Newcastle seems to be experiencing an endless period of building and regeneration. The Evening Chronicle recently reported that a ‘run-down corner of Newcastle city centre is currently being redeveloped to bring new office buildings, a public square, shops, bars, and restaurants. ‘Pilgrim Place’ is currently being built in an area on the eastern side of Pilgrim Street, after the scheme was approved by Newcastle City Council’s planning Committee in July 2021.

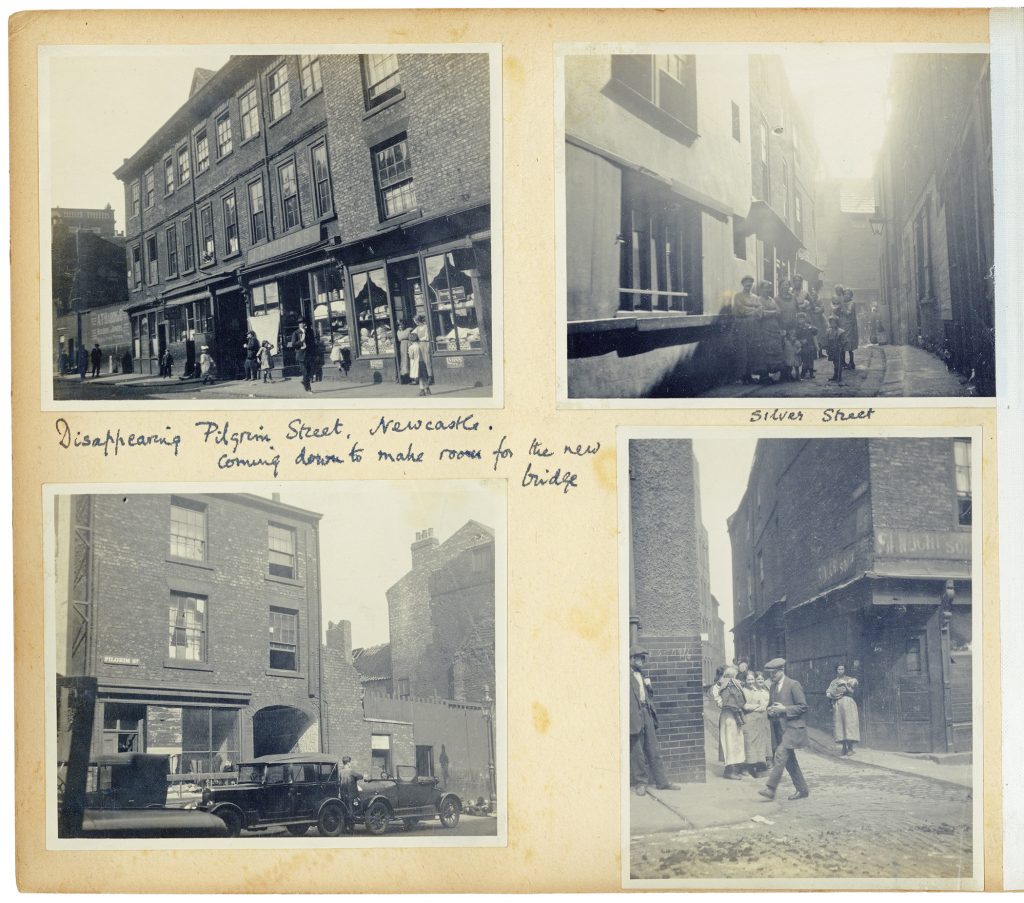

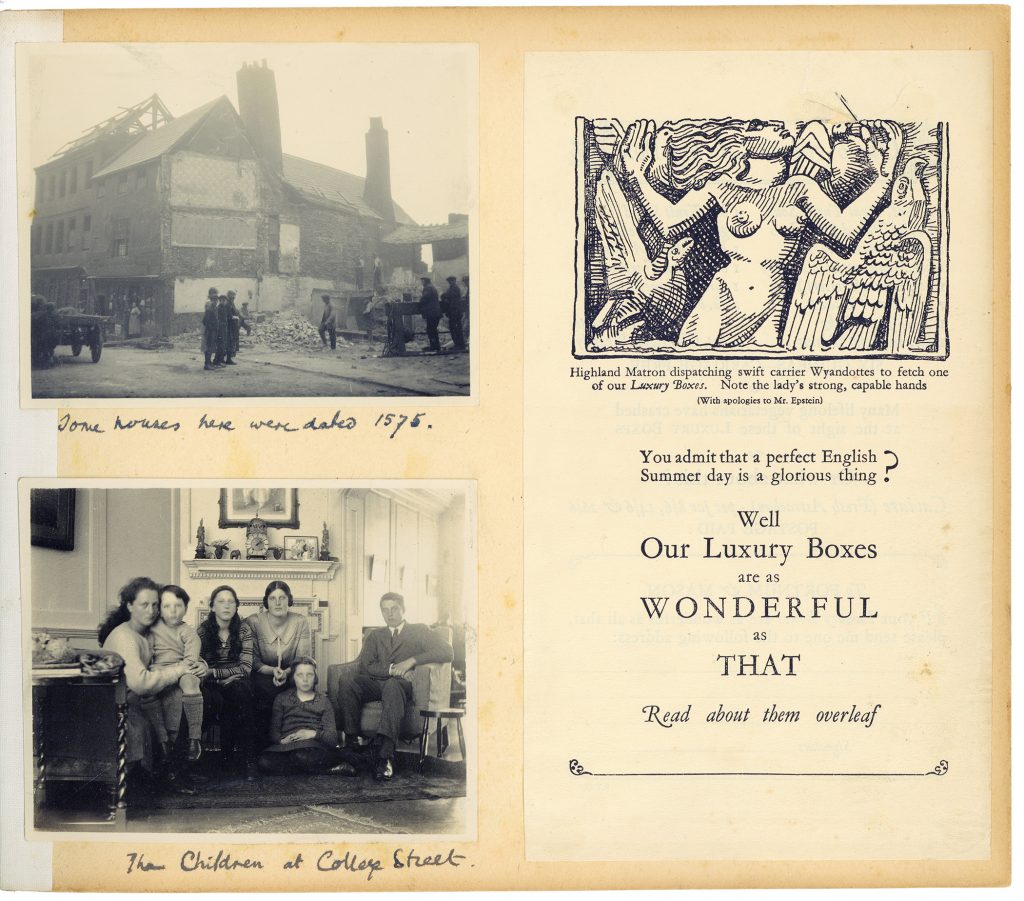

As a main route into (and out of) Newcastle, Pilgrim Street has been the centre of many similar schemes in the past. When construction of the Tyne Bridge commenced in 1925, the lower end of Pilgrim Street was cleared of many historic buildings dating back to the Sixteenth Century.

When the Swan House roundabout was built between 1963 and 1969, more buildings were demolished, including the ‘revered’ Royal Arcade which many people still mourn, even though it was never a commercial success and had fallen into disrepair due to its location outside the main shopping area of the city.

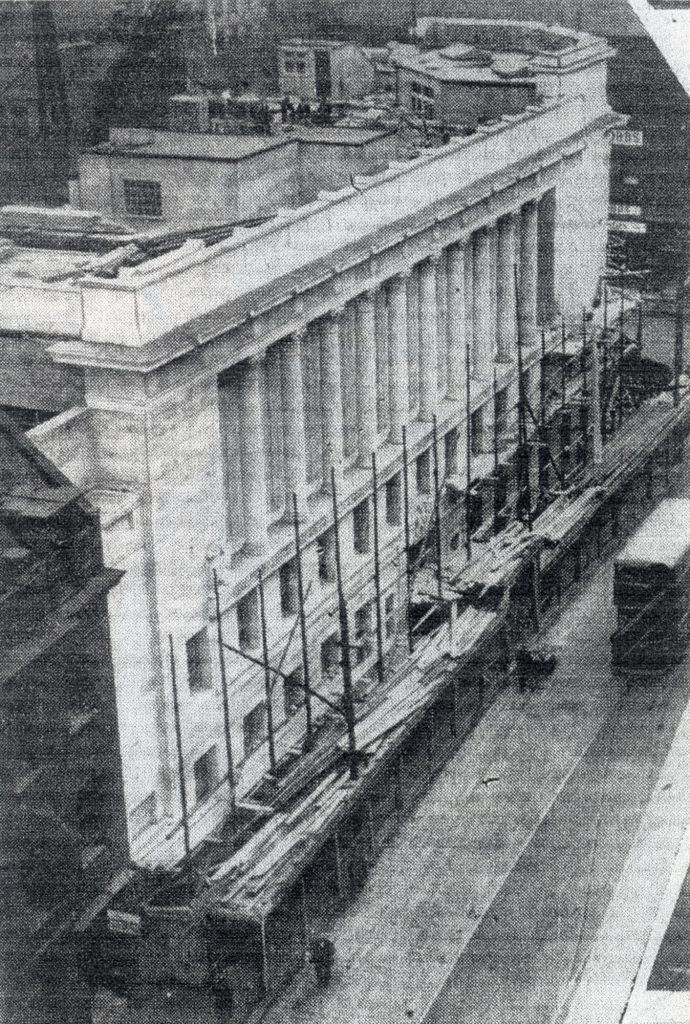

The imposing Pilgrim Street police, magistrates court, and fire station building, the work of local architectural firm Cackett, Burns Dick & MacKellar, is a central landmark in the new development. Built between 1931 and 1933 to replace a previous station, it was Grade-II-listed in 1999 and is earmarked for conversion to a five-star hotel.

Thomas Cackett & Robert Burns Dick contributed greatly to the appearance of Pilgrim Street; further up the road, they were responsible for the design of the stately Northern Conservative Club at 29 Pilgrim Street, near the Paramount cinema (later the Odeon). This was later demolished to make way for one of the city’s most-disliked buildings, Commercial Union House. Blame T. Dan Smith!

Robert Burns Dick enjoyed a larger-than-life reputation in his adopted home town of Newcastle. Born in Stirling in 1868, his family had moved south when he was very young and Burns Dick always regarded himself as a Geordie.

After attending the Royal Grammar School and art school, he moved through various architectural firms before entering into partnership with another Scot in Newcastle, Thomas Cackett. Burns Dick provided the creativity while Cackett looked after the business. The company went on to design many of Newcastle’s most important buildings, including the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle University Students’ Union building, the Pilgrim Street police and fire station, the Bridge Hotel, and the extension of the Northumberland County Council offices, now the Vermont Hotel. Away from Newcastle, Burns Dick was the man behind Whitley Bay’s recently-reopened Spanish City buildings and Berwick-upon-Tweed’s old police station (regarded by many as the model for the Laing Art Gallery). An advocate of the Garden City movement, in the 1920s he helped design west Newcastle’s low-rise, low-density and landscaped Pendower housing estate.

The Burns Dick (Robert) Archive

Our Burns Dick (Robert) Archive was collated after a 1984 exhibition about the architect, held by the Royal Institute of British Architects Northern Region. Although instrumental in the design of some of the area’s best architecture, it was felt that Burns Dick had been ‘forgotten’. The archive comprises photographs of Burns Dick and his family, two University dissertations about him, and a collection of press cuttings about Burns Dick and the exhibition. These provide a good overview of his life and outline some of his ambitious plans for Newcastle.

In 1924 Burns Dick was a founder member of the Newcastle upon Tyne Society to ‘Improve the Beauty, Health and Amenities of the City’. He advocated a green belt around Newcastle and drew up a list of city centre historic buildings to be saved from any future demolition or decay.

Newcastle’s pre-eminent Victorian architects, Richard Grainger and John Dobson, had created an architecturally beautiful city but its roads were designed for horses and carriages. Burns Dick, although appreciating the pair’s work, said,

‘Is not Newcastle still trading on the brains of Grainger and Dobson and Clayton? . . . It has done nothing since worth mentioning in the same breath.’

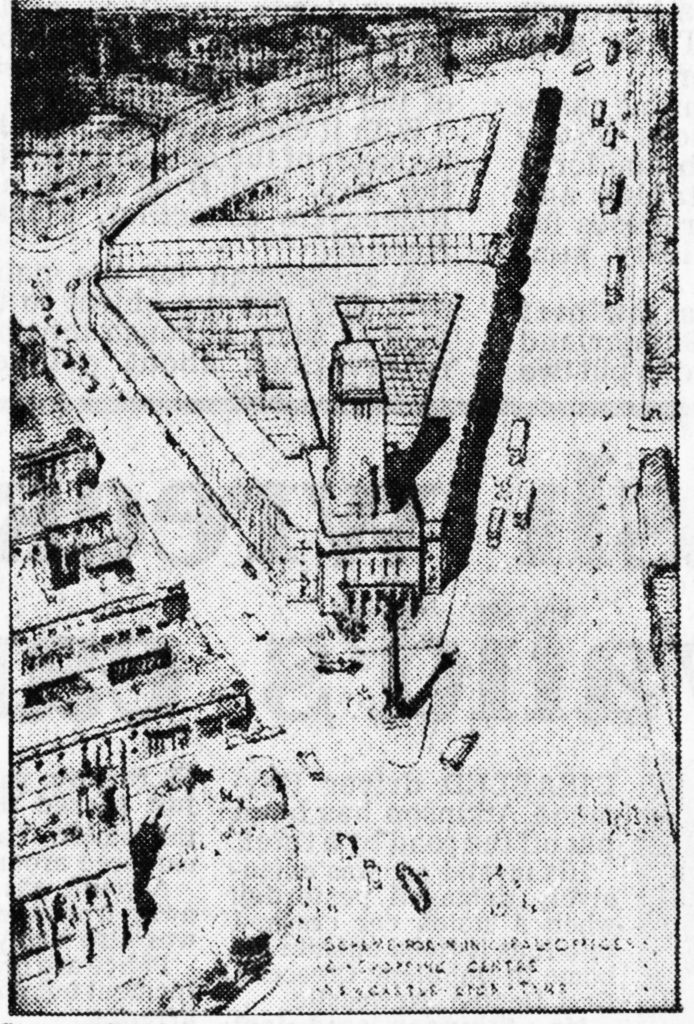

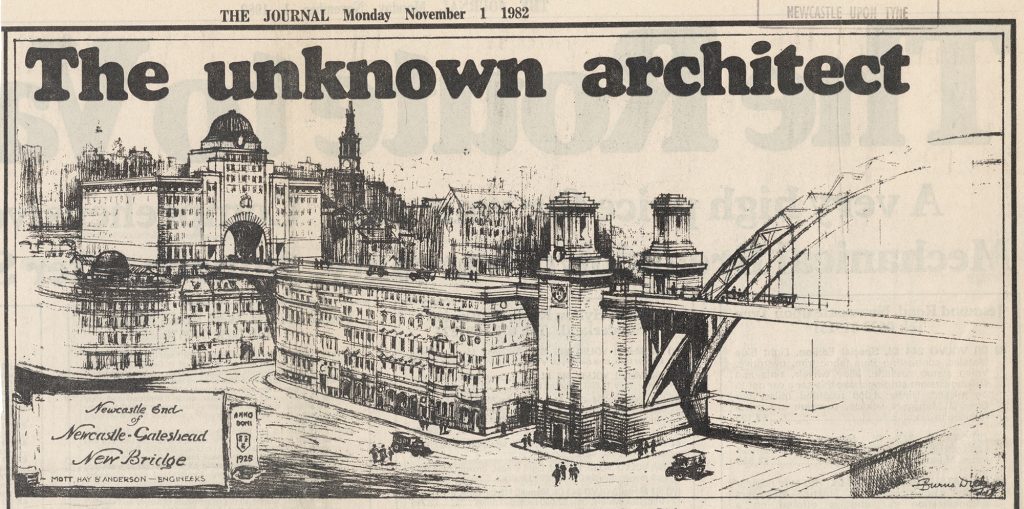

He drew up plans for new roads to accommodate the arrival and proliferation of motor vehicles in the city, including a development of his partner Cackett’s 1905 plan for a south to north axial road running from the new Tyne Bridge to Barras Bridge to the east of Northumberland Street, and then to his proposed civic buildings on a site near Exhibition Park.

Had Newcastle Council not suffered a funding shortage and a change in political power, Burns Dick’s plan for roads, and his grand entrance arch at the northern end of the Tyne Bridge, may have gone ahead. The arch would, of course, have led onto Pilgrim Street, which became the Great North Road (later the A1).

Maybe as compensation, Cackett & Burns Dick were handed the contract to design Newcastle’s new fire, police station and courts.

Burns Dick eventually moved to Esher, Surrey, and died there in 1954. His body was returned to Newcastle and he was buried in Elswick Cemetery.

In Newcastle, the city’s 1960s planners sat and planned a new north-to-south road running to the east of Northumberland Street. This was eventually opened in 1970 and named after one of the Newcastle’s Victorian architects, John Dobson.

T. Dan Smith, Leader of Newcastle City Council from 1960 to 1965 and the city’s ‘bogeyman’, is often credited with the destruction of Newcastle’s historic buildings and their replacement with ugly concrete blocks, even though much of what he is held responsible for was built after his period in office.