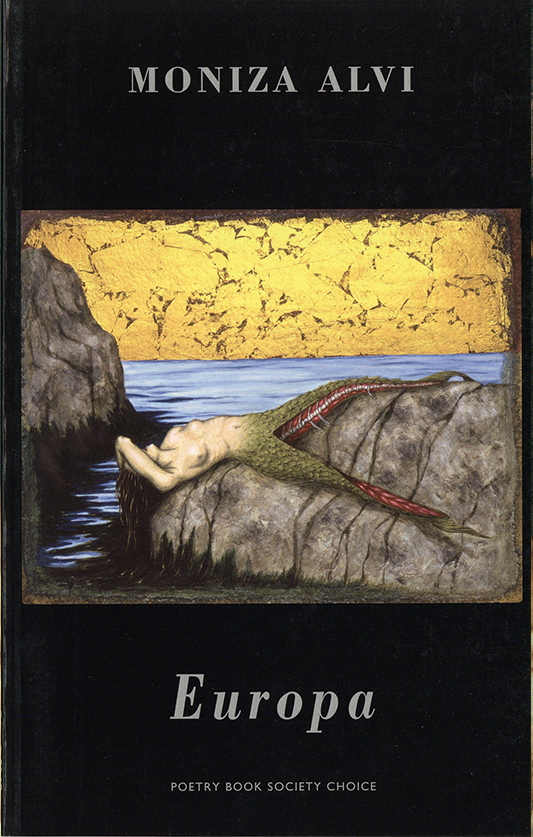

Flambard Press was a small-scale, independent, publishing press focused on new and neglected writers. It was started by Margret and Peter Lewis in 1990 and ran until 2012, supported by Arts Council England funding. This press was not a household name; they published their 129 books in small releases and focused on mostly northern authors whose work was otherwise neglected and unrecognised. Peter and Margaret worked out of the Phillip Robinson Library before moving the press to their home near Hexham, making a great deal of difference to the northern arts scene using less than £30,000 worth of funding a year. The two worked tirelessly and the Flambard Press archive at Newcastle University shows that Peter Lewis organised the printing of their books personally, including those published by his wife Margaret. They were involved in every aspect of their books’ publication, from editing, to cover design, to marketing – each aspect personalised and considered to get the best from the resources they had.

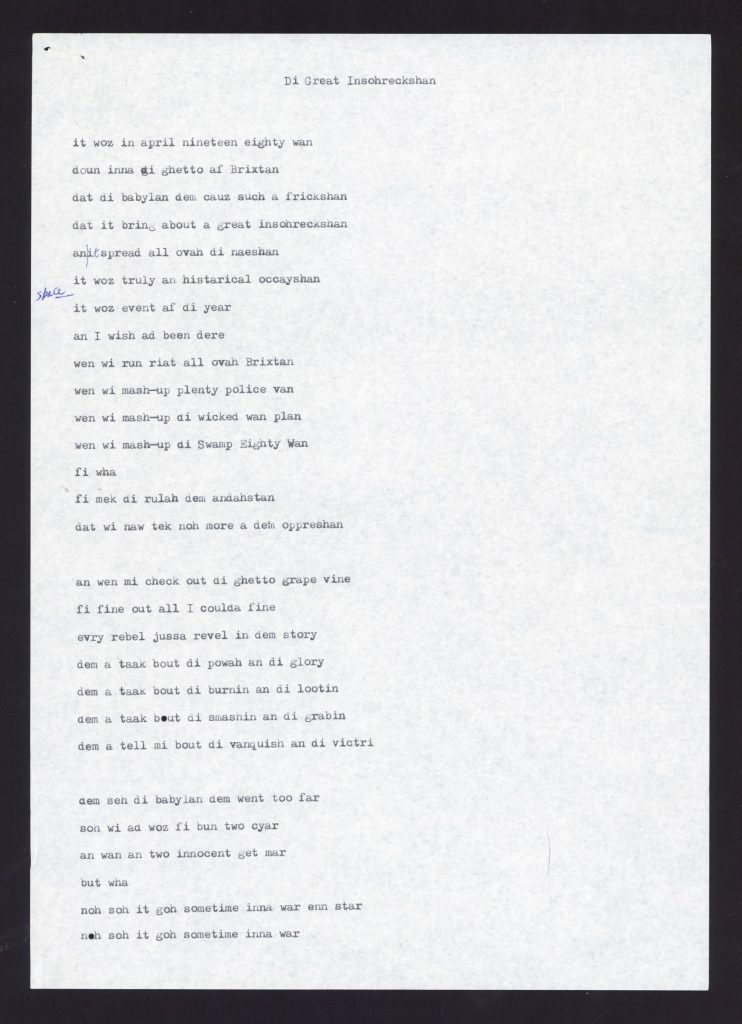

Despite the size and capacity of Flambard, they gained a great deal of recognition in their 22 years of operation. Their writers were nominated for the Booker Prize, the Whitbread Poetry Prize and the Whitbread First Novel Prize, among many others. The writers that Flambard worked with, though starting out unknown, frequently did not remain so. Many of the authors have become household names across the north of England and stretching out into the whole of the UK. Particularly notable is Neil Astley, now the influential editor/founder of Bloodaxe Books (founded 1978), whose patrons include Poet Laureate Dame Carol Ann Duffy and Chancellor of Newcastle University Dr Imtiaz Dharker. Another notable author published by Flambard Press is Val McDermid, prolific Scottish crime writer and winner of the Crime Writer’s Association Diamond Dagger in 2010; published her second collection of short stories Stranded with Flambard Press in 2005. Also, Courttia Newland, a British writer of Jamaican and Barbadian heritage who has been awarded the Tayner Barbers Award for science fiction writing and the Roland Rees Bursary for playwriting. These three authors are only a small sample of the depth and talent of the authors who worked with Peter and Margaret; because of their small capacity Flambard had to be selective with the writers they worked with and whose talent they would put their considerable talent and effort into. This critical judgement paid off with the press receiving recognition and awards well beyond its size.

Flambard Press inspired a loyalty in their authors that those who read the acknowledgements sections of mass produced books rarely witness. Rather than lukewarm statements thanking a corporate entity and switching from publisher to publisher with little ceremony; Flambard Press was a family. It was run by a family and its authors were taken into that family, without scruple. Although Flambard provided a jumping off point for many incredibly successful authors, it is the importance of the press to the more unknown authors that is so visible in the special collections archives. Kelly Swain, author of Darwin’s Microscope, said about Flambard when it closed; “Flambard Press made me believe I could do this writing thing. That I should do it. And I love them for that, and I feel a fierce loyalty to the press” (Farewell, Flambard – Kelley Swain (wordpress.com)). Similarly, Martin Edwards, another crime author in the Flambard roster, in his tribute to Peter Lewis on the event of his death on his blog, said about his book Dancing for the Hangman that it “didn’t make any of us a fortune, but I’m still proud of it”. This seems to be Flambard’s unofficial ethos, they didn’t search for funding from private donors or work under a cooperate umbrella; Peter and Margaret worked for the love of literature and for the betterment of northern writing. The Flambard outfit was small and content to remain so if it allowed writers that would not otherwise see the light of day to be recognised.

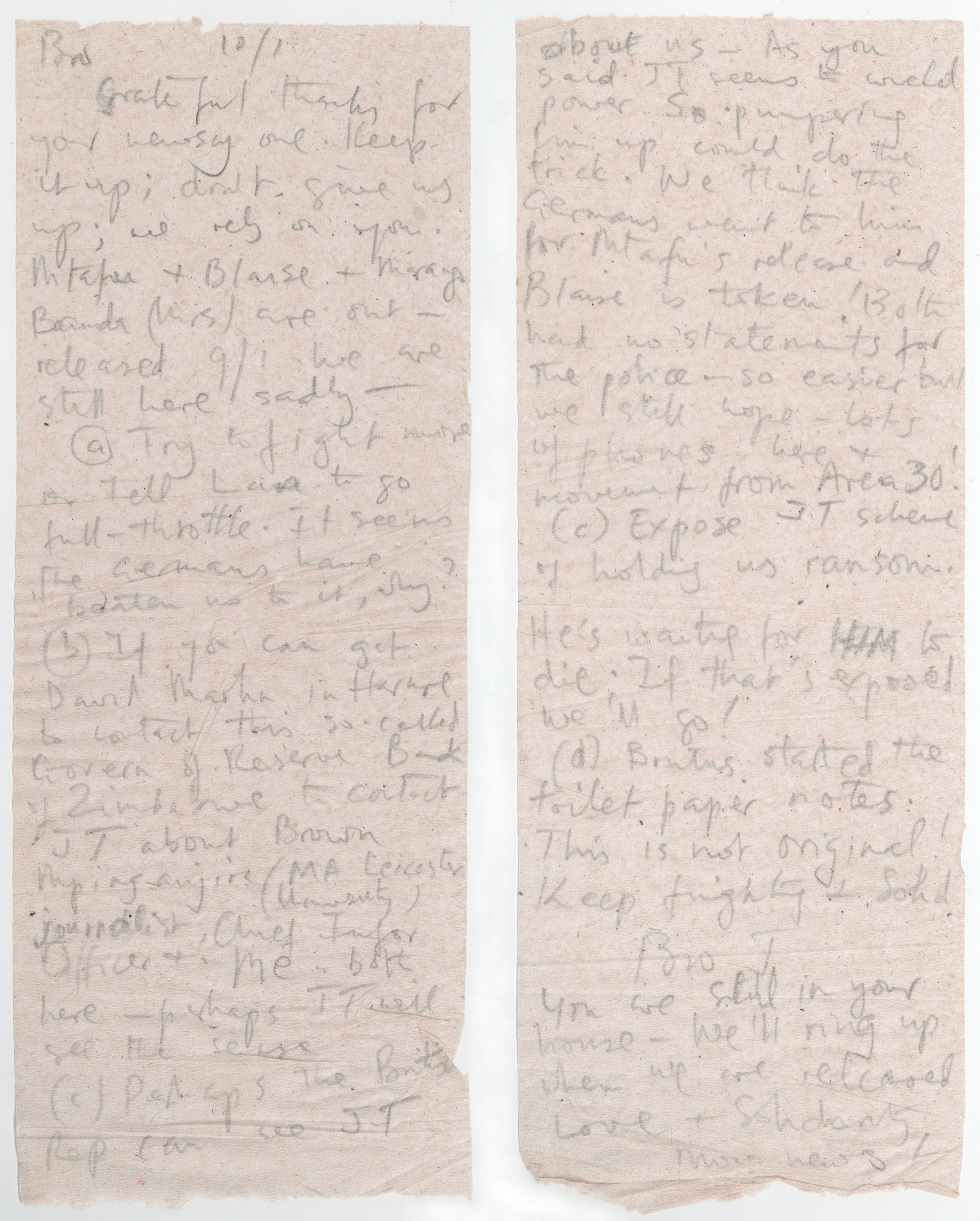

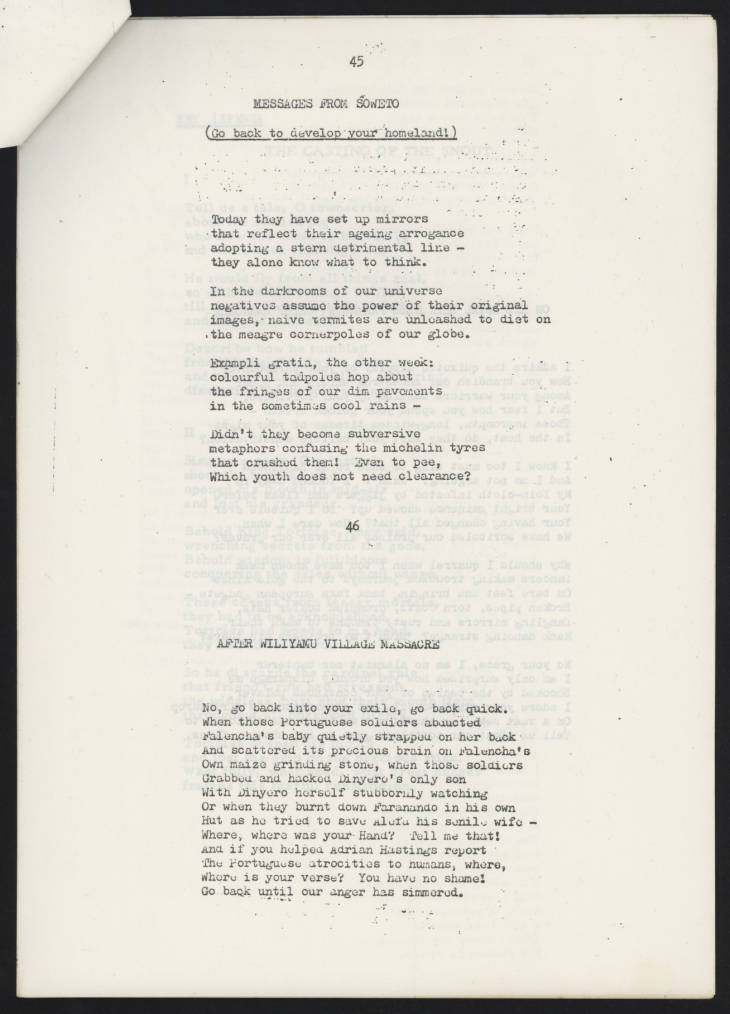

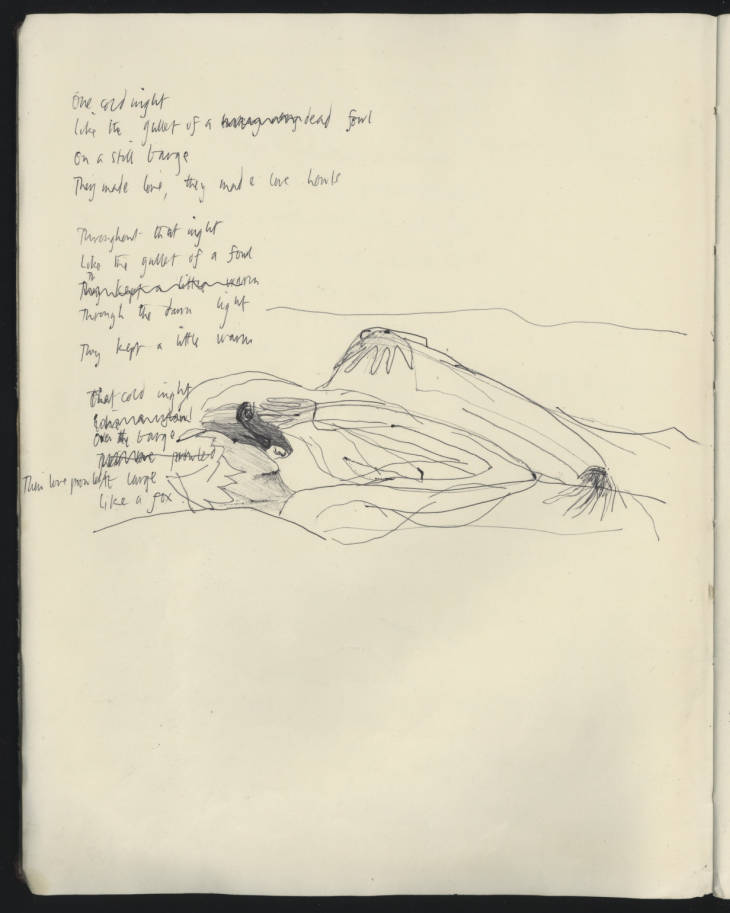

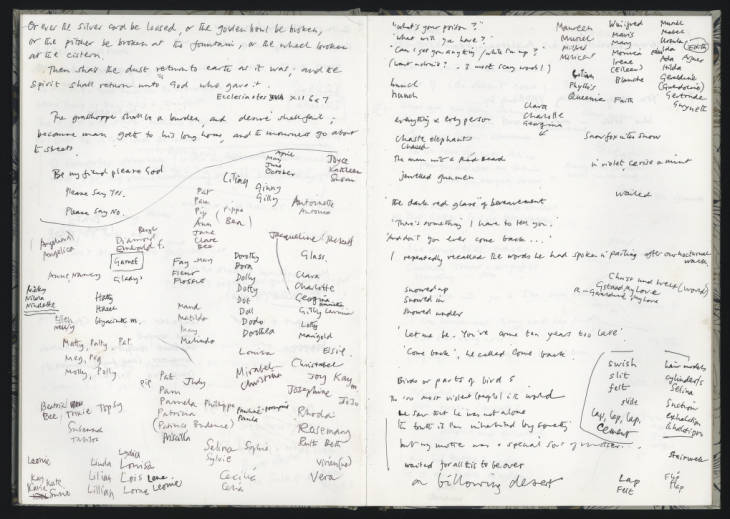

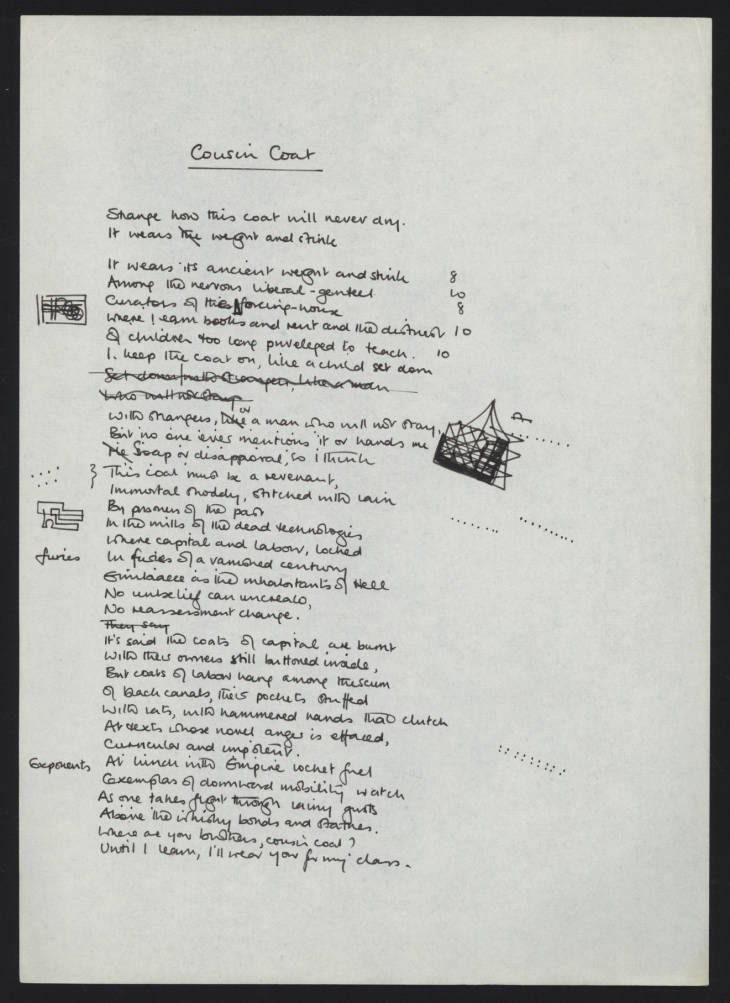

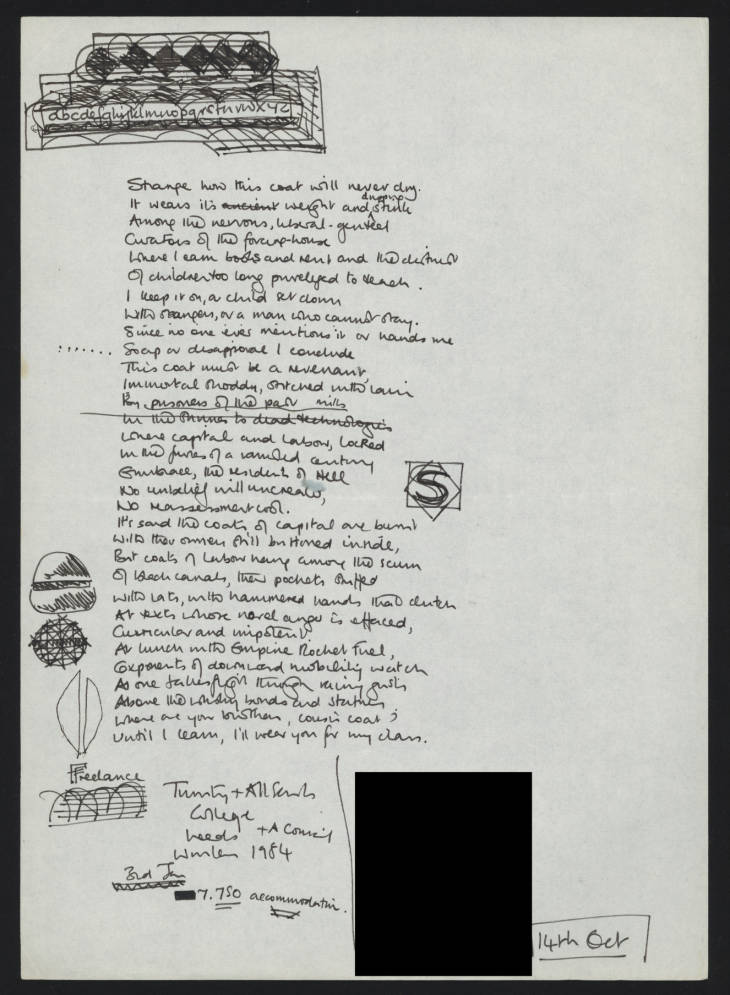

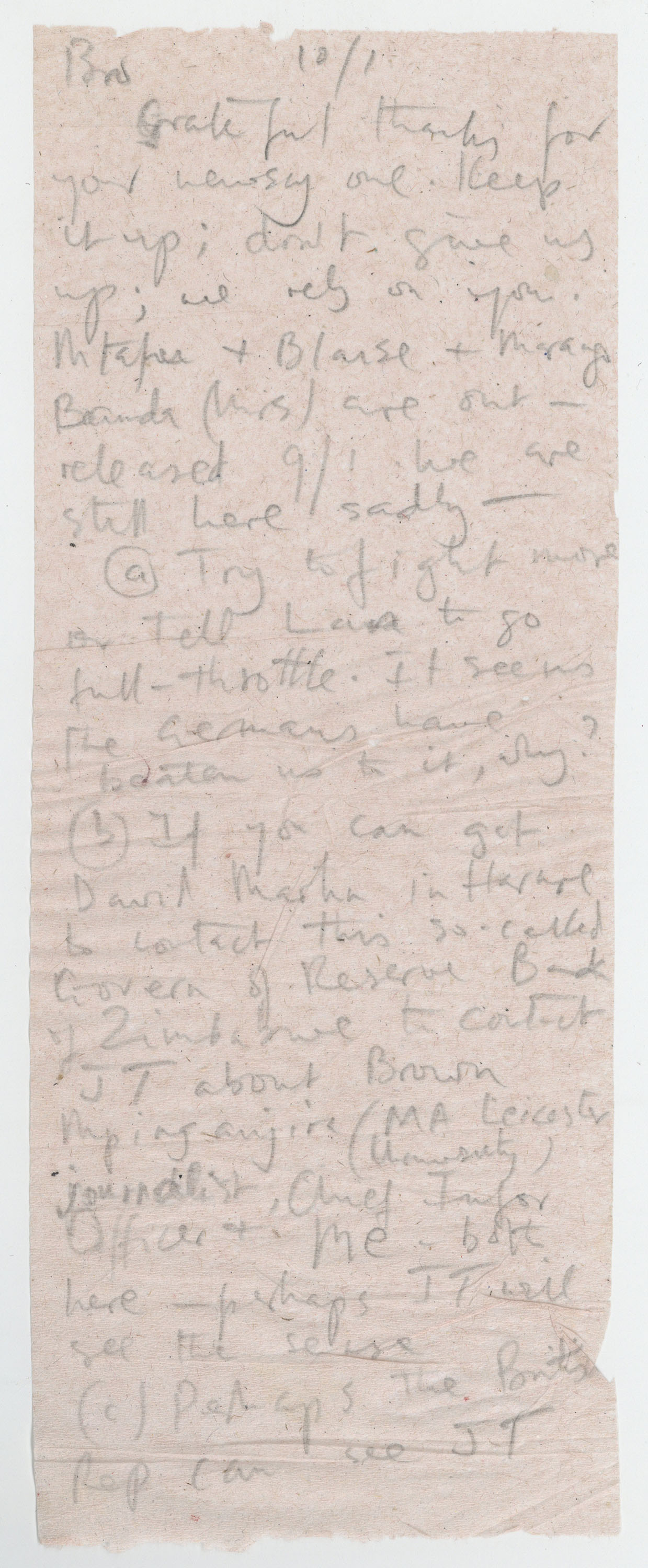

This family-oriented ideology makes for a moving experience when looking at the Flambard Press archives. After searching through files on individual authors; skim reading magazines with favourable reviews; and acknowledgements of prizes the Flambard family had won; by sheer luck the final file I looked at was one containing administrative documents for the company. An innocuous start, expecting a thin file with employee lists and financial documents, I was shocked when a full to bursting file landed on my desk, containing what appeared to be reams of letters and emails. This file, clearly lovingly compiled, by photocopying handwritten notes; taking extracts from magazines and printing off emails; contains the legacy of Flambard Press. The press dissolved unexpectedly in 2012 after their Arts Council funding had been reallocated elsewhere, and this was the response. Letter after letter, not addressed to Flambard Press or to ‘the editor’ as so many are; but to Peter, Margaret and Will (Mackie, the managing editor at the time) expressing their sympathy, sorrow and offering any kind of help they could possibly give the people of the press, as well as the press itself. This file contained testimony of the hope and kindness Peter, Margret and their employees had given the authors they worked with, the eloquently written tributes are too numerous to cite here but here is a selection:

“I just wanted to say again how good it has been to work with you over the last twenty years. The fact that you had faith in that first book set me on track and your support has been vital all along”

– Cynthia Fuller (Instructions for the Desert, Background Music and more)

“I can’t believe it. I saw a post by Simon Thirsk on FB and thought, well they’ll never do that. But they have.”

– Courttia Newland (A Book of Blues)

“Please pass on my grateful thanks to Peter and Margaret. They took Fear of Thunder on when no one else wanted it, and hopefully it’s various success have repaid their faith in it.”

– Andrew Forster (Fear of Thunder, Territory)

“I have appreciated being a Flambard poet. I want to express my sincere thanks for your dedication. It felt the perfect place to be a poet. The books were produced to the highest standards and the covers were inspiring.”

– Jackie Litherland (The Apple Exchange, The Work of the Wind, The Absolute Bonus of Rain)

The closure of Flambard did not go unnoticed outside of those who were directly affected by it; Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate at the time) mentioned Flambard by name in her poem ‘A Cut Back’. She wrote:

Three little presses went to market, Flambard, Arc and Salt;

(Guardian, 2011)

had their throats cut ear to ear and now it’s hard to talk.

A copy of this poem can be found in the Flambard archive; diligently highlighted; presumably by the person who compiled the file that is an eloquent lament to a northern icon.

The legacy of Flambard Press, and of Peter and Margaret Lewis, is contained in these archives, in the letters from well-wishers and, lastingly, in the books the Press created. Flambard did so much good with so little in the north of England, for writers that could not or did not want to publish using mainstream publishing houses. Their 129 titles will remain in circulation for many years, and the writers whose careers Flambard began, or made, will continue to create amazing fiction.

This blog post was written in memory of Peter Lewis (1937-2024) co-founder of Flambard Press.