Archiver’s Note:

This exchange was discovered in the archives of Dormition Cathedral, London, in 2019 and believed to have been performed during several sermons in the late 1590s. The author is unknown; however, it is likely that this exchange was written by the church heads in order to educate the population on the immoralities of the theatre and to dissuade them from attending. Despite this, they were not able to prevent dwindling church attendance and the dialogue was never performed again.

Fool. What a glorious time to act upon the stage! Theatre doth grow in in popularity more and more each day. The rising men of about town are attending and it is attracting the attention of many a aristocrat. (Pollard, xii) The theatre has the power to change individuals just with words, that is some power that those actors hold and should not be ridiculed by the likes of you. The theatre has the power to enlighten and open minds as well as to teach. “What coward to see his countryman valiant would not be ashamed of his own cowardice?” (Heywood, 221). The plays can teach the proper manners expected of our nobles and our countrymen, set examples for thine own followers.

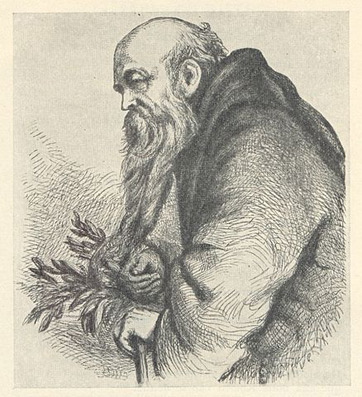

Friar. Fool! How far thee have strayed from the arms of our Lord and saviour. Your blasphemous disregard towards our teachings, replaced with vile sins and vanities, has brought about thy own damnation! Tragedies encourage wrath, cruelty, incest, injury, murder either violent by sword, or voluntary by poison; the persons gods, goddesses, furies, fiends, kings, queens and mighty men!” “the ground work of comedies is love, cozenage, flattery, bawdy, sly conveyance of whoredom; the persons, cooks, queans, knaves, bawds, parasites, courtesans, lecherous old men, amourous young men.” (Gosson, 94). Thou must return to thy holy Father!

Fool. How can thou call it a sin when your own Lord hath never done, “Neither Christ himself, nor any of his sanctified Apostles, in any of their sermons, acts, or documents, so much as named them, or upon any abusive occasion touched them.” (Heywood, 223).

T’was your very own clergyman who hath engaged in this art. Many preachers have in fact written for the stage and have provided us with many moral lessons within them (Pollard, xvii). How can the likes of ye argue against the immorality of plays when you yourself hath written and acted for the masses. Even your Sunday sermons could be seen as a performance with the intent on teaching. Ye argue that we encourage the wrath and sins of mortals and that we perform “the work of the devil” (Gosson, 84), why not then create your own work of God to counteract our deceitful act? “Since God hath provided us of these pastimes, why may we not use them to his glory?” (Heywood, 224)

Friar. Plays may be used by the Lord to teach and to guide in the right hands, but these theaters are filled with the devil’s very own lies and slander! “The proof is evident, the consequent is necessary, that in stage plays for a boy to put on the attire, the gesture, the passions of a woman; for a mean person to take upon him the title of a prince, with counterfeit port and train; is by outward signs to show themselves otherwise than they are” (Gosson, 102). There are no morals to be found in the bawdiness of theatre! “Hail the horse whose mischief hath been discovered by the prophets of the Lord…damnable, because we profess Christ, and set up the doctrine of the devil.” (Gosson, 89)

Fool. The theatre hath been used to perform the very truthful acts of mortals. “Plays hath taught the unlearned the knowledge of many famous histories” (Heywood, 241). The histories of our country hath been depicted on these very floors to inform and teach these good countrymen of their own past. The past itself hath believed our art to be one of taste. “Thus our antiquity we have brought from the Grecians in the time of Hercules; from the Macedonians in the age of Alexander; from the reigns of Romans long before Julius Caesar” (Heywood 246-247)

Friar. Thou thinkst that in the hands of fools knowledge will be used for the betterment of all? Dost thou proclaim that thou knowst better than thy Lord? “The devil, not contented with the number he hath corrupted with reading Italian bawdry, because all cannot read, presenteth us comedies cut by the same pattern” (Gosson 90). What use is history, will it teach our youth to fear our God? Let the history rest in the past, the only thought tat is needed in the hands of peasants and fools is the fear of God!

Fool. Hark! The gates of hell have opened! And yet, I cannot repent this addiction to the sin the theatre! I shall spend the rest of my days in the arms of sloth and lust. But, hark a second time! There is water arising from every corner of the world! God has brought upon us a second flood! Jesus, save us!

Friar. For shame! I pray for thee and thy sinful nature! God have mercy on thy soul, that you thee repent your Devil father. And I pray for this sheer crowd of a thousand sinners that flock to your feet, that they too repent and revoke this devil’s work!

Fin.

Omer, Ciara, Alfie D, Alfie P, Alice, Emma

Bibliography:

Pollard, Tanya, ‘Introduction’ in Shakespeare’s theater: A sourcebook. (2003). Oxford: Blackwell.

Gosson, Stephen, ‘Plays confuted in five acts’ (1582) in Shakespeare’s theater: A sourcebook. (2003). Oxford: Blackwell.

Thomas Heywood, ‘An Apology for Actors’ (1612) in Shakespeare’s theater: A sourcebook. (2003). Oxford: Blackwell.