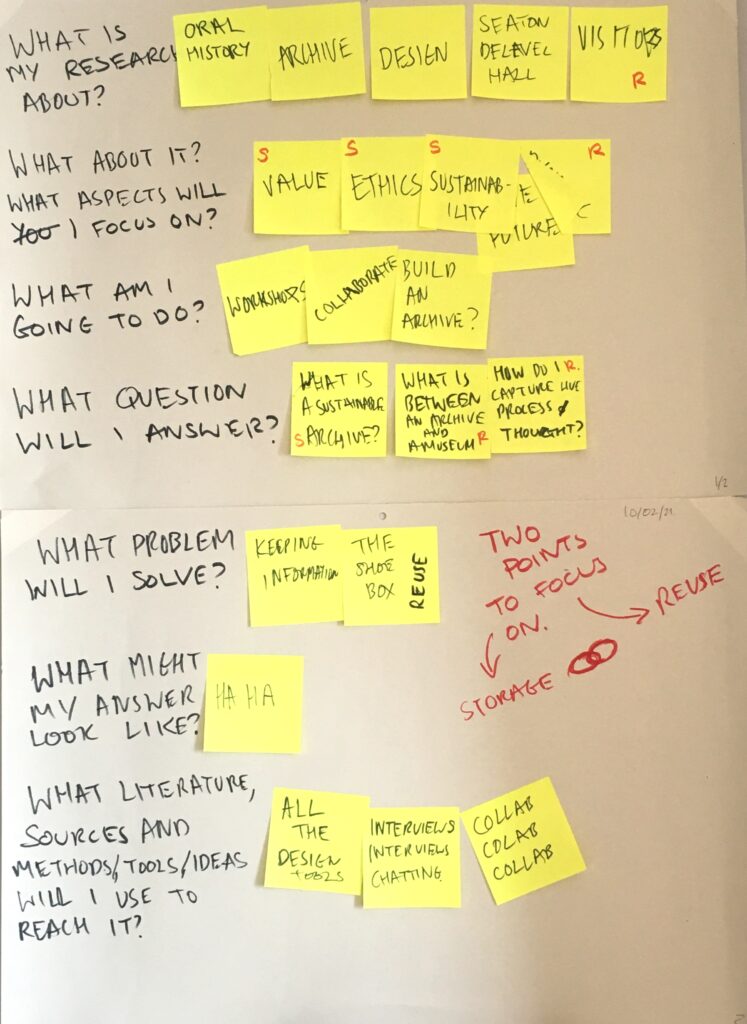

To give you an idea of what I mean. I’ll show you my initial project plan I made right at the beginning of my phd.

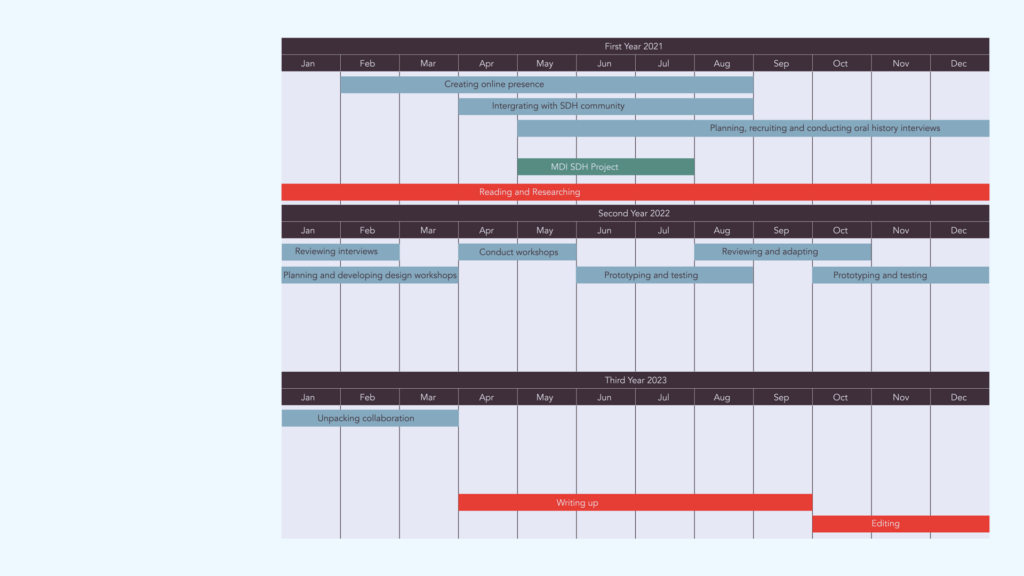

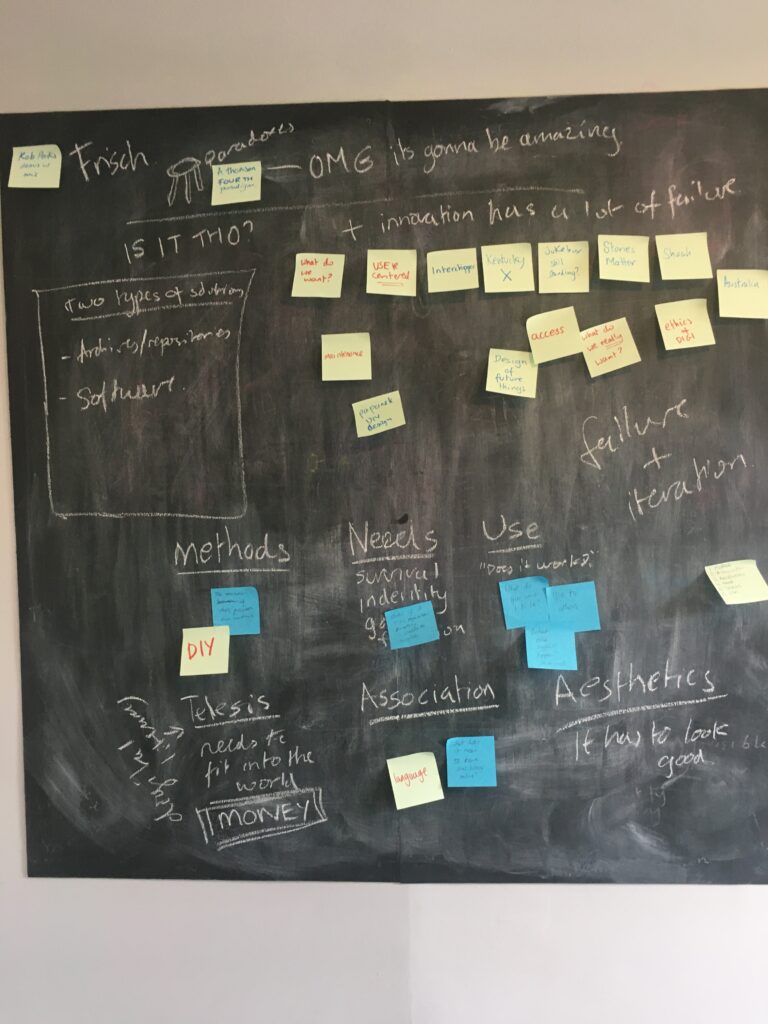

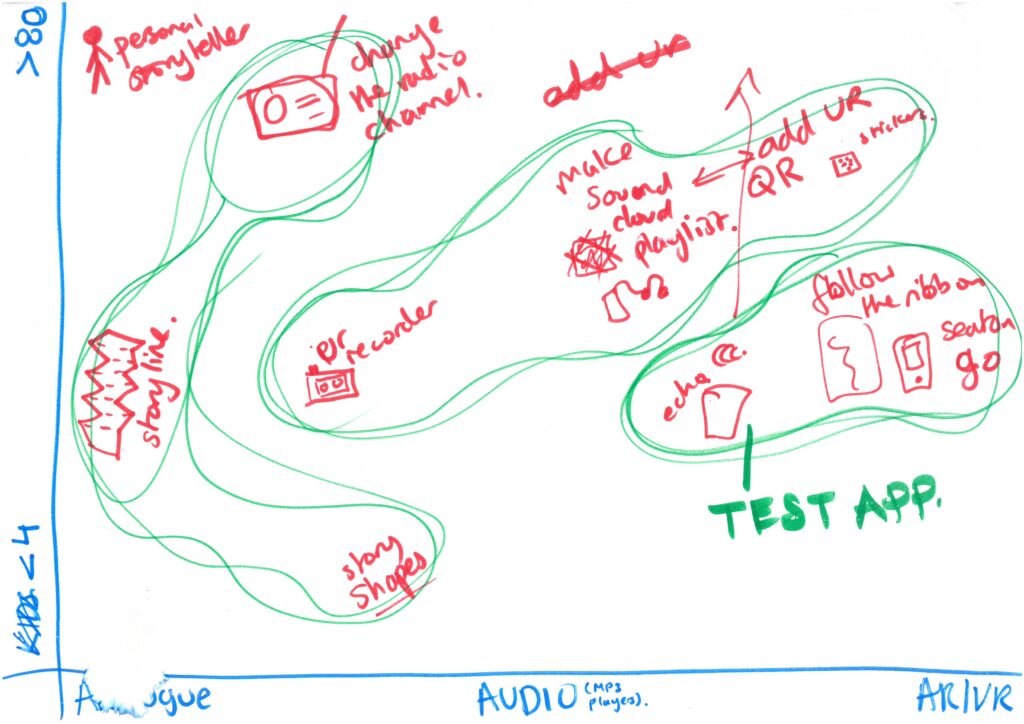

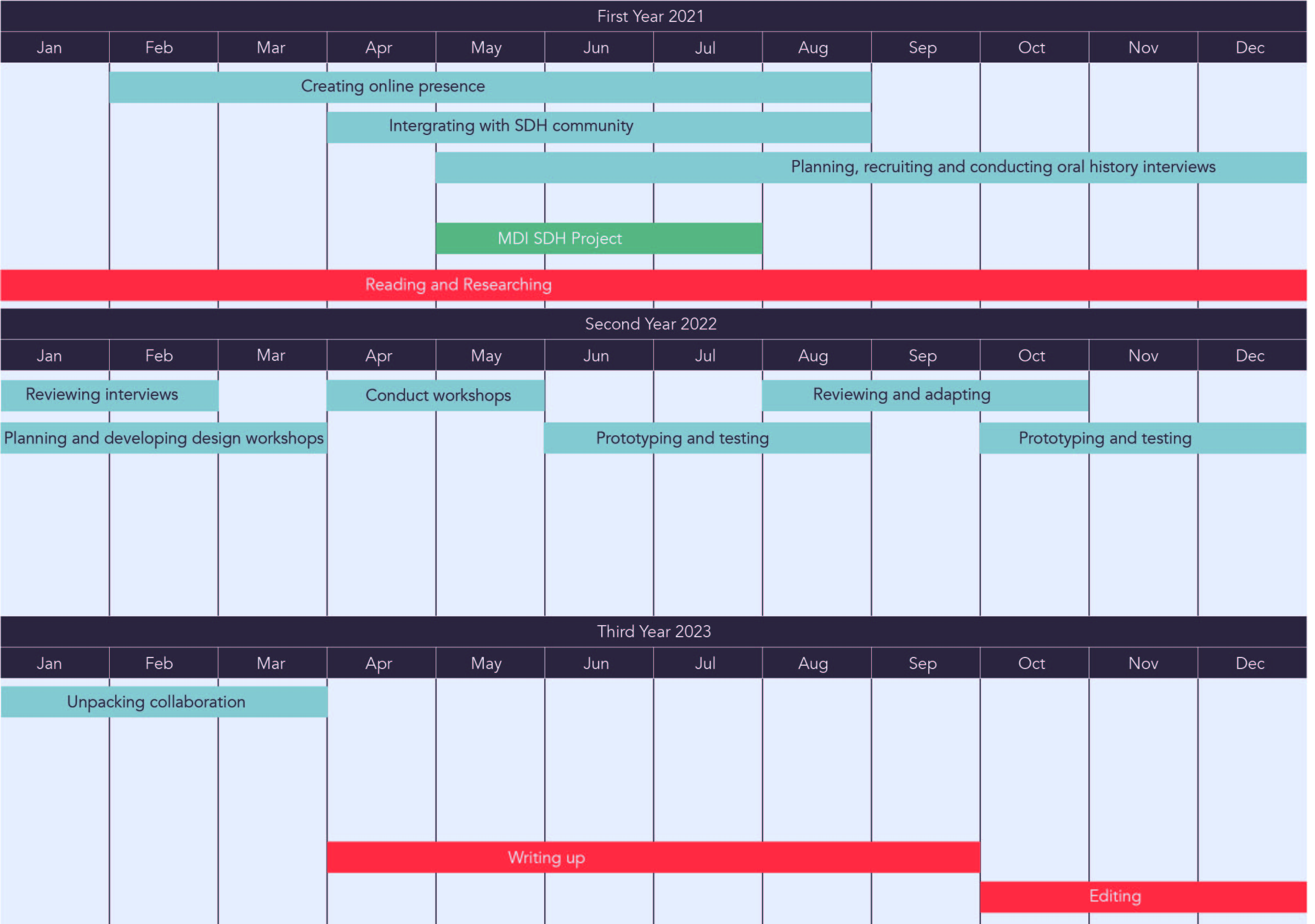

So quick bit of CONTEXT my phd was developed off the back of the final project I did for my masters in multidisciplinary innovation. The task for the project was create an oral history project at Seaton Delaval hall and one of our conclusions was this archiving of oral history thing, you could make a phd out of it. And so we did. And I was going to look at creating something that specifically allow visitors to reuse oral histories on heritage sites. So in my mind this was likely to be some kind of sexy software that would just be so sleek and amazing that all oral histories problems would be solved. And this was my original plan on how I was going to do this is this. Now pretty much everything about this is wrong. Firstly because it is three years instead of four years, it does not include any of the placements I did. But also the entire process just did not or could not happen.

[UNPACK PROJECT PLAN]

I did realise that the usual iterative testing process is just not really possible because but I could never properly test them.

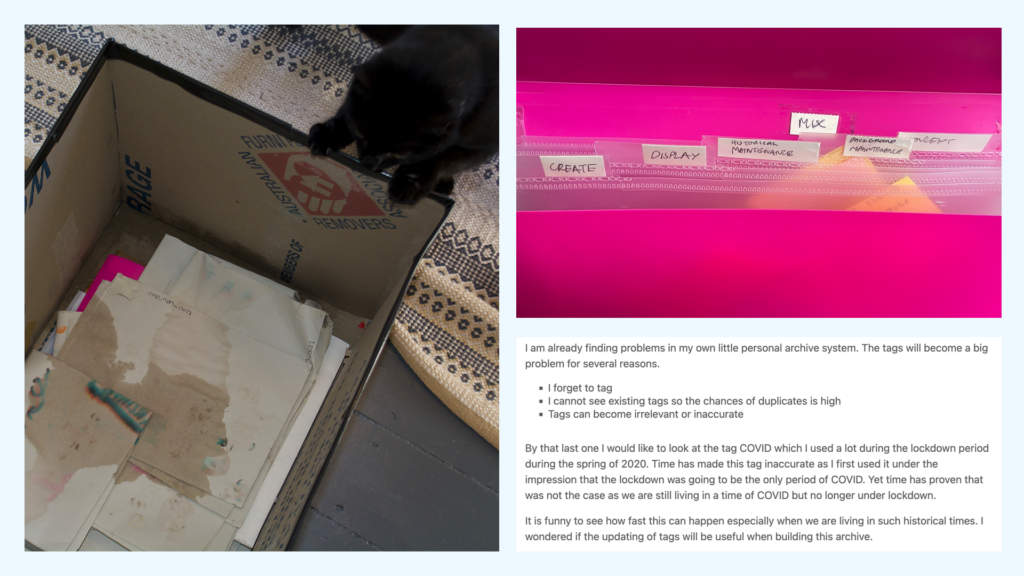

The only example I can give of iterative testing is with my own archive. But this has nothing to do with the working with GLAM bit.

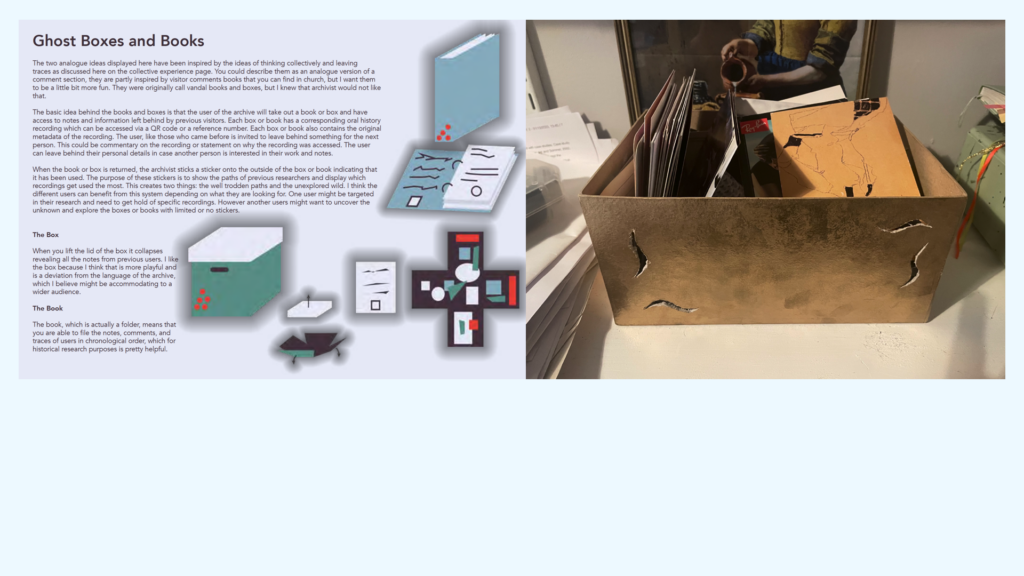

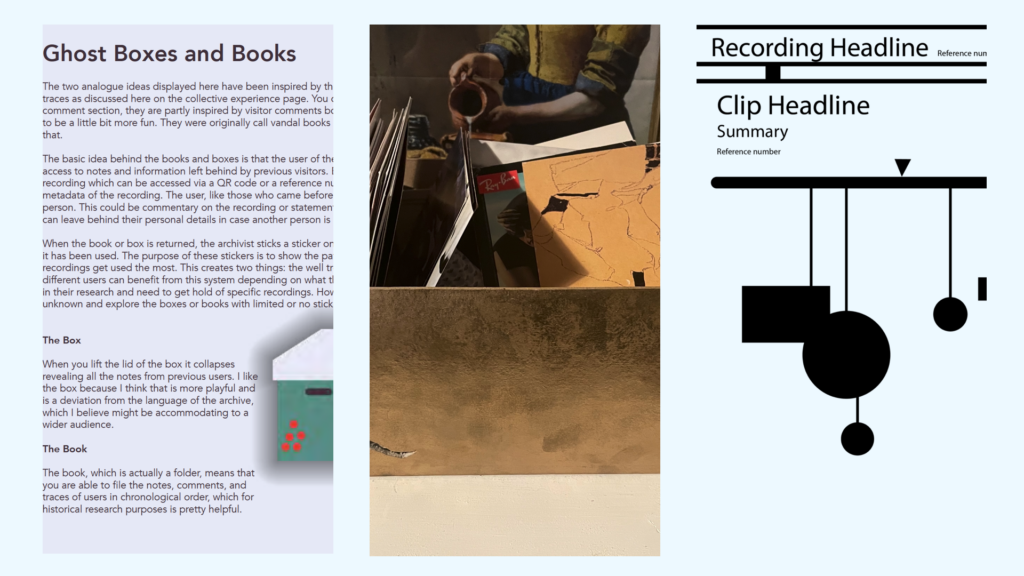

I did give prototyping a try and although I did not test them.

However I thought the lack of testing told me a lot about the design environment.

I could not test the ghost boxes because they did not know what material to give me to test this with nor did they have the space for it, and most importantly they did not want to make any promises. The sound box could not be tested bc you are not allowed to have external tech in Nt and what oral history was I going to possibly use. The transcription ribbon was also one that could not tested because what laptop would that work on. So the lack of testing was not a complete failure in the end.

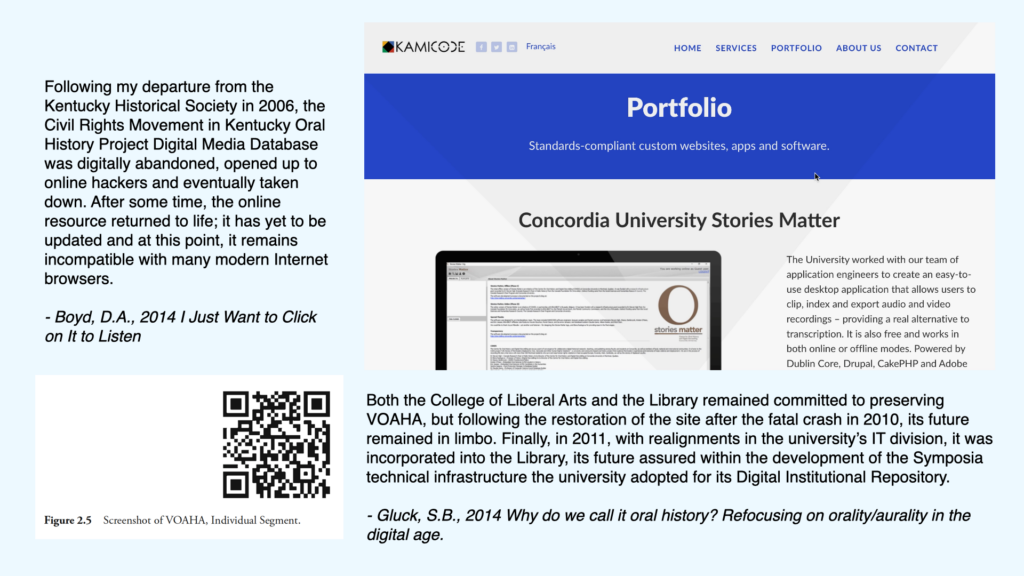

But I still need a new approach which I found after I looked at previous attempts at making oral histories more reusable. There have been a collection of attempts to make oral history more reusable. And most of them have failed ish. It is weirdly hard to do research into this because people did not really write a lot about when things failed. They publish papers on the super new tech and then they just disappear. Luckily there is one book that does talk about some failures. Boyd quote, VOAHA and stories matter

These all failed because people did not think about the maintenance of the work. And if we look at my prototypes you see the same issue. What these prototypes told me and the various attempts at making oral history more reusable. Was that it is not about what you make but about how you maintain it.

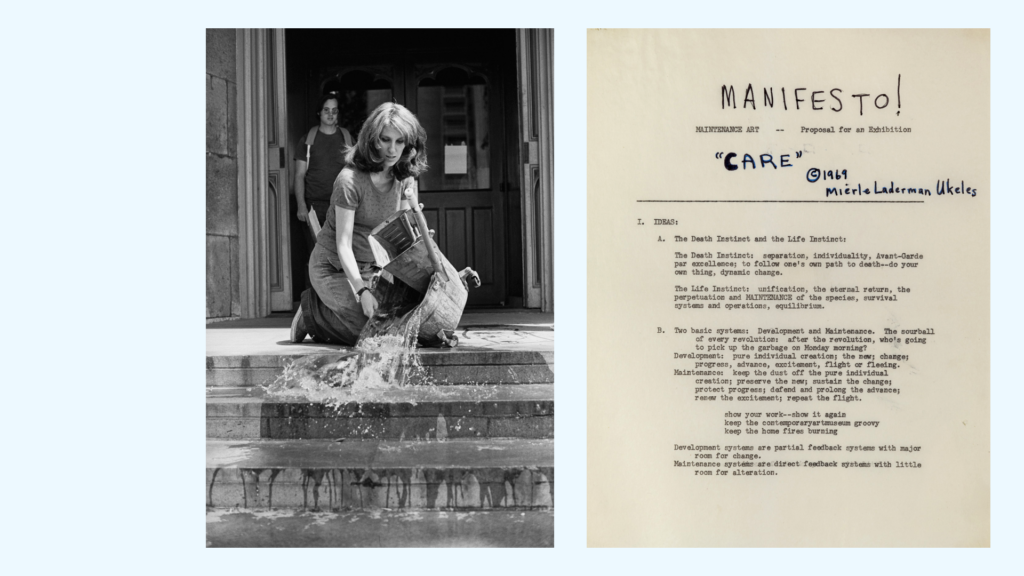

Which is how I get to Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Is a maintenance artist. She wrote a manifesto for maintenance art. Where she wrote the line “after the revolution who’s going to pick up the garbage Monday morning? I remember seeing her work during my time in art school and absolutely loving at the time but I had forgotten about it until it was mentioned by The British Library oral history archivist Charlie Morgan, who used this quote in a blog post about all the recordings that were made during the pandemic and how someone is going to have to archive these someone is going to have the clean up after the revolution.

So from this I wrote a manifesto for maintenance design, which I had totally forgotten I had written. So ukeles spilts the world into two systems in her manifesto the development system and the maintenance system, which she labels the death instinct and the life instinct. In terms of maintenance design I have put under the death instinct is that this is about drive by collaboration and the life instinct is simply life goes on. The designer is only a visitor to this space.

– labour

– limited resources (which also basically include labour. And I. Think that is also why I connected it to earth maintenance and looking after the planet)

So I decided to work through the lens of maintenance. but maintenance as a thing is really annoying because it is really hard to see if you are not part of it. IF you look t people who write about maintenance or infrastructure like Susan Leigh star a recurring theme is that you cannot see the value of maintenance until it breaks down. So my idea was that I would probably have to get very close to the situation in order to try and understand and map out the maintenance in these heritage sites, archives and look at how oral history needs to be maintained.

And this is how we get to Action research as a design strategy but while action research is normally the researcher going in and working with the stakeholders, but really what I did was work for the stakeholders. I literally went in and was like what do you want me to do. I have these skills how would like to use them. And so they would give me a task to do and then I would bring it back to them for feedback and they would yes no no no no yes maybe, not yet. In the reflective practitioner Schon compares being a reflective practitioner to what jazz musicians do, as they make it up and go with the flow. And that is very much what I had to do because no one tells what you need to know, either because they do not know or more often they simply do not have the time. I could have rocked up with my cute little sound box, they could not care less. They are thinking about the car park and whether the cafe has enough stock. You know how I found out the issues of IT at the national trust, my lovely supervisor was like you are tech could you sort this out and it was a nightmare. I then told the IT guy and he was like I’m gong to pretend I did not here you say that. You have to think on your feet the entire time and by working with or for them you can start building a better idea of the space you are designing in.

So action research was my strategy and under that came all these different case studies I was able bc my funding body is like go do placements. So what did I actually learn on these placements, well firstly my phd was going to be super unsexy.

– Seaton Delaval Hall:

research room design:

leaving room for change:

working with maintenance, leaving room for the stakeholders to make their own changes. It is about setting up a framework.

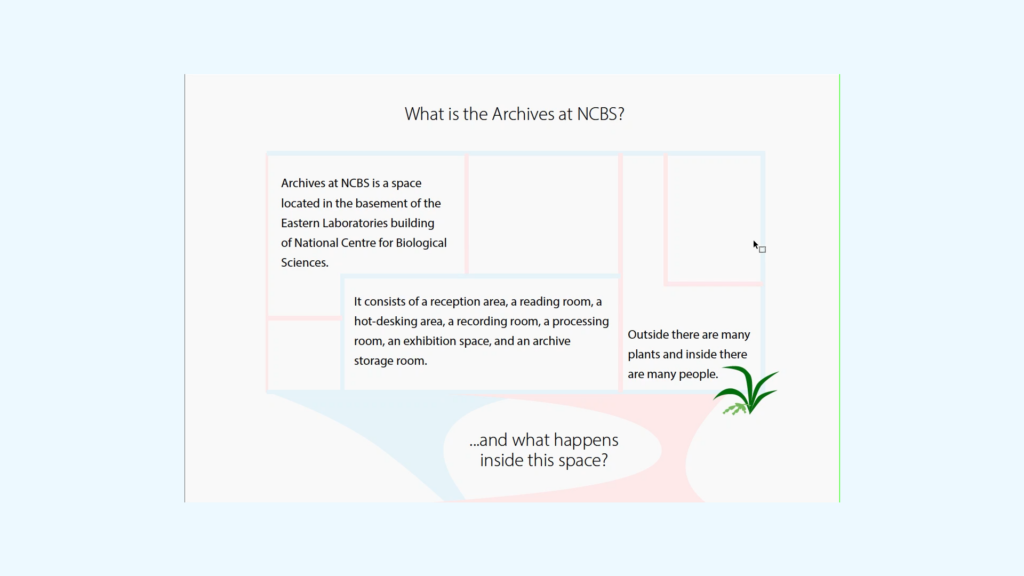

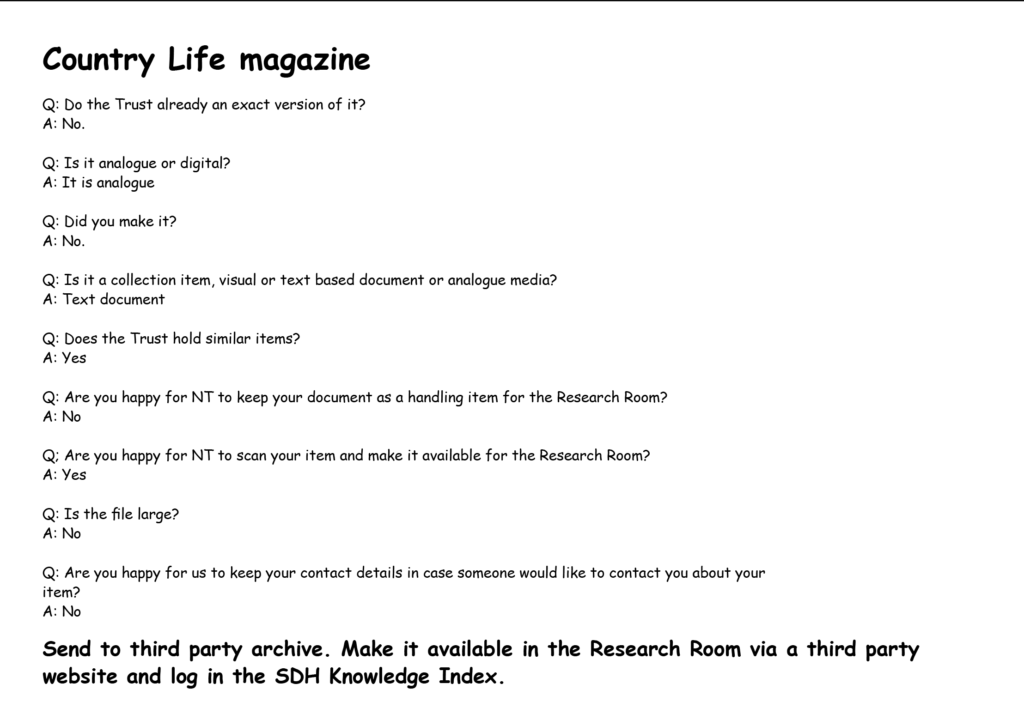

– NCBS: policy development: takedown policy and sensitivity check doc: have to really thorough think about what we mean by archiving: understand what GLAM does

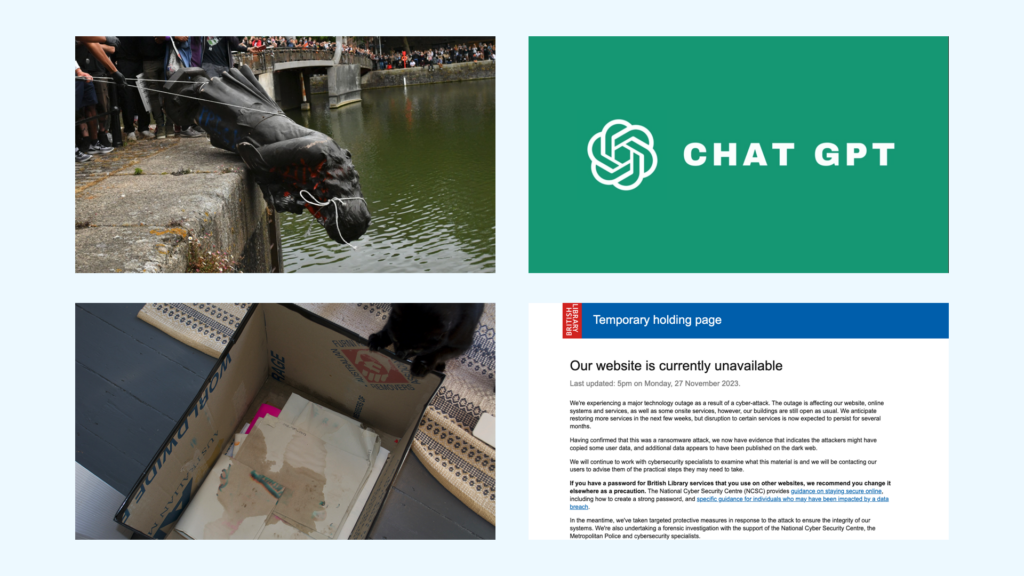

– bl: audits: what can history tell us: working with change

So I learnt some good things while on these placements

– working with maintenance is allowing room for the existing structure to absorb your work by offering a framework not dictating a single solution.

– what GLAM does. It collects people’s property and thats complicated

– things changes and this effects how we maintain. So although I am focused on maintenance I also recognise that maintenance has to move with the times otherwise it breakdowns down and we working to restore not maintain.

But what do I say if someone comes up to me and is like “how do I design in GLAM?” How do I swim through the treacle?

Well I can tell you what GLAM does.

1. It collects peoples stuff. It collects people’s property. It might be something they own or something they made. and there are laws, ethics, and cultural customs that are around this you cannot forget. Also they might change and vary between countries.

It does two things with this stuff. It keep it and it curates it. how long something is kept can vary from whenever an exhibition is finished to forever either way however long it is kept it must be maintain and safe. How it curates it is also deeply political and never truly objective.

So if this is the why and what. The how is creating the balance between creation/collection/development and maintenance. Or more simply said Change and stability.

First It is about spreading the resources you have other these two spaces. NCBS

And the second is to one big ol’ theory of change or risk assessment.

OHD_DSN_0283 Version One of the Methodology chapter

The Methodology Bit – Version One (very bad draft)

The above graphic was my initial project timeline. To say this is not how the project eventually played out would be an understatement. Both the initial chosen design methods and what I was intending on designing turned out to be highly inappropriate for the situation I was designing for. The central aim of my project was to develop a solution to encourage the reuse of oral history recordings, a problem infamously dubbed “the deep dark secret” of oral history (Frisch, 2008, p. 00). I was specifically looking at how to solve this deep dark secret with public history institutions, museums, heritage sites etc. My case study was the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall just north of Newcastle. I assumed I would make some kind of software or product to help ‘solve’ this issue, which would involve creating a prototype and then testing it out. However, within the first year it became apparent my plan was not going to work for two reasons. Firstly, my testing ground, Seaton Delaval Hall and National Trust were very risk adverse. The structure of the property and the National Trust in general is not a space where radical change or experimentation can happen easily, stability is key. Secondly, after researching the previous attempts of trying to solve the problem of oral history reuse, I realised me creating a new product was not going to work. There was something more fundamental that was being overlooked – maintenance.

Although there is little written on how certain attempts failed, what was written nearly always referenced how after the project money ran out the software or website fell apart (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014, p. 9). This issue of oral history reuse is not about snazzy interfaces but about maintenance, politics, and wider complexities of institutions. Therefore, maintenance became the lens through which I did my project, specifically the way the performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles describes maintenance in her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!. For Ukeles maintenance is: deeply undervalued in society; consist of many interconnecting boring tasks; and cannot afford to radically change (Ukeles, 1969). All three of these properties, but especially the latter two, led me to seek a methodology which could handle complex issues and be sensitive to the environment it is designing in, as I mentioned before the National Trust and the hall were risk adverse. I landed on Research through Design, a relativity young design methodology where the focus is not the creation of a product but creating new knowledge by using design methods (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). In my particular case this new knowledge would create a better understanding of how oral history recordings are/can/should be maintained. This in turn might lead to the development of more appropriate solutions to the deep dark secret of oral history.

I will unpack the concept of Research through Design or RtD and how it functions within the context of my project. Since the field of design is broad and there are the various interpretations of RtD, I will focus on the use and understanding of RtD within the field of Human Computer Interaction or HCI and Interaction design or IxD. HCI and IxD handle information technology and my work addresses the management of archive material, which is a form of information. Therefore, borrowing from HCI and IxD feels appropriate because their main purpose is to understand and design for the relationship between humans and their technology, which within my project can vary from analogue archive index cards to online catalogues systems. I will explain how RtD is explicitly suitable for researching and understanding maintenance systems, through its use of simultaneous problem and solution development, which originates from Rittel and Webber’s concept of ‘the wicked problem’. Following this I will focus in on what design methods I used as part of my research to generate knowledge. I will also explain how this knowledge and research is then presented in a way to demonstrate rigour.

Understanding RtD

RtD is a relatively young concept and it currently does not have a fixed methodology, which seen by some as a positive and some as a negative (Gaver, 2012). Although there is no strict definition of RtD there is consensus that, firstly, RtD as a method is excellent at handling complex problems, and secondly, the goal of RtD is to produce knowledge (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). The former is helpful to me because I am looking at the maintenance of oral history recordings in public history institutions. The latter is helpful because I was unable to do any thorough testing of prototypes as was originally planned, instead I will create knowledge which can help individual public history institutions understand and handle their own versions of the oral history reuse issue. To start with let us investigate the how RtD helps us understand maintenance infrastructures, and then move to looking at how creating knowledge is more appropriate for tackling this issue.

Wicked problems

RtD, like many other methodologies in design is focused around solving complex or ‘wicked’ problems. The term ‘wicked problem’ comes from the paper, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber. The origins of the wicked problem come from the 1960s where designer shifted from exclusively thinking about the product they were designing to thinking about the systems around the products and the wider systems of our society. These systems of our society were becoming increasingly complicated due to the rise of more complex technologies, and increased awareness of societal inequalities and the emergence of Post-structuralism, which challenged the idea problems could be defined in an objective manner (Bayazit, 2004, p. 17; Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156). What became apparent was how the Newtonian and more scientific problem-solving methods and theories used in the early half of the Twentieth Century could no longer handle the complexity of the post World War Two problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973). The types of problem which could be solved using this method, where a problem is easily defined, and solutions either fail or succeed, Rittel and Webber refer to as “tame” or “benign” problems. And the complex problems appearing in the latter half of the Twentieth century are referred to as “wicked problems”. Wicked Problems are societal problems involving multiple stakeholders and are of a complete opposite nature to benign problem. They are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to define and there is no correct solution, only ‘better’ or ‘not bad’ solutions (Rittel and Webber, 1973).

Through their explanation of the properties of wicked problems Rittel and Webber do give a simple structure to the ‘solving’ of wicked problems – simultaneous problem and solution(s) development. This has become the basis of much of design research in the last fifty years including RtD. The idea of passing between the editing of the problem definition and creating solutions is a way to continually challenge the underlying assumptions made during the initial formulation of the problem (Zimmerman, et al. 2007, p. 495). In order to understand why the wicked problem, simultaneous problem and solution development, and the continuous challenging of assumptions is helpful in the context of reusing oral history recordings within public history institutions, you need to understand the nature of maintenance.

The invisible web

In Ukeles’ manifesto there is the line: “Maintenance is a drag: it takes all the fucking time (lit.) The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom” (Ukeles, 1969). Maintenance and how it works is boring. The sociologist Susan Leigh Star makes a call for the study of boring things in her paper the Ethnography of Infrastructure, and although Star does not directly use the word ‘maintenance’ in her work, her idea of infrastructures has been used to better understand and unpack maintenance (Graham and Thrift, 2007). There are several of Star’s infrastructure properties which can help to understand maintenance infrastructures, such as:

- “Embeddedness” – Small maintenance infrastructures live within larger maintenance infrastructures (Star, 1999, p. 381). For examples, cleaners, janitors, and IT support are all part of a wider maintenance infrastructure of a building.

- “Reach or scope” – As is written in Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! “It takes all the fucking time.” Maintenance is not a one-off event, it goes on forever (Star, 1999, p. 381).

- “Links with conventions of practice” – Those who work within an infrastructure will develop habits which are heavily influence by the technology they use. (Star, 1999, p. 381).

- “Built on an installed base” and “Is fixed in modular increments, not all at once or globally”- The maintenance infrastructure did not appear overnight it was built bit by bit in reaction to changes in the community it is meant to support or the technology it uses (Star, 1999, p. 382). And as Ukeles says there is little room for change once it exists (Ukeles, 1969).

However, it is specifically the “invisible quality” of an infrastructure, where the idea of wicked problems and simultaneous problem and solution development come in.

A maintenance infrastructure is a wicked problem. It is a complicated web of interconnected elements which is slowly, yet consistently, evolving in order to hold off any collapse. It is made up of technology, people, and their actions or labour which stops breakdowns from happening (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 3). These three aspects can be invisible in one way or another. Technology becomes invisible because it is buried underground like pipes or is suspended high above our heads like telephone poles. People can be invisible because maintenance workers are made invisible by either the location or the time the work takes place. For example, domestic workers stay in private homes and commercial cleaners work outside opening hours (Star and Strauss, 1999, p. 16). Within the context of my project the technology and the people are both invisible because the majority of work happens inside the closed doors of a storage space or office. The work associated with the maintenance and keeping of historical items, like oral history recordings, has always been invisible, however, like everything else, it has only gotten more complicated with the rise of technology. Technology has, in a way, opened up the storage space through the creation of digital archives, but this has also buried all those who maintain historical material deeper behind screens and servers. Actions or work can also be invisible. This is often emotional labour or other forms of care. A nurse is a great example of such a worker, because their work with patients is often “taken-for-granted” due to its completely intangible nature (Star and Strauss, 1999, p. 15). Oral history also has elements of invisible emotional labour because it relies on living humans to tell their stories. In order to ‘extract’ these stories the oral historians have to make the interviewee feel comfortable, which often involves many cups of tea.

In addition to the three main elements of a maintenance infrastructure being invisible in one way or another the outcome and function of a maintenance infrastructure also somewhat invisible. The main aim of a maintenance infrastructure is to keep things from decaying (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 1). However, because the product of the labour is a lack of decay it is difficult to quantify since there is no measurable outcome, only the absence of something, making it invisible. Everything about a maintenance infrastructure, the technology, the people, the work, the outcome, can or is invisible. These various elements are invisible in different ways making it additionally complicated. To solve the issue of oral history reuse in public history institutions we need to understand and map its maintenance infrastructure. This maintenance infrastructure and how it comes together is a wicked problem and the mapping of this maintenance infrastructure is equivalent to defining the problem in simultaneous problem and solution development. But in order to map the maintenance infrastructure we need to make it visible. Luckily how one makes an invisible infrastructure visible is relatively simple — you break it.

“The normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks: the server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout.” (Star, 1999, p. 382).

You can see this with the previous attempts of solving the oral history reuse issue. Those who have written about it state how the eventual collapse of the website or software revealed how much the systems relied on the maintenance of digital systems (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014, p. 9). The breakdown of the solution developed by these projects revealed part of the maintenance infrastructure for their particular situations. However, the information was only discovered after the project was finished, therefore the information could not be fed back into problem development.

Breaking the maintenance infrastructure to gain information for simultaneous problem and solution development is not an option; the system must keep maintaining. This is one of the reasons why the National Trust and Seaton Delaval Hall were worried about me widely testing prototypes, they were apprehensive to anyone who might disturb the delicate equilibrium they have in place. As I mentioned in the introduction the National Trust’s aversion to risk and testing, and the history of attempts to solve the oral history reuse issue led me to move away from designing a product. This is where RtD becomes different to other forms of design methodologies which also used simultaneous problem and solution development, because instead of creating a product or some other form of full realise system, it creates knowledge.

Knowledge, not a product

To understand why RtD focuses on creating knowledge rather than a product and why this is helpful within the context of mapping maintenance infrastructures through simultaneous problem and solution development, we need to look at how knowledge is defined within the terms, ‘research’ and ‘design’. Generally, research and design have often been pitted against each other, as Stappers and Giaccardi show in this table in their chapter Research through Design.

| Research | Design | |

| Purpose | General Knowledge | Specific Knowledge |

| Result | Abstracted | Situated |

| Orientation | Long-term | Short-term |

| Outcome | Theory | Realization |

Table 2.1 – In general, the terms ‘research’ and ‘design’ carry different connotations (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017)

The definitions in the table above originate from the different types of ‘knowledge’ produced by academic and vocational forms of design education. Within the former, the ‘knowledge’ produced is in the form of research such as theories, frameworks, and matrixes, which can be used by others. The latter’s ‘knowledge’ comes in the shape of more tangible products for very specific situations (Glanville, 2018, p. 14; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). RtD sits somewhere in the middle where it produces knowledge which can be used by others but this is still grounded in the specifics of real-world application (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). According to Zimmerman et al. the outcomes of RtD can vary from new design theories, frameworks or philosophies to artefacts offering a possible new future, to tools to encourage wider discussion in the field (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311). However, the goal overarching of RtD is to produce knowledge used to simulate conversations with interested parties about possible futures (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017).

The knowledge created is purposefully ambiguous to make it more transferable to other situations and to allow it to be flexible when change does come. People are able to take the knowledge and interpret it for their own specific situation (Gaver et al., 2003). This recognises Rittel and Webber’s idea that a wicked problem is never truly solved, and each variation of the issue is completely unique (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 162, p. 164). Its ambiguity means it is removed from its specific situation and time; therefore it allows room for slow implementation, which is again essential to maintenance infrastructures because there is little room for radical change (Ukeles, 1969, p. 2). If a product was being created instead of knowledge this would not work. Creating a product is akin to the design description in the table above, specifically fixed in one location and time, this makes it difficult for others to replicate or use in anyway. Within the context of my work making something which does not need to be implemented immediately and can be used by other public history institutions is more suitable than making a product which cannot even be tested properly. By not having to do thorough testing of a product RtD can help avoid breaking the maintenance infrastructure. However, RtD still requires some form of simultaneous problem and solution development which by nature of the method would require some probing of the maintenance infrastructure. By using less invasive design methods in RtD you can navigate the delicate maintenance infrastructure and still do simultaneous problem and solution development.

OHD_COL_0279 JAN CRIT PLAN ETC

Plan for January conference/crit day – Version One

The day has been split into two halves. The first half will be more orientated towards the National Trust and any other public history institutions, while the second half is more focused on how to innovate and design solutions for maintaining archives. Both sessions will be online and will be recorded. I will also use a virtual whiteboard to document ideas, questions, and thoughts from the participants.

Morning Session – Oral history at the National Trust

Aim:

The general aim of this session to inform participants on the current status of oral history at the National Trust and to get feedback on some of my work which illustrates the various elements of oral history maintenance and see how this may translate over to the collection processes and policy at the National Trust.

Starting activity:

Everyone is asked to write down what they think oral history is.

Part one: Oral history at the National Trust up to now

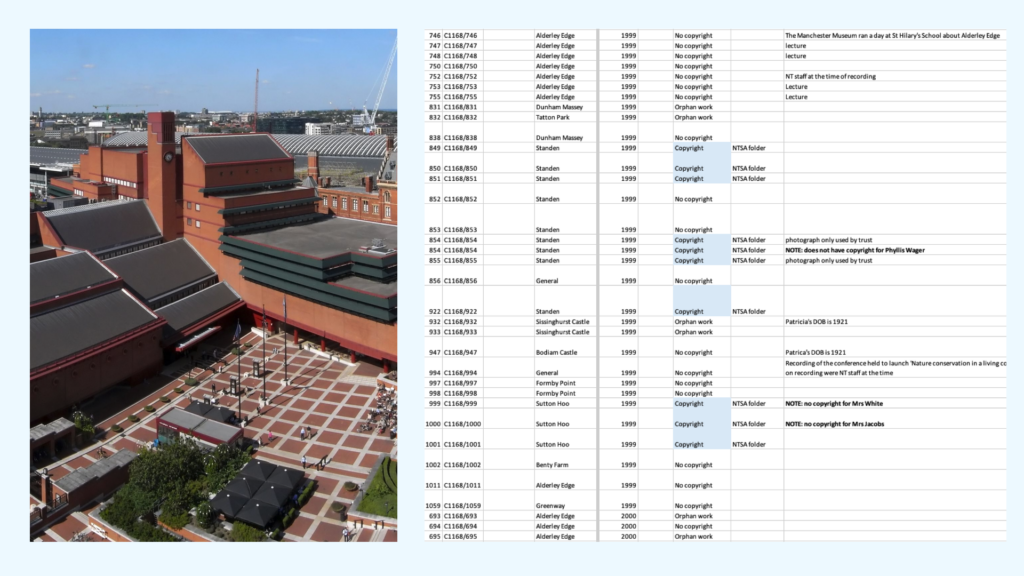

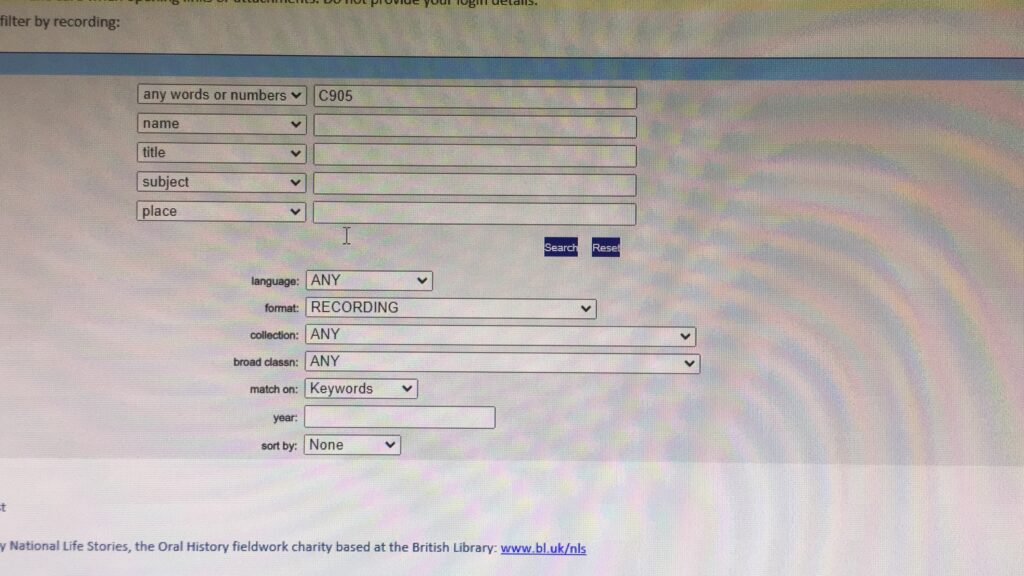

In the first part of the session we will look at the current situation of oral history at the National Trust, starting with asking the group if anyone has done or has knowledge of any oral history projects done by National Trust sites. This will be followed by me giving brief history of oral history at the National Trust and information on the National Trust sound collection at The British Library. With permission from The British Library I would like to share the spreadsheet I made during my placement and get small groups to explore the catalogue for a couple minutes. We will then end this part of the morning with a quick “brain dump” where any thoughts, questions, ideas are shared with the wider group.

Part two: The future of Oral History at the National Trust

The second part of the sessions starts with me sharing my general breakdown of what is required to maintain an oral history recording. After this the larger group is split into smaller groups again and they are asked to think how this might work within the context of the National Trust. To give the groups a bit of structure they are encouraged to think of the 5 Ws and 1 H questions (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How), then think how they might answer these questions.

Ending activity:

Everyone is asked again to write down what they think oral history is.

Afternoon Session – Innovation and design in archives

Aim:

The aim of this session is for me to share my experience and ideas of designing in archives.

The group will think about what it means for designers to work in archives but also what we mean by a “successful” or “good” archive.

Starting activity:

Everyone is asked to write down what they think an archive is.

Part One: What we learn from designer in archives?

In the first part of the session the participants are split into smaller groups which are a mixture between archivists and designers. Each group is given a scenario about maintaining access to oral history. They are then asked to think about what they would do in this particular scenario and as a group have to come with a plan. The plans are then shared in the larger group. They then go back into their smaller groups and are asked to think about whether the designers or archivists learnt anything from each other. After the smaller groups feedback again, I briefly talk about my experience of being a designer working in archives, specifically my thoughts on design and maintenance.

Part Two: What is a good archive?

Leading on from my thoughts on maintenance and design, the group is task with critically thinking what success looks like within archives. The group is first asked what they write what they think the value of archives is and are then given another scenario to discuss in their smaller groups. The scenario they are given is a world where everything can be kept and is accessible, all issues around digital obsolescence, copyright and data protection have been solved, but the climate crisis is threatening the stability of the storage systems, decay, and destruction of original material is inevitable. To give the groups some structure they are given a concepts and ideas matrix to sort their thoughts. After coming together as a big group again and feed backing, the whole group is asked whether the ideas and concepts they came up with reflect what they believe the value of archival material is.

Ending activity:

Everyone again writes what they think an archive is.

Version 2

Introduction to my PhD (General) – 15 mins

Story of the current collection PLUS values – 10 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

What value can oral history recordings give to the collections on sites? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

—————————————————— BREAK 5 mins

Issues with archiving and storing of OH at NT – 10 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

What resources do we need to make the flow from recording to archived easier? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

________________________________________ BREAK 5 mins

Legacy and knowledge transfer – 5 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

How do we make it easier to reuse oral history recordings? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

__________________________

Wrap up and thanks – 10 mins

Close

Workshop Blurb

A look into Oral History at the National Trust

Wednesday 31st Jan 2024

14:00 – 17:00

Online

This workshop is a culmination of three years of research into the past, present, and future of Oral History at the National Trust. It will take you through the stories found in the sound collection of 1700 recordings archived at The British Library, and the experience of recording Oral History on a National Trust site today. It will also offer insight into the opportunities and obstacles of recording future Oral History at the National Trust. The workshop aims to create a discourse around the rich, yet awkward resource of Oral History, how it can enrich the stories told by the National Trust, and the practical side of recording, archiving, and using such a personal artefact.

Hannah James Louwerse is completing her Collaborative Doctoral Award at Newcastle University. Her project is partnered with Seaton Delaval Hall where she has recorded oral histories from the community. She also completed a placement at The British Library auditing the National Trust’s large sound collection.

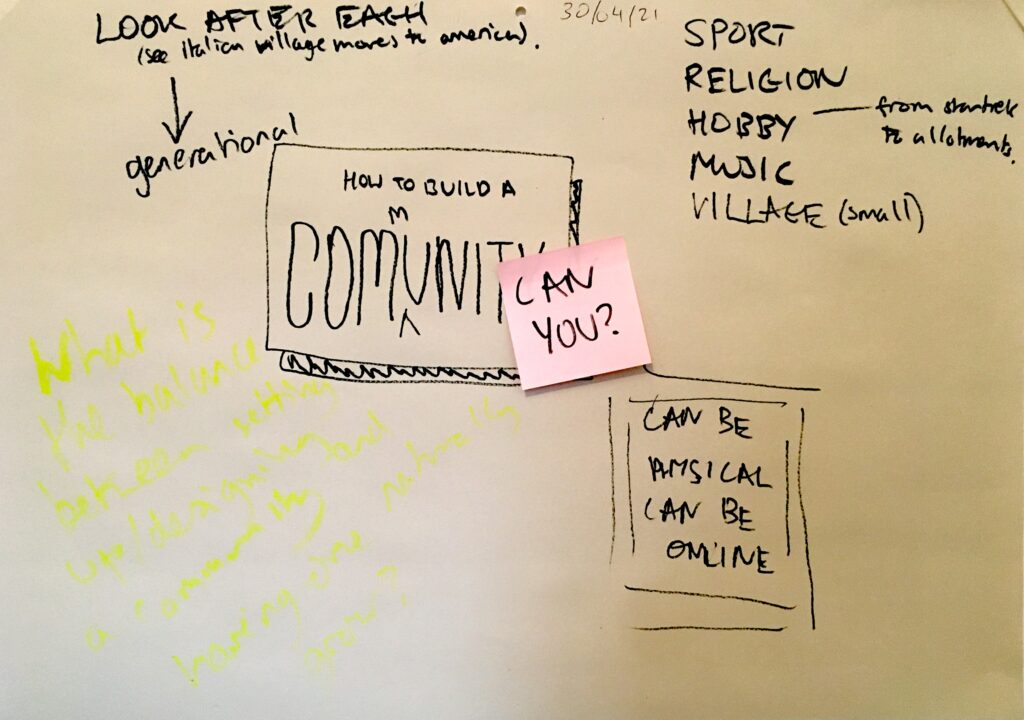

OHD_COL_0267 Photographs of PhD by Practice brainstorm

OHD_WHB_0233 Frisch and Papanek

OHD_RPT_0035 Alien in residence

OHD_PRS_0265 Reusing oral history in GLAM: a wicked problem

My PhD or CDA, collaborative doctoral award is about reusing oral history recordings within GLAM, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. I am using the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall, as a case study. Now for context my background is in Art and Design. I did Fine Art at undergrad and then moved into design, specifically innovation and system design. And so when it comes to the infamous issue of reusing oral histories I approach it from the perspective of a designer. This has led me to frame the issue as a “wicked problem”. The term “Wicked problem” comes from a paper titled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, written by a Professor of the Science of Design, Horst Rittel and a Professor of City Planning Melvin Webber in 1973. And the term has been adopted by innovators and designers because this paper is about problem solving and the act of design is basically problem solving. In the paper Rittel and Webber specifically discuss two types of problem solving: “tame and benign” problems and “wicked problems”. Tame, benign or scientific problems are simple. They are easy to define and have one simple solution. It is a very linear process: define problem, solve problem. A wicked problem is exactly the opposite. They are extremely difficult to define and coming up with one simple solution is close to impossible. And the process of solving a wicked problem is not linear at all. Defining the problem and creating solutions often happen at the same time in a kind of back forth manner. You make an initial definition of your problem and create a solution to that problem and then the testing of a solution reveals another part of the problem. So you go back to your problem definition and tweak it, and then think of another solution and it repeats. In fact, as Rittel and Webber write this process could go on forever since a wicked problem will forever keep evolving as the world changes. You can therefore never truly solve a wicked problem but only pick various interim solutions which are not perfect but will cause the least damage. And to keep creating these interim solutions you need collaboration because a single person could not possibly understand all the evolutions in the wicked problem, all the different angles, all the different stakeholders.

Therefore my project is a Collaborative Doctoral Award for a really good reason. I have benefitted greatly from being in collaboration with the National Trust because I got access to a huge variety of people who I could work with in order to build a better understanding of the problem definition and any potential solutions. And over the nearly three years I have been working on this project I have been able to expand the definition of the oral history reuse in GLAM problem. It is extremely complicated, and the specifics of my case study will not be the same as all GLAM institutions. As trait seven of wicked problem goes “every wicked problem is essentially unique”. But I have found five recurring areas of wickedness, which most GLAM institutions will have to deal with when tackling the reuse of oral history recordings: technology, labour (specially maintenance labour), money, ethics and law, and value. In order for an organisation to start understanding the wicked problem of oral history reuse and start creating solution, there needs to be a collaboration between the people who work within these five areas. Within each unique institution there will definitely be other areas and other people that need to be brought to the table but it is these five areas and the people who work in them which make up the foundation of solving the wicked problem of oral history reuse.

I am going to start with technology because this is the area which often hogs all the attention, which is not surprising, we like the technological fix, it’s sci-fi, it’s the future, it’s a bit magic. But its magic is an illusion, as Willem Schneider acknowledges in his reflection on the oral history reuse technology Project Jukebox[1]. Technology on its own will not solve the wicked problem of oral history reuse. Obsolescence has be built into technology in a near aggressive way. So while you can recruit a software engineer at the start your project to develop your technology, you are going to need someone who is able to maintain the technology when obsolescence kicks in. The area of technology is therefore completely intertwined with the area of labour, specifically maintenance labour. Maintaining a technology is not easy and the more complex a technology, the harder it is the maintain, and the more specialised person you need to hire to maintain it.

So when we think about the technology we are going to use to tackle our wicked problem, we need to always be thinking about the labour needed to maintain it. We need to collaborate with those who will maintain it and not be seduced by magic of complex technology. Because while we now have complex AI technology like ChatGPT, I can tell you from experience, and I am sure many of you can relate, in the National Trust you are using a landline to organise interview dates and posting transcripts and consent forms by snail mail. As the historian David Edgerton writes in his book The Shock of the old we should not measure technology through innovations but rather use. In which case Excel and Word are still king of the technologies.

So the technology used to help create a solution to the wicked problem of oral history reuse has to be proportional to the skills of the person maintaining it, which is why you collaborate with them. But that person and their skills will need to be paid for and so you need to talk to the money people. Economic system you are working in will directly influence your technology, because the more complex the technology, the more expertise you need, the more likely it is things are going to be a little more on the expensive side. People with advanced technological skills are not cheep. They make a lot more money shooting down bugs all day in a monster tech organisation then being the IT person in the GLAM sector. And this is not just money for a set amount of time, this is labour needed to maintain an archival object – this goes on forever. So getting feedback from the money people on any solutions you are developing your solve your wicked problem, your particular case of “how do we make oral histories reusable within my institution?”, is invaluable because the truth is money does make the world go round. So recruiting them into your little collaboration crew is essential.

Now what I have talked about so far is basically the mechanics of oral history reuse. How you use an appropriate technology to get your oral history recording from A to B from a WAV file to useable, searchable interface and keep it there. But you cannot just simply just go from A to B with oral histories. I have done three different placements for my PhD and in during all of them I was trying to make archival material reusable. I spent those six months not thinking about technology but working on either copyright, data protection, or sensitivity checks. When you are working with oral histories you are dealing with people’s lives, permissions and restrictions have to be in place in order to make it available. Which is why alongside your tech developer, your maintainer, money people, you have to have your copyright team, your data protection team, and maybe some kind of ethical review team. And again, just like obsolescence in technology collaboration is crucial because ethics changes all the time. Copyright in the form we know it now was heavily influence by the internet, which is relatively young. GDPR was only implemented in 2018. And what language and images are deemed socially acceptable is always changing. The feedback you get from the ethics people to keep your ethics up to date is so important, because most institutions in the GLAM sector cannot really afford a lawsuit or scandal, so you need to get this right.

It is getting busy our collaboration crew but have one area of wickedness left, value, and this is where things start to get really sticky, because all I have talked about so far is about making reusable oral histories not about actually reusing them. You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink. You can make your oral histories as reusable as you like but if people do not want to reuse oral histories they are not going to reuse, even if its easy to do. They have to see the value in reusing.

And this is where I mention trait 8 of wicked problems “Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem”. The difficulty of reusing oral histories is a symptom of the problem with how we value historical material. And how we value historical material is a wicked problem in itself because you can value things in so many different ways. The classic way is it monetary value. Within this frame oral histories are not going to fair to well against other historical items like chairs, paintings, original Beatles lyrics. In total I have seen the National Trust used eight different ways to value material:

Communal – The item represents a particular community.

Aesthetic importance – The item is deemed ‘aesthetically’ important or is from a famous artist.

Illustrative / historic – The item is illustrative of some historic moment.

Evidential – The item works as evidence to see how something was.

Supports Learning – The item is helpful in supporting learning found in the national curriculum.

Popular appeal – The item has mainstream appeal.

Cultural heritage significance – The item is significant to a specific culture.

Contextual Significance – The item gives important contextual information to a site, or a historical event

Materials also have international, national, regional or local value.

You can also flip the idea of value, how much is it going to cost to keep this item? This can again be measured several ways for example money and space, but also carbon. How much energy will it take to keep this item? Yep the reusing of oral history is an environmental issue.

Value is complicated and in order to get people to reuse oral histories we need to understand all the value oral histories can offer. We need to talk to curators, artists, educators, community workers, academics, all the potential different reusers and ask them what they find valuable. Why would they reuse oral history? And then we need to think about how we communicate this value. Do we go top down and work with policy makers to develop policy which makes it a requirement to reuse oral histories? Or do we work bottom up and try and nurture a culture of oral history reuse by teaching it more at a university level and creating projects based around reuse? Although whether a project based solely around reuse will get funding is another question, which brings us back to the money people and proves the wicked entanglement of it all.

This is not a banal, tame problem. It is a wicked problem – a mess. These five areas, well four overlapping` areas and a continent of complexity, are deeply intertwined and this is before we even start bringing in the unique elements of each individual institutions case of oral history reuse. And the only way to start detangling in some way without failing or being destructive is by collaborating and create a solution that will bring us a step closer to reusing oral history.

[1] “we stumbled onto digital technology for oral history under the false assumption that it would save us money and personnel in the long run.” (p. 19)

OHD_WRT_0264 Why a PhD by Practice

Design is not an island

Every week or so I spend three hours standing in an 18th century hall. No one has asked me to do this, not my university or the hall, which is the partner institution within my Collaborative Doctoral Award. And yet, I do this because it is an essential part of my research. It is essential because the central issue of my research project is looking to solve the problem of the so-called “deep dark secret of oral history;” the sad reality that oral history recordings rarely get used once archived (Frisch, 2008). My work is specifically looking at how oral history recordings can be reused on heritage sites. This is not an easy problem to solve, in fact it is not an easy problem to define. It is what is referred to in the design world as a “wicked problem”, an extremely complex and ever-changing problem, which can be viewed from different perspectives, conjuring up different solutions (Rittel and Webber, 1973; Buchanan, 1992). In design the defining of a wicked problem and the testing of solutions happens simultaneously (Buchanan, 1992; Bailey et al., 2019). During this process the designer, the one creating solutions, needs to be deeply reflective. In the context of this project I play the role of the designer. My PhD is a PhD by Practice and standing in a hall is part of my process to define the problem and find a solution to the issue of the limited reuse of oral history recordings. This but a brief explanation to why I am standing in a hall, so let us take a couple of steps back to fully unpack why I am doing a PhD by Practice. We must start by understanding what a “wicked problem” is and where it came from, then we can look at the methods used to define and solve these wicked problems.

The rise of the swampy lowlands

We start around the middle of the Cold War, where there a significant “anti-professionals” movement underway and the professionals in question are going through a crisis of confidence. The term “professionals” is used by Horst W. J. Rittel, who coined the term “wicked problem”, and the philosopher Donald A. Schön, who wrote The Reflective Practitioner, to refer to practice based subjects which often quite some form of formal training, such as lawyers, doctors, engineers, police, and teachers. (Schön, 2016, p. 3; Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 155). Neither Rittel or Schön discuss designers specifically, however designers would fall under the same umbrella as many designers first go to design school before they moved into practice. It was these professionals, who were going through a crisis in confidence because it seemed they were struggling to solve many of society’s problems. Rittel and Webber list the various areas where the public were becoming dissatisfied with the professionals work such as; the education system, urban development, the police. The issue which comes up in both Rittel and Webber’s piece and Schön’s book is the Vietnam War which was as Schön describes “a professionally conceived and managed war [which] has been widely perceived as a national disaster.” (Schön, 2016, p. 4). All these events and issues demonstrated to the public how the actions of professionals can have negative and even devastating consequences for differents groups of people in different ways (Schön, 2016, p. 4). Both Rittel and Webber, and Schön attribute the negative consequences of professionals’ actions to a mismatch between the society’s problems and the professionals’ approach to solving these problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156; Schön, 2016, p.14). In particular it was their nineteenth century “Newtonian” and “Positivists” approach to problem solving, which no longer seemed to work on these twentieth century problems. Their approach was distinctly linear; define problem and then solve it (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156; Schön, 2016, p. 39; Buchanan, 1992, p. 15). And while this approach works well when solving a mathematical problem or deciding a move in chess, it does not work when solving complicated problems. For example with the Vietnam war this linear approach resulted in the problem being simplified into “stop the spread of Communism” and the solution being reduced to “fight war with communists using chemical weapons”. We all know this did not work and the Vietnam War went on to become one of the biggest disasters in American military history. The war and other events made people think the professionals were no longer suitable to solve society’s problems, however Rittel and Webber and Schön argue this was due to their linear approach to problem solving not their lack of knowledge.

Rittel and Webber seem to at first attribute failures of linear problem solving to problems like the Vietnam War being simply harder to solve than the “definable, understandable and consensual” problems the professionals were working with straight after the Second World War (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156). This would imply the problems dealt with after the Second World War were simple, like a mathematical equation. Although possible, we must also consider how there instead was a shift in how we view of problems and the structure of society as a whole, especially when we contemplate how philosophical schools of thought, such as Post-structuralism, were being developed around the same as Rittel and Webber were writing. While neither Rittel and Webber or Schön make direct references to the Post-structulaist movement, there are parallels between Rittel and Webber’s ideas and language, and the ideas and language found in the literature of the Post-structuralist movement. For example, in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia published in 1980, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the psychoanalyst Félix Guattari they outlined the idea of rhizomatic thought, i.e. the idea that everything is connected through complex non-linear networks, rather than some form of linear hierarchy. Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of the Rhizome, and Rittel and Webber’s idea of the “wicked problem” are both proposed in opposition to the more Positivists and Newtonian linear way of thinking about society (Buchanan, 1999, p. 15; Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p. 7). There are similarities in the language Rittel and Webber, and Schön used to describe these complex problems and the language Deleuze and Guattari used to communicate the nature of the Rhizome. For example, Rittel and Webber explain why they specifically use the term “wicked”:

We use the term “wicked” in a meaning akin to that of “malignant” (in contrast to “benign”) or “vicious” (like a circle) or “tricky” (like a leprechaun) or “aggressive” (like a lion, in contrast to the docility of a lamb). (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 160)

Along similar lines Schön refers to these problems as a “tangled web” or “a swampy lowland where situations are confusing “messes”” (Schön, 2016, p. 42). While Deleuze and Guattari write how “A rhizome [ceaselessly] establishes connections between semiotic chains, organisations of power, and circumstances” and talk about a rhizome’s complete lack of unity (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p. 8).

While conscious or not of the parallels between their ideas and the Post-Structuralist’s, it is Rittel and Webber, and Schön’s application of these Post-structuralist(-like) ideas which it useful to designers and other problem solvers, and became a corner stone idea of design thinking (Buchanan, 1992). They used the ideas of webs, networks and relationships to adjust two elements of problem solving: the overal aim of the process and the order in which things are done. Rittel and Webber, and Schön all write how within the old linear method of problem solving the main aim was to come up with a solution, and therefore less time was spent defining the problem. They wished to shift this focus to make the defining of the problem equal to (if not more important) than creating a solution (Schön, 2016, p. 40; Rittel and Webber, 1973). In addition, Rittel and Webber, and Schön all wished to abandon the idea of these linear steps in problem solving and instead have the problem definition and problem solution occur simultaneously, having each inform developments in the other (Buchanan, 1999. p. 15; Schön, 2016, p. 40). It is this latter change they propose which needs some further explanation to see why simultaneous problem definition and problem solution is vital to solving problems and untangling these wicked messes.

Understanding the web

Before we dive head first into simultaneous problem definition and problem solution we need to understand the structure of problems and why this makes them difficult to define. The wicked problem is one of many ways to describes complex problems, however there are other metaphors we can draw on. Near the end of the twentieth century you have the metaphor of “infrastructures” used by sociologist Susan Leigh Star to describe human relationships with technology and computer networks (Star, 1999), and designers have use the idea of designs living within wider eco systems to articulate the environmental impact of design products (Manzini and Cullars, 1992; Tonkinwise, 2014). All of these work as metaphors to help us understand the structure of the problems society is dealing with, and so to avoid confusion I will from now on just used the term “problem structure” and not wicked problem or rhizome or infrastructure or swampy mess. While problem structures are able to go by many names, there are four main traits problem structures have which are found across these different texts .

1. Problems are subjective

Since the linear format of problem solving spent little time on defining the problem/understanding the problem structure, it also did not consider the subjective nature of problem definition. The more Post-structulaist way of thinking about problems recognises how subjective our view of a problem structure can be (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161). The problem structure is not a single person’s view on an issue but a collection of many people’s collective experience of an issue woven together into a web-like or, as Deleuze and Guattari would call it, rhizomatic structure. The sociologist Susan Leigh Star uses the example of a flight of stairs to illustrate the subjective nature of issues. A flight of stairs is to the majority of people a path from upstairs to downstairs or vice versa, however for a person in a wheelchair stairs are seen as as obstacle (Star, 1999, p. 380). You can expand this even further to cleaners finding stairs more difficult to clean than a flat surface or an architect wishing for a certain aesthetic style in the stairs or the builder who has to construct and later maintain the stairs or the person who has to source and pay for the materials used to make the stairs. Every single one of these views on stairs can be brought together to create the rhizomatic understanding of the stairs. By recognising the problem structure is made up of these subjective experiences the person tasked with problem solving is able to get a better understanding of the problem structure, ensuring they do not generate a solution based on a single narrative.

2. Problems are part of other problems

However, the borders of the problem structure do not end with people’s view and experience of the central issue you were looking at, as Rittel and Webber say “Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem”. Problem solving will start on one level, “crime on the street is a problem” and then move to higher levels, for example a general lack of opportunity, high poverty, or moral decay (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 165). This is similar to one of the properties of Leigh Star’s idea of infrastructure – “embeddedness,” which describes how an “infrastructure is sunk into and inside of other structures, social arrangements, and technologies” (Star, 1999, p. 381). A problem should therefore not be seen as an isolated issue but something connected and part of various other issues within wider society.

3. Problems are do not stand still

Problem structures are not static and will change over time. Deleuze and Guattari describe how “a rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p.10). Within the context of problem solving this shattering and restarting means a problem structure is always evolving, which in turn means a solution offered at one time may no longer be appropriate further down the line.

These first three traits of problem structures are why solving problems without proper problem definition can be destructive. To start with problem solving is already inherently a destructive act. The design theorist Cameron Tonkinwise explains how “innovation is itself a deliberate act of destroying some aspect of current existence” (Tonkinwise, 2014, p. 201). Through problem solving the current existence is remoulded, new things are added and other things are taken away until a new order of things has been achieved (Tonkinwise, 2014, p. 201; Papanek, 2020, p. 3). It is sometimes necessary to destroy things, but when this destruction does not take into consideration the wider problem structure of the central issue the destruction can have ripple effects across the entire structure. It is therefore essential to identify the structure you are creating in and knowing to some degree what effect any intervention might have across the entire structure. As Rittel and Webber say:

It becomes morally objectionable for the planner to treat a wicked problem as though it were a tame one, or to tame a wicked problem prematurely, or to refuse to recognize the inherent wickedness of social problems. (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161)

The destructive nature of problem solving means one needs to be extremely cautious. Knowing exactly what to propose, create, or design is key and it depends on your knowledge of the problem. And this is where the fourth trait of problems comes in, and when things start to get very tricky.

4. Problems are invisible

Parts of problem structures are invisible because they only become visible through some form of articulation. For example, with the first and second trait, problems are subjective and part of other problems, you are only able to see the parts of the problem structure you have researched through either observation or articulation from either yourself or someone else. If you do not talk to all the people involved there will be parts of the problem structure which is missing. Sometimes this is not you fault as Leigh Star points out centre topics “tend to be squirrelled away in semi-private settings” (Star, 1999, p. 378). Or you simple ran out of time, money, or patience before you could uncover the problem structure (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 162). When it comes to the third trait, problems do not stand still, there are parts of the problem’s network which do not yet exist and are therefore invisible.

There are also parts of the problem structure which are invisible unless under two circumstances, breakdown and probing. The first, Leigh Star lists as one of the properties of infrastructures, “invisible unless broken”. What Leigh Star specifically refers to here is types of maintenance structures, which society assumes will always work until they do not (Star, 1999, p. 382). Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift in, Out of order: Understanding repair and maintenance, describe this phenomenon as follow:

The sudden absence of infrastructural flow creates visibility, just as the continued, normalized use of infrastructures creates a deep taken-for-grantedness and invisibility. (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 8)

Any breakdown of a problem structure could reveal elements of the structure which were previously invisible. The other circumstance when elements of the problem structure becomes visible is when is it probed. This specific action of probing in order to make visible is the main motivation to do problem definition and problem solution simultaneously (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 161). In their paper Rittel and Webber demostate this process on the “poverty problem”, where they first ask question “Does poverty mean low income?” and then work out what the determinants are for low-income through further questioning and answering (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161). Every question is part of problem definition and every answer is part of problem solution, but both help build the problem structure. Each question is a probe which provokes an answer which makes visible more of the problem structure. Probes can take on different formats which I will expand on in the following section.

To summarise the four main traits of a problem structure are how it is: a collection of subjective narratives, connected to other problems, and always changing, and then an overarching fourth trait of general invisibility unless broken or probed. Recognising these four traits of a problem structure lays the foundation of simultaneous problem definiton and solution. can help in both problem definition and problem solution. The next step is to start building the problem structure and maybe find some .

The practical bit

Schön wanted to make clear the crisis in confidence professionals were experiencing during the Cold War and the anti-professional movement was due to the application of professional knowledge not the knowledge itself (Schön, 2016, p. 49). The linear method of problem solving did not allow for the complexity found in (modern) problem structures. However, Schön offers an alternative method which can handle the complexity of problem structures – “knowing-in-action.” Knowing-in-action is that tacit knowledge we gain from doing things and has the following properties:

- There are actions, recognitions, and judgements which we know how to carry out spontaneously; we do not have to think about them prior to or during their performance

- We are often unaware of having learned to do these things; we simply find ourselves doing them

- In some cases, we were once aware of the understandings which were subsequently internalised in our feeling for the stuff of action. In other cases, we may never have been aware of them. In both cases, however, we are usually unable to describe the knowing which our actions reveals (Schön, 2016, p. 54)

Schön backs this up it with the idea of common sense being the expression of “know-how,” specifically through action, “a tight-rope walker’s know-how, for example, lies in, and is revealed by, the way he takes his trip across the wire” (Schön, 2016, p. 50). Common sense also proves Schön’s second mode of thinking, “reflection-in-action.” While knowing-in-action is about doing, reflection-in-action is doing and thinking about it (Schön, 2016, p. 54). The example he uses is a study where children were asked to balance blocks which were unevenly weighted. The children knew how the balance point would likely be the visual centre. However, this knowledge failed them when balancing the unevenly weighted blocks. Eventually after trying and testing different balancing points on the blocks, the children understood the balancing point of the blocks was not always the visual centre, but depended of the weight distribution. They then starting weighing the blocks beforehand to feel how the weight is distributed and found the correct balancing point based off this knowledge (Schön, 2016, p. 57). So the children, without being taught, learnt the balancing point depends on weight distribution, and not the visual centre. Schön summarises the results of reflection-in-action as follows:

When someone reflects-in-action, he becomes a research in the practice context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. (Schön, 2016, p. 68).

This creating a “new theory” for a “unique case” is exactly what simultaneous problem definition and problem solution is. Therefore the term “unique case” can easily be replaced by rhizome, wicked problem, or problem structure, each of which describe unique, ever-changing situations. If we look back at how Rittel and Webber described the process of simultaneous problem definition and problem solution through the example of the poverty problem, you can clearly see how reflection-in-action fits this process. It is a constant loop of testing theories and then returning to the drawing board and then back again – altering the theory and getting a better understanding of the case.

In addition to being a method of simultaneous problem definition and problem solving, reflection-in-action also creates good client relationships. A person who practices reflection-in-action or a reflective practitioner is meant to develop, according to Schön, a very different tone of relationship in comparison to a professional who describes themselves as an “expert” and uses the older linear method of problem solving. The main difference is how a reflective practitioner, although aware they have expert knowledge, also understands this knowledge makes up only part of the problem structure. The rest of the knowledge is found with their clients.1 The term client is used here to mean anyone who comes into contact with the problem and solution. For example within the context of the stairs the cleaner, non-disable user, disable user, builder, materials supplier should all be consider clients. The relationship the reflective practitioner has with their clients is also distinctively more open and honest than, what Schön refers to as, the “Expert”. Where the Reflective Practitioner drops the professional façade in order to create a more free, honest, and open relationship with their clients, including articulating their uncertainties, the Expert prefers to keep their uncertainties hidden, and have a professional distance between them and the clients, while also conveying “a feeling of warmth and sympathy as a “sweetener”” (Schön, 2016, p. 300). The good client relationship the Reflective Practitioner is able to nurture results in a richer exchange of information between the practitioner and the client. In addition the client is also more likely to accept and/or challenge the solutions the practitioner offers (Schön, 2016, p. 302). Both of these results are essential for simultaneous problem definition and problem solution, as you need information to uncover the problem structure, and also have permission to probe the problem structure with possible solutions.

So why are you standing in a hall?

I am standing in an 18th century hall because the issue of the reusing of oral history recordings, especially the reuse of recordings on heritage sites, is a very complex or wicked problem. It is rhizomatic, made up of many peoples subjective view on the issue of handing and reusing oral history recordings, such as the original interviewers, the archivists, the site’s volunteers, and the site’s staff. It is entwined into other issues, for example digital obsolescence, data management, the environmental impact of digital files, and how we value within heritage. It is also constantly moving and changing as I am researching, because it is part of an operating organisation. There are also many parts which are still invisible to me because their access is restricted in some way, again due to me working with an operating organisation. Above all a lot of what I am researching falls under maintenance work, the system which Susan Leigh Star identified as being intrinsically invisible. Because the issue of reusing oral history recordings has all the elements of a complicated problem structure, I cannot solve the problem through the linear method and have to use the techniques of Rittel and Webber discuss and become a Reflective Practitioner practicing reflection-in-action. This action has lead me to standing in the hall, because I started volunteering at the hall and also did a placement at the hall, both of which allowed me to understand numerous things about the problem structure. For example, how staff members can be suddenly assigned carpark duty and have to leave all the work they planned to do that day by the wayside, or the complicated and delicate power dynamics between the volunteers and the staff, or simply how the IT systems work, or do not work. If I was not doing a PhD by Practice it would be unlikely I would have known these things about the problem I am trying to find a solution for. And as so many I have mentioned point out developing a solution when you do not know the problem can be considered unethical.

1 Schön does specify “stakeholders” and “constituents” are used instead of “client” when dealing with multiple groups (Schön, 2016, p. 291). However, I prefer the term client because I feel it communicates the power structure of the relationship better: I am the designer/problem solving serving my clients. I am working for them, they are not working or me.

OHD_DSF_0224 A graph mapping fictional designs

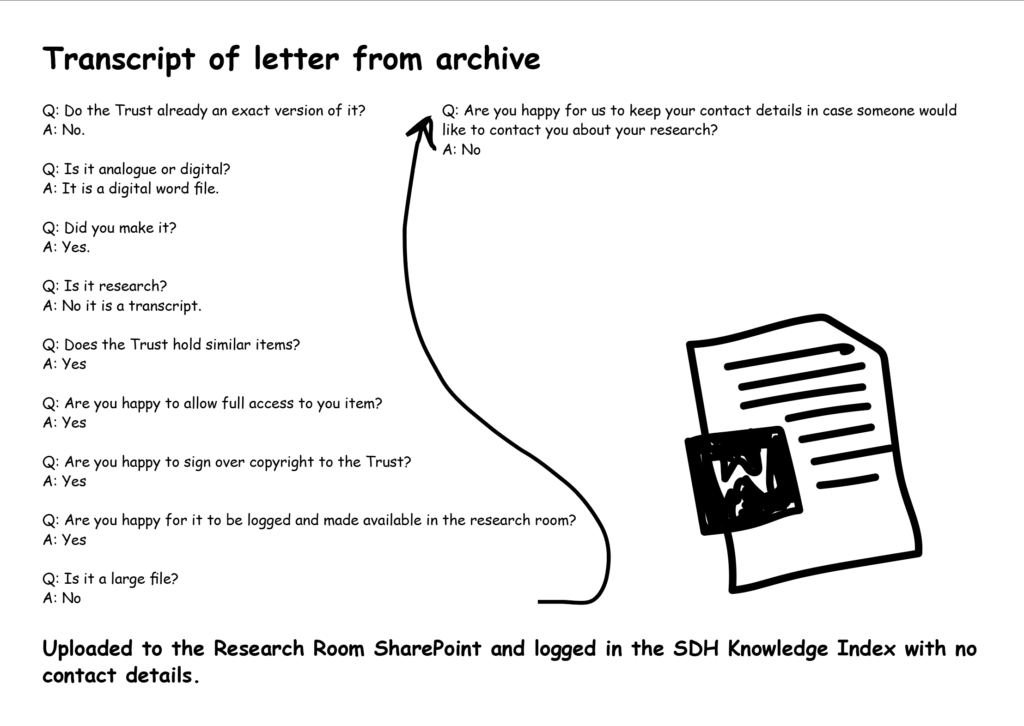

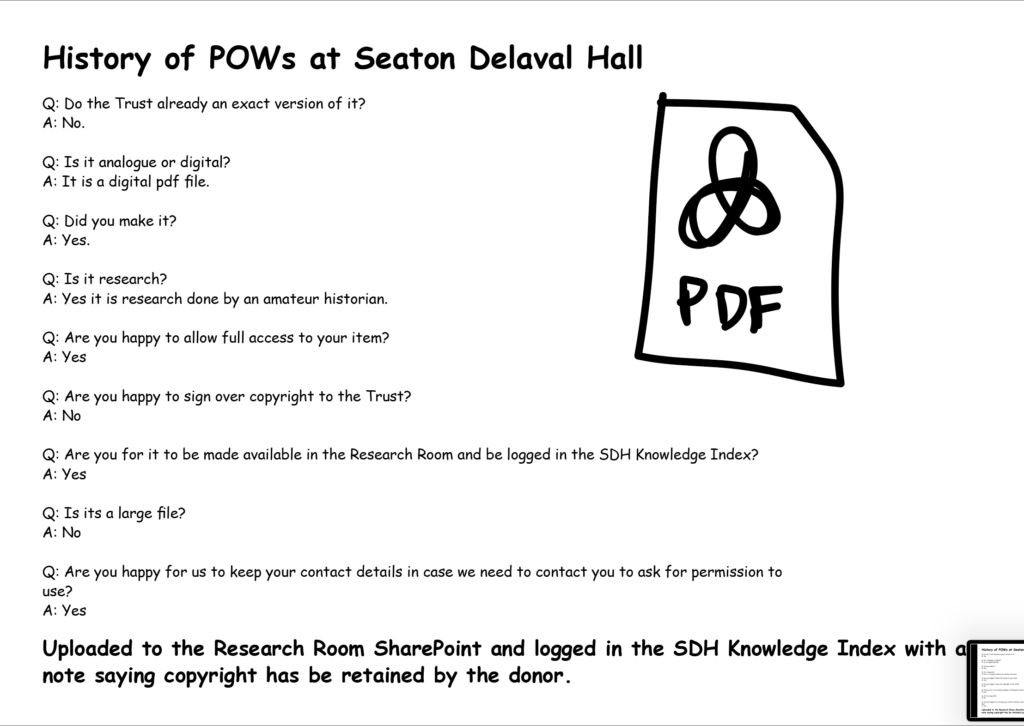

OHD_PRT_0188 Testing the Research Room flowchart

OHD_PRS_0185 Presentation for Jo and Heather

OHD_DSF_0184 Oral history at the hall design project

OHD_DSF_0182 Design Fiction Research Room

OHD_DSF_0173 Interim Design Fiction

OHD_WRT_0172 Chpt. 01 History of oral history tech

Chpt. 01 – The History of Oral History Technology

“The history of progress is littered with experimental failures.”

– Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World

Let is take a moment to contemplate the MiniDisc. Developed by Sony in 1992, it was meant to replace the cassette, with its ability to edit and rewrite recordings, and 60 – 80 minutes audio storage, it was the hot new thing that was going to change how we record forever. Fast forward thirty years or so and the MiniDisc has become one of the textbook examples of a failed technology. For oral historians and sound archivists the promises made by the Minidisc were never fulfilled but for different reasons. For oral historians it was difficult to use when recording, and for sound archivists it was incompatible with certain editing and storage softwares, and sharing files was not universally possible (Perks, 2012). Today there still is a disconnect between what oral historians want from technology, what sound archivists want from technology, and what the technology actually offers. It is a three-way relationship where no one is completely satisfied. Oral historians wish technology to provide them with the tools to better contextualise their archived oral history recordings and utilise the orality of oral history recordings, even though oral historians have heavily relied on transcripts for years (Boyd, 2014; Frisch 2008). Archivists simply want a technology that will last and ensure access for many, many years to come (Perks, 2012). Technology however does not exclusively cater to oral historians and sound archivists, but supplies far more lucrative fields and is therefore more likely to bend to their needs and desires (Perks, 2012). This means there is a gap in the market for technology that satisfies oral historians and archivists. Over the years there have been several attempts to fill this gap. I say attempts because no one technology has completely fulfilled oral historians and sound archivists wishes, some are very close but complete adoption has not yet been achieved. To some extend this is due to people having their fingers burnt too many times, I refer back to the Minidisc. Alongside the differing needs of oral historians and archivists, there is the tension between the techno-enthusiasts and the techno-phobes. While some oral historians, like Michael Frisch greet the technological age with much enthusiasm others, like Al Thomson have taken a slightly more cautious approach (Frisch, 2008; Lambert and Frisch, 2013; Thomson, 2007). Although truth be told it is difficult to constantly be aware of people’s feelings towards technology as it is so rapidly evolving. When Al Thompson wrote about about the digital revolution in Four Paradigm Transformations in Oral History, Youtube was only two years old and social media sites were not as prominent as they are now. Rob Perks wrote Messiah with the Microphone before the huge revelations around the NSA and GCHQ surveillance in 2013 and the Cambridge Analytica scandal post-2016. Not to mention the colossal impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on both the fields of oral history and archiving and their relationship with technology.

Nevertheless, taking all of this in my stride, in this chapter I wish to explore the attempts made to find a technological solution to the problem of archived oral history recordings as my project makes up part of this bumpy ride. I wish to take a moment to reflect on the history of oral history technology, investigating what has happen so far and what I can learn from my predecessors. Above all what I am looking at is why they failed. At face valued this seems cruel but in reality any story about innovation is a story about failure (Syed, 2020, p.43; Papanek, 200, p. 184). The trick is to look failure in the face, something designers are repeated credited being good at (Syed, 2020; Kelly and Kelly, 2013). So that is what I am going to do. I, a designer, am going to visit my ancestors, the endeavours that sadly failed, and my elders, those who are still battling away. I shall pay my respect, listen to their stories and warnings, and build the foundation of this project. My journey starts with a visit to the graveyard of oral history technology.

Welcome to the graveyard

The oldest plot in the graveyard of oral history technology belongs the TAPE system. A system devised by Dale Treleven in 1981 at the Wisconsin State Historical Society, that encouraged users to access oral history tapes in a way that puts ‘orality’ at its centre. Naturally it was deemed to much and not shiny enough (Boyd, 2014). The second oldest and rather grander plot belongs to Project Jukebox. Developed at the University of Alaska Fairbanks at the start of the nineties it was described as “a fantastic jump into space age technology” (Lake, 1991, p. 30). However according to Willam Schneider, one of the developers, it was more like a “stumble” into digital technology with the naive hope that it would save time and money (Schneider, 2014). There is mention of CDs, dial-up technology, and software support provided by a corporation they refer to as Apple Computers Inc. (Lake, 1991; Smith, 1991). Project Jukebox did not fully make it out of the twentieth century, but it definitely started trend. Next to Project Jukebox lies the grave of the Visual Oral/Aural History Archive or VOAHA. Sherna Berger Gluck at California State University, Long Beach was deeply inspired by Project Jukebox during the creation of VOAHA, specifically their approach to ethical concerns surrounding sharing oral history recordings and its ‘boutique’ nature (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014). Although this time there was a focus on ensuring that it was better connected to the web, we were after all at the turn of the millennium and the internet was getting big. Eventually both Project Jukebox and VOAHA became victims of the seemingly inevitable technological advancements and university budget cuts, however both are also survived by their ‘children’. The former has a version available online and the latter was absorbed into the university library system, not without some hiccups (Gluck, 2014).

Beside these two juggernauts of projects the graveyard is filled with similar endeavours, mostly websites copying the ‘boutique’ style interface, which remained largely the same only slight altering to fit wider developments in digital aesthetics (Boyd, 2014). An example of such website was the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database developed by Doug Boyd, which in his words was a “gorgeous” website that had “logical” information architecture. However, the requirements to achieve this ‘boutique’ style every time a new recording was added were too high for these larger scale oral history projects, making ventures like Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, Project Jukebox and VOAHA, more akin to well curated exhibitions than oral history archives (Boyd, 2014, p. 89). Another project, Montreal Life Stories, established at Concordia University seemed to whole heartedly embrace this digital exhibition format. Steven High writes how digital storytelling, using digital software to blend together various mediums into a narrative experience for a viewer, became key in ensuring better community participation in the Life Stories project (High, 2010). Sadly, although no surprising, www.lifestoriesmontreal.ca no longer links to the original project. When reflecting on Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database Boyd admits this focus on the userbility led to a lack of consideration for the maintenance required to keep his website running. In the end it was “digitally abandoned, opened up to online hackers and eventually taken down” (2014, p. 9). Just like Project Jukebox and VOAHA, the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database is survived by a comparable version on the web today. I am of course unable to compare the two, however the project’s kin does seem to crudely jump between host websites and insist on opening a new tab every time. Nevertheless the same cannot be said for many of the project’s comrades which leave nothing behind bar a trail of dead links.