By Sophia Leggett

Sophia Leggett is an MLitt English Literature student at Newcastle University, specialising in Contemporary Children’s Literature. Throughout the year, she has also been working in the Special Collections department at the Robinson Library, helping to catalogue newly acquired rare books.

As she reaches the end of her time with us, we have asked Sophia to take a look at one of the hidden gems within our archive collection and tell you (and us!) a little bit more …

Taking inspiration from the three letters in the Manuscript Album collection written either to or by the great author, playwright and diarist Fanny Burney, Sophia looks a little deeper into the life and correspondence of this fascinating writer.

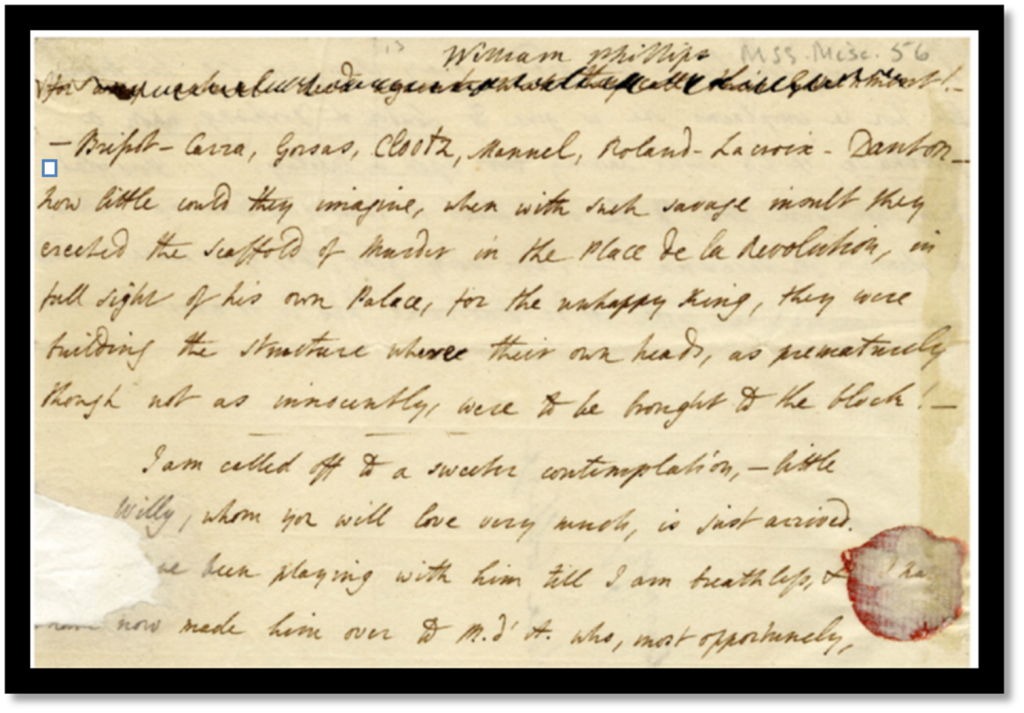

The Letters of Fanny Burney, held by Newcastle University, and available to consult in the Special Collections Reading Room, Robinson Library.

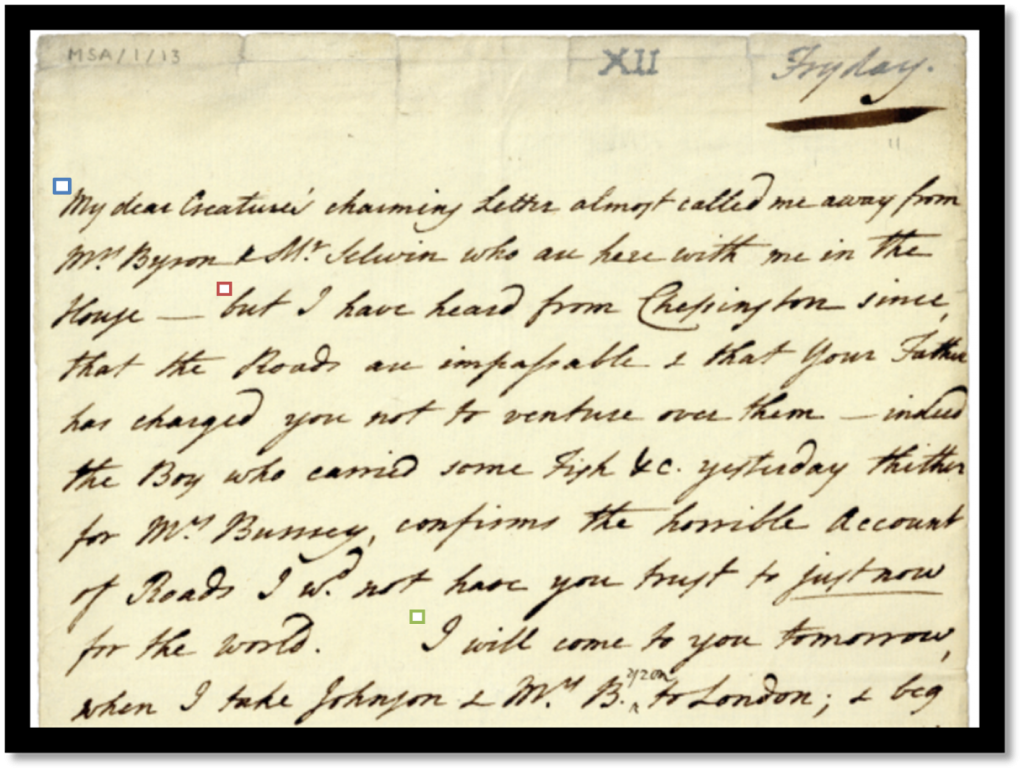

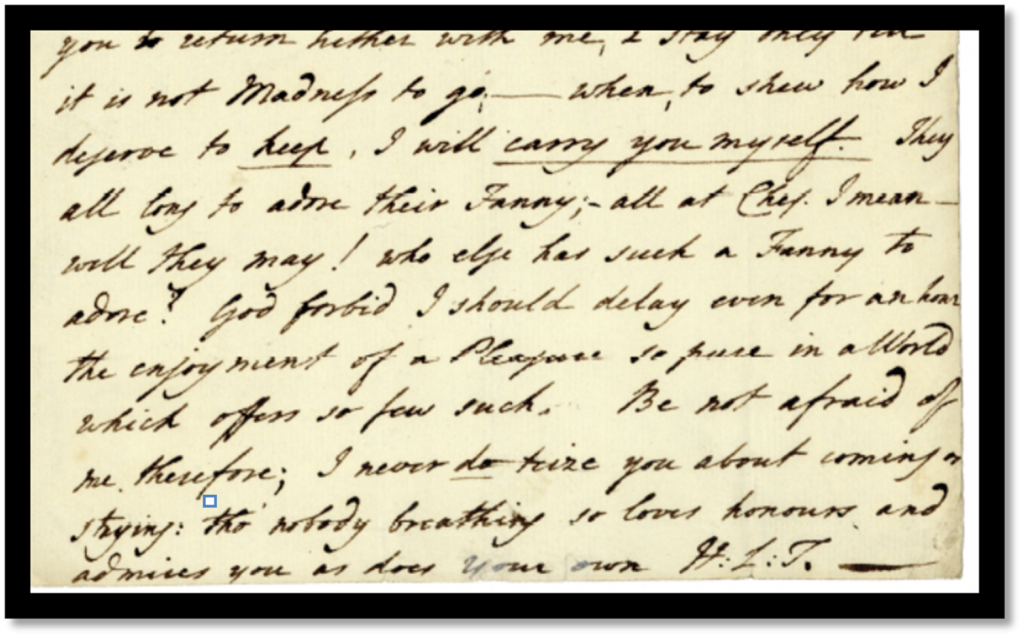

Reference ID: GB186-MSA-1-13 Letter From Hester Lynch Thrale To Fanny Burney

Reference ID: GB186-MSA-1-15 Letter From Fanny Burney To Dr Burney

Frances Burney (1752-1840) was arguably the most successful female novelist of the eighteenth century; her first novel Evelina (1778) was a publishing sensation and follow-up novels Cecilia (1782) and Camilla (1796) were considered among the best fiction of the time and were much admired by her contemporary Jane Austen. Further than this, Burney was also a keen playwright, and also wrote many letters and journals to her family and friends. Burney composed many of these letters and journals with a keen awareness of their future historical significance, giving a fascinating insight into many aspects of eighteenth century life including family, politics, court, war and pathology. Living to the incredible age of 87, Burney lived a long and fascinating life.

Family Life

Frances (‘Fanny’) Burney was born the third of six children to Charles and Esther Sleepe Burney. Her father, a musicologist, came from humble beginnings but increased his social standing through hard work and study. Her mother died when she was ten years old, and her father was remarried 5 years later to Elizabeth Allen, bringing three step-siblings into the family, and later two half-siblings. Her large family were a talented group of musicians, writers, scholars, geographers and artists. The whole family shared a habit of vividly ‘journalising’ experiences for each other, and between them left behind more than 10,000 items of correspondence. Burney’s family clearly nurtured her artistic talent, even though she did not learn to read until she was 8 and never received formal schooling. Burney was also nurtured by her father’s circle of friends, particularly as she acted as her father’s secretary as he worked on a history of music. Charles’ circle included the lexicographer Samuel Johnson, the poet Christopher Smart, the painter Joshua Reynolds, the actor David Garrick and a brewer Henry Thrale and his wife, Hester, a diarist.

Thrale Relationship

One of the letters held by Newcastle University is a letter from Hester Thrale, a friend of the family. Thrale seems to have had a very interesting relationship with the Burney family. She was allegedly strangely judgemental of them, torn between her love and admiration of the Burneys and contempt for their humble origins, referring to them as ‘a very low race of mortals’. Burney’s first novel, Evelina altered this relationship. It was initially published anonymously, but knowledge of her authorship soon broke out and Thrale saw the advantage of an acquaintance to Burney and demanded an introduction, inviting Burney to social gatherings and gaining her access to literary circles. Upon Thrale’s scandalous remarriage to musician Piozzi in 1784, Burney, in outrage, ceased correspondence with her, though they later had a partial reconciliation in 1815 in Bath.

At 35, Burney was reluctantly appointed Keeper of the Robes to Queen Charlotte at the Court of George III, after the Queen wished for a new dresser who could supply her with intelligent conversation. This was meant to be a position for life, but Burney hated it and managed to leave after five years due to ill health. Despite this, Burney left on good terms with the Royal Family, and proceeded to stay in touch. She left with a pension of £100 – half of her £200 salary. Whilst at court, Burney vividly documented Court lifestyle, providing an intriguing insight into court lifestyle as well as King George III’s ‘madness’.

France

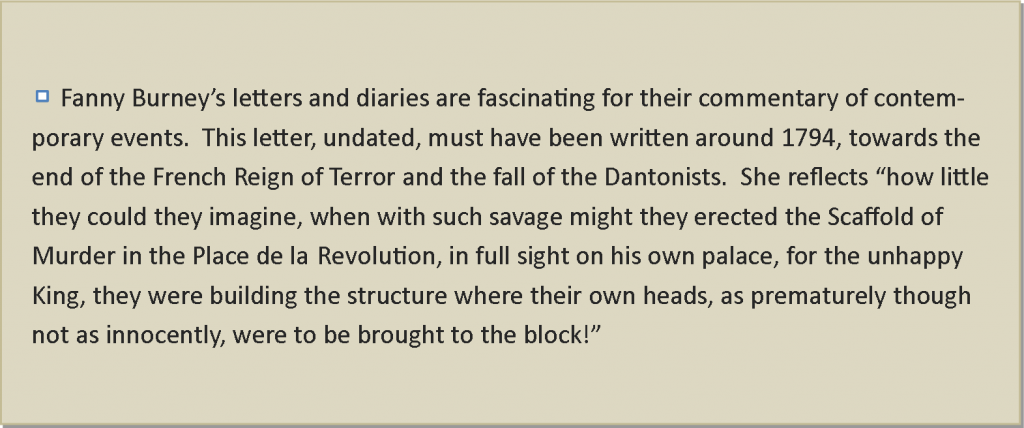

Following the French Revolution, in 1793 at the age of 41, Burney met Alexandre d’Arblay, an exiled French General, and soon after married him following a secret courtship. Due to poor relations with France following the Revolution, this was frowned upon particularly by Burney’s father, who tried to dissuade her from an imprudent match, though Burney clearly ignored him. D’Arblay was not allowed to work in England due to his nationality, and so Burney became the breadwinner of the family with her royal pension and her writing.

In 1802 Burney and her son joined D’Arblay in France, where he had returned to claim what was left of his estate and joined the French Royalist Guard. The family were then trapped in France by the breakdown of the Peace Amiens and the outbreak of war between France and England. In 1815, Burney fled from France to Belgium, and upon discovering that her husband was ill and wounded at Tréves (more than a hundred miles away from her), Burney set out to find him and take him back to England, documenting her travels through a war-torn country.

During her time in France, Burney’s journals and letters provide a fascinating insight into French society, politics and war. She also provides an intriguing pathological account of then-modern medicine. In 1811 at her home in Paris, she underwent a mastectomy for breast cancer without anaesthetic, writing a very detailed and graphic account of this operation.

The Manuscript Album is a collection of letters, purchased or given to Newcastle University Library over the last century. Although collected with no particular subject focus, each letter was chosen for its historical significance, and the album includes letters by Horatio Nelson, A.E. Houseman, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Garibaldi, and Mary Shelly to name but a few, as well as by people of local significance like Thomas Bewick, Richard Grainger, and George Stephenson. The Manuscript Album contains three letters which were written either to or by the great author, playwright and diarist Fanny Burney.