Conduct literature is a little-known genre nowadays; it has been absorbed mostly into magazine culture and advice you get from your grandma. But in the 18th and 19th centuries it was a genre of literature that shaped, and was shaped by, popular culture. Conduct literature is texts that give advice on how to behave in polite society and how to run a successful household; in other words, on a person’s conduct. This advice ranged from the practical; how much credit it was acceptable to run up with household vendors; to the philosophical; how best to educate children to make them into functional citizens. The vast majority of these texts were aimed at women: in their capacity as mothers, as wives and as daughters. These manuals formed an influential industry in the late 18th and early 19th century as the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars raged and the British propaganda machine cultivated the idea of the French as immoral and dissolute compared to Britain’s steadfast morality. This deep-seated aspiration for ethical superiority is seen in the conduct literature of the age, conduct literature found in the 18th century collection at Newcastle University. As part of this collection the University holds books by Hannah More and Mary Wollstonecraft (among others), authors who, despite their varied political viewpoints, used their writing as a way of giving women more power.

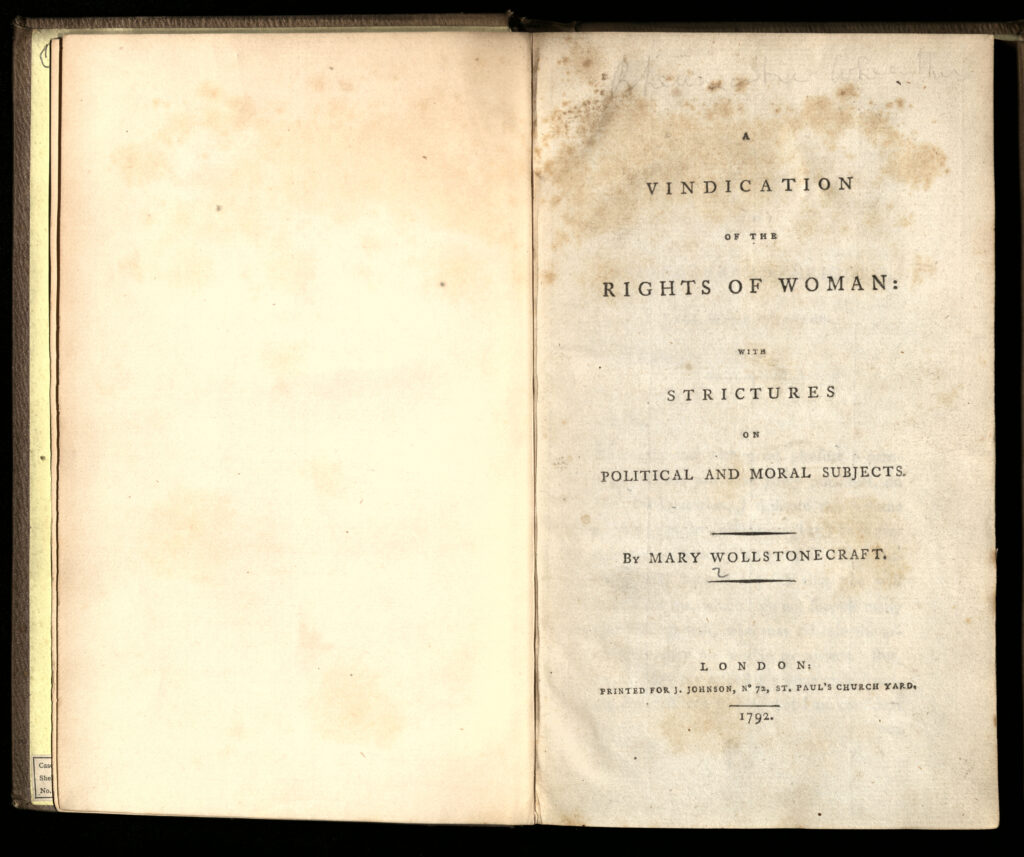

Mary Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), widely regarded to be one of the first works of feminist philosophy and the precursor to the organised feminist movement. A first edition of this is held in the 18th Century Collection in the Phillip Robinson Library, previously owned by Joseph Cowen, revolutionary Member of Parliament for Newcastle Upon Tyne. This manifesto for female education was a well-known, radical example of the conduct literature genre. Wollstonecraft famously wrote in her introduction to the volume: “My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.” (6, emphasis original). This sentence is a decisive judgement on both women and the men who interact with them. Wollstonecraft invokes rationality to justify the language of her doctrine; a characteristic that was considered the defining trait of humanity in the 18th century. She also implies that women were treated as being in a ‘state of perpetual childhood’ by men in this era, something that can be seen in the conduct literature written by men in the 18th century. For instance, in Fordyce’s Sermons for Young Women he states, “The Almighty has thrown you upon the protection of our sex. To yours we are indebted on many accounts. He that abuses you dishonours his mother. Virtuous women are the sweeteners, the charm of human life.” (9). Not only does Fordyce imply women to be incapable of functioning without male protection in this statement, but he also designates them as ‘the charm of human life’ thus suggesting them not to be human at all. This is where the different political viewpoints of the female conduct literature writers held in Special Collections at Newcastle are united. Although they differ in how it should be expressed and used, each author acknowledges the female capacity for rationality.

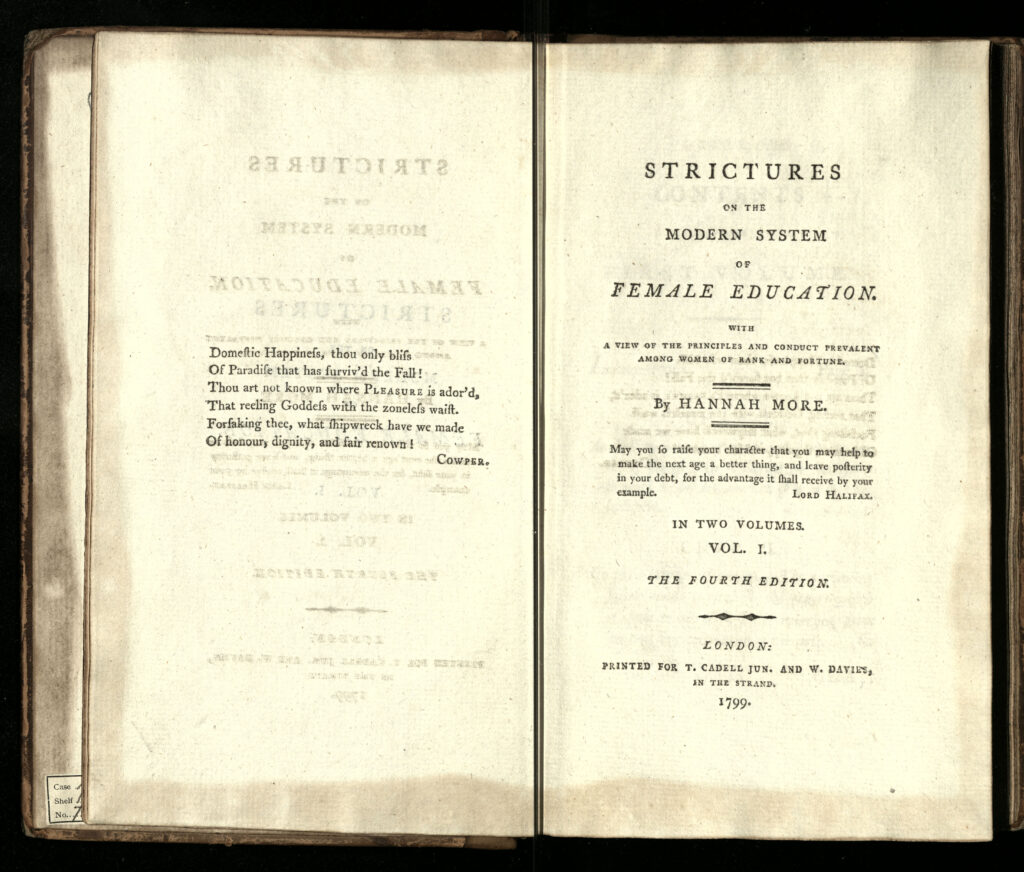

Another deeply influential text that is held in the 18th Century Collection at Newcastle is conservative moralist Hannah More’s Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (1799). This is one of many texts by Hannah More that is held by the university, but Strictures is her best well-known work. The text discusses both the practicalities and the moralities of raising children, especially young women. More grounds her philosophy in the importance of the family in raising future citizens and in shaping society. On the title page of the fourth edition copy held in the Newcastle University archives (shown above) she places a quote from Lord Halifax which states, “May you so raise your character that you may help to make the next age a better thing, and leave posterity in your debt, for the advantage it shall receive by your example.” This statement embodies More’s attitude to female morality and education; in Strictures she passes judgement on aristocratic women and their perceived indolence. More, like Wollstonecraft, values the emerging middle-class and their work ethic, manifesting in women through their cultivation of useful employment such as mending, rather than the frivolous, impractical embroidery typically undertaken by the aristocracy. When quoting Lord Halifax, More also invokes the concept of debt to a nation; she perceives women as being as much the cause of Britain’s intellectual superiority as men and as owing their full potential to their country.

The idea that citizens owe their nation morality stems from the conflict with France mentioned earlier; the prevailing opinion in Britain was that the French were immoral and prone to excess, and therefore one way in which Britain was superior to them was through their morality. This created an anxiety around female morality that both informed and was informed by the conduct literature genre, including those held by Newcastle University. Hannah More and Mary Wollstonecraft are two of the most well-known conduct literature authors from the 18th century and occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum. Nevertheless, they are united in their anxiety about female morality during this period and how any degradation of that would affect the nation at large. This collective anxiety eventually led to a societal idolisation of the middle class, whose ideology and ethics would come to set the standard for British society. Mary Wollstonecraft and Hannah More, therefore, form part of a genre that shaped British culture and therefore its history.

Written by bequest student Charlotte Davison, Postgraduate student from the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics.