“The Boys of the OTC”

What is an OTC?

The OTC, or Officer Training Corps, was established in 1908 to ‘attract’ young men into the British army. The Corps also laid the foundation for these young men to become fully commissioned officers, which the Army sorely needed. The OTCs operated throughout the war and were vital in providing officer candidates for selection. In fact, these training corps became so critical that in 1916 new military instruction was implemented which stated that temporary commissions could only be granted if a man had been through an Officer Cadet unit.

But how did the Corps come to be?

A committee under the chairmanship of Sir Edward Ward, then permanent under secretary of state for war, was tasked with reviewing the issue of low officer recruitment numbers. He and the committee then presented a report to the British government with the following proposals:

(a) To create a system of military instruction for prospective officers, existing School 11 and University Corps should be reorganized into an “Officers Training Corps.”

(b) A selected staff should be created in the department of the War Office to supervise the organization, instruction, and examination for certificates of the Officers Training Corps.

According to Edward M. Spiers, author of COMEC OCCASIONAL PAPER. No 4: ‘The corps was to be divided into a Junior Division for public schools and a Senior Division for universities.’ These programmes trained cadets to for Certificate A and B examinations; however, only university cadets could take the latter. The examinations were divided into written and theoretical parts. Exam B was much more rigorous, with compulsory papers in elementary tactics, military law and administration as well as practical and written papers in special-to-arms training. There was also an optional paper in military history and strategy. The requirements to take Certificate B were also much more rigorous. Cadets could only take the examination if they had proved their efficiency over a two year period with mandatory attendance of special events and training camps. Possession of a Certificate B was the rough equivalent of 6 months’ residence at the Royal Military College in Sandhurst.

Was the OTC successful?

Initially, no. While thousands of University students participated, relatively few went on to earn their Certificate B status. Even fewer went on to become fully commissioned officers in the British Army.

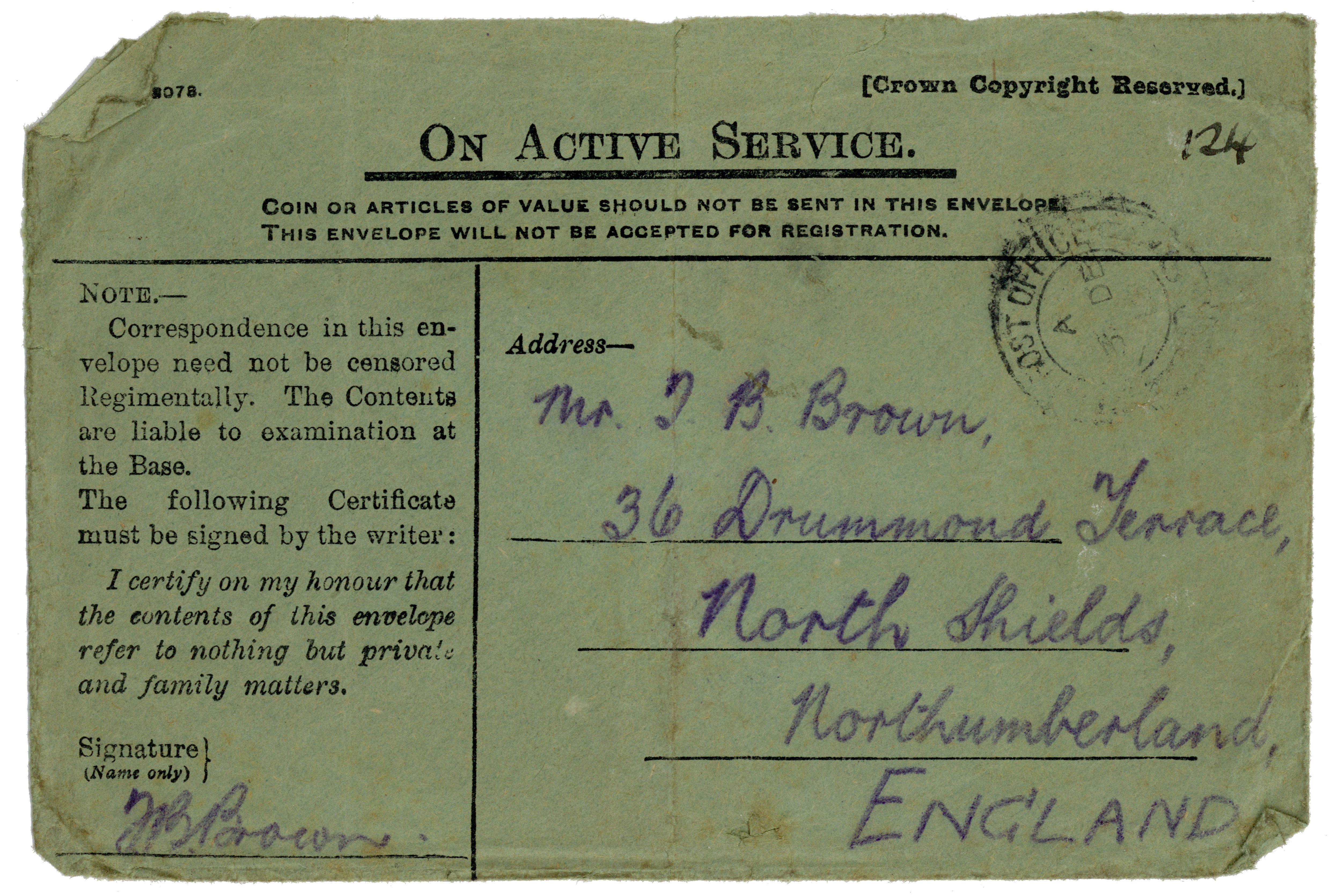

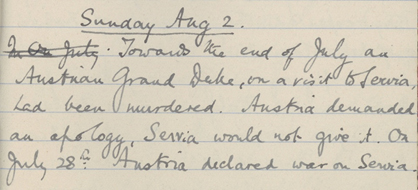

It wasn’t until 1914 that the OTC had a measurable impact. An appeal from the British government, (published on 10 August), urgently requested for 2,000 young men to come forward and take temporary commissions in the regular army. This appeal was directed specifically towards men who were, or had been, cadets in the ‘University Training Corps’. In 1914, the university students knew what was expected of them patriotically and allegedly volunteered in such numbers that the Army struggled to find them all commissions.

Spiers claimed that ‘the military contribution of the Universities’ OTCs can be assessed as 2,298 officers gazetted as officers, including regular officers, before the outbreak of war; 9,402 commissioned from August 1914 to February 1915; and another 3,278 serving in the ranks during this period.’

University Archives – Newcastle Gazette – Vol. XV, February 1915, no. 2

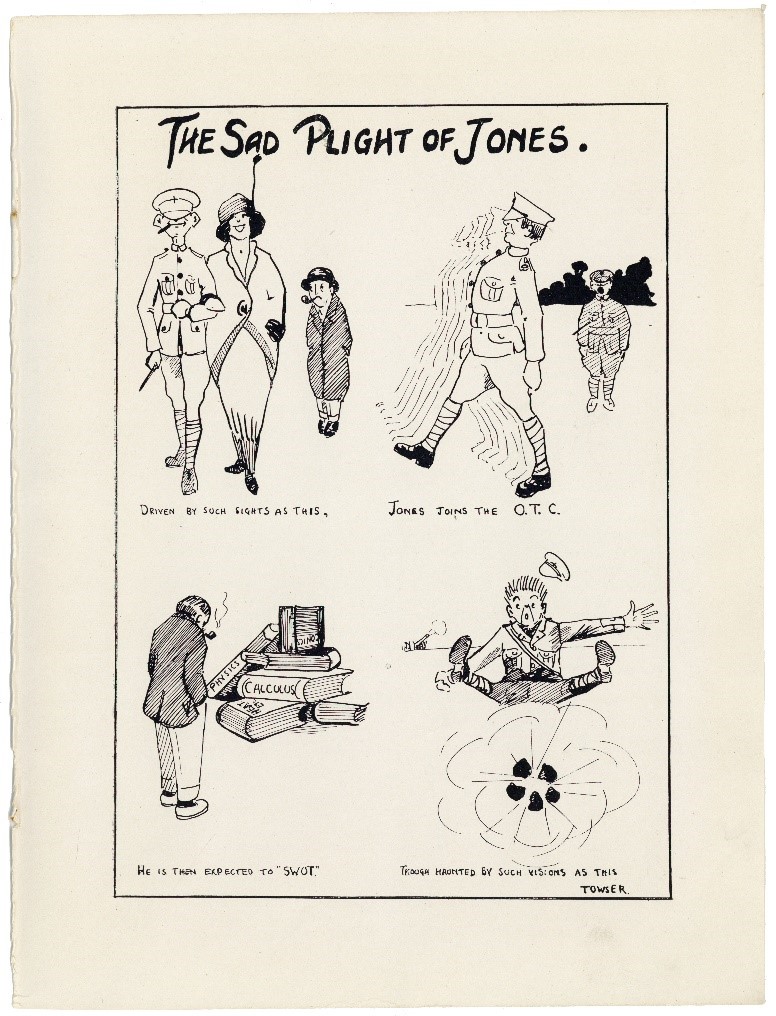

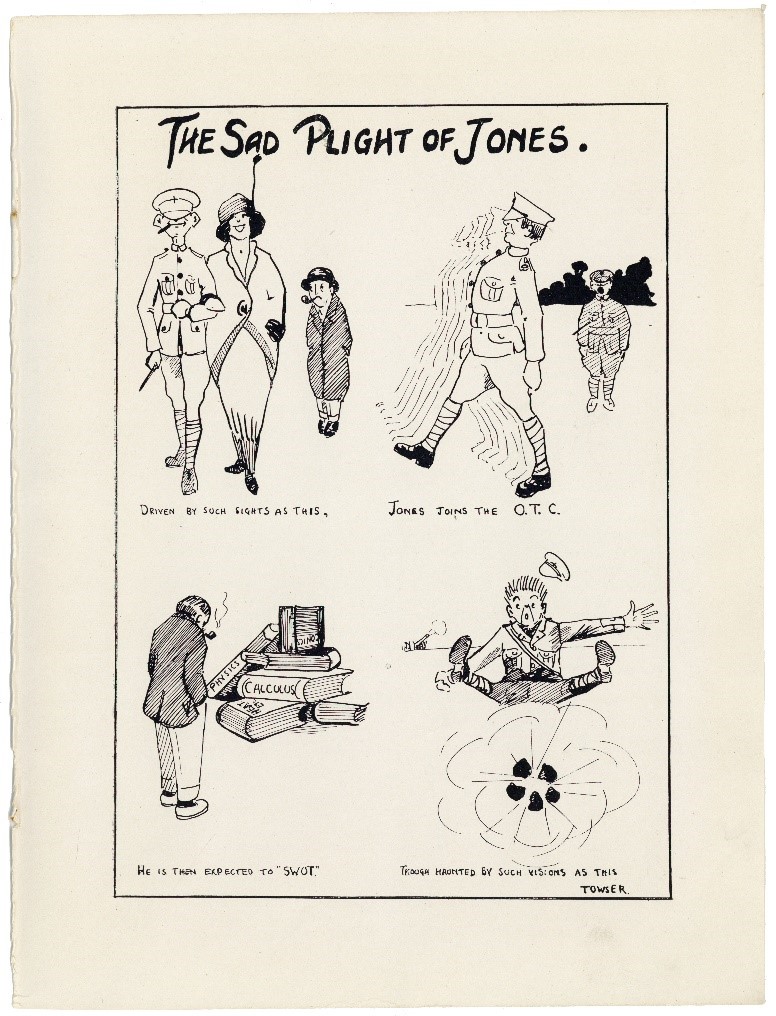

The Sad Plight of Jones caught my eye while I was scanning archived copies of Newcastle University’s magazines for the WWI archival project. While humorous, it seemed to me that the cartoon could be interpreted in a rather dark manner given the date of this particular issue.

A far cry from the boyish, carefree attitude of the OTC’s beginnings, the OTC of 1915 would have likely been suffused with feelings of the impending realities of service on the front lines. The cartoon takes the reader on a quick journey through Jones and his ‘plight’: a young man sees a beautiful woman on the arm of a uniformed soldier and thus joins the OTC. As a cadet, he is expected to ‘swot’ or study hard for his examinations, but is ‘haunted’ by visions of being shelled.

If we assume the shelling is freak mishap of a summer training camp scenario gone wrong, the cartoon is rather funny indeed. But if instead it is a reference to Cadet Jones being distracted from pretty young women and his studies by visions of being shelled on the front lines of a world war… the cartoon becomes quite bleak. As a student at Newcastle University myself, I can’t help but consider my own worries in a different perspective if the latter theory is true.

How disconnected and separate must these cadets have felt from their other university peers? It certainly leads one to wonder at the degree of patriotic duty these young men must have felt to have still continued with their cadet training despite these misgivings. I feel it is important to stress that the OTC in 1915 was not contractual. Once these cadets joined, there was no legal obligation to continue… yet thousands did.

Jessica Thomas is a student at Newcastle University and a volunteer on the ‘Universities at War’ project within the Newcastle University Robinson Library Archives.