JOSH SHEEHY (AUTHOR) AND MAX CHAU (CO-AUTHOR)

On 7 October 2021, a consortium backed by the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) purchased Newcastle United for £305m. Fans were rightfully overjoyed that the more than decade long austerity under Mike Ashley was coming to an end, bringing new hope for success that could be felt and seen across the city. But the takeover was important for more than just football fans. Human rights advocates were far less jubilant, labelling the takeover as the latest instance of ‘sportswashing’.

This blog post considers whether newly proposed measures in the Fan-Led Review of Football Governance will be sufficient to prevent sportswashing in the future and outlines additional measures that the government should consider if it intends to tackle football’s proximity to human rights abuses more comprehensively.

Saudi Arabia’s Human Rights Abuses

For decades, Saudi Arabia has been accused of significant human rights breaches, which few feel it has been held accountable for. Most famously, in 2018 Saudi Arabia was accused of the extrajudicial killing of journalist and political dissident Jamal Khashoggi. CIA reports found he was assassinated in the Saudi Consulate in Turkey with the subsequent closed trial deemed to lack credibility and transparency. However, Khashoggi’s murder is only the tip of the human rights violation iceberg. Saudi Arabia’s disregard for freedom of expression, association and belief is broad, continuing to imprison women’s rights activists, peaceful protesters and gay rights activists on vague and obfuscating charges to this day.

Further violations arise out of Saudi involvement in the armed conflict in Yemen. Since March 2015, Human Rights Watch has documented numerous unlawful attacks by the Saudi-led coalition that have hit homes, markets, hospitals, schools, and mosques; some of which may amount to war crimes. Additionally, their sustained blockade of ports has limited international humanitarian aid efforts from providing life-saving supplies to the suffering Yemini population.

Mohammed bin Salman and the PIF

While evidently severe, it is quite fair for Newcastle United fans to question how these human rights violations – thousands of miles away – relate to their club. After all, the purchase of the club was led by the PIF, a corporation, rather than the Saudi State. During negotiations, the English Premier League (EPL) raised this question, unsure over which entities would own or have the ability to control the club following the takeover.

In response, the PIF offered ‘legally binding assurances’ that the PIF and Saudi State were (and shall remain) independent, sufficient to abate the EPL’s concern. However, critics are rightfully unsure of the substance of these assurances. Mohammed bin Salman remains simultaneously the head of state for Saudi Arabia and the Chairman of the PIF, making any real separation of interest or decision-making improbable.

Furthermore, regardless of legal assurances, Mohammed bin Salman has been personally implicated in several human rights abuses, making the PIF proximate to human rights abuse irrespective of its connection to the Saudi state. Supporting evidence includes documents released by the CIA that indicate Bin Salman had personally approved the killing of Jamal Khashoggi within the Saudi Consulate in Turkey as well as an admission he was responsible for the murder in part.

What is ‘sportswashing’?

Consequently, with the connection of Newcastle United’s new owners to human rights abuses so proximate, the labelling of the takeover as ‘sportswashing’ may not be entirely unjustified; but what is sportswashing?

Most simply, ‘sportswashing’ is the practice of using sport to improve a tarnished reputation. It has been used as a reputational tool throughout history, most famously in the Berlin Summer Olympics of 1936 and, more recently, as an alleged reason for China hosting the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. It can work in multiple ways, either by diverting attention away from certain events or information, by normalising the public to irreputable parties, or by transferring the reputation of one well-regarded party onto another.

Whether Saudi Arabia set out to improve its reputation by purchasing Newcastle United is only speculation but there is some evidence it has worked, at least locally, with Newcastle fans choosing to wear traditional Saudi dress throughout the season. Though clearly confined to a minority of supporters, should Newcastle begin to garner more success domestically and internationally, that admiration for Saudi Arabia will only grow with the club’s renown.

Fan-Led Review of English Football Governance

The question then, is whether it is acceptable for people with human rights records such as bin Salman to be involved in English sport. If not, what can be done about it? The solution may lie in the proposals set forth in the Fan-Led Review of Football Governance. It comes after the collapse of Bury FC in 2019, the Covid-19 financial crisis, and the attempt to set up a European Super League (ESL) in April 2021. However, despite being written before issues surrounding the Saudi takeover were known, its recommendations offer an avenue to integrate human rights values into English football securely and with force. Foundationally, this involves the establishment of a new Independent Regulator for English Football (IREF).

What is the IREF?

The primary role of the IREF would be to establish and maintain a licencing system for professional men’s football clubs predicated on powers bestowed by an Act of Parliament. This would require clubs to meet the requirements of its licensing agreement or else face having their licence to participate in English football removed. In this way, the IREF would have a mechanism to enforce its objectives on clubs whilst providing them sufficient flexibility to adapt and tailor new requirements according to new problems that arise.

Enabling this, the IREF would be given strong investigatory powers, including the ability to demand information from clubs, assess compliance and use interim powers for suspected license breaches pending investigation. Furthermore, the IREF would have a range of sanctions including: the ability to order compliance, ordering compensation, reputational sanctions (i.e. naming and shaming), fines, points deductions and transfer bans. Most significantly, the IREF would be able to sanction owners and directors of clubs individually, including the capacity to ban them from English football entirely. At its most extreme, this could involve temporary administration of the club by an IREF-appointed director until a new owner is found.

What are its objectives?

Evidently the IREF would have sufficient power to implement its objectives, but the precise scope of these objectives remains unclear. Under the present review, these will be focused on ensuring financial sustainability and improving decision-making at clubs through a new corporate governance code, as well as measures to improve diversity and supporter engagement. Though the current proposals set forth by the fan-led review do not expressly mention human rights, fundamentally, it premises the creation of the IREF on supporting the long-term health of English football. Therefore, given the considerable media attention and vocal concern from club’s themselves for the financial and reputational damage that association with human rights abuses could have, it is likely that the IREF will at least consider measures to combat potential problems. Additionally, interest groups including Our Beautiful Game, FA Equality Now and Fair Game were consulted in the process of formulating the review, making it clear that there is a place for moral value propositions to be heard and enforced through the IREF.

Ownership and Directors Test

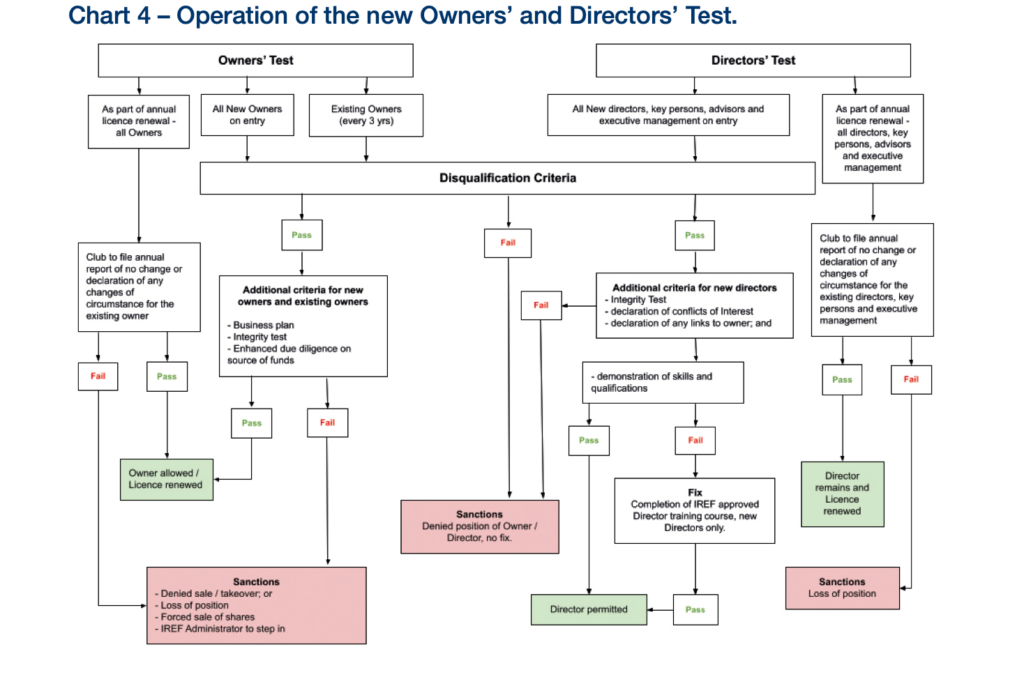

Of the 47 recommendations made in the review, proposed changes to the ownership and directors tests across all leagues could tackle the involvement of human rights abusers in football most effectively.

Existing Tests

Presently, there are three different Owners’ and Directors’ Tests across the hierarchy of leagues within English football, administered by the EPL, EFL and FA respectively. Though varied, the three tests in operation today cover broad, objective factors that disqualify individuals from being an owner or director of a football club in line with the Companies Act 2006.

These include past involvement with club bankruptcies, dishonest dealings with football authorities, control or influence at multiple clubs, criminal convictions (including overseas), personal insolvencies, suspension or ban from another sport, being barred from entry to the UK, and being a football agent. Importantly, they do not capture wrongs beyond the sphere of finances or football such as human rights abuses, that could nevertheless cause financial and reputational harm to their club or English football. The creation of the IREF offers the opportunity to introduce a new unified test with a broader and more meaningful scope to include these considerations. The fan-led review proposes a test with several stages:

The New Test

Firstly, the IREF would disqualify prospective owners and directives if they are subject to any of the disqualification criteria set out in Section F of the Premier League Handbook. These criteria are mostly limited to financial and criminal misconduct mentioned previously, forming the backbone of the narrow ownership and director’s tests as they exist currently.

Secondly, prospective owners will now also be required to:

a. Submit a business plan for assessment by IREF.

b. Provide evidence of sufficient financial resources to cover three years.

c. Be subject to enhanced due diligence checks on source of funds to be developed in accordance with the Home Office and National Crime Agency (NCA).

d. Pass an Integrity Test.

It is the final stage, the integrity test, that represents the most substantial reform in regard to human rights for English football. The Review concluded that an approach based on that used in financial services, including the ‘Joint Guidelines on the prudential assessment of acquisitions and increases of qualifying holdings in the financial sector’ should be adopted. This would involve an assessment by the IREF of whether the proposed owner or director is of good character such that they should be allowed to be the custodian of an important community asset. This approach will be (but not be limited to) the following:

a. The proposed owner will be considered of good character if there is no reliable evidence to consider otherwise and IREF has no reasonable grounds to doubt their good repute;

b. The IREF would consider all relevant information in relation to the character of the proposed owner, such as:

I. Criminal matters not sufficient to be disqualifying conditions.

II. Civil, administrative or professional sanctions against the proposed acquirer.

III. Any other relevant information from credible and reliable sources.

IV. The propriety of the proposed acquirer in past business dealings (including honesty in dealing with regulatory authorities, matters such as refusal of licences, reasons for dismissal from employment or fiduciary positions etc).

V. Frequent ‘minor’ matters which cumulatively suggest that the proposed owner is not of good repute.

VI. Consideration of the integrity and reputation of any close family member or business associate of the proposed owner.

Unanswered questions for the IREF

The question is whether these recommendations are sufficient to prevent ‘sportswashing’ like behaviour in the future. In the case of the Saudi/Newcastle United takeover, several questions would remain unanswered. Firstly, whether the character of a Chairman of a corporation having ownership is sufficient to ‘colour’ that whole corporation and disqualify them? Secondly, in the hypothetical that bin Salman had removed himself as Chair of the PIF, would the IREF be willing to pierce the legal assurances separating the PIF and Saudi State? Thirdly, would the IREF be able to act objectively and independently of foreign policy objectives where those owners in question are political figures or heads of state? Lastly, to what degree would the IREF hold sovereigns or heads of state liable for injustices committed by their country?

These are all questions the IREF will have to contend with at some point given the growing number of foreign sovereigns now involved in English football. Should the IREF fail to address these questions appropriately, and without sufficient and specific regard to human rights, even these very promising proposals could fall flat.

“Should the IREF fail to address these questions appropriately, and without sufficient and specific regard to human rights, even these very promising proposals could fall flat.”

Josh Sheehy and Max Chau, Newcastle Law School

Taking the proposals further: additional considerations

For this reason, the proposal for a renewed directors test should be considered in conjunction with other measures, and wording in the review is receptive to this.

Implementation of International Human Rights Framework

Primarily, this should include implementing a football-wide human rights policy. Neither the Premier League nor lower leagues have actionable human rights policies despite all giving considerable regard to values of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI).

It may simply be that English football has not yet been forced to contend with its proximity to broader human rights abuses, in the same way it has with race and gender. Having been drafted before the Saudi-Newcastle takeover, the fan-led review is also symptomatic of this undoubtedly important but seemingly narrow focus on EDI. Recommendation 23 of the review proposes the IREF enforces a mandate for clubs to draft and enact Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Action Plans yearly. These plans would set out the club’s objectives for EDI, and importantly, how the club is going to achieve them for the upcoming season. If the IREF deemed there to be insufficient progress made against the organisation’s plans, it would be able to enforce financial or regulatory sanctions.

Though these recommendations are sound, it would seem paradoxical for Newcastle United to, on one hand, be mandated to comply with EDI objectives amongst its staff and, on the other, to be permitted to receive finance from parties connected with human rights abuse simply because they have not been considered. EDI objectives are predicated on notions of equality enshrined amongst the broader set of humanist values and thus it seems both narrow-sighted and illogical to limit the IREF’s considerations to only few.

Consequently, to better address the full range of inequities the IREF might address, it should draft its own human rights policy or look to existing International Human Rights Frameworks already designed to be integrated into corporate governance flexibly. The best example is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Human Rights (UNGP) which set out business practices and responsibilities that would guide corporations towards conduct respectful of human rights. These principles would be enforced through the IREF licensing mechanism and could inform new elements of the proposed integrity test to better combat the broad range of wrongs the IREF could be forced to tackle.

Furthermore, it is worth considering that the issue of sportswashing is not confined to the Premier League. While a new regulator for English football may be able to tackle the problem in football, an entirely football-centric solution does not protect other sports or other public-facing sectors generally. On this basis, implementation and enforcement of the UNGP by the IREF could be an initial stepping stone in the adoption of these guidelines across all commercial and entertainment sectors more comprehensively.

Summary

Sports Minister Nigel Huddleston has said the government intends to “proceed at pace” in actioning the reforms but has only gone so far as to say it supports ‘the primary recommendation of the review, that football requires a strong independent regulator’. Fortunately, the leagues themselves have been more open about what they are looking to achieve through the IREF. Recently, the Premier League’s chief executive Richard Masters has indicated the league is receptive to broadening the proposed Owners and Directors Test to include human rights considerations, but further discussion must be had with the FA to before they can be coordinated across football.

While certainly promising, it will remain to be seen whether such changes will be sufficient to eliminate sportswashing. At the very least, should the government implement changes to the owners’ and directors’ test as they stand in the review, scrutiny over the character of those involved in English football will increase to the benefit of all. For the new owners of Newcastle United, compliance with this test will be evaluated on a tri-yearly basis, meaning scrutiny over their human rights record is by no means over. Hopefully, given continued concern voiced by the human rights community and enough vocal fans, the government will consider integrating human rights values into English football to a far greater extent going forward.

Until this happens, each of us should take note of the words of the great Alan Shearer, to ‘educate ourselves’ on the human rights record of incumbent and incoming owners. In doing so, football fans may be able to have their cake and eat it; benefiting from new money at their beloved clubs, whilst denying any attempts to erase their wrongdoings.

“Each of us should take note of the words of the great Alan Shearer, to ‘educate ourselves’ on the human rights record of incumbent and incoming owners. In doing so, football fans may be able to have their cake and eat it.”

Josh Sheehy and Max Chau, Newcastle Law School