In the Newcastle University public lecture on New Voices in Social Renewal, postgraduate student Stephanie Butler presented her work on letter-writing during the Second World War. In this blog post, she challenges the overly simplistic histories of English wartime stoicism, and explores the true resilience of English women as they adjusted to living through war. In deepening our understanding of war displacement, we can let our past inform our present, with an empathy fitting for the modern age.

Stephanie Butler, PGR, English Literature, Language and Linguistics

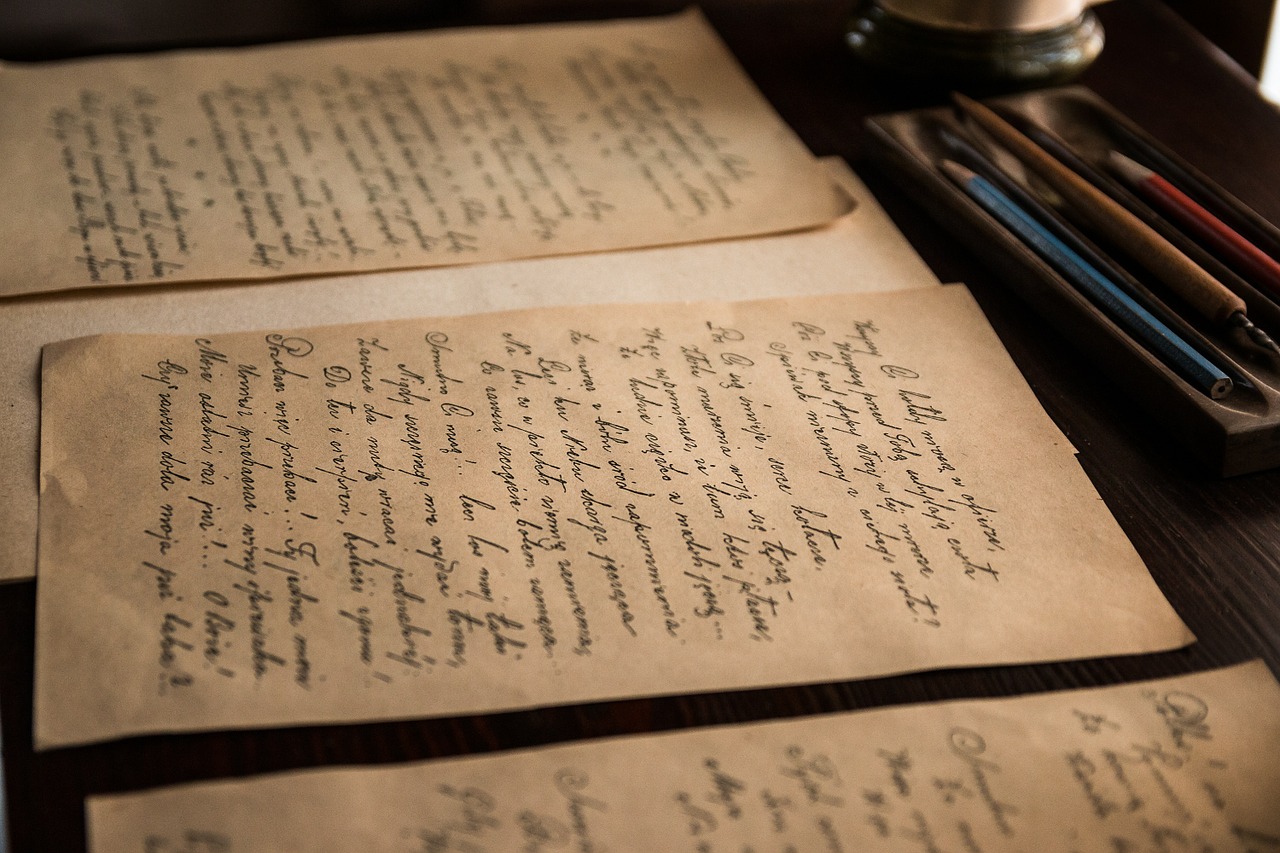

My doctoral thesis examines how English women used personal correspondence during WWII to create peer-support communities which promoted wartime psychological resilience. This project started as a result of letters I inherited from my grandmother, which were written by my grandmother’s great aunts to their sister (her grandmother). Each of the great aunts was in her late seventies by the end of the war, which means that they represent an age bracket often overlooked in research about WWII. They were certainly not war-working women [1], nor were they housewives [2] nor mothers of young children [3] – all of whom have been given a lot of scholarly [4] and popular [5] attention.

My grandmother’s great aunts’ letters are quite honestly heart-breaking at times. These letters are so full of references to shaken nerves, bombed houses, civilian war causalities, and even grief over massacred children, that the popular myths of English wartime stoicism [6] have long seemed overly simplistic to me. One of my grandmother’s great aunts lost her house in Kent after a bomb completely obliterated it and killed her neighbours. Another lost a friend and former teaching colleague who was killed (along with her three sisters) when a bomb fell on their house.

Their constant descriptions of houses, whether home repairs after bombing or concerns about potential air raid damage, led me to consider the ways war reshaped women’s relationships with their homes. Although the home is by no means a safe space for everyone, I wondered how the threat of violent death or displacement impacted women who had previously felt that their home was their own space of comfort and safety, or even accomplishment. Where could they feel safe if not even in their own homes? Private shelters such as Andersons [7] or Morrisons [8] or reinforced basements [9] were no guarantee of survival in the event of a direct hit (nor were public shelters [10]).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I noticed that women’s descriptions of the state of the houses around them (their own, or other peoples’) often reflected the overall emotional tones in their letters. At times women even connected—practically or symbolically—the physical stabilities of houses to their own mental states. This observation holds true across a wide collection of letters I have reviewed, not just those provided to me by my family. I, therefore, examine the ways that preoccupations with houses in their letters reveal the psychological impacts of war on civilian women.

Despite popular mythologized representations of English wartime stoicism [6], the realities of people’s reactions to the war were far more complicated [11]. What I have learned is that women’s negative reactions must not be dismissed as cowardly; they are an inevitable part of the process of adjustment to wartime conditions – an entirely human reaction. Letters were an important medium of support because women often found themselves separated from family and friends due to war-work, evacuation, or military service. (The telephone was expensive, and often interrupted due to raids or service cuts to international lines, so was not as popular [12]).

Letters then let women reach out to trusted confidantes when the war was too much for them to cope with alone. In the spirit of my usual concern with contemporary human rights issues, I contend that a more complicated understanding of English women’s responses to war displacement, evacuation, and endangerment can increase our empathy for those currently seeking asylum [13]. Inspired by American [14] and Canadian allies [15] who so generously supported English friends and relatives throughout the war, we can provide aid to contemporary women fleeing conflict [16].

References

[1] Braybon, Gail, and Penny Summerfield. Out of the Cage: Women’s Experiences in the Two World Wars. Abingdon: Routledge, 1987. Print.

[2] Last, Nella. Nella Last’s War: The Second World War Diaries of ‘Housewife, 49’. Eds, Richard Broad and Suzie Fleming. London: Falling Wall Press, 1981. Print.

[3] Clouting, Laura. ‘The Evacuated Children of the Second World War.’ Imperial War Museums. 2016. Web. December 21, 2015.

[4] Jolly, Margaretta. Dear Laughing Motorbyke: Letters from Women Welders of the Second World War. London: Scarlet Press, 1997. Print.

[5] Nicholson, Virginia. Millions Like Us: Women’s Lives During the Second World War. London: Penguin, 2012. Print.

[6] Calder, Angus. The Myth of the Blitz. London: Jonathan Cape, 1991. Print.

[7] Lewis, Tony. ‘What was an Anderson Shelter?’ Biggin-Hill History. http://www.bigginhill-history.co.uk/ May 14, 2015. Web. December 21, 2015.

[8] Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer ‘MORRISON SHELTER ON TRIAL: TESTING THE NEW INDOOR SHELTER, 1941.’ Imperial War Museums. 2016. Web. December 21, 2015.

[9] Your Home as an Air Raid Shelter. London: British Pathé, 1940. Film.

[10] Sunderland Libraries. ‘Fifty Years On: Remembering the Lodge Terrace Incident of 24th May 1943.’ BBC: WW2 People’s War. 18 January 2005. Web. January 24, 2016.

[11] Acton, Carol. Grief in Wartime: Private Pain, Public Discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

[12] ‘UK Telephone History.’ Bob’s Telephone File: A historical web site about United Kingdom Customer Telephone Apparatus & Systems. December 20, 2010. Web. December 21, 2015.

[13] ‘Free access to OUP resources on refugee law.’ Oxford Public International Law, Oxford University Press. 2016. Web. January 1, 2016.

[14] Statler, Jocelyn. Special Relations: Transatlantic Letters Three English Evacuees and their Families, 1940-45. London: Leo Cooper, 1990. Print.

[15] Hawes, Stanley. Children from Overseas. Montreal: National Film Board of Canada, 1940. Film.

[16] West End Refugee Service Website. January 5, 2016. Web. January 5, 2016.

Stephanie Butler is a Year three PhD Candidate in the School of English Literature, Language, and Linguistics at Newcastle University. Her publications on chronic illness peer-support and virtual autobiography have appeared in the journals Space and Culture; Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies; Disability Studies Quarterly; Information, Communication, and Society; and a/b:Auto/Biography Studies (forthcoming). She recently completed a Research Fellowship with the Saratoga Foundation for Women Worldwide, Incorporated (a United Nations Accredited NGO with Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the UN).