The below images are taken from the items in the Thomas Baker Brown archive and the Sir Lawrence Pattinson archive. To view these items and many more, please visit the exhibition on Level 1, Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University.

The exhibition is open to the public from November 2016 – February 2017.

Wars and Rumours of Wars

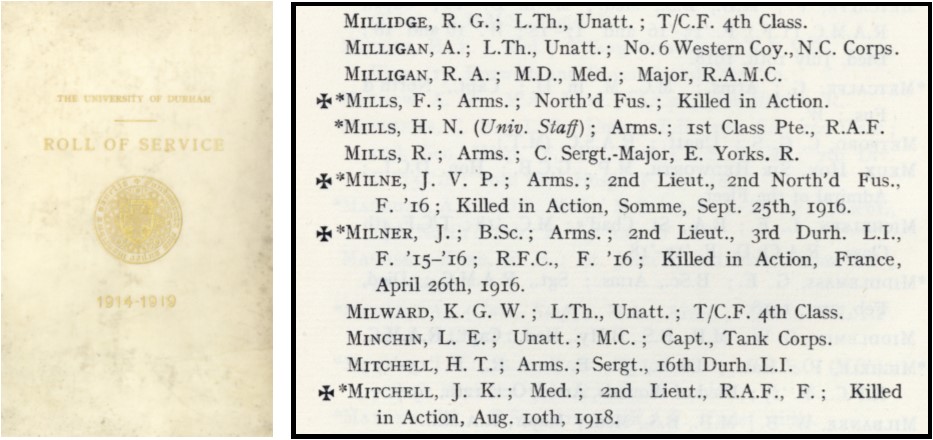

On 28th July 1914 World War I broke out. It was thought that the war would only last a few months, and the troops would be home for Christmas. A large proportion of men eagerly volunteered to join the forces in the spirit of pride and honour. Some saw it as a way out of unemployment, and others were obliged to go by their employers. Conscription, where men deemed fit and able to go to war were signed up by the nation, was not needed until 1916 when the number of volunteers dwindled.

Thomas Baker Brown and Sir Lawrence Arthur Pattinson both served during World War I and documented their experiences through their correspondence with their families back home. Material below is taken from their archives which have kindly been donated to Newcastle University Special Collections.

Thomas Baker Brown

Thomas Baker Brown was born on the 22nd December 1896 in Tynemouth and later moved to North Shields with his family, where he attended Kettlewell School, and then went on to work as a clerk.

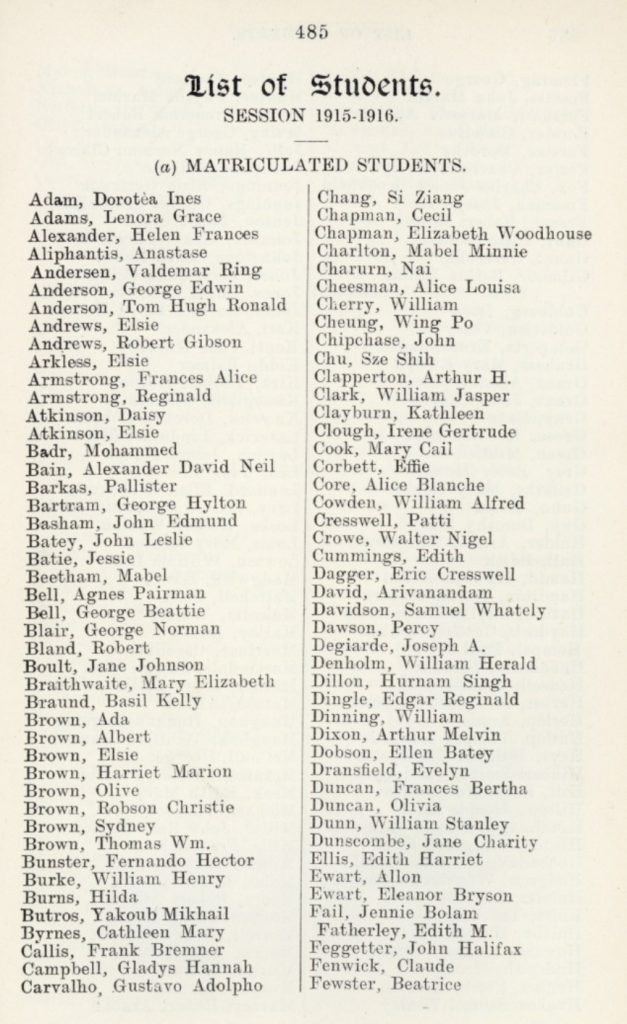

On the cusp of his 19th birthday, Brown joined the H.M. Army at the Scottish Presbyterian Church Hall in Howard Street, North Shields on Friday 26th November 1915.

Photograph of Thomas Baker Brown in uniform wearing an ‘Imperial Service Badge’

Sir Lawrence Pattinson

Sir Lawrence Pattinson, born on 8 October 1890, had military aspirations long before the outbreak of war. Both he and his brother Hugh Lee IV attended Stubbington House School (considered to be a stepping stone into the forces). Hugh Lee IV studied successfully for the Army Entrance to Sandhurst, but Sir Lawrence failed his exams for the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth. As a result, Sir Lawrence went on to study at Rugby and then Cambridge.

Photograph of Sir Lawrence Arthur Pattinson

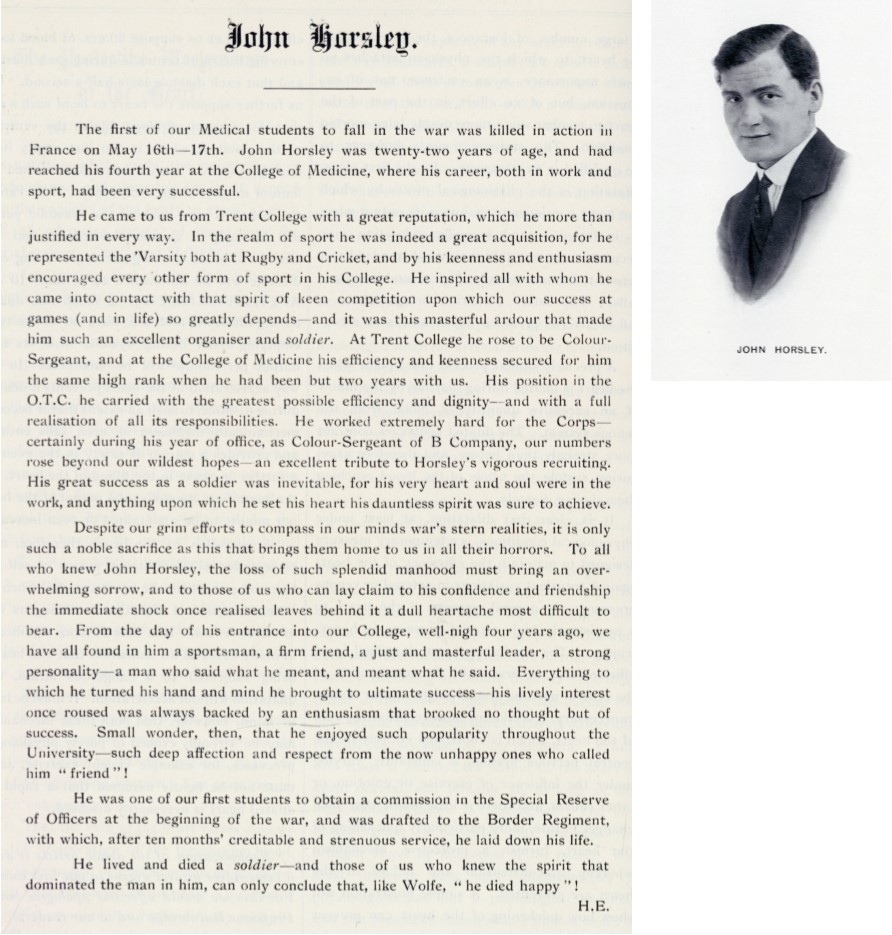

Hugh Lee IV

It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War I that Sir Lawrence was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 5th Durham Light Infantry as part of the Territorial Army. However, his brother, who was now on the front line in the Army, warned him of the dangers of becoming a soldier. On his brother’s recommendation, Sir Lawrence Pattinson enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps.

Unfortunately, shortly after warning his brother of the dangers of being a soldier, Hugh Lee IV was killed in action . He was just one of the 908,371 British fighters to die in World War I.

Pilots and Tommies

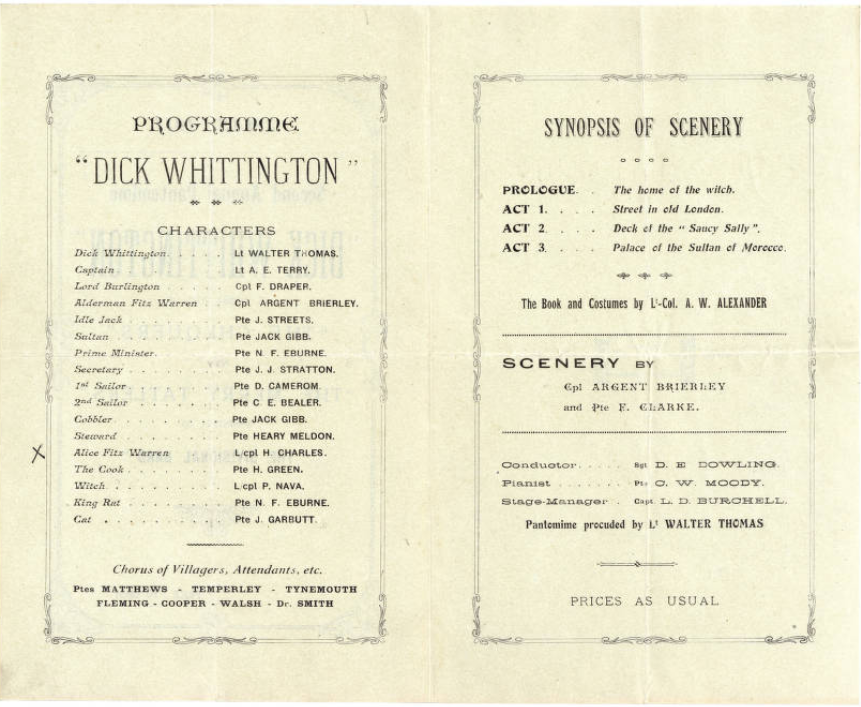

Scarcroft Schools

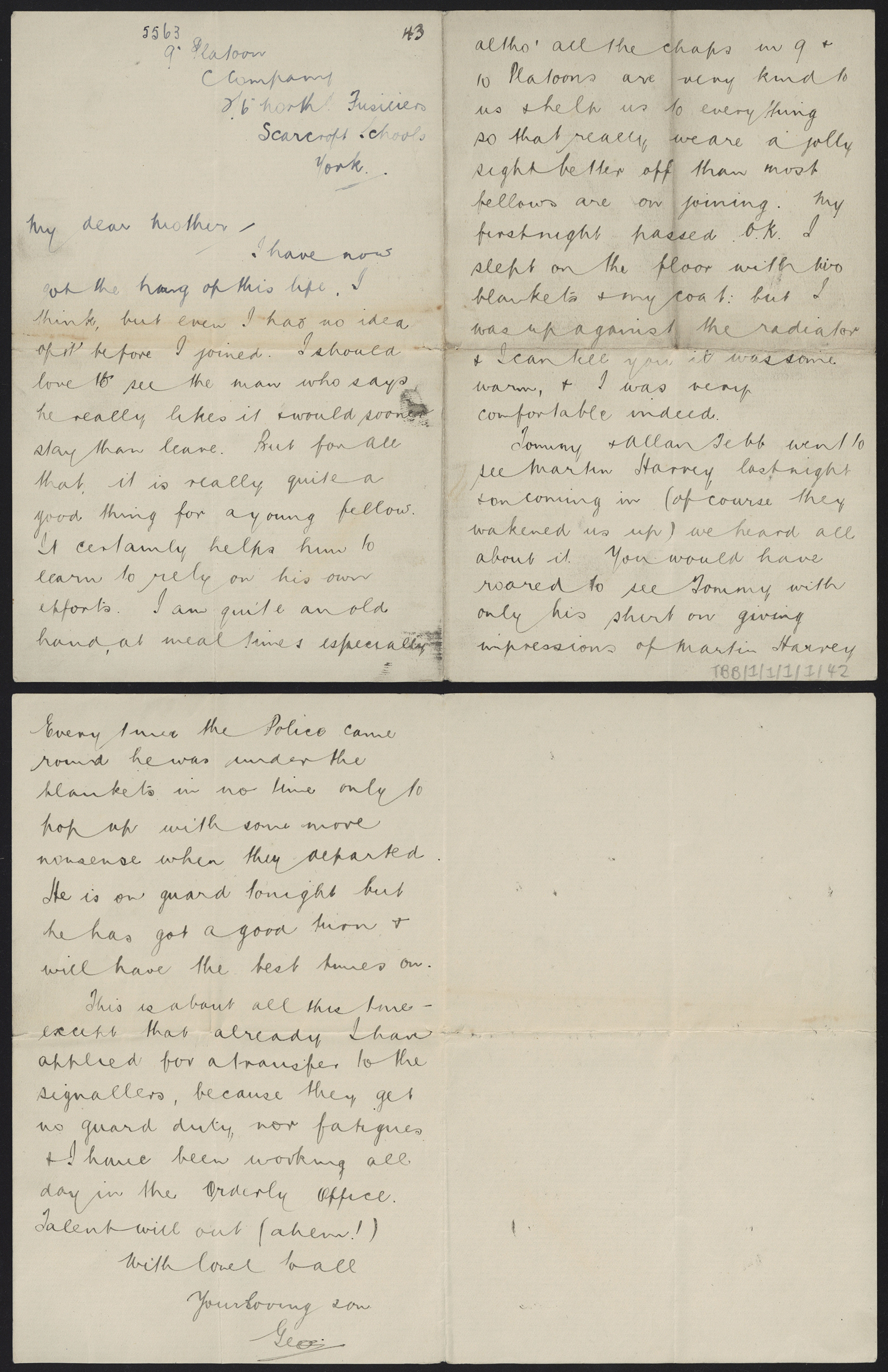

By the 5th December 1915, Thomas Baker Brown was serving in the ‘Clerks Platoon’ for the 6th Northumberland Fusiliers at a training camp at Scarcroft School, York. As a soldier, or “tommy”, training would begin with basic physical fitness, drill, march discipline and essential field craft. Tommies would later specialise in a role and Brown received training in bombing, signalling and musketry. He suffered from poor eyesight and was issued with glasses. After failing to be transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, Brown was placed into the signalling section and later drafted to France alongside his brother George, as part of the 2/6th Northumberland Fusiliers, 32nd Division.

First letter sent home from Thomas Baker Brown to his mother following joining the army. The letter describes his trip from Newcastle to a training camp in York, and being put into the ‘Clerks Platoon’. Written from 9th Platoon, ‘C’ Company, 6th Northumberland Fusiliers, Scarcroft Schools, York (TBB/1/1/1/1/1)

Aviator’s Certificates

By 20 March 1915, Lawrence Pattinson had received his Aviator’s Certificates. He graduated at the Central Flying School and awarded his Wings on 5 July 1915. By 14 October 1915, he was promoted to Flight Commander RFC Temporary Captain of the Royal Flying Corps.

Letter from Lawrence Pattinson to his mother. Pattinson relates his first experiences flying alone, admitting he was ‘desperately nervous’ but did ‘fairly well’, and that it made him appreciate flying with an experienced pilot. Written from The Kings Head hotel, Harrow on the Hill, London (LAP/1/2/1)

In Flight

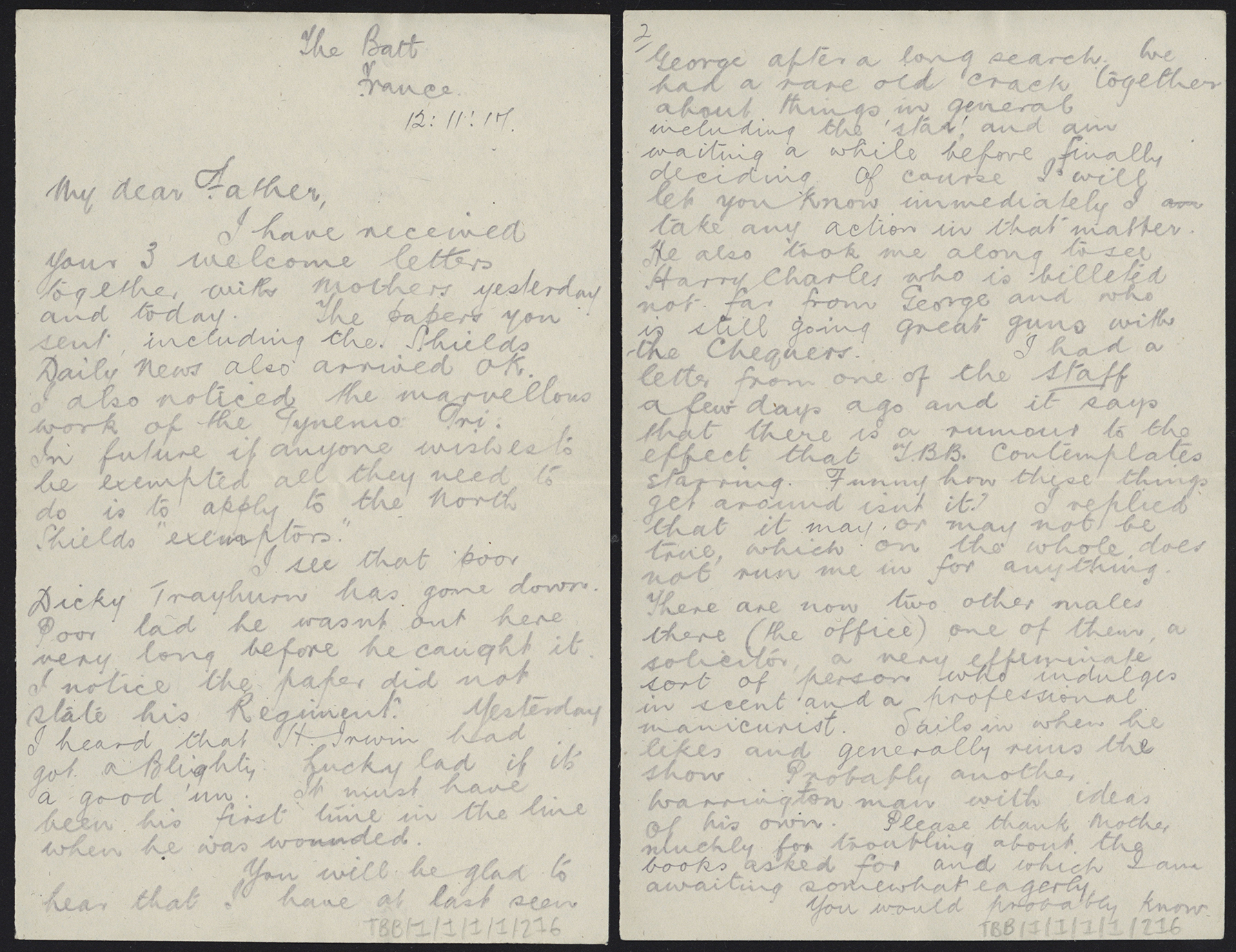

Scouts, photographic reconnaissance and bombing

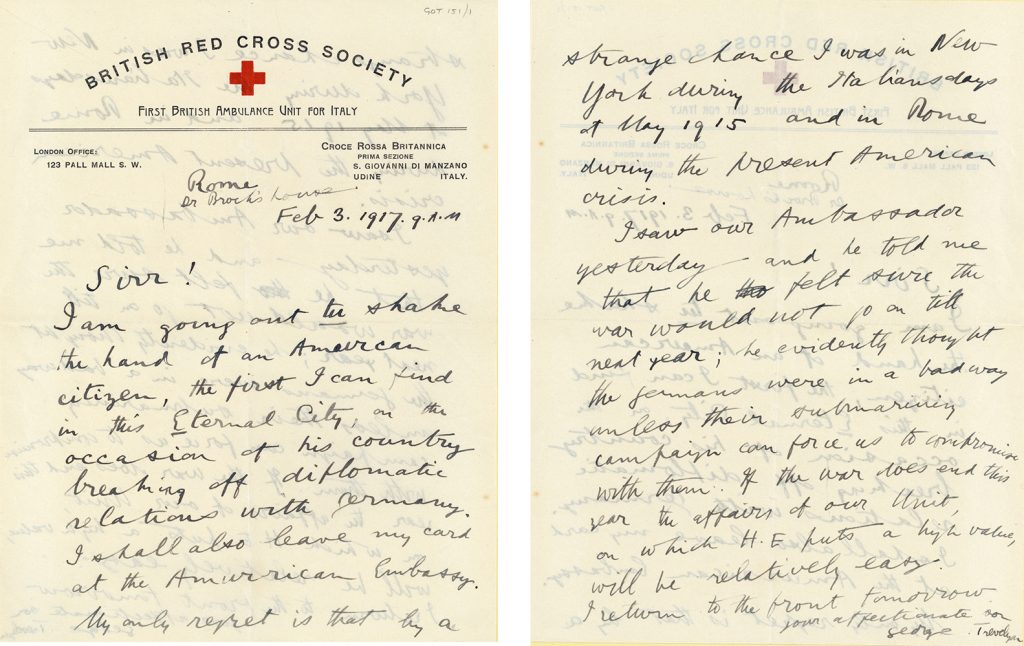

On 3 June 1915, Sir Lawrence was awarded a Military Cross for his fighting as a scout-fighter pilot, and on the 13 June 1915 he was promoted to Officer Commanding No. 57 Squadron on the Western Front. Sir Lawrence remained with the squadron for just under three years, during which time he led scouts, photographic reconnaissance and bombing.

Airplanes played a very important role in military strategy. Sir Lawrence spent a large proportion of his time on duty flying over the landscape to gather information about enemy lines. At the start of the war, this was done by sight only. As technology improved, pilots would take photographic equipment on the flights.

LAP/1/2/12/3 and LAP/1/2/12/4 – Pages 3 and 4 of a letter from Lawrence Pattinson to his mother, Mary Pattinson. He describes his morning spent doing mixed patrol and photography, during which time his propellor broke and he was confronted by German planes known as “”two tails””. He states ‘We went on taking photos and being shelled like mad’. He includes detailed drawings and annotations of the “”two tail”” planes.

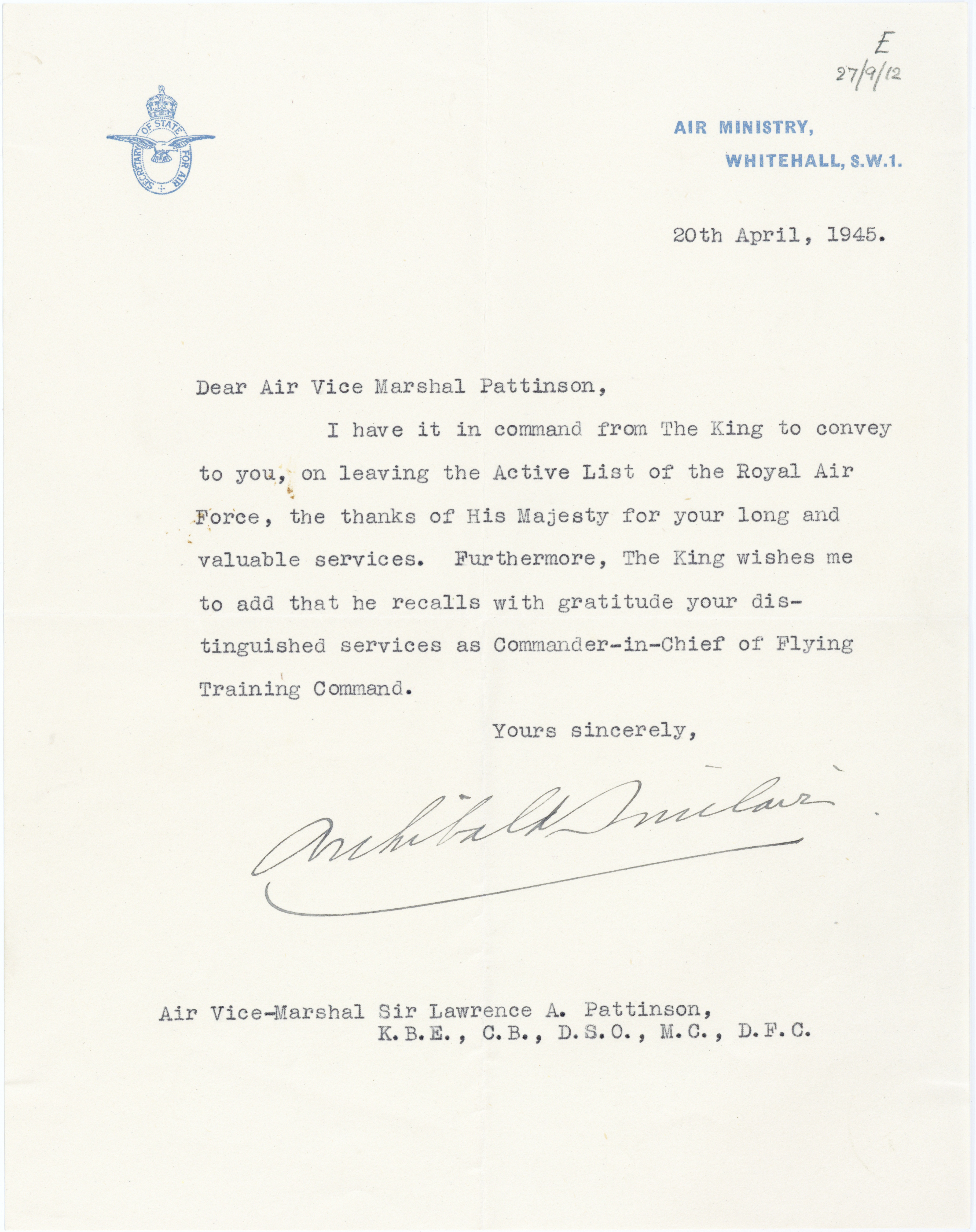

Acting Lieutenant Colonel

March 1918 saw Sir Lawrence become Officer Commanding No. 99 Squadron, and during September 1918 he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Later that year, in October, he was promoted Acting Lieutenant Colonel and command of 41st Wing, then 89 Wing in France, for the last few weeks of the war.

Captured

Military Medal

By the 1st August 1916, Brown was moved to the 21st Northumberland Fusiliers (2nd Tyneside Scottish 37th Division) and was sent on his first journey to the front line trenches. Later, in March 1917, Brown was awarded the Military Medal for his ‘heroism’ and ‘bravery’.

TBB/1/2/1 – Newspaper cutting relating to Thomas Baker Brown being awarded the Military Medal, alongside his photograph in uniform.

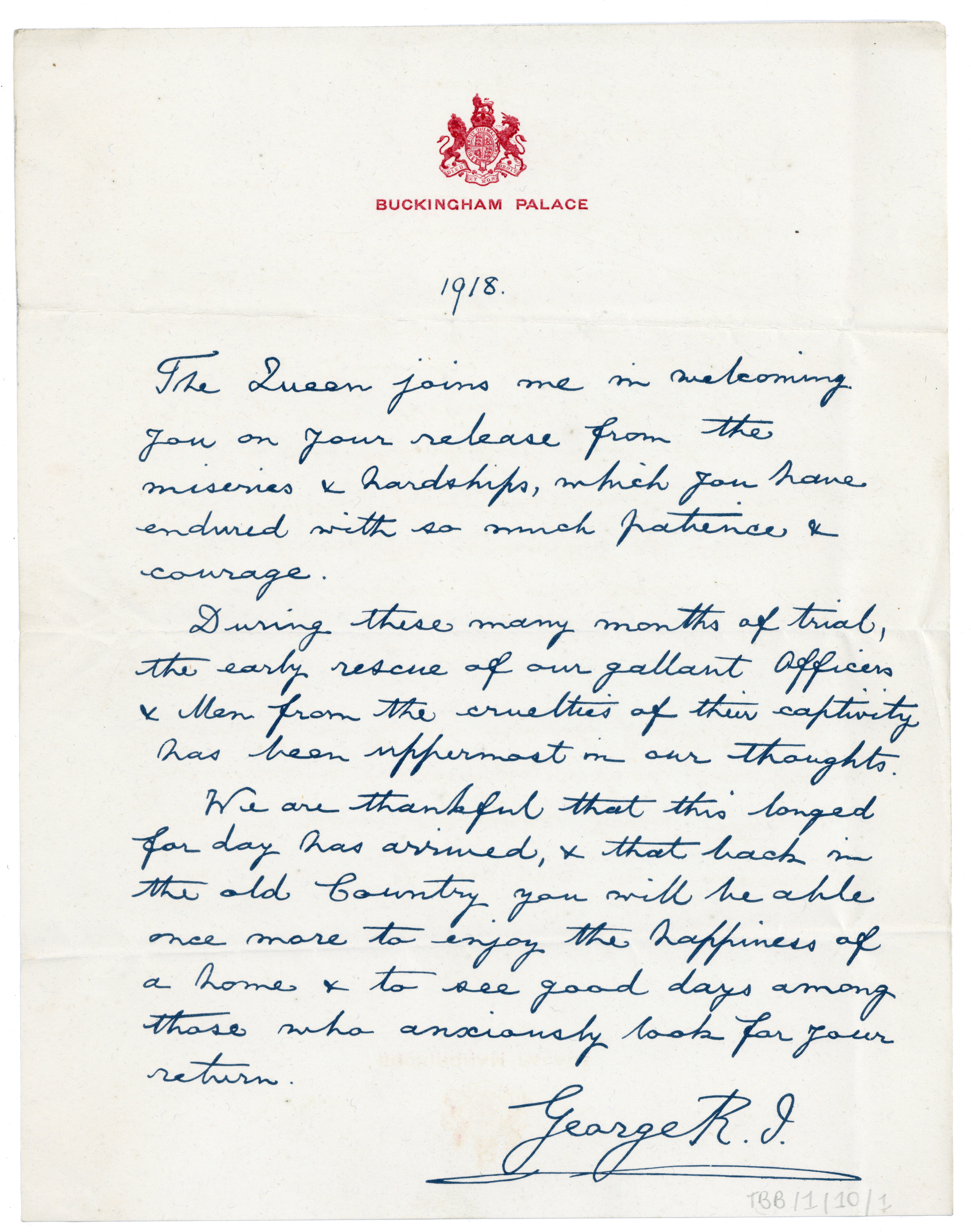

Prisoner

Brown visited the front line tranches many times over the following months, and remained uninjured, but on 21st March 1918 he was taken prisoner by German soldiers on the Arrasfront at Bullecourt. He was taken to Germany where he was placed into a prisoner of war camp in Dülmen and then transferred to Limburg by April 1918. Here, Brown worked at the Pit North Star, a coal mine in Herzogenrath.

TBB/1/1/3/2/4 – postcard from ‘Agence Internationale des Prisonniers de Guerre, British Section’. Letter states that Thomas Baker Brown has been included on a list of British prisoners despatched from Berlin on the 18/04/1918, taken prisoner unwounded, and interned at Dülmen on 21/03/1918.

a

Aftermath

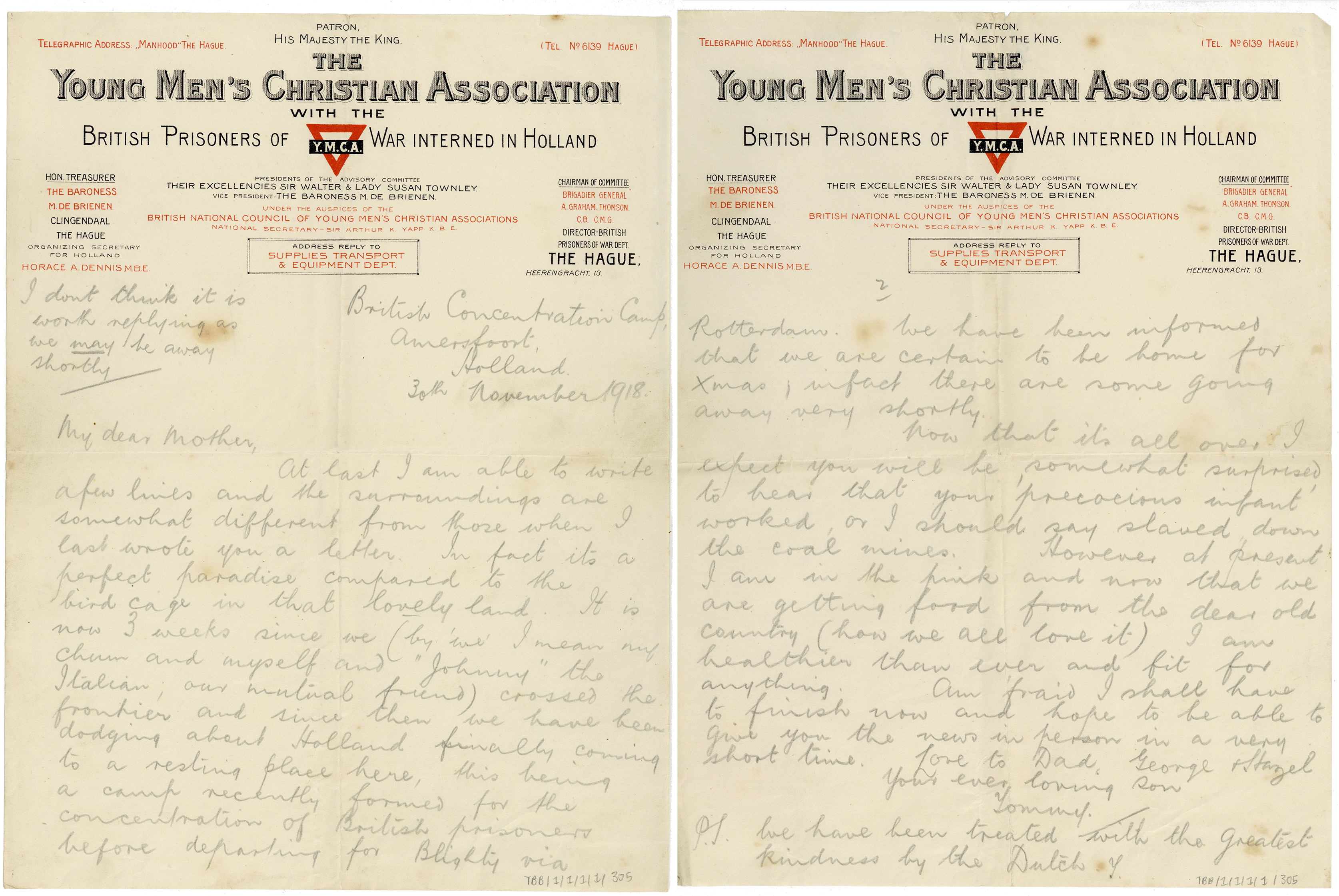

Here at last

On the 17th November 1918, on witnessing the command of the German camp breakdown, Brown and a party of five other men walked out of the gates. They made their way to Holland and boarded the S.S. Arbroath, arriving in Hull on the 8th December. Finally, he was able to take a train to a reception camp in Ripon, the last stop before his journey home.

TBB/1/10/1 – Letter from King George V to release British Prisoners of War.

Years later, in the 1930s Brown was blinded for five years, which specialists attributed it to his time in the prisoner of war camp working in poor mining conditions. He never recovered his sight and as a result was rejected to fight in World War II and served on the home front instead.

After 11 November 1918, Sir Lawrence remained in France until March 1919 to demobilize squadrons. In June 1919, Sir Lawrence was awarded his Distinguished Service Order and granted a permanent commission as Squadron Leader RAF. He was sponsored by the RAF to study at the Staff College, Camberley. Following his studies, he became Chief of Staff at RAF Cranwell where he educated officer cadets of the army. In 1933, Sir Lawrence was appointed Air Aide-de-Camp to King George V. He died on 28 March 1955.

LAP/1/4/1 – Letter from Archibald Sinclair to Sir Lawrence. Sinclair thanks Sir Lawrence, on behalf of the King, for his long and valuable service in the Royal Air Force.

Education Outreach

Thomas Baker Brown World War I Comics Anthology

Newcastle University Library’s Education Outreach Team worked with Comic Artist Terry Wiley, Lydia Wysocki from Applied Comics Etc and groups of secondary school students from four local schools to tell Thomas Baker Brown’s wartime story through the medium of comics.

Comic artist Terry Wiley created a comic telling of Thomas’ wartime story. Students from four secondary schools took part in a workshop at Newcastle University Library where they explored the Thomas Baker Brown archive. Students then learnt how to make comics using material and research gathered from the archive for inspiration.

Their comics were brought together into one anthology: The Thomas Baker Brown World War I Comics Anthology.

Click here for more information and to browse the comics online.