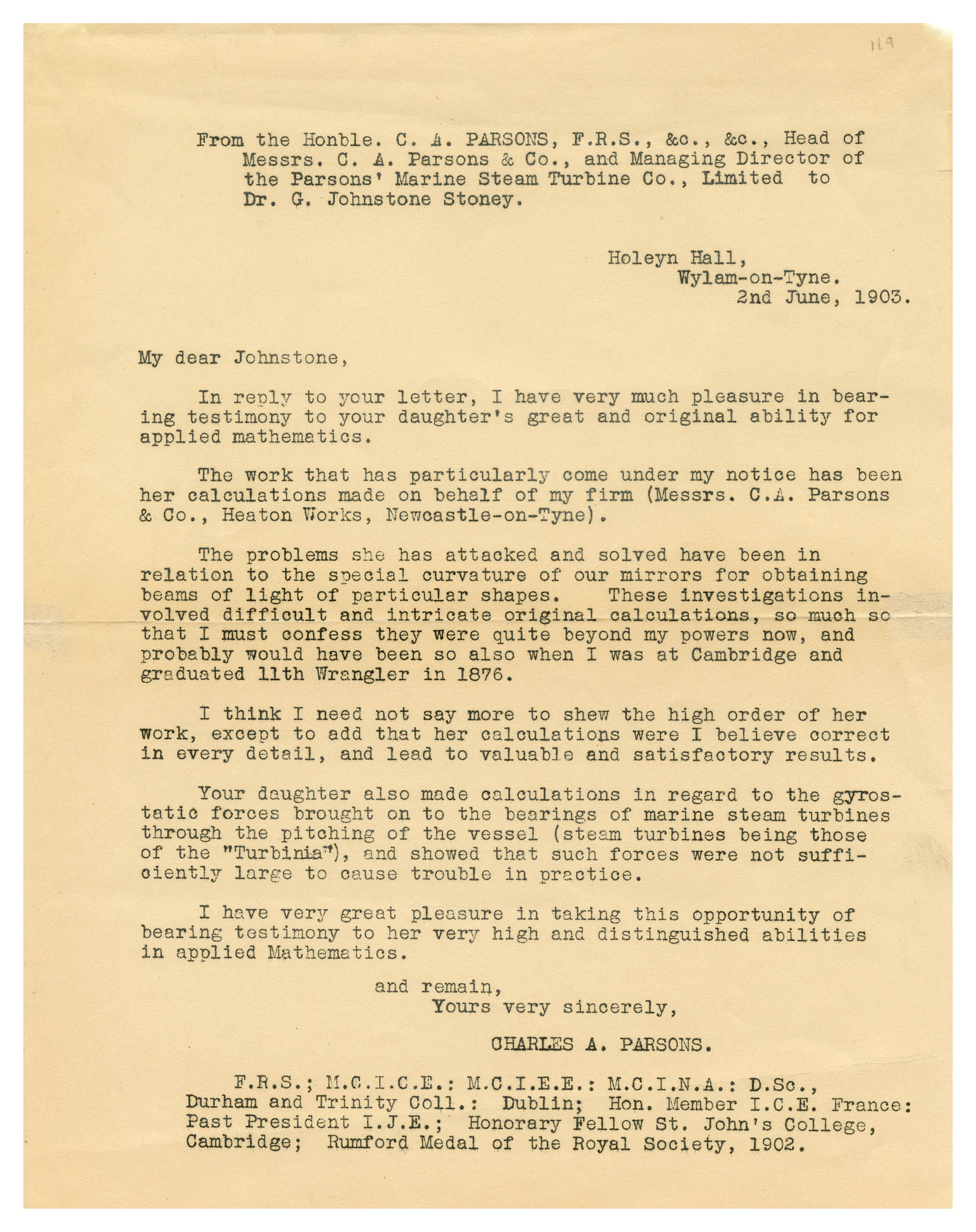

Letter from Charles Algernon Parsons to George Johnstone Stoney concerning mathematical work undertaken by on the the Stoney’s daughters (GB186/MSA/2/22)

Thank you to the Heaton History Group, whose research into the Stoney family of Heaton solved one of the mysteries in our archive! A fascinating letter in our Manuscript Album (Letter from Charles Algernon Parsons to George Johnstone Stoney concerning mathematical work undertaken by one of Stoney’s daughters’, GB186/MSA/2/22) was obviously about one of the Stoney sisters, but we didn’t know which one. Whilst we still can’t be 100% sure, the Heaton History Group have found evidence that one sister, Edith, worked for the Parsons firm whilst living in Heaton in Newcastle, and all evidence points to Edith as our mystery mathematical genius!

You can read the first installment in March 2016’s Treasure of the Month, ‘The Turbinia Steamship and a mystery in the archives…‘

The following is an extract from the Heaton History Group’s research piece. A full version, which includes their research about all of the Stoney family, including Edith’s brother George who was also connected to the Turbina story, can be seen here.

The Turbinia

Most people in Newcastle have heard of Sir Charles Parsons, the eminent engineer whose invention of a multi-stage steam turbine revolutionised marine propulsion and electrical power generation, making him world famous in his lifetime and greatly respected still. Parsons’ Heaton factory was a huge local employer for many decades. It survives today as part of the global firm, Siemens.

But, of course, Charles Parsons did not make his huge strides in engineering alone. He was ably supported by a highly skilled workforce, including brilliant engineers and mathematicians, some of whom were much better known in their life times than they are today.

One that certainly deserves to be remembered is Edith Anne Stoney. Edith worked for Parsons only briefly but her contribution was crucial. This is her story.

Family background

Dr George Johnstone Stoney (1826-1911), Edith’s father, was a prominent Irish physicist, who was born near Birr in County Offaly. He worked as an astronomy assistant to Charles Parsons’ father, William, at nearby Birr Castle and he later taught Charles Parsons at Trinity College, Dublin. Stoney is best known for introducing the term ‘electron’ as the fundamental unit quantity of electricity. He and his wife, Margaret Sophia, had five children whom they home educated. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Stoney children went on to have illustrious careers. Robert Bindon became a doctor in Australia; Gertrude Rose was an artist; George Gerald was an Engineer (who also worked on Turbina in his career); and Florence Ada (awarded the OBE in 1919), was the first female radiologist in the UK. But it is Edith Anne whose mathematical genius is shown in the fascinating letter we have here at Newcastle University Special Collections.

Edith Anne Stoney

Edith was born on 6 January 1869 and soon showed herself to be a talented mathematician. She won a scholarship to Newham College Cambridge where, in 1893, she achieved a first in the Part 1 Tripos examination. At that time, and for another 50 years afterwards, women were not awarded degrees at Cambridge so she did not officially graduate but she was later awarded both a BA and MA by Trinity College Dublin.

After graduation, Edith came to Newcastle to work for Charles Parsons. In a letter sent by Charles Parson to Edith’s father, George Johnstone Stoney, in 1903. Parsons pays tribute to:

your daughter’s great and original ability for applied mathematics… The problems she has attacked and solved have been in relation to the special curvature of our mirrors for obtaining beams of light of particular shapes. These investigations involved difficult and intricate original calculations, so much so that I must confess they were quite beyond my powers now and probably would have been also when I was at Cambridge… Your daughter also made calculations in regard to the gyrostatic forces brought onto the bearings of marine steam turbines…

It looks like the sort of reference someone might write for a perspective employer except that, a sign of the times, it doesn’t mention Edith by name and is addressed to her father.

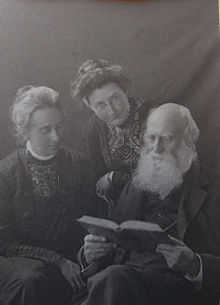

Edith, Florence and George Johnstone Stoney. Image courtesy of Heaton History Group

After working in Heaton, Edith went on to teach mathematics at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and then lecture in physics at the London School of Medicine for Women in London. There she set up a laboratory and designed the physics course.

In 1901, she and her sister, Florence, opened a new x-ray service at London’s Royal Free Hospital and she became actively involved in the women’s suffrage movement as well becoming the first treasurer of the British Federation of University Women, a post she held from 1909-1915.

During WW1, both sisters offered their service to the French Red Cross to provide a state of the art radiological service to the troops in Europe. In the x-ray facilities at a new 250 bed hospital near Troyes in France, planned and operated by her, she used stereoscopy to localise bullets and shrapnel and pioneered the use of x-rays in the diagnosis of gas gangrene, saving many lives.

She was posted to Serbia, Macedonia, Greece and France again, serving in dangerous war zones for the duration of the war. The hospitals in which she worked were repeatedly shelled and evacuated but she continued to do what she considered to be her duty. Her war service was recognised by several countries. Among her awards were the French Croix de Guerre and Serbia’s Order of St Sava, as well as British Victory Medals.

After the war, Edith returned to England, where she lectured at King’s College for Women. In her retirement, she resumed work with the British Federation for University Women and in 1936, in memory of her father and sister, she established the Johnstone and Florence Stoney Studentship, which is still administered by the British Federation of Women Graduates to support women to carry out research overseas in biological, geological, meteorological or radiological science.

Edith Anne Stoney died on 25 June 1938, aged 69. Her importance is shown by the obituaries which appeared in ‘The Times’, ‘The Lancet’ and ‘Nature’. She will be remembered for her pioneering work in medical physics, her wartime bravery and her support for women’s causes. Although her time in Newcastle was brief, she deserves also to be remembered for her contribution to the work in Heaton for which Charles Parsons is rightly lauded.

Thank you to Heaton History Group for this piece.

Link to related article: The-turbina-steamship-and-a-mystery-in-the-archives/