The ancient Greek Olympic Games can be traced back to 776 BC although their exact origins are obfuscated by myth and legend. Dedicated to the Greek gods, they were staged in Olympia, in north-western Greece. Olympia was a place of worship and politics and home to temples, shrines and a great statue of Zeus. The statue was one of the seven wonders of the Ancient World, but it is thought to have been either destroyed or moved and then broken-up, by the Romans.

The Games were usually held every four years, or Olympiad, and all free men who could speak Greek were eligible to compete in the small number of events. Athletes usually competed nude; the Olympics was a festival celebrating the achievements of the human body. An ‘Olympic Truce’ ensured that athletes could travel from their countries to the Games in safety. Victorious athletes were honoured with wreaths of laurel leaves, hymns and feasts and their achievements recorded. The ancient Games continued for twelve centuries, until 394 AD, when they were suppressed for being pagan by Emperor Theodosius I, as part of his campaign to impose Christianity as a state religion.

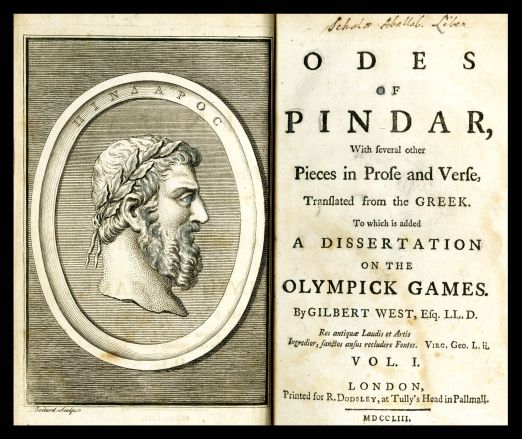

This title page is taken from Odes of Pindar, written by the Theban poet in the 5th century BC. Pindar was one of the most renowned poets of his time and the Odes are the only pieces of his work that survive intact today. He composed the words and music of over forty odes that were performed in celebration of the winners of different events at the Olympics and other ancient Games. Pindar’s Odes are beautiful but complex, difficult to translate from ancient Greek, and often hard for 21st century readers to understand and appreciate.

Pindar compared the achievements of Olympic victors to those of the great Greek Gods – believing their superhuman sporting deeds to be almost divine. Pindar’s poems do not describe in any detail what actually happened at the Games; his poems are about victory and the acclaim associated with winning. Athletes who had been victorious at the Games often commissioned an ode from a poet, for a considerable sum of money. The clients were rich aristocrats who saw the songs as ways of announcing their victories to the whole Greek world and ensuring their achievements would be long-remembered. Unsurprisingly, rumours of rich families ‘buying’ victories at the Olympics were rife.

In the first Olympick Ode, which was dedicated to Hiero of Syracuse, who in the 73rd Olympiad was victorious in the Race of Single Horses, Pindar writes:

‘Then for happy Hiero weave

Garlands of Aeolian Strains;

Him these Honours to receive

The Olympick Law ordains.

No more worthy of her Lay

Can the Muse a Mortal find;

Greater in Imperial Sway,

Richer in a virtuous Mind;

Heav’n O King, with tender care

Waits thy Wishes to fulfil.

Then e’er long will I prepare,

Plac’d on Chronium’s sunny Hill,

Thee in sweeter Verse to praise,

Following thy victorious Steeds;

Is to prosper all thy Ways

Still thy Guardian God proceeds.’

For the 2012 London Olympics, Dr. Armand D’Angour, a lecturer in Classics at Oxford University, has been invited to compose an ode by the Lord Mayor of London, Boris Johnson. An expert in the composition of ancient Greek verse, D’Angour also wrote an ode that was read during the closing ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympics.

This is the third time that the modern Olympic Games have been held in London – the 4th games were held in 1908 and the 14th in 1948. The games had been cancelled in 1944 due to the Second World War. When they were finally held in 1948, they became known as the Austerity Games due to continued rationing and tight post-war budgets, in contrast to this year’s £2billion extravaganza.

Although the modern Games were inspired in part by the ancient Games, they also have their roots in the Wenlock Games, which are held annually in Much Wenlock, Shropshire. Dr William Penny Brookes established the Wenlock Agricultural Reading Society in 1841 to provide an opportunity for local, working class people to acquire knowledge. He then created an Olympian Class in 1850 to encourage people to keep fit by training and competing in sporting competitions at the annual Wenlock Olympian Games. After meeting Pierre de Coubertin, a French educationalist who shared his belief that physical exercise could help prevent illness, he invited him to stay in Wenlock. Inspired by the Wenlock Games, Coubertin went on to set-up the International Olympic Committee in 1894, which organised the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. They have taken part almost every four years since.