The story of Dr Ruth Nicholson and the women of Royaumont Military Hospital

This is an online version of the exhibition People don’t know about them…, which was on display in the Marjorie Robinson Library Rooms, Newcastle University, 28th October 2016 – 15th January 2017. The exhibition was the result of a collaborative oral history project based at Newcastle University Library, and part of the Universities at War programme.

Many thanks to the creators of the original exhibition, Sam Wagner and Rosemary Nicholson.

Three Women

Our story starts with Rosemary Nicholson, a local Newcastle woman who contacted the Universities at War project to tell us about her husband’s aunt Ruth – a Newcastle University medical graduate who had worked as a surgeon in a military hospital in France throughout the First World War, under the direction of the French Red Cross.

A female medical graduate?

A military hospital staffed entirely by women?

And why the French Red Cross?

The story caught the eye of Sam Wagner, an archaeology student in her final year of study at Newcastle University, who had joined the Universities at War project in 2015.

Sam’s exhibition is the result of her own historical research and interviews with Rosemary – capturing her memories of family stories about Ruth, as told through Ruth’s sister, Alison, who was still alive when Rosemary married into the family.

It is the fascinating story of an amazing Newcastle woman, whose story had been almost forgotten – passed on by the women in her family who had never forgotten and who wanted her story to be told.

The College of Medicine – Newcastle upon Tyne

Ruth Nicholson completed her high school education at Newcastle upon Tyne High School and registered as a student at the College of Medicine in 1904. After graduating in 1911 she worked in a dispensary in Newcastle before going to Edinburgh where she became an assistant to Dr Elsie Inglis in the Bruntsfield Hospital. As Rosemary states, she then worked in Palestine before returning to England at the outbreak of the First World War.

“There were seven of them all together, one brother and Ruth the eldest. This was taken at Newton Vicarage where they lived later on in their father’s life. Their father was a vicar.

Their mother was rather a remarkable woman I think for her time because she wanted all her children to get professional qualifications regardless of whether they were men or women … So Ruth qualified as a doctor in Newcastle, and then the youngest, Wyn, also qualified as a doctor. The only one who didn’t get special qualifications is Alison. She was always rather a joke in the family. She had a lover in Romania and that’s what distracted her!”

“That picture’s Ruth in 1909 when she qualified … she qualified as the only woman in her year. And I think that she probably was quite a convinced suffragette. I don’t know whether she was a suffragette or a suffragist but you know Newcastle was a centre for a quite militant suffragette movement … Newcastle had some quite militant women!

It was quite difficult I think for women to get work as doctors in England. She went to work briefly in Edinburgh with a very distinguished woman doctor called Elsie Ingles and then she went to work out in Palestine in Gaza, which was before the First World War.”

The start of the First World War

“And then 1914, obviously the First World War is declared and she came back to England, and she’d been working as a surgeon. She offered her services to the War Office and the War Office accepted her and said yes and then she got her kit together and turned up at Victoria Station in London to join her group to go out to France to the military hospital out in France and the doctor in charge said “I’m not having a woman. I’m not taking her”.

So she was very, well according to the family, she was terribly terribly angry and upset. And she went back to Elsie Inglis in Edinburgh … she’d [Inglis] started a 100-bed hospital entirely with women, it was called the Scottish Women’s Hospital and she had also offered her 100-bed hospital to the War Office but the War Office said – I’ve forgotten what it is exactly they said – something like “Go home and sit down”.

She didn’t like that!”

Rosemary’s family stories appear to be entirely correct. Research by the National Archives confirms that Inglis was told by an official “My good lady, go home and sit still”. In her 1928 book, The Cause, Ray Strachey found evidence of accounts that suggested the commanding officers had told Inglis they “did not want to be troubled with hysterical women”.

The Hospital at Royaumont

“ So they offered the hospital to the French in London – the French Ambassador and he said “yes please” the French would like them, because apparently the French, this is again just through the family myth probably, the French were very aware of the deficiencies in their medical services and they were worried when the war was declared.

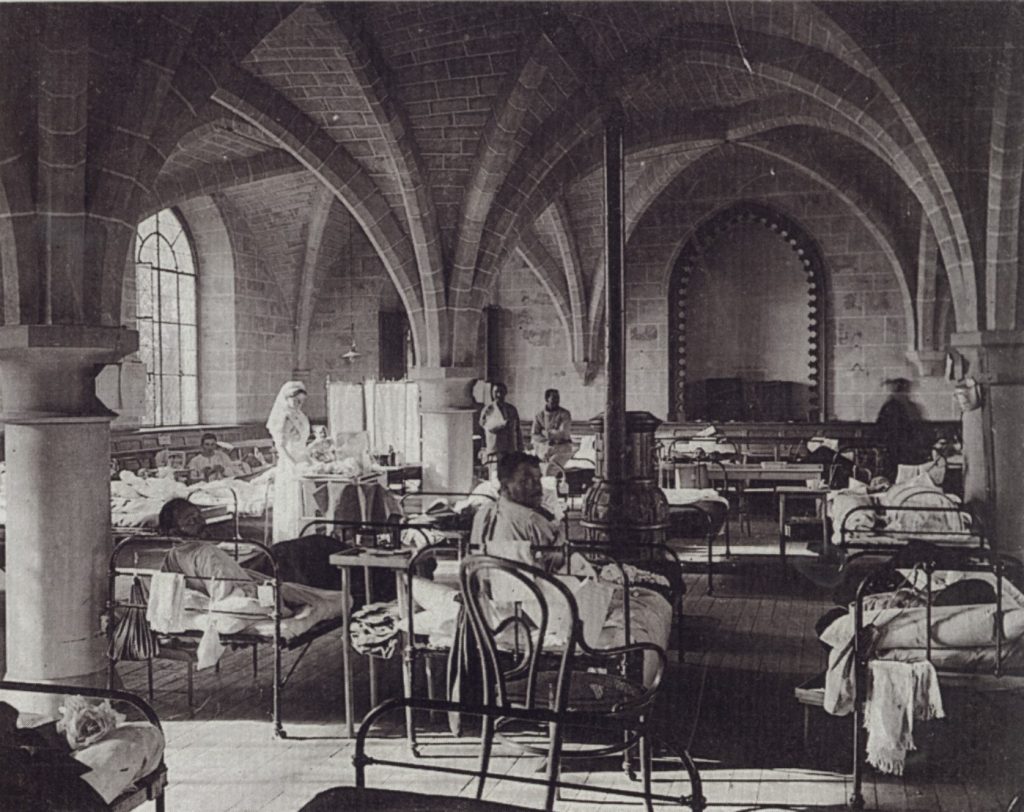

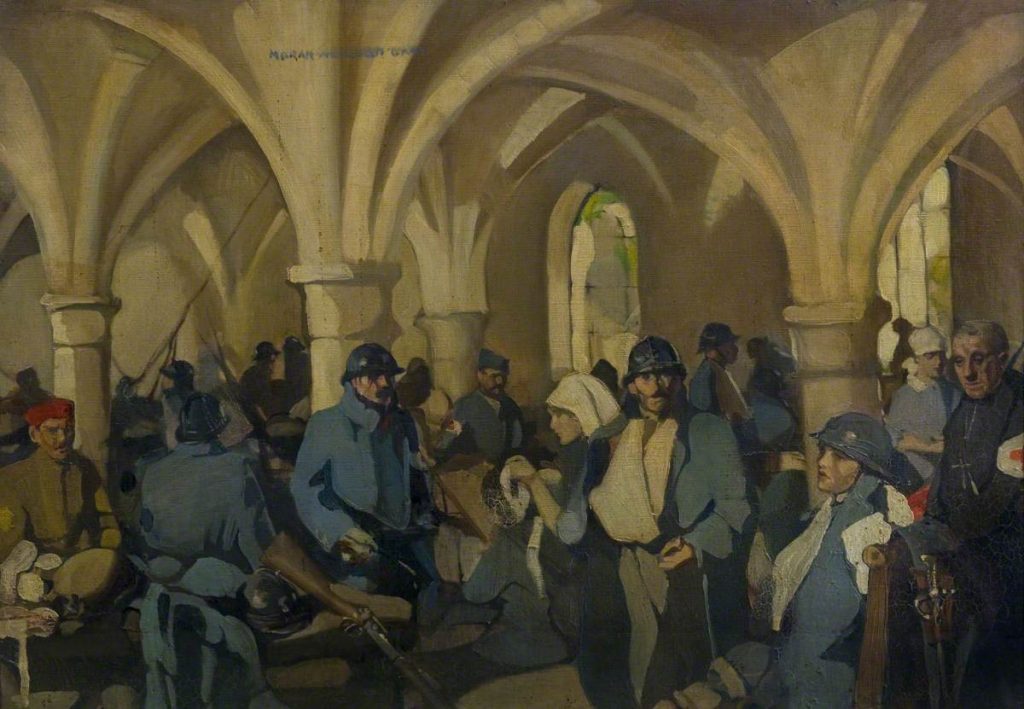

The president of the [French] Red Cross found them Royaumont, but Royaumont, the abbey hadn’t been inhabited for quite a long time; been used as stables and it had no, I don’t think it had electricity and it didn’t have any lifts, which they found really really difficult for dealing with stretchers and trolleys and things like that when they opened the abbey. The abbey was full of nuns, they were kind of helping out, but it was an empty shell of a building and it was in a terrible state. So, quite how they managed to get it open by 1915, I don’t know what they did.”

Royaumont was the largest continuously-operating voluntary hospital in France at the end of the First World War – over 10,000 patients were treated at Royaumont and its mortality rates were better than its army-run equivalents.

“ They started with 100 beds and by the end or at some stage, they had 600 beds. You probably know that, and some of the wards had 100 beds in them… I mean, I just don’t know how they coped, I don’t know how they did it…They were tough, I think, really tough.”

“ Unfortunately, I never met Ruth because she lived in Devon and she died in 1963, and my husband and I got married in 1962 and I never met her… but I knew Alison because she lived locally [Ruth’s sister Alison had also served in the Royaumont hospital, as an orderly, from September 1916 – March 1919]. I knew her quite well. And she used to talk about it all – they went on having Royaumont reunions right on until the sixties, the middle sixties, you know, which is a long time, you know… She talked about how traumatised people were, nightmares, they continued to have nightmares about it and things. And the doctors too, I think. I think it must have been awful. Really awful.”

“ I make it sound all gloom … but obviously in the First World War they had times of terrible crisis and awful fighting and then other lulls and really not much happening. And apparently, the nursing staff and the doctors, I supposed they were very used at home to providing their own entertainment and things and they would put on shows … Well Ruth, apparently had learnt how to do, while she’d been in Palestine, Dervish Dances, I think she called them her scarf dances! I think the patients liked them a lot!”

The Scottish Women’s Hospitals depended on an extensive network of fundraising, much coming from the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) whose London units provided an x-ray van. Newnham and Girton colleges in Cambridge provided both money and volunteers, as did women in the USA and around the world.

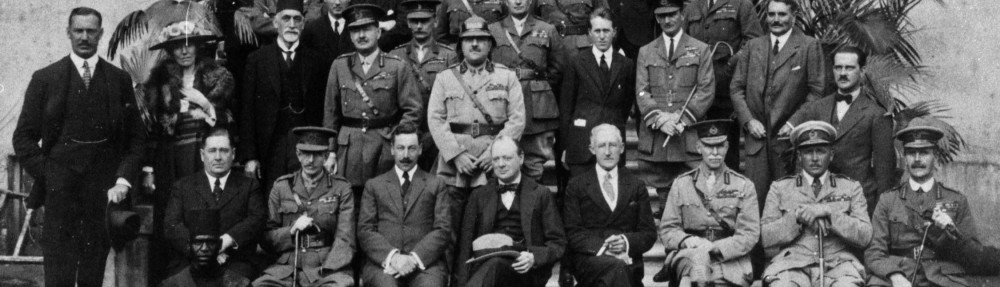

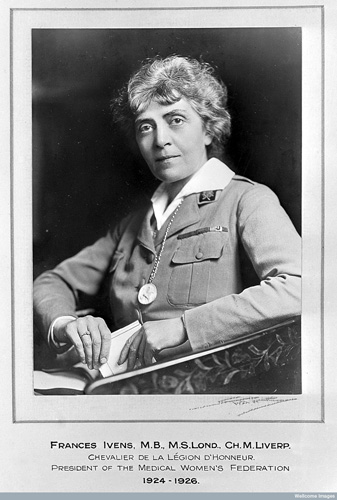

Frances Ivens was the first foreign-born woman to be awarded the Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest honour, and thirty of her Royaumont colleagues were awarded the Croix de Guerre.

“ And then at the end of the war, these are some of the doctors who got French medals. They got the French Criox de Guerre. This is Frances Ivens … she was the first non-French person ever to get the Legion d’Honneur.”

“ There were two surgeons, Ruth of course, second in command of the hospital I think they called her, and the boss was called Frances Ivens. She was … the rather inspirational woman in charge … I think it’s incredible that quite a lot of the women who came out to be ambulance drivers actually brought their own cars, and had them slightly transformed I think! So, quite a lot of quite rich, I think, young women who could provide their own vehicles. ”

After the War

After the war Ruth specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology and became Gynaecological Surgeon and Clinical Lecturer at the University of Liverpool and was one of the earliest Fellows of the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. She became the first woman President of the North of England Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and played a prominent part in the Medical Women’s Federation. Dr Ruth Nicholson died in Exeter on 18 July 1963.

“ I felt she never got the credit she should have had, or the recognition she should have had, or Alison.

People don’t know about them, I mean I write to everybody. I heard the programme on Women’s Hour about the women’s hospital in London and I rang right in to them saying, you know, “What about Royaumont?!”

It was a matter of pride!”