Frederick Douglass’ story as a black American started in the same way as many others of his era, born into slavery. Thanks to his determination and good luck he was able to escape the lifelong toil that many of his fellow black Americans endured, educate himself and then tell his story highlighting the plight of fighting for the rights of black Americans. The story of his life includes a journey to the UK, and Newcastle, where he would meet a local family that had a lasting impact on his ability to live a free life in America.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in 1818 on a plantation in Talbot, Maryland. His father was white, and possibly the ‘owner’ of his mother. He was removed from his mother as a young child, and only had limited contact with her prior to her death, while Douglass was still a child. After being a slave for a number of years he escaped from his owner in Baltimore on the 3rd of September 1838 and travelled to New York. Once there he set about educating himself and eventually telling his story through an autobiography.

In 1845 ‘The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave: written by himself’ was published. This detailed his early life, escape from slavery, and new life as a free man. Across the Atlantic and during the early years of Douglass’ life, the Whig government in Britain (led by Earl Grey II who hailed from Northumberland) passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This act would make owning a slave in much of the British Empire illegal by 1840.

In August 1845 Frederick Douglass sailed across the Atlantic to Great Britain to promote his cause. A review of his book was published in July 1846 in the Newcastle Guardian. The review highlights in critical terms, the American ‘institution of slavery’ and introduces his story and selected quotes from his work.

During his 19 month stay in Britain he toured the country giving public lectures detailing his life, slavery in America and promoting abolition. This included a short stay in Newcastle, at the home of Henry and Anna Richardson and their sister-in-law Ellen. They were Quakers who lived in a house on Summerhill Grove near the city centre. His stay, and the impact the family had on Douglass’ life is commemorated by a plaque on the house. He made such an impact on the Richardson’s that they set about raising £150 and instructed a lawyer in America to formerly buy Douglass’ freedom from his former enslaver in late 1846.

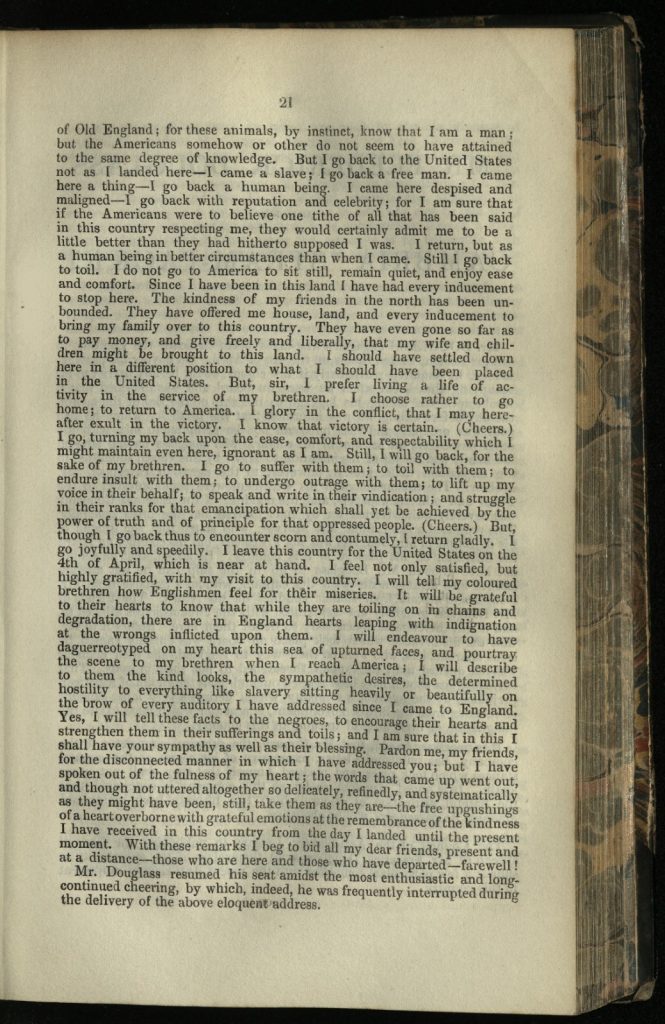

Near the end of his tour of Britain Douglass was invited to give a farewell speech at the London Tavern on the 30th of March 1847 by the Council of the Anti-Slavery League. They later published a transcript of the speech he gave, a copy of which forms part of Special Collection’s Cowen Tracts Collection, collected by Joseph Cowen, a 19th Century reformist MP from Newcastle. You can read more about the life of Joseph Cowen here.

In his speech at the London Tavern Frederick Douglass covers a number of topics. He covers the American constitution, the slave keeping system and references the abolition of slavery in Canada which had been enacted by Earl Grey’s government.

He went on to talk about the purchase of his freedom by the Richardson’s saying:

… As to the kind friends who have made the purchase of my freedom, I am deeply grateful to them. I would never have solicited them to have done so, or have asked them for money for such a purpose. I never could have suggested to them the propriety of such an act. It was done from the prompting or suggestion of their own hearts, entirely independent of myself…. (Cowen Tracts, Vol.17, No.12, pg16)

Later in his speech he went on to recount his feelings and experience of the 19 months he spent in Britain, contrasting it with the conditions he encountered in Boston before he boarded the Cambria and travelled across the Atlantic:

… I say that I have here, within the last nineteen months, for the first time in my life, known what it was to enjoy liberty. I remember, just before leaving Boston for this country, that I was even refused permission to ride in an omnibus. Yes, on account of the colour of my skin, I was kicked from a public conveyance just a few days before I left the “cradle of liberty”. (Cowen Tracts, Vol.17, No.12, pg19)

He also recounts his experience of being refused entry to churches in Boston and not being permitted to “even to go into a menagerie or theatre, if I wished to have gone there” (Pg 19) and that “I was not granted any of these common and ordinary privileges of free men.” (pg 20).

He concluded his speech by explaining his hopes and plans for his return to America saying:

…I go, turning my back upon the ease, comfort, and respectability which I might maintain even here, ignorant as I am. Still, I will go back, for the sake of my brethren. I go to suffer with them; to toil with them; to endure insult with them; to undergo outrage with them; to lift up my voice in their behalf; to speak and write in their vindication; and struggle in their ranks for that emancipation which shall yet be achieved by the power of truth and of principle for the oppressed people… (Cowen Tracts, Vol.17, No.12, pg21)

The speech he gave at the London Tavern gives us a valuable insight in Frederick Douglass’ own words of his experiences of slavery, how he valued the time he spent in Britain and the people that met and supported him while here. It also demonstrates that though he was now free himself he saw his future in helping his enslaved brethren, using his platform to promote their cause and work towards their emancipation, even if that meant experiencing the racial prejudices of 19th Century America.

On the 4th of April Frederick Douglass embarked the Cambria to travel across the Atlantic back to the United States. On boarding he was informed that the birth he had booked was occupied and that he would not be allowed to mix with the other passengers on account of his colour. After returning to America he would go on to spend the next 50 years working and campaigning for the rights of black Americans and women. He died in Washington DC, aged 77 in February 1895. Newcastle University’s Frederick Douglass Building, close to where he stayed during his time in Newcastle, is named in his honour.