At a time when newspapers were taxed, broadsides were vehicles for popular culture which were just affordable by the working class (the average cost of a broadside was a penny, with some ballads costing a ha’penny.) Typically, broadsides were single sheets, printed on one side only. Some communicated public information; many were printed for entertainment. They were ephemeral – cheaply printed for distribution among the lower and middle classes by chapmen, hawkers and street criers, or, for pasting onto walls by way of reaching wider audiences. In the Nineteenth Century, machine-press printing helped to bring about a proliferation of this street literature. It is remarkable that any broadsides have survived and yet almost 850 have been catalogued and digitised from Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections.

One of the many themes to be treated in broadsides, is crime. The end of the Eighteenth Century/beginning of the Nineteenth Century saw increases in both crime and poverty, with the majority of criminal acts being property offences. More goals were being built but there was also a move away from harsh punishment, with transportation replacing execution for some serious crimes and more lenient sentences, with attempts at rehabilitation, replacing harsh sentences for petty crimes. The first police force was introduced in 1829 and there would not be an organised police force until 1856 and so it was that prosecutions were usually brought about by private individuals; usually the victims of the crimes. Prosecution associations were community organizations whose members were citizens that paid dues to cover the costs of private prosecutions. Sometimes, they provided a form of crime insurance. Broadsides 5/1/35 5 Guineas Reward is evidence that these prosecuting associations also covered the costs around soliciting information: printing reward notices and contributing reward money.

Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections has several reward posters that were printed under the auspices of the North Shields and Tynemouth Association for Prosecuting Felons. Like the hanging ballads, these reward posters were formulaic, made use of stock woodcuts and were cheaply printed. They were moralistic, casting criminals as “evil disposed” persons that carried out their deeds “maliciously” even though the crime might have been the theft of food to feed the family.

In this example from 1818, Monkseaton farmer John Crawford has suffered criminal damage to a gate, two ploughs and a railing. He has put up three guineas (roughly £180.90 today) as a reward for information leading to successful prosecution and the prosecution association has increased the reward by two guineas (roughly £120.60 today).

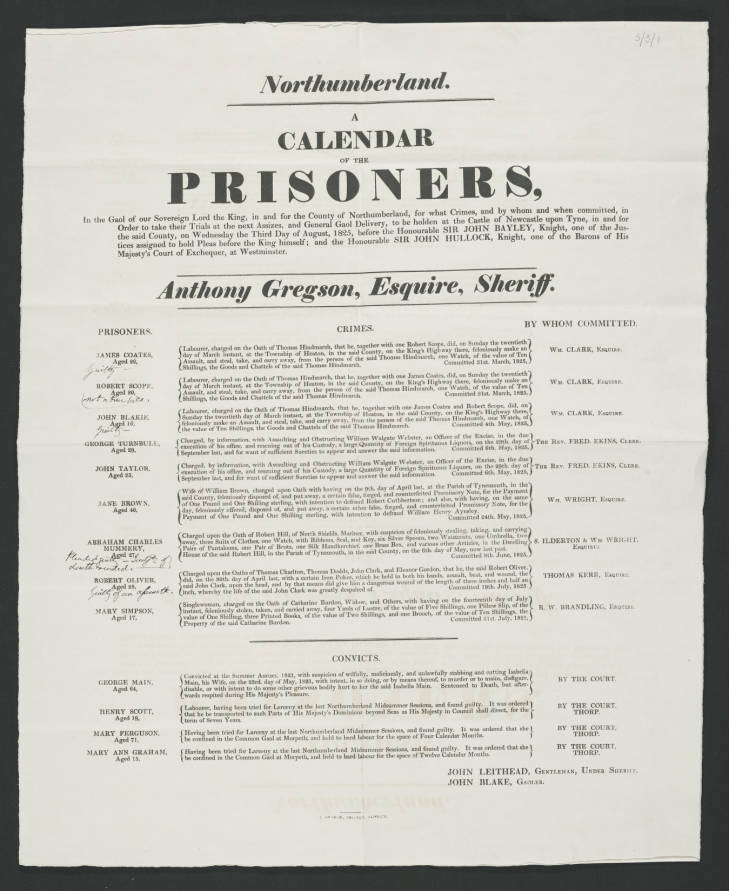

Calendars of Prisoners, like Broadsides 5/3/1, are lists of prisoners awaiting trail. They are formal documents, typically providing the names, ages, trades and offences of the accused as well as the names of the Magistrates that committed them.

This example lists the prisoners awaiting trial in Newcastle, in August 1825. The prisoners range from Mary Simpson (age 17) who was accused of stealing fabric, pillow cases, books and brooches to Robert Scope (age 80) accused of assault and theft. Some of the printed entries have been annotated by hand to record the verdict after trial. There is also a section for convicts at the end of the document: those prisoners to have been found guilty at trial and which have now been sentenced. They include Mary Ferguson (age 71) who was sentenced to gaol and given four months’ hard labour, such as working the treadmill.

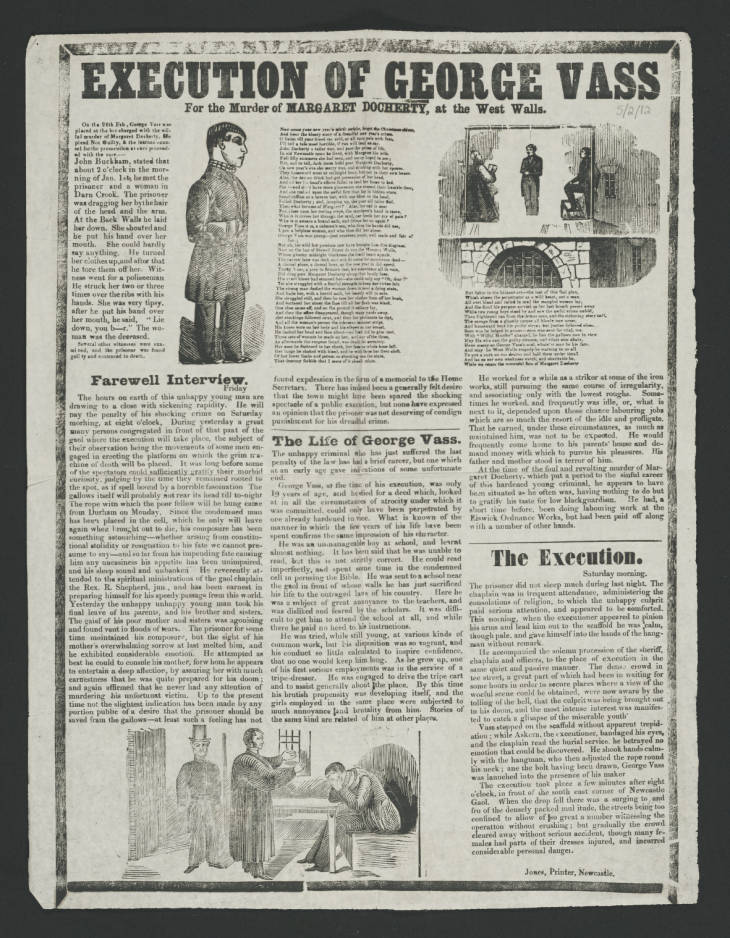

Broadsides 5/2/12 Execution of George Vass, is an example of a hanging ballad, or execution ballad. In the Nineteenth Century, public executions attracted large crowds of spectators and one of the ways in which people experienced public executions was through broadsides and ballads. Hanging ballads would be sung at executions and the ballad sheets sold by the singers. They were formulaic but combined news from local reports with sensational, moralistic accounts of the crimes committed. The audience could expect to learn about the crime, the behaviour of the prisoner, an account of his/her last words, a description of the execution and a warning against leading a similarly criminal life lest the audience end their days at the gallows too.

George Vass was 19 years old when he became the last person to be executed by public hanging in the Carliol Square gaol, Newcastle upon Tyne, at 08:00 on 14th March 1863. He had been found guilty of the rape and murder of Margaret Docherty on New Year’s Eve 1862. Margaret lies in the cemetery of All Saints Church.

In the Nineteenth Century, crime was never far from the common people and, through broadsides and other publications, knowledge of criminals and their crimes became well-known; often sensationalized.