The month of October marks both World Architecture Day and World Cities Day (2nd and 31st October 2023 respectively). Not only that, but The Deep Aquarium at Hull is celebrating its 20th year of operation. With this in mind, Farrell project staff wanted to present some interesting features about aquariums that were built, imagined designs that never materialised and the ways in which they contribute to urban planning around the globe, based upon the material available within the Sir Terry Farrell collection.

Because who doesn’t love an aquarium?

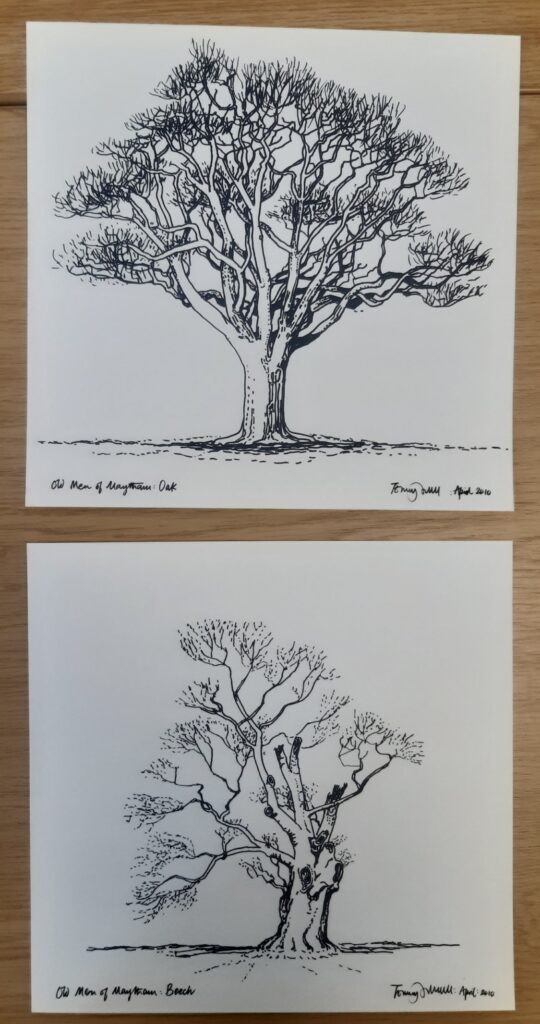

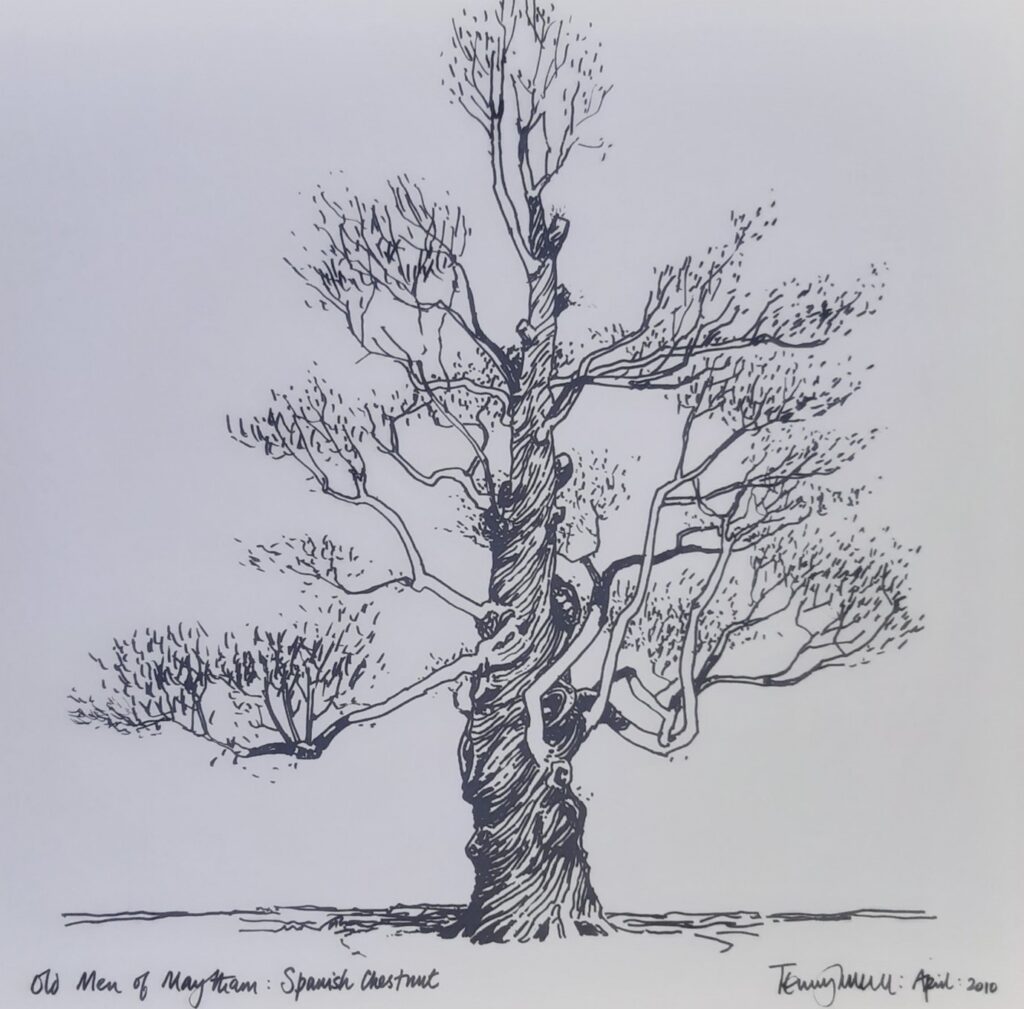

The Deep, Hull (1999-2003)

The aquarium provided the central focus of Terry Farrell and Partners wider masterplan for the city of Hull. The objective of the project was to provide a catalyst for the economic regeneration of the city and the location for the aquarium occupied a former shipyard.

In the final design, the building rises at an acute angle to form an angular point directly above the spit of land between the River Hull and the Humber Estuary. Exterior finishes were chosen for their ability to season over time whilst looking aesthetically pleasing. Cladding choices consisted of marine-grade aluminium and reflective ceramic tiles, suggesting fissured rock plates.

Visitor circulation within the building was also carefully controlled. Visitors entered the building and were elevated to the top floor before zig-zagging down in a continuous ramp through the various aquariums and interactive exhibits. The Deep stands out as a personal favourite Sir Terry Farrell and Partners attributed project.

But the real question is… does it look like a shark, a ship or an iceberg?

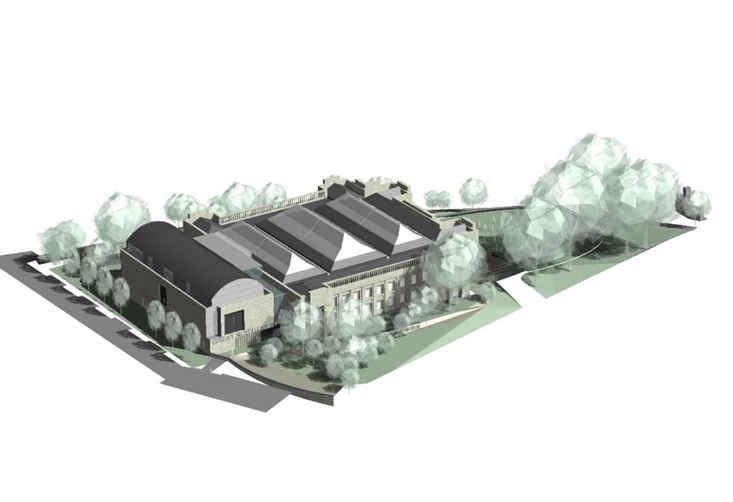

Biota Silvertown – London (1997-2009)

Whilst you may be lucky enough to visit The Deep, there is also material in the Sir Terry Farrell archive of aquarium designs that didn’t get the go ahead.

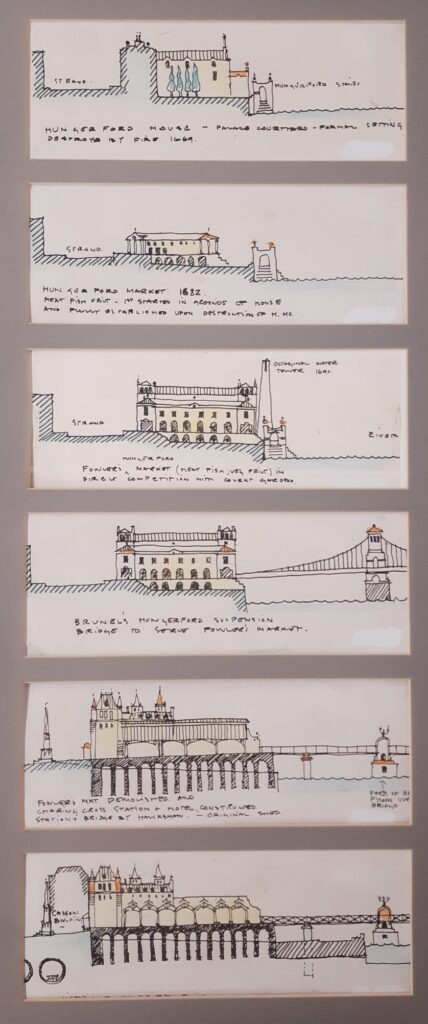

One of these proposals was the Biota! Silvertown Quays redevelopment, part of the Thames Gateway redevelopment region adjacent to Royal Victoria Dock, London. It formed one of the main public attractions on this site, which also included the Silvertown Venture Xtreme sport and surf centre.

Section and impression drawings of Biota! Item refs: TF-03798 and TF-03799

Biota was intended to be an aquarium based entirely on the principles of conservation, with each of the four biomes representing an entire ecosystem. The eventual building was given planning permission in March 2005 and was expected to be completed in 2008, but was unfortunately cancelled in 2009.

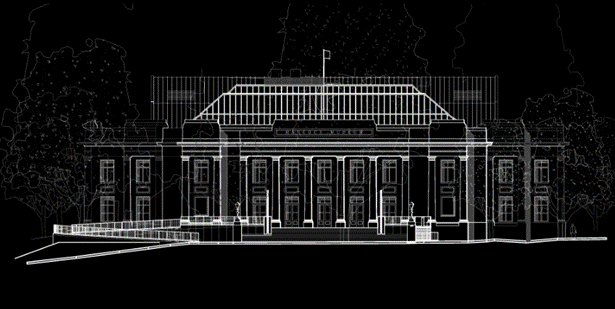

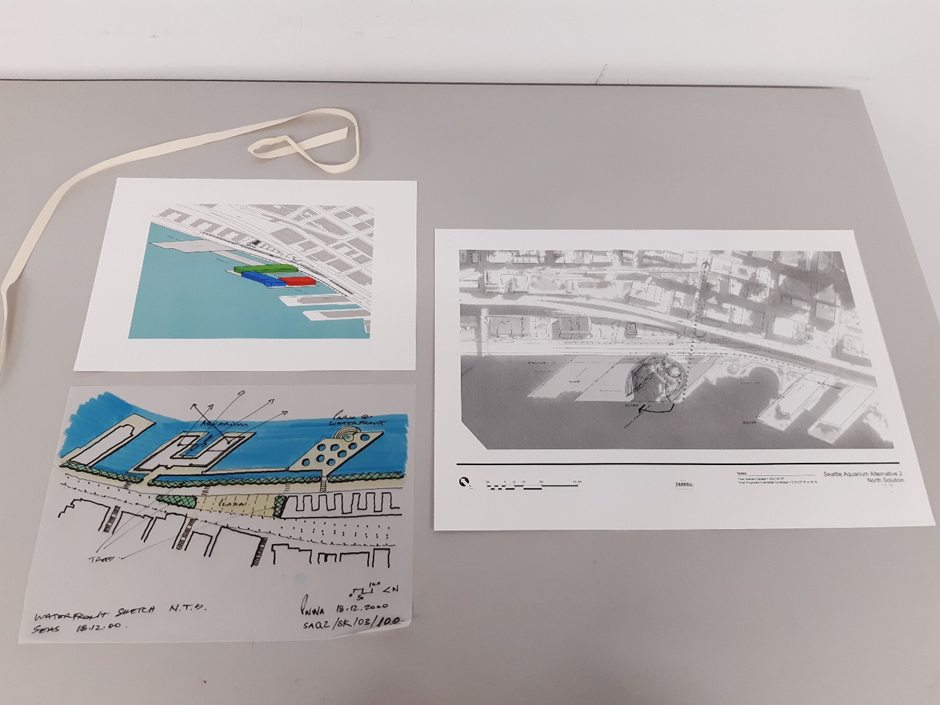

Pacific Northwest Aquarium – Seattle (1999-2001)

Moving across the Atlantic, pausing to marvel at what these man-made aquariums represent, we land at the design concepts for the Pacific Northwest Aquarium.

The Pacific North-West Aquarium sits on the waterfront at Elliott Bay in Seattle. It has occupied the site since 1977 and in 2000 Terry Farrell and Partners were invited to present a scheme with local partner architect Mithun to redevelop the aquarium across two pier arms numbered 62-63. The aquarium straddled two of the pier extensions, with one arm focusing on operational and administrative elements of the aquarium, whilst the other was used for public exhibits.

The shape of the aquarium was to resemble an open basin and contain a microcosm of ‘Puget Sound.’ It was intended to be an iconic structure in the Seattle landscape and hold a revamped exhibition programme. There appears to have been community opposition to the scheme due to its view-blocking appearance and future schemes did not involve Sir Terry Farrell and Partners.

Any Sir Terry Farrell archive related enquiries can be made to jemma.singleton@newcastle.ac.uk. Hope you make it to an aquarium near you soon for the buildings as well as the fishes.

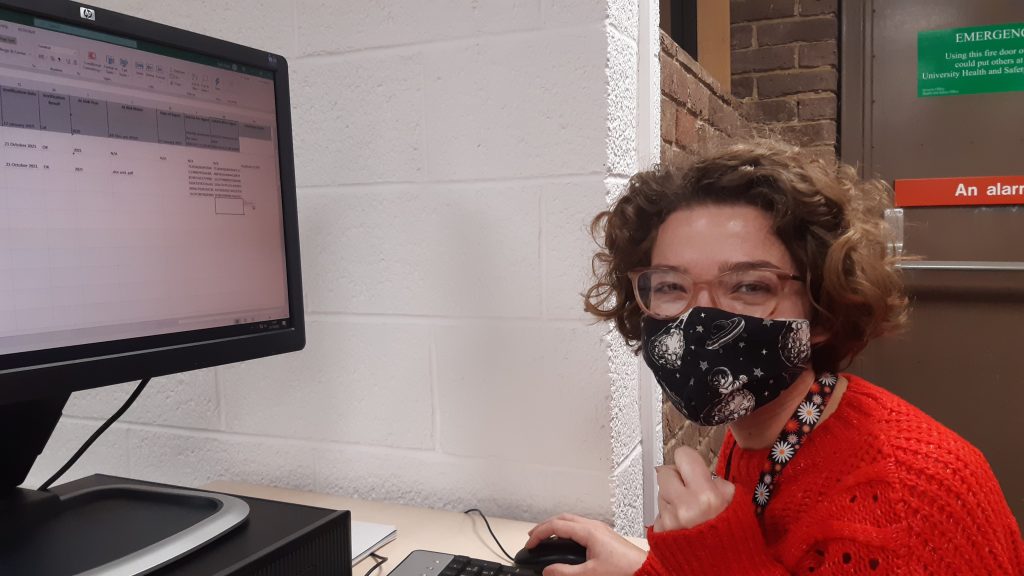

Sir Terry Farrell’s archive has been generously loaned to Newcastle University Library and is currently being catalogued. A catalogue is due to be made available to the public at the end of 2023. All rights held by The Terry Farrell Foundation.