This year World Architecture Day falls on 03 October 2022, and, as one of the cataloguers of the Sir Terry Farrell archive it seems fitting to write another blog where we can revel in some of Sir Terry’s interactions with listed buildings and the conservation process.

If you spend a small portion of your day indulging in architecture news to keep abreast of current trends… just me then… a key theme that crops up is a concern, maybe an aversion, towards redesigning listed buildings. The reasons for this aversion include, but are not limited to, the protective legislation around listed buildings of various grades and the extent to which, or how, they can be extended and modified. Restrictions may relate to the types of materials used, styles emulated, and building techniques required, not to mention which local authority is involved. It’s a heady mix to comprehend, regardless of if you are an architect wanting to demolish a listed staircase, or a member of the public who wants to refurbish their home.

Never-the-less, architects willing to engage with the listed building planning and application process do exist and Sir Terry Farrell was one of them. He appears to have been very engaged with the redevelopment opportunities afforded by listed buildings, and developed innovative solutions to satisfy building inspectors, local planning authorities, clients and contractors. Sir Terry Farrell appears to have had logical reasons for preserving listed buildings: if a building is still serviceable, why destroy it. The reasons are also sentimental: architects should respect rather than erase what they find on the ground because buildings are containers for lived experience and memory. By repairing and modifying the original fabric of the building, as an architect you contribute to the tapestry of living history.

Grey Street – Newcastle-upon-Tyne

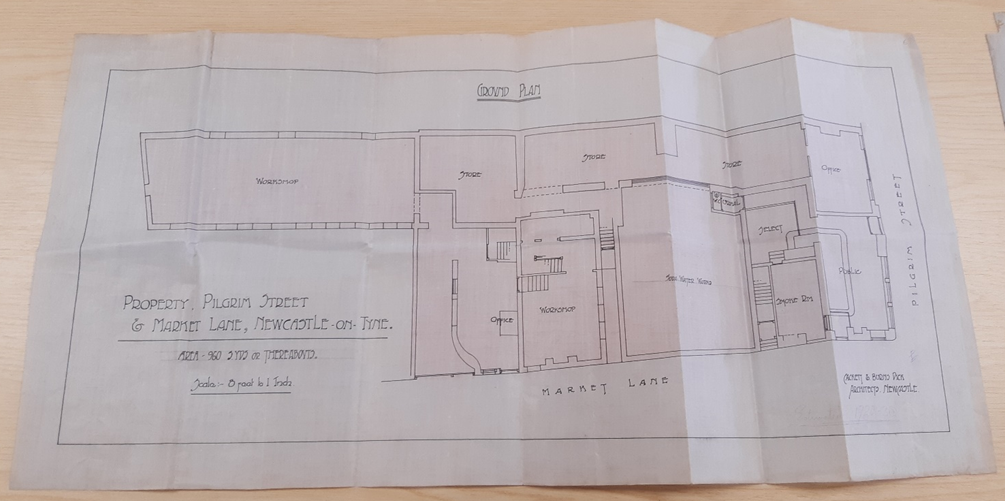

To start, something a bit local to Central Newcastle; the refurbishment of Grey Street. 52-78 Grey Street was designed by John Dobson for Richard Grainger in the 19th century (c. 1836) and is currently situated within the Central Newcastle Conservation area with a Grade II listed status. In 1995 Newcastle City Council approved a scheme by Terry Farrell & Company Architects in which Numbers 52-60 were restored and extended to the rear and the facade of Numbers 62-78 was retained to provide a frontage to a new open plan office space. Early planning applications included an archaeological survey, and the Sir Terry Farrell archive holds an array of earlier material detailing historic research and early building use plans. There are also some examples of pre-existing interior detailing that are not just random pieces of wood.

Most of the external façade of Grey Street had to be retained during the redevelopment; however, the internal reconfiguration was extensive, improving access throughout 52-78 Grey Street and redesigning the courtyard spaces between High Bridge Street and Market Lane. So, whilst the external appearance of Grey Street looks unaltered, the internal layout has been greatly changed. Just something to consider next time you are off on a stroll from Grey’s Monument.

The Royal Institution – Albermarle Street, London

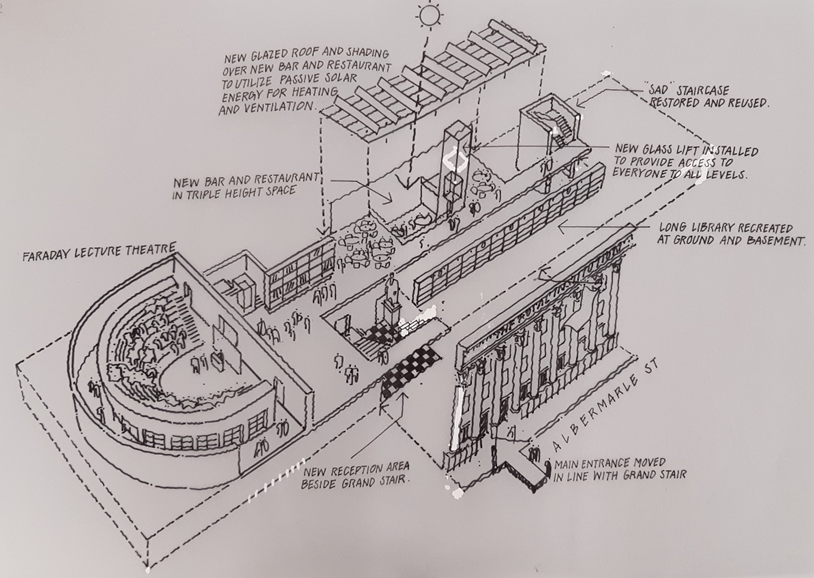

The Royal Institution was founded in 1799 and is based in a row of houses designed by John Carr and built in 1756. A later façade was added to the front of the terrace in 1838 by Lewis Vulliamy. The rooms behind remained largely in their original layout; they were poorly connected and, by the 1980s, were also run-down and confusing to visiting members of the public. Rodney Melville and Associates were initially tasked with conducting an Impact on Heritage Assessment which influenced the refurbishment plans based upon the Grade I listed status of elements of the building. These listed elements included the external façade, main staircase, lecture theatre, and ‘Conversation Room.’

Terry Farrell and Partners were selected as architects for the redevelopment of the Royal Institution project which ran from 1999-2008. In the final design, circulation routes were reinvented and the difference between public and private spaces clearly demarcated. The aim was to create clear horizontal and vertical connections and, at the same time, re-allocate what had become a jumble of different functions to logical defined spaces. The result was a ground floor of interconnected public spaces, with a basement level public exhibition space largely focused on the Young Scientists Centre, a first-floor lecture theatre and library suite, whilst third floor offices and laboratories were located on the top floor. The director’s flat was changed from the second floor to the fourth floor, replacing the caretaker’s flat. The listed ‘Sad’ staircase nearer the rear of the building was refurbished and extended to the lower ground floor.

Key to the straightforward zoning was provided by a rehabilitated rear courtyard of workshops which formed an atrium, and a new central lift component was installed and glazed over. This project demonstrates how extensive structural changes can be made within a listed building whilst appreciating its existing fabric.

Tobacco Dock Shopping Village – Wapping, London

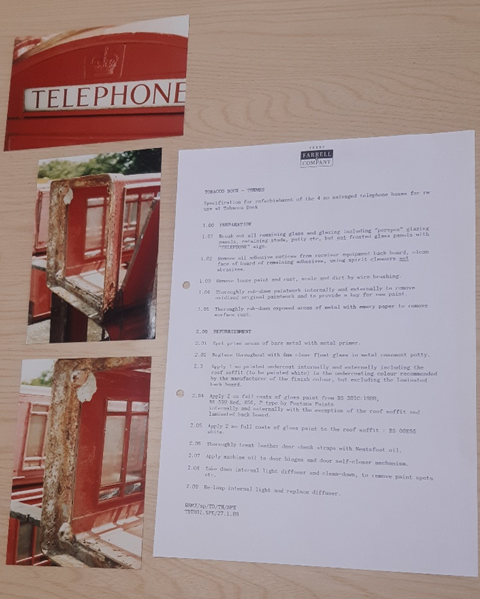

This project comprised the restoration and conservation of a significant historic Grade 1 listed dockside building dating from 1818, representing part of the early 19th century expansion of London docks. The project lasted from 1985-1990 and was completed in 2 parts; the first being the restoration of the original building fabric, and the second part involved the insertion of shopping and entertainment facilities and rebuilding the original dockside.

Restoration methods included the repair and the replacement of missing sections of the warehouse structure with fragments of the same type from buildings of adjoining sites which were threatened with destruction. Material from the archive demonstrates how remnants of industrial heritage around London influenced the finished appearance of the Tobacco Dock, and provide minutely detailed instructions for the refurbishment of salvaged material.

There is also evidence of the ingenious decisions made to protect the existing structure of the building, such as retaining sub-soil moisture to prevent timber supports from drying out by discharging rainwater pipes below the basement floor.

As the above projects demonstrate, the archive of Sir Terry Farrell is full of material detailing how listed buildings can be sensitively repaired, retained and modified for their overall improvement. Unfortunately, there is no time to share evidence of the extensive communication that occurs with the planning application process of a listed building or conservation area. However, if you are interested in research matters relating to building conservation or other architectural interests within the Sir Terry Farrell archive you can contact the cataloguing project team, either Jemma Singleton at jemma.singleton@newcastle.ac.uk or Ruth Sheret at ruth.sheret@newcastle.ac.uk who will be happy to assist.

Sir Terry Farrell’s archive has been generously loaned to Newcastle University Library and is currently being catalogued. Once catalogued it will be made fully available to the public. All rights held by The Terry Farrell Foundation.