Professor Mark Shucksmith OBE, Newcastle University

Brexit will have significant effects on rural areas of the UK, but the challenges and opportunities these bring for rural economies and societies have been little discussed beyond farming impacts. Leaving the EU will require new thinking in relation to agricultural and environmental policy but also for rural businesses, communities and services. What national policies for each of the devolved territories should replace these after Brexit? Could this offer an opportunity to introduce better rural policies, suited to 21st Century rural potentials and challenges?

Rural policies in England, in particular, have been ripe for reform for many years[i]. Brexit could offer an unforeseen opportunity to rethink policy approaches. The Common Agricultural Policy will no longer apply, the Single Farm Payment and rural development funding such as LEADER will be swept away. Much is yet uncertain. Questions must be posed about what should replace the CAP, and much effort is being devoted to developing scenarios and alternative proposals for farm support and agri-environmental policy. But these questions should extend beyond agriculture, important though that is, because farming is now only a small part of the rural economy. And while most are no longer land-based, rural businesses make a substantial contribution to the national economy (19% of the country’s output comes from rural businesses). How then should rural businesses and rural communities be supported to give them the best chance of thriving and playing their full part in the future of the UK after we leave the EU? To help with this question let us consider two scenarios.

What could rural areas look like after Brexit?

2025 Scenario 1

Small businesses across rural England are struggling to survive as a result of what they describe as the ‘triple whammy’ of loss of markets due to export tariffs, skills shortages, and the closure of support schemes formerly funded by the EU’s regional policy and rural development policy. Farm families are hard hit, especially in upland areas such as our national parks and AONBs, by the loss of export markets and EU subsidies and by a reduction in opportunities to earn off-farm incomes. District, County and Unitary Councils lose funding as they are now reliant on Business Rates and Council Tax – services suffer. Environmental groups are concerned that land abandonment is damaging landscapes and habitats – tourism businesses suffer. Rural communities complain that the lengthy economic downturn and public spending cutbacks together with a failure to rural-proof national policies, are leading to losses of essential services, such as aspects of social care, health care, schools, leisure opportunities, shops and transport, with many voluntary and community organisations also having to close their services. Young people and older people requiring care face particular hardships. MPs representing rural constituencies are forming an all-party parliamentary group to promote the need for a coherent rural policy.

2025 Scenario 2

Small rural businesses are leading the economic recovery from the initial economic shock of leaving the EU. Aided by a national rural industrial strategy which recognises the economic potential of rural innovation and enterprise (including tourism and culture) and builds on lessons from the rural growth pilots, rural businesses are outperforming those in most cities. Farmers are adapting to the new trade deal with the EU and to new national support schemes which are better targeted toward provision of public goods such as landscape, wildlife, flood prevention and carbon sinks, and to diversifying income sources. Rural communities are thriving due to the growth in employment opportunities, renewed investment in affordable rural housing, and effective joint working between better-resourced and less financially challenged unitary, county, district and parish/town councils and community and voluntary organisations. These are all part of a new coherent rural strategy, agreed between central and local government and other key stakeholders, which is encouraging and enabling innovations in service and infrastructure provision, in planning and place-shaping, and in skills provision and business support. The OECD is sending a team of experts to study this successful approach so that other countries can learn from our experience.

What might be the elements of a successful, coherent rural strategy post-Brexit[ii]?

An asset-based, locally-led approach: In such an approach, place-based strategies are developed by local people collectively working with local councils as democratically elected, community leaders and deliverers of essential services but also involve external partners and networks. Primarily based on local assets and local knowledge, local groups also learn from one another through national and transnational networks, sharing ideas and know-how; and the necessary contribution of an enabling state in partnering, capacity-building and setting an enabling framework is also recognised[iii]. Without this, inequalities will grow between places – a recipe for a two-speed countryside.

A Rural Industrial Strategy: A crucial part of the enabling framework for rural entrepreneurial potential[iv] to be fulfilled, contributing to national productivity, growth and innovation, is an Industrial Strategy that encourages rural businesses and builds on learning from the rural growth networks. This does not just mean rural-proofing the recently proposed Industrial Strategy, vital though that is, but the adoption of an approach which has rural circumstances at its heart – a Rural Industrial Strategy. This would reflect the characteristics and contexts faced by rural businesses (typically microbusinesses, often home-based), addressing skills and training, business support, infrastructure, planning and finance – taking ideas both from the Rural Productivity Plan 2015 and from EU schemes such as the RDPE, LEADER and Objective 1 and 5b. Each LEP would be required to address rural issues through properly funded Rural Action Plans, informed by this Strategy.

A Rural Communities Strategy: Rural life opportunities and thriving communities are also core elements in such a vision. DEFRA Ministers have spoken of their determination to “keep our villages thriving and growing” and to ensure “people living in our market towns and villages have the same life opportunities as those who live in our cities” – something which is a statutory right in Norway[v] but is lacking in rural Britain[vi]. Rural citizens should expect a fair deal for rural communities – i.e. fair outcomes including access to services which meet needs; transparent decisions based on evidence; equal opportunities to participate in society; and a fair hearing and an effective voice in decision-making. The government’s allocation of resources to local authorities and other providers should reflect the additional costs of delivering services in rural areas and the extra time and cost for citizens of reaching distant, centralised services. This requires investment and innovation in the provision of affordable housing[vii], public spaces, connectivity, social care, health care and schools, among other essential services – often in partnership between public, private and VCSE sectors. There is much innovative practice to draw on[viii] but this is hampered by underfunding.

These two strategies could be underpinned by a Rural Social Innovation Fund, recapturing the creativity and capacity-building of early LEADER programmes, administered through local partnerships of councils and RCCs. The purpose would be to build capacity through animation, facilitation and knowledge exchange and to promote social innovation in service provision and social enterprise. Social innovation is increasingly recognised as a vital ingredient of dynamic economies and as a means of addressing the challenges of service provision in rural areas. In urban policy social innovation is well established in terms of a ‘quadruple helix’ of open cooperation and interaction between public authorities, private businesses, universities and citizens towards smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. International research[ix] suggests that rural regions may benefit even more from such models of open innovation. These would require a new social partnership operating transparently at multiple scales between public authorities, private businesses, universities and the citizens and voluntary and community organisations of rural areas.

Affordable rural housing: There is recognition at last of the urgency of addressing housing issues nationally, but in rural areas homes are even less affordable and there is much less social housing to rent[x], such that housing opportunities for even middle income households are very restricted. The Government’s affordable rural housing target should be reinstated with necessary budget and cross-subsidy provisions, alongside incentives to landowners to release exception sites, accompanied by powers for councils and housing associations to build small rural schemes exempt from the right to buy. The right to buy, mandatory or voluntary, should not apply in rural areas where unmet demand and need exceeds supply over the medium to long term.

Public goods and market failure: The British countryside contains iconic landscapes, precious habitats, flora and fauna, beloved cultural legacies – indeed a wealth of natural and cultural assets which depend on land management often without any market revenue. These public goods are highly valued by millions of people, as well as helping to support a low carbon future and green economy[xi]. Prince Charles, among others, has argued that the countryside is like a delicately woven tapestry, where land, farmers and communities are inextricably intertwined and may easily unravel. Their stewardship therefore requires targeted incentives and rewards for appropriate land management (within the constraints of WTO rules) alongside sustainable rural communities.

Coherent rural policy and implementation: Rural policy in each of the devolved nations necessarily reaches across the portfolios of many government departments, creating challenges of co-ordination, responsibility and accountability. None of the ten actions in the Treasury/DEFRA Rural Productivity Plan[xii] were DEFRA responsibilities, for example, although rural policy is scrutinised by the EFRA Select Committee which expressed its misgivings about the lack of co-ordination of rural policy in its report Rural Communities (2013). Since then the post of Rural Advocate and DEFRA’s Rural Community Policy Unit have been abolished, although a DEFRA Minister has the title of Rural Ambassador. Each of the devolved nations has developed their own approach to rural-proofing[xiii], but research suggests that a prerequisite for effective rural proofing is a coherent national rural policy which extends across all the departments of Government[xiv] .

The question remains of how best to ensure rural policy co-ordination:

- Across central government departments (leadership; rural-proofing[xv])

- Partnerships between local and central government (an England-wide ‘rural deal’?)

- At local level (subsidiarity and partnership with VCSEs)

Above all a New Coherent Rural Vision and Strategy is essential, agreed between all departments of central government, local government and other key stakeholders. This should enable realisation of the latent potential of rural economies and a fair deal for rural communities. It would include coherent leadership from within central government alongside an England-wide “rural deal” which shares power, resources and responsibility with local government and communities through a framework of devolution and capacity building.

[i] http://www.ippr.org/files/uploadedFiles/ipprnorth/events/rural_agenda_-_exec_summary.pdf

[ii] See also CRE (2017) After Brexit: 10 key questions for rural policy. http://www.ncl.ac.uk/media/wwwnclacuk/centreforruraleconomy/files/CRE_10_Key_Questions_final.pdf

[iii] Shucksmith (2012) Future Directions in Rural Development, Carnegie UK Trust.

[iv] Phillipson et al (2017) Small rural firms in English regions: analysis of UK longitudinal business survey, CRE

[v] Shortall S and Alston M (2016) To Rural Proof or Not to Rural Proof? A Comparative Analysis, Politics and Policy, 44, 1, 35-55

[vi] Social Mobility in Great Britain, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/662744/State_of_the_Nation_2017_-_Social_Mobility_in_Great_Britain.pdf

[vii] Rural Housing Policy Review, 2015.

[viii] CRE (2015) Reimagining the rural: What’s missing in rural policy? CRE

[ix] Kolehmainen et el (2015); Nordberg 2013)

[x] ACRE Rural Housing Position Paper, 2017 http://www.acre.org.uk/cms/resources/policy-papers/housing-position-paper-final-a4-pages.pdf

[xi] Commission for Rural Communities (2010) High Ground, High Potential, CRC.

[xii] HM Treasury/DEFRA Rural Productivity Plan, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/454866/10-point-plan-rural-productivity-pb14335.pdf

[xiii] Shortall (2017) Rural-proofing: magic bullet or rural vote catcher? Newcastle University Institute for Social Renewal https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/nisr/rural-proofing-magic-bullet-or-rural-vote-catcher/

[xiv] Shortall S and Alston M (2016) To Rural Proof or Not to Rural Proof? A Comparative Analysis, Politics and Policy, 44, 1, 35-55

[xv] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rural-proofing

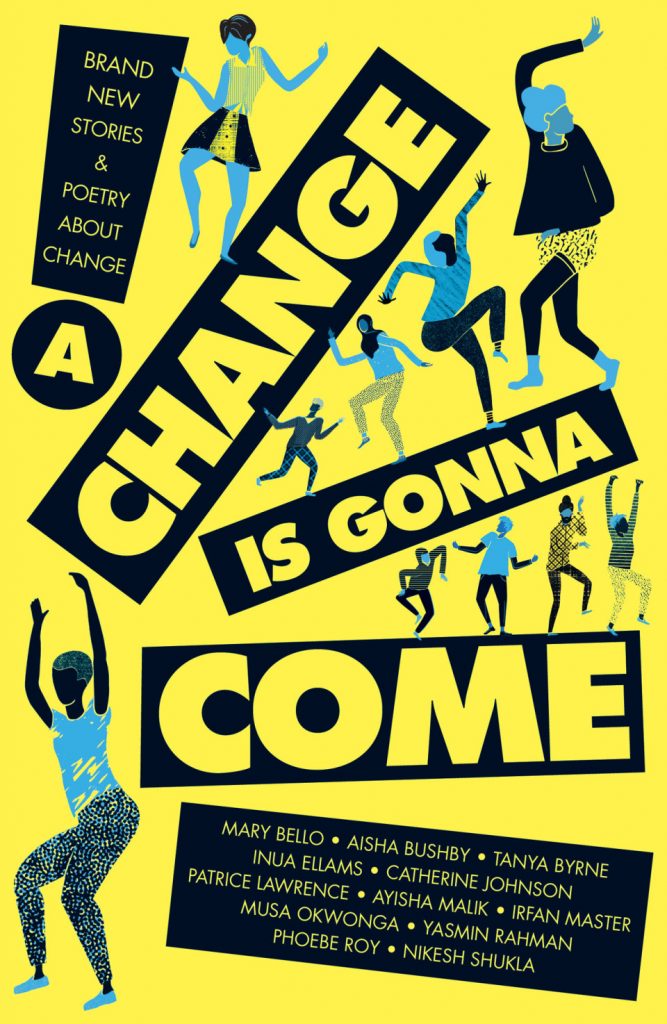

The brilliant and optimistic collection from Stripes includes writing from Diverse Voices? participants Darren Chetty, Patrice Lawrence and Catherine Johnson.

The brilliant and optimistic collection from Stripes includes writing from Diverse Voices? participants Darren Chetty, Patrice Lawrence and Catherine Johnson.