Today marks the bicentenary of the birth of Florence Nightingale (12th May 1820) – famed for her work improving sanitation and reforming nursing. Her importance to modern health is still recognised. To coincide with this anniversary the World Health Organization named 2020 the international year of the Nurse and Midwife. Roles we are certainly celebrating in the current pandemic today.

Much of the discussion of Nightingale relates to her work in the Crimea and the improvements she made to nursing – you can read more about her role in this previous treasure. However she was also instrumental in influencing sanitation improvements within the military more widely.

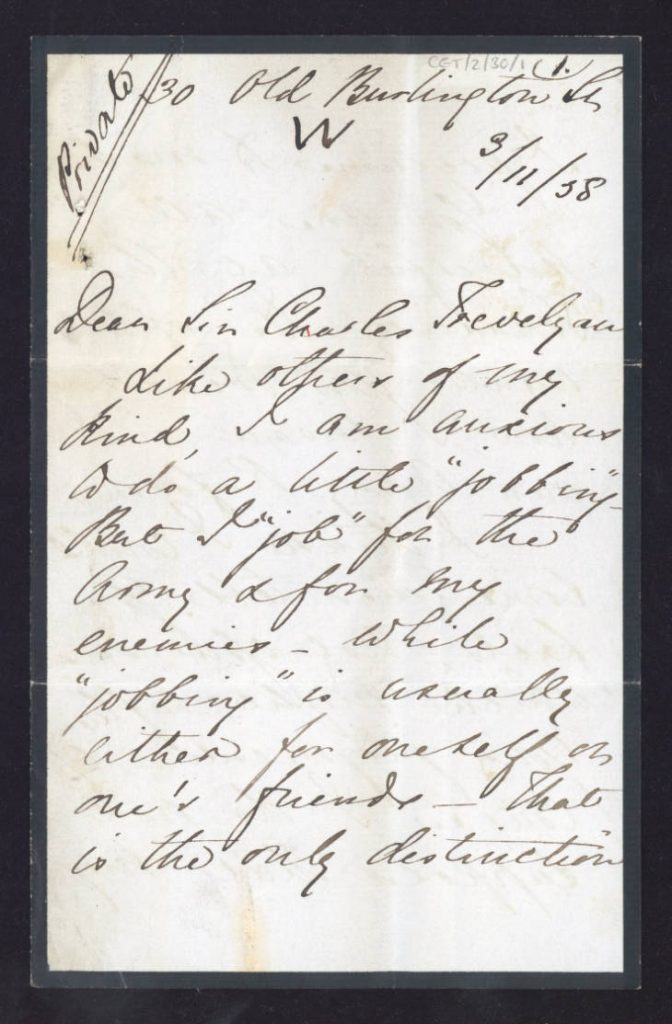

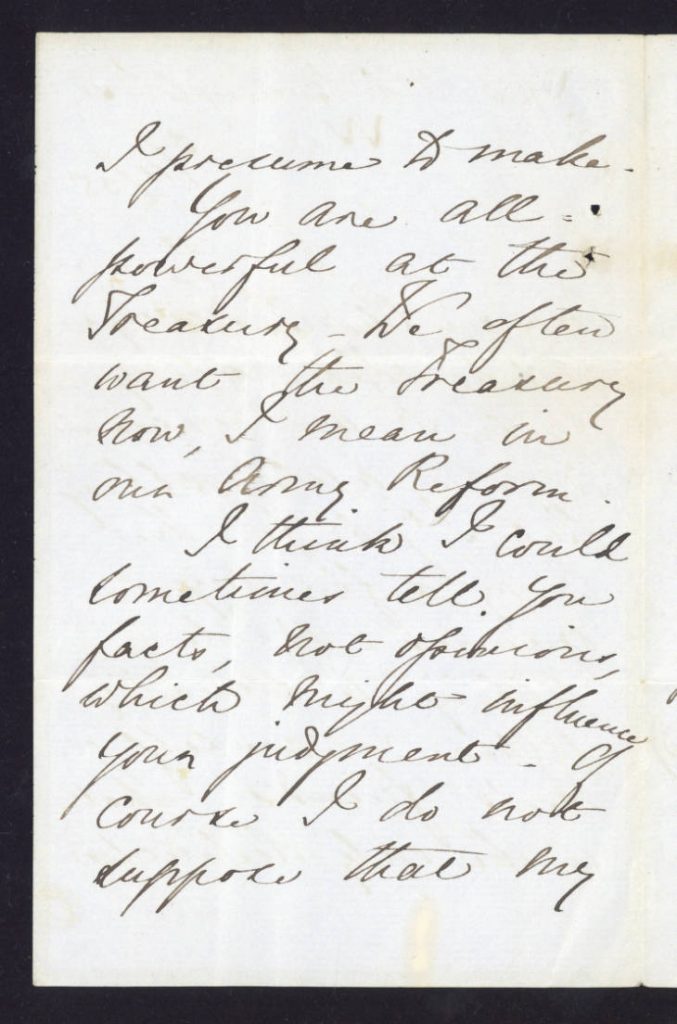

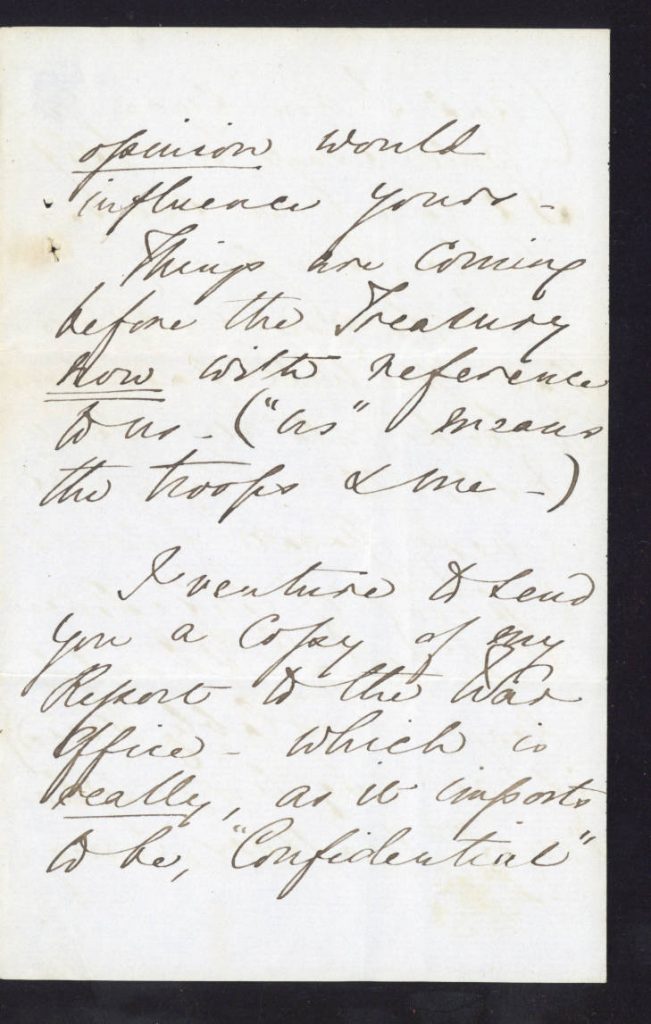

Nightingale did this by using her experience and knowledge to influence those with the responsibility for making decisions on military policy. This letter below

(CET/2/30/1) from the Charles Edward Trevelyan archive, dated 3/11/58, is one of a file of correspondence from Nightingale to Charles during his roles as Governor of Madras and financial member of the Indian Council at Calcutta. In the first, Nightingale tells Charles that she is ‘anxious to do a little “jobbing”’, meaning that she intends to turn her influence for gain, although rather than gains for herself, Nightingale ‘”job[]s” for the army + for my enemies’. The letter offers to share ‘facts’ with Trevelyan which may influence decisions made in relation to military policy. Visit CollectionsCaptured see larger images of the letter.

Transcription of letter from Florence Nightingale to Charles Philips Trevelyan (CET/2/30/1):

Private

30 Old Burlington

W

3/11/58

Dear Sir Charles Trevelyan

Like others of my kind, I am anxious to do a little “jobbing” but I “job” for the army + for my enemies – While “jobbing” is usually either for oneself or one’s friends – that is the only distinction I presume to make.

Florence Nightingale

You are all powerful at the Treasury. We often want the Treasury no, I mean in our Army Reform.

I think I could sometimes tell you facts, not opinions, which might influence your judgement. Of course I do not suppose that my opinion would influence yours.

Things are coming before the Treasury now with reference to us. (“us” means the troops + me).

I venture to send you a copy of my Report to the War Office – which is really as it imports to be, “Confidential” (and I am sure you will keep it so).

It is in no sense public property.

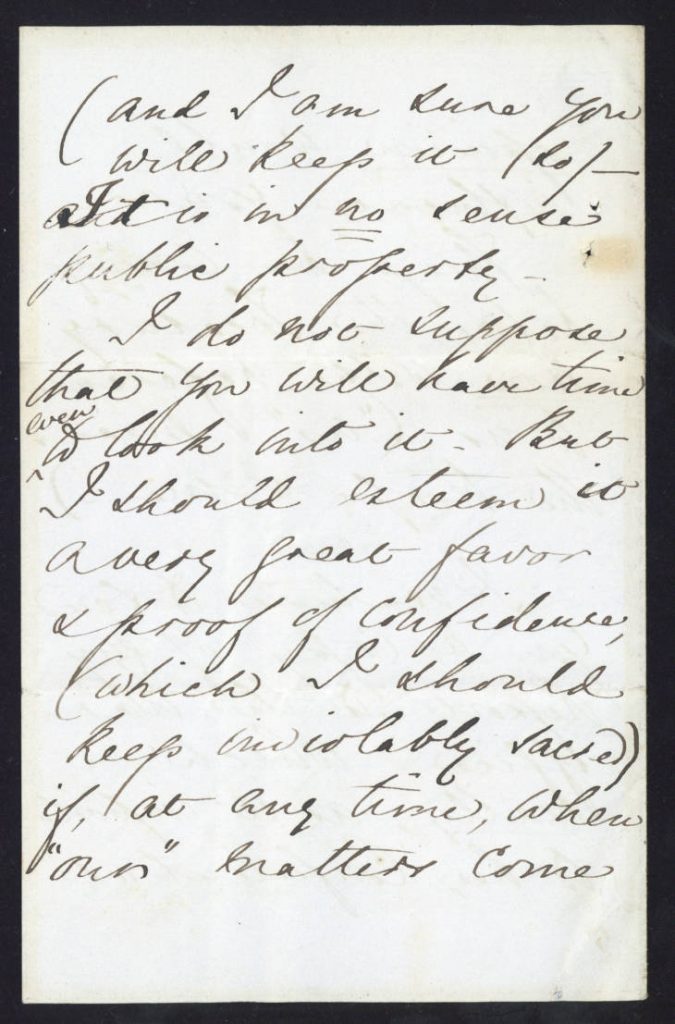

I do not suppose that you will have time [even] to look into it. But I should esteem it a very great favor + proof of confidence (which I should keep inviolably sacred) if, at any time, when “our” matters come…

The confidential report which was included is no longer present, but it was likely Subsidiary Notes as to the Introduction of Female Nursing into Military Hospitals. Unfortunately, the letter is incomplete, but it remains valuable evidence of Nightingale reaching out to influential figures to achieve her aims.

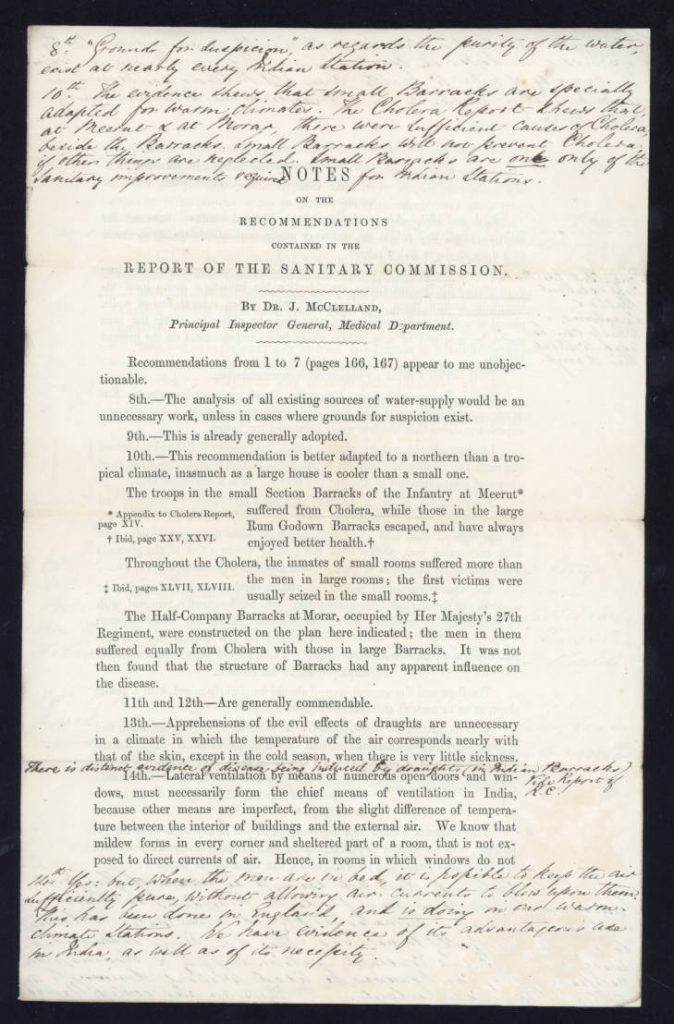

Nightingale’s influence on health in the British Indian Army continued. In the 1860s she collected information for The Royal Commission on the Sanitary State of the Army in India. In addition to the publication of the Commission’s final report in 1863, Nightingale published her own response, which can be viewed online.

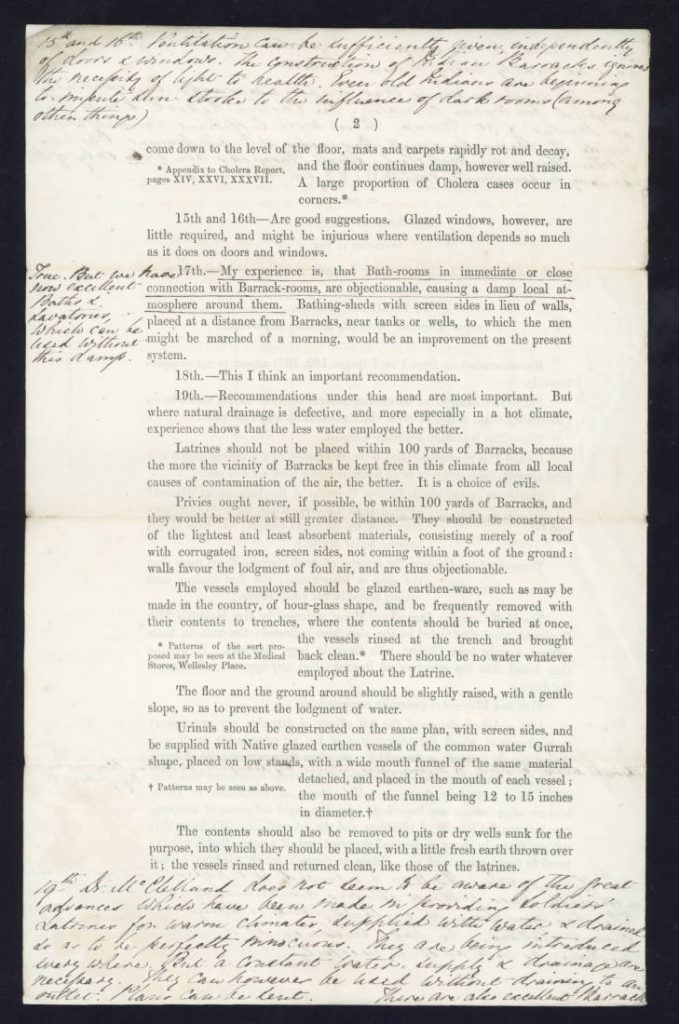

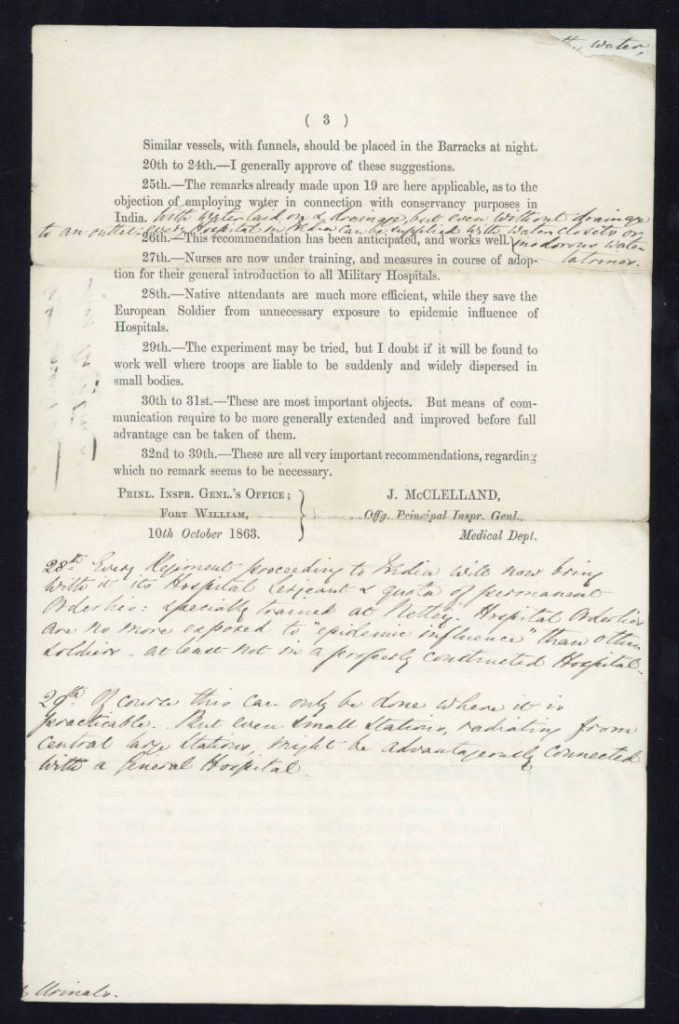

The file of correspondence from Nightingale to Trevelyan also includes a copy of printed notes on the official report’s recommendations by the principle inspector general of the Medical Department, Dr J McClelland (Trevelyan,

CET/2/30/10). Nightingale has annotated these, highlighting inaccuracies and providing additional information, likely with the aim of influencing Trevelyan’s actions (see below – find larger images on CollectionsCaptured).

Trevelyan, and the role of British colonialism in India are controversial and contested histories. Nevertheless, while governor of Madras Trevelyan did instigate improvements in local sanitation, possibly as a direct result of Nightingale’s influence opinion would influence yours.