Written by Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives bequest student, Sam Bailey.

Books have a limited lifespan. The idea that one might deliberately take apart a book and use it for something other than the transmission of the written word might be cringe-inducing, but it was a practice that was widespread in the medieval and early-modern periods. When a book was no longer of use – because it was undesirable, out of date, or had been used to destruction, the expensive materials used could be recycled. John Dryden wrote in Mac Flecknoe (1678-83) that even the works of modern authors were destined to be ‘Martyrs of pies, and reliques of the bum.’ Anna Reynolds has recently shown how early-modern England was brimming with reused and repurposed scraps of paper, which provided imaginative inspiration for a variety of literary works. To our knowledge, the Philip Robinson Library does not contain any books that were once used in pie crusts or as lavatory paper, but it does contain books that were repurposed as binding material. Two books held in Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives, from the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries respectively, offer a window into the way that people recycled old books into new ones.

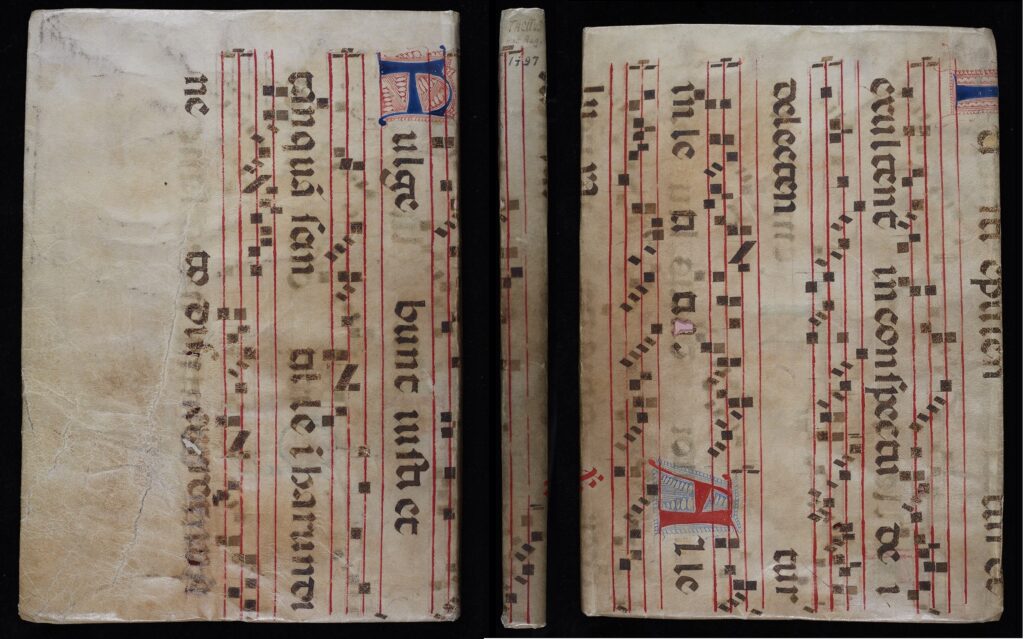

Incunabula 11 is an edition of the complete works of Tacitus, printed in Venice in 1497. Unfortunately for Tacitus, most of the attention that this copy receives is due to its remarkable binding. As you can see from the images below, this book is bound with a limp membrane cover, which was once a beautiful piece of sheet music. The music that is visible here is from a chant: De Sancti Martyribus, which was sung to commemorate Christian martyrs. This is a well-presented manuscript, in a regular hand with decorated capitals. Why is this high-quality music manuscript on the binding of a printed book? The historian of medieval music Margaret Bent can help to answer this; she argues that in the medieval period:

Musical styles changed almost as rapidly as in pop music today, and even new pieces were often adapted, with added or removed voices or changed text. Old music books were regarded as expendable, sometimes dismembered within half a century; parchment was recycled for miscellaneous purposes, paper usually discarded. (623)

Margaret Bent

This chant most likely fell out of fashion and ended up as waste material. It is likely, based on the observable structure of the book, and the dating of both the text and the binding, that this manuscript was used to bind the book shortly after it was printed. From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, most printed books were sold as ‘quires’ – unbound stacks of printed sheets that needed to be folded, trimmed, and then covered by a bookbinder. Bindings could therefore be customised based on the budget and tastes of the buyer. Music manuscripts were widely used as binding materials, a well-made manuscript made for a visually appealing cover. As membrane or leather were expensive animal products, reusing material in this way could cut costs for the purchaser. We do not know who first purchased this book, but if they were in an institution such as a monastery, it is possible that they already owned this discarded music manuscript, and reused what was available to them.

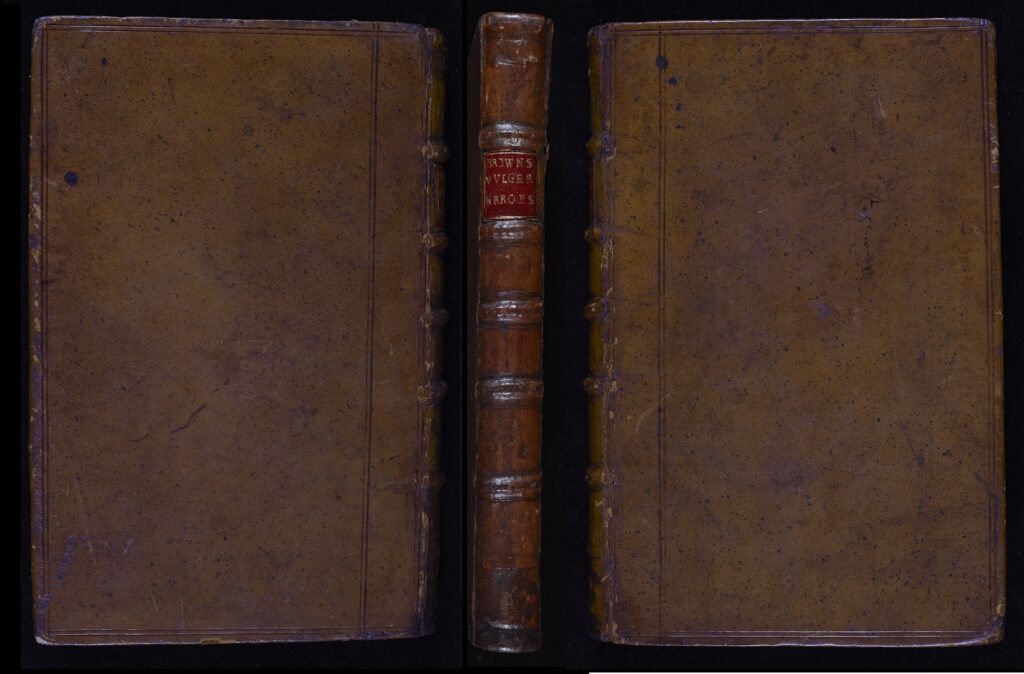

Our second book rockets us forward two hundred years, to the midst of the English Civil War and Interregnum of the 1640s. This is a copy of Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia epidemica, also known as Vulgar Errors, a work of natural philosophy. It was printed in London in 1646, and it is bound in a typical mottled brown leather binding, with decorative blind rules on the top and bottom covers. Binding styles can be somewhat misleading when dating a book, particular as a style as generic as this endured for so long. Understanding precisely when a book was bound can offer a vital insight into provenance, and luckily, the wastepaper used in this book’s binding gives us a vital insight into its history.

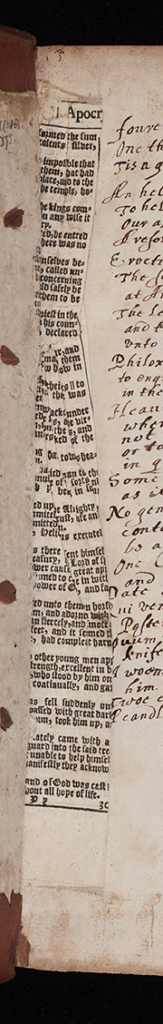

Peeking out between the top cover and first leaf of the printed book, we can see the edge of a single leaf of another book. This is a leaf used as a binding scrap – a piece of paper used to maintain the structure of the binding, that is a feature of many hard-cover bindings. Binding scraps were made from wastepaper that was available to the bookbinder at the time. If we can date the binding scrap, then we can identify more precisely when the book was bound. At the top of this scrap, we can see part of the word ‘Apocrypha’, and we can see in a small blackletter typeface, a number of lines from scripture. A quick comparison between some of these lines and quotations from the Apocrypha sections of English Bibles reveals that this leaf contains lines 26-32 of the 2nd verse from the 2nd book of Maccabees, and lines 1-29 from the 3rd verse of the same book. From that, it is possible to compare printed editions of English Bibles that contain Maccabees and find out which edition this leaf originated from. At the bottom of the page, we see a ‘signature’ – an alphanumeric representation of the position of the leaf within its sheet, that would help bookbinders to keep the sheets in the correct order. In this case, the signature is ‘Yy’ which we can express as 2Y1 (i.e. the first signature of the second sheet labelled Y). To find the edition of the Bible from which this binding scrap was taken, all we must do is find Bibles where these verses are found on leaf 2Y1 and compare them. Only one edition of the appropriate period has these verses, in the same typeface, on sheet 2Y1: the 1641 Authorized King James Bible printed by Robert Barker and John Bill in London. If you compare our scrap to a full leaf from this edition they match perfectly.

1646 – the year that this edition of Vulgar Errors was printed – was a tumultuous year in England. The parliamentarians had won the civil war against Charles I. The new Puritan-controlled Church issued a new Catechism, a Confession of Faith and a Directory of Worship – documents that sought to transform the nature of the established Church of England. That Confession would reject the authority of the Biblical Apocrypha. Our scrap of Maccabees 2 – from a 1641 Bible, was an example of this newly rejected scripture. New Bibles would be issued without the apocrypha and some old Bibles had their apocrypha sections removed. This is most likely how these verses from Maccabees 2, taken from a fairly new 1641 Bible, ended up as scrap paper in the binding of a 1646 book. The removal of this leaf was intended as an act of textual destruction, but it lives on by serendipity in the spine of another book. This scrap of paper, tucked into the binding of an otherwise unrelated book, is a register of the ways in which political and religious turmoil shaped the lives of books.

Acknowledgement

I must give all credit to any meaningful identification of the sheet of De Sancti Martyribus to my colleagues in the department of music at Newcastle University: Michael Winter and James Tomlinson. What took them minutes would have taken me days!

References and Further Reading

17th C. Coll. 398.3 BRO. Browne, Thomas. Pseudoxica epidemica. London: 1646. Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.

Authorized English Bible. London: 1641.

Bent, Margaret. ‘Polyphonic Sources’ in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music. Cambridge: 2011.

Dryden, John. Mac Flecknoe, Or, A Satyr upon the True-Blew-Protestant Poet, T. S. by the Author of Absalom & Achitophel. London: 1682.

Inc.11. Tacitus, Cornelius. Opera. Venetis: 1497. Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.

Korpman, Matthew J. ‘The Protestant Reception of the Apocrypha’ in The Oxford Handbook of the Apocrypha, ed. Oxford: 2021.

Marianai, Angela., Giger, Andreas and Thomas J. Mathiesen (eds.). ‘Regino Prumiensis’ in Theseaurus Musicarum Latinarum. REGTONA_TEXT (indiana.edu). (Contains the text of Di Sancti Martyribus)

Morrill, John. ‘The Puritan Revolution’ in The Cambridge Companion to Puritanism, ed. John Coffey and Paul C.H. Lim. Cambridge: 2008.

Reynolds, Anna. Waste Paper in Early Modern England: Privy Tokens. Oxford: 2024.