The Spence Watson/Weiss Archive consists, for the most part, of letters they received, which are evidence of their involvement in both local and national matters of politics, education and society. They were visited by politicians, reformers, artists, writers and diplomats.

Included amongst the papers are a box of photographs of well-known figures such as William Morris, David Lloyd George and Myles Birket Foster. The images featured below are part of that collection and have been selected as representing some of the pioneers of the Nineteenth Century.

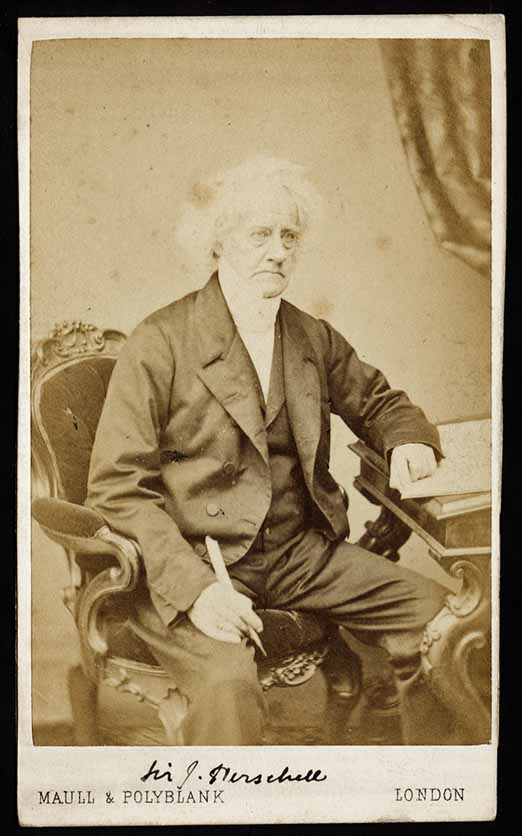

Sir John Herschel (1792-1871)

Herschel began his career as a distinguished mathematician who also worked in the fields of chemistry, botany and, like his father Sir William Herschel, he applied himself in the field of astronomy. In 1834, surveying the sky from the Cape of Good Hope, he mapped and catalogued the southern skies, discovered thousands of new celestial objects, discovered 525 nebulae and clusters and named seven of Saturn’s satellites (Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan and Iapetus) and four moons of Uranus (Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon).

Furthermore, he wrote many papers on such subjects as meteorology and physical geography. However, he actually made a large impact in the field of photography: one of the original researchers of celestial photography not only did he make significant improvements to photographic processes, discovering the cyanotype (blueprint) process in 1842, but he went on to research photo-active chemicals and the wave theory of light. He coined the term photography and was the first to apply negative and positive to it.

His son, Alexander, would become Professor of Physics at Armstrong College (now Newcastle University) in 1871 where he continued pioneering work in meteor spectroscopy.

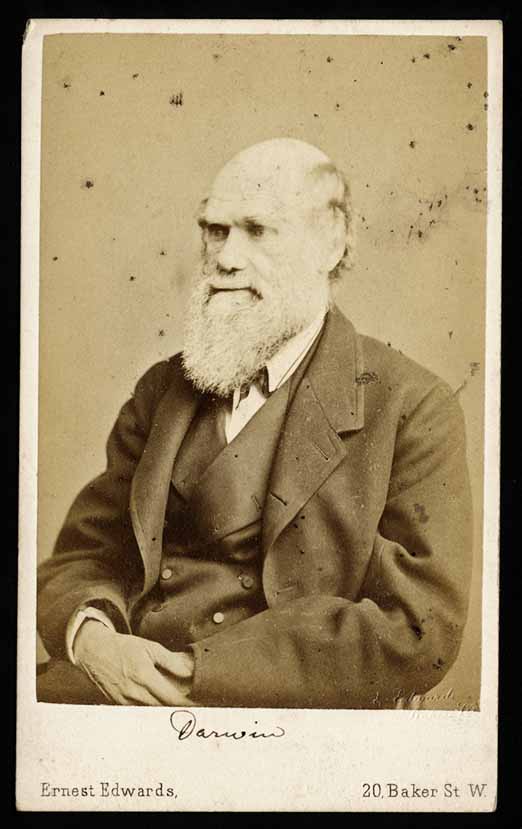

Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Darwin’s is, even today, a household name – made famous by his theory of evolution which completely revolutionised our approach to the natural world. Against the tide of belief in the biblical description of a world created by God, Darwin turned instead to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830) which argued that the Earth’s geological history and the progressive development of life could be explained as gradual changes and that fossils were evidence that animals had lived millions of years ago.

Darwin’s scientific expedition on board the HMS Beagle (1831-35) impressed upon him the rich variety of animal life and geological features and he spent the next twenty years solving the question of how animals evolve. In 1859 he published his ground-breaking On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, a first edition of which is held in the Pybus Collection. The Church, seeing the prevailing orthodoxy threatened, attacked Darwin and the idea that homo sapiens could have evolved from apes caused a backlash with satirists of the day lampooning Darwin in simian caricatures.

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930)

Nansen was a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate whose devotion to humanitarian causes such as refugees, prisoners of war and famine victims had saved many lives after World War I. First and foremost he was a scientist and explorer. In 1888 he crossed the Greenland icecap by ski and man-hauled sledge during which expedition he and his team of six collected scientific and meteorological data.

However, he became one of the pioneers of oceanography after sailing from Christiania (Oslo) to the New Siberian Islands on board the Fram in 1893. The boat froze into the ice and drifted until it was able to sail south in August 1897, following a strong east-west current that Nansen had argued must flow from Siberia towards the North Pole and Greenland. Although Nansen had not stayed with the boat, having instead made an unsuccessful bid for the Pole, his team collected information about currents, winds and temperatures and proved that there was no land near the Pole on the Eurasian side, but an ice-covered ocean. From this point, Nansen focused his research on oceanography, specifically compiling data from the Norwegian Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

The Spence Watson/Weiss Archive contains several letters from Nansen to Robert Spence Watson, and the extract given below complements the photograph of him on skis.

“… now I am again back in my dear country and am happy, one of the first days my wife and I will take to our ‘ski’ and go up in the mountains to live their [sic] for some time I must get some pure Norwegian mountain-air into my lungs again. It is a charming life to be in the mountains in the winter to feel oneself like a bird as one rushes over the snowfields undisturbed by human foot and then when the night comes to sleep in the snow with the sky as a tent. Oh you are so free, we both enjoy it immensely.”

Letter to Robert Spence Watson: Lysaker, 7 March 1892 (SW/1/13/3)

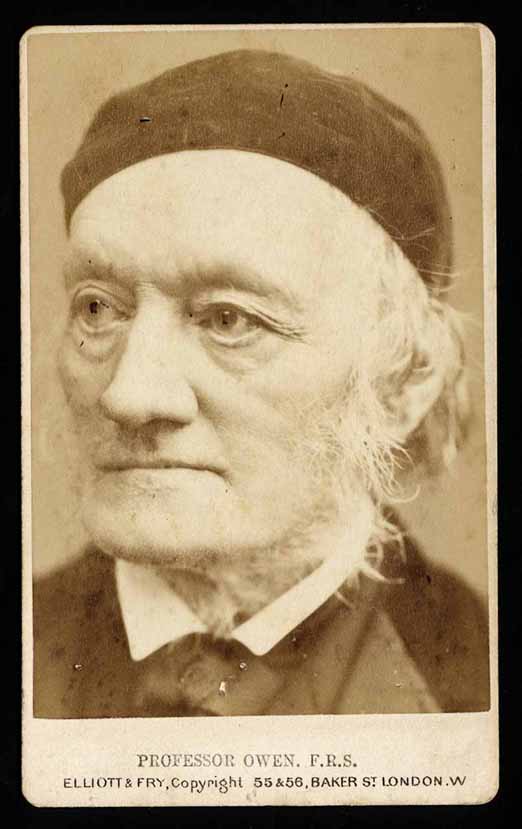

Professor Richard Owen (1804-1892)

Owen, an anatomist and palaeontologist, had a long and distinguished career in museums and created a name for himself as a controversial but brilliant scientist. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, designed the life-sized dinosaur exhibits for the Great Exhibition (1851) and his Hunterian Lectures were well-attended but his successful campaign for a dedicated natural history museum, thereby founding the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, was one of his greatest achievements.

Furthermore, although Owen rejected Darwin’s theory of evolution, being convinced of the immutability of species, he nevertheless published notable works on fossils and it was he who, building on the work of others, first classified dinosaurs and coined the term. (Owen came to revise his ideas on transmutation but maintained his belief in a divinely-created species model.)

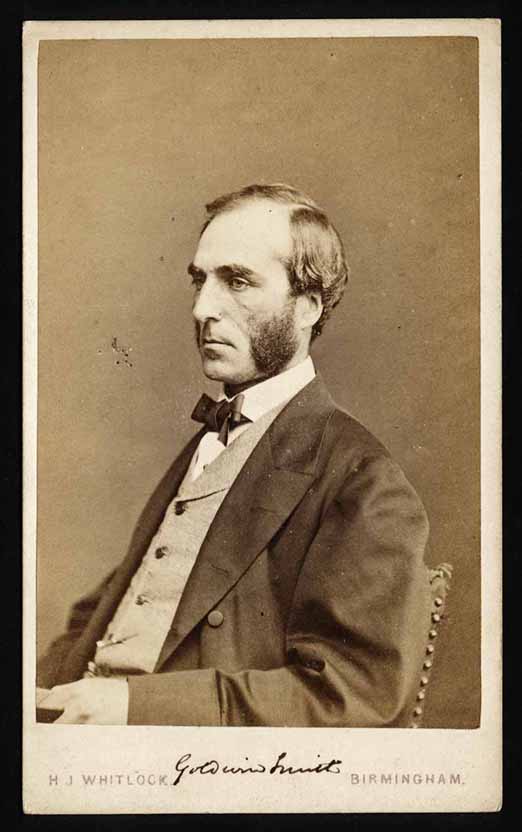

Goldwin Smith (1823-1910)

Smith’s roles were many and varied: historian, journalist, poet and translator to list a few. He was well-known as a writer on religious and political issues and was an early advocate of colonial emancipation, House of Lords reform and the separation of Church and State.

However, it is his work as a university reformer which stands out. Smith had demanded a Royal Commission of inquiry into the administration of Oxford University and its report (1852) suggested that religious tests should be relaxed, and that a teaching professoriate should be created. He also sat on the Popular Education Commission of 1858, chaired by the Duke of Newcastle. In his pamphlet, The Reorganization of the University of Oxford (1868), his recommendations included the abolition of celibacy as a condition of the tenure of fellowships and that the individual colleges merge for lecturing.

That same year, he left England for the professorship of English and Constitutional History at Cornell University – the institution to which he would later gift his private library and a $14, 000 endowment. He moved to Toronto in 1871 (where he lived out his remaining years). Here he sat on the Council of Public Instruction and wrote about the place and function of universities in Canada.

Throughout his life he argued that men of all classes should be afforded the opportunity of university education, that universities should be free from political domination and called for the raising of standards and the establishment of provincial universities.