Since play streets started in North Tyneside in 2015, with a Play England-funded pilot run by House of Object, and since we established PlayMeetStreet North Tyneside in 2017, a total of 96 streets across the borough have played out. Some of these have played out just once or twice, but most have organised a series of play streets, and around 40 play out monthly; two have been running monthly play streets since 2015.

Before two new streets started, we estimated that 94 play streets equates to approximately 1410 children and 940 adults having access to this opportunity to play and meet,[1] and that 40 regular play streets equates to approximately 600 children participating in a total of 120 hours of free, outdoor play in North Tyneside each month. In total, we estimate we’ve enabled about 180,000 child-play-hours since 2017.

These numbers suggest that North Tyneside’s play streets scheme is one of the largest in the country, with only Bristol (where the scheme started) and London supporting a larger number of play streets. North Tyneside’s scheme is approximately the same size as that of Leeds, a city with a population considerably bigger than North Tyneside (and where the play streets scheme is managed and developed by the local authority). We’ve attracted considerable local and regional media attention, including, for example, this short piece by ITV Tyne Tees.

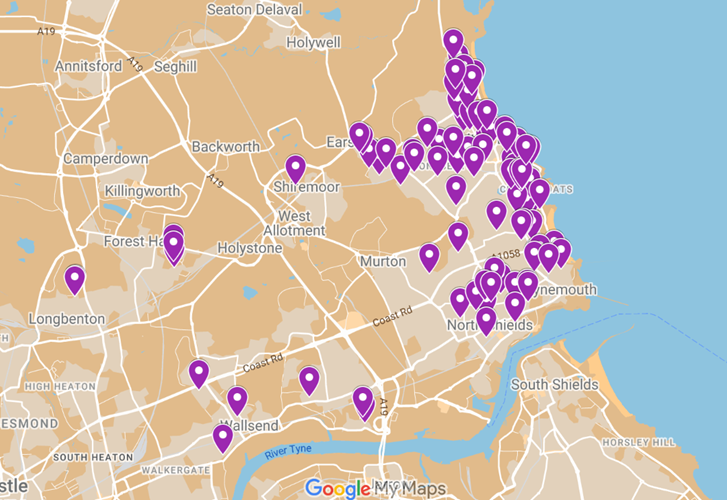

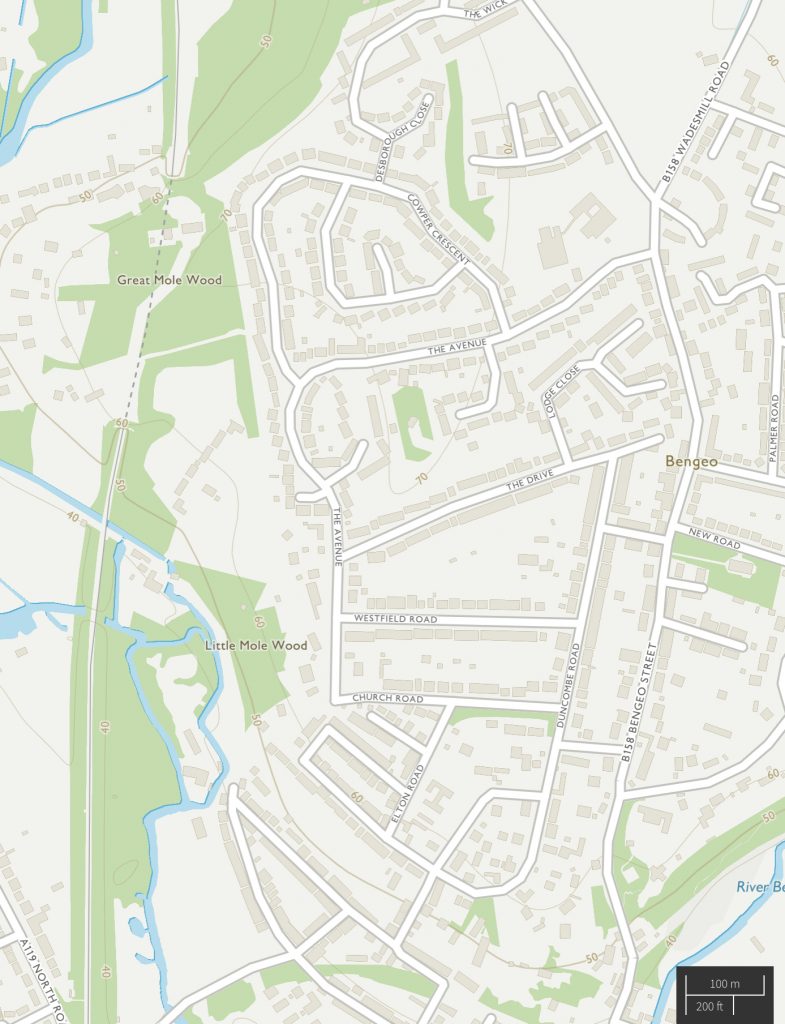

Many of PlayMeetStreet’s streets are concentrated around the coast, in Monkseaton, Whitley Bay, Cullercoats, Tynemouth and North Shields, but we have also supported streets in Wallsend, Howdon, Forest Hall, Longbenton, and Shiremoor (see here for a live map of all our play streets).

PlayMeetStreet is run by unpaid volunteers, who form the committee, promote the scheme, process applications, liaise with the council, support residents, and apply for funding. In addition, those organising play streets on their own street do so as volunteers and commit a considerable amount of time and energy to animating play and community on their street.

In this context, it is important to note that all of this organisational work adds up as thousands of volunteer hours, dedicated to making parts of North Tyneside a nicer place to live.

In November 2022, we circulated an online survey to every person who had been involved in setting up a play street in North Tyneside, from those who organised just one session to those who have been running play streets regularly for up to 5 years, and everyone in between.

We asked for key facts and figures about the play streets and their organisation, for information about the identifiable impacts, and for issues, concerns and obstacles. We also asked about the relationship between play streets and the streets’ experiences of the pandemic.

We received 40 responses, out of a total of 94 streets that have been involved in PlayMeetStreet in some way since 2017. These include streets all along the coast (from St Mary’s to North Shields), but also Wallsend, Howdon and Longbenton, for example.

The full report is available here, but we explore below some of the key findings.

Some of the key, recurring reasons for getting involved in play streets include:

- To create safe space for children to meet each other and play on their doorsteps

- To enable children to learn to cycle safely

- To get to know neighbours better

- To create a sense of community

- To build connections between young families

- Adults fondly remembering playing out as a child

- To build on occasional street get togethers (e.g. street parties, VE day, jubilee)

- To try to calm traffic

- To enable greater independence for growing children

The number of children who join in play streets sessions varies from session to session, and from street to street, but the survey shows that on most streets, between 10 and 20 children normally take part. It is unlikely to always be exactly the same children who participate from month to month, so the total number of individual children involved will be higher than these figures.

Roughly how many children normally take part during play street sessions?

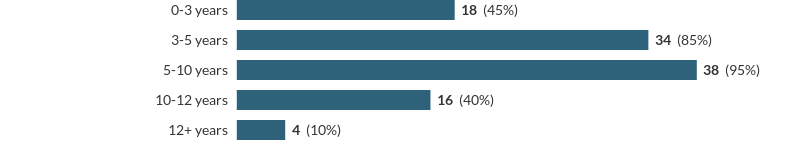

Most children involved are of primary and pre-school age. This has important implications for school readiness, for social and physical skills, and for community-building amongst parents of young children.

Roughly what ages are the children who normally take part in your play street sessions? Please tick all boxes that apply.

PlayMeetStreet play streets are not just for children. They also create a space for community and connection amongst adults. Significant numbers of adults take part (supervising their own children, stewarding, making cups of tea, playing etc.) and these include adult neighbours without young children on the majority of play streets

Approximately how many adults normally take part in your play street sessions?

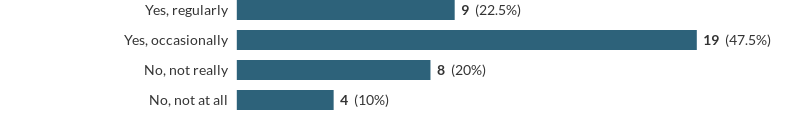

Do adult neighbours without young children join in your play street sessions?

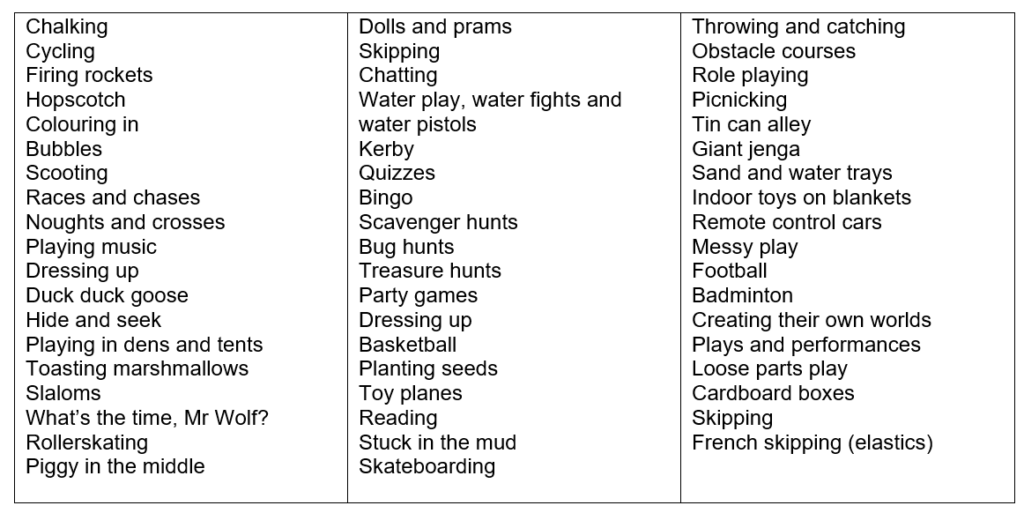

When the barriers are up and the space of the street is safe to play, children engage in hundreds of different play activities, representing most of the so-called ‘play types’.

As well as fun, though, we know that play – across the range of types identified – supports all sorts of physical and social developments for children.

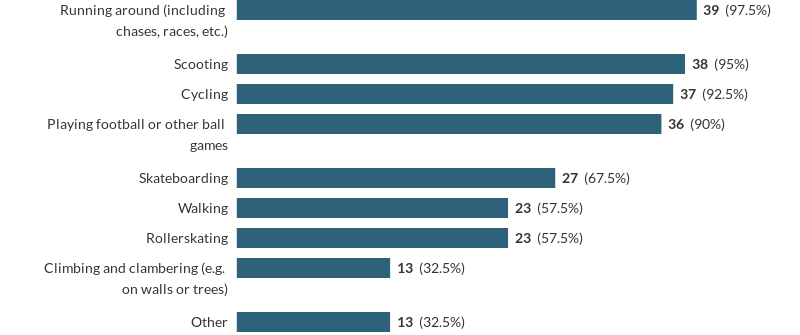

One of the most visible impacts of a play street is on children’s physical activity and skills. Children make the most of the safe space offered to move in all sorts of ways, usually for the full three hours.

In what ways have the children on your street been physically active during your play streets? Please tick all that apply and add ‘others’ as appropriate.

In response to the question “During play streets, do you think children on your street have learnt or improved any physical skills?”, the following percentages of respondents said yes to:

- Cycling 74%

- Scooting 66%

- Skateboarding 47%

- Rollerskating 54%

- Skipping 69%

The impacts on children are not limited to physical skills, however. Play streets create opportunities for children to develop and practice a range of social skills.

During play streets, do you think children on your street have learnt or improved any social skills?

| Percentage stating ‘yes’ | |

| Interacting with children of a similar age | 85% |

| Interacting with older or younger children | 79% |

| Interacting with adults on the street | 87% |

| Learning about road safety | 69% |

Other specific social skills that respondents suggested children had developed included:

- Helping to set up the street for play

- Doorknocking neighbours to let them know about the play street

- Asking neighbours to move cars

- Getting to know the street and adjacent streets

- Taking turns and sharing toys and treats

- Litter picking

- Taking responsibility for younger children

- Extending friendship groups

- Speaking to people (of all ages) who they don’t know well

- Teaching other children games and skills

- Learning to deal with conflict and arguments

- Working as a team

- Listening to adult organisers

- Being polite with neighbours

The impact of play streets on connection, friendliness, safety and belonging on residents is overwhelmingly positive. The vast majority of respondents in North Tyneside noted that, in a variety of ways, their relationships to their streets and neighbourhoods and to their neighbours dramatically improved. The increases in feelings of connection, safety and belonging are incredibly important to families in terms, for example, of their capacity to support each other, to negotiate challenges and crises (such as the pandemic and the cost of living crisis), and to feel at home. Play streets undoubtedly contribute to the council’s stated goal of making North Tyneside an even greater place to live.

| Percentage stating ‘yes’ | |

| I know more people on my street since we started to organise play streets | 93 |

| My street feels a friendlier, safer place to live since we started to organise play streets | 73 |

| Children on my street have made new friends since we started to organise play streets | 76 |

| I feel I belong more in my neighbourhood since we started to organise play streets | 78 |

| I have become friends with neighbours since my play street started | 83 |

As well as the more intangible feelings of connection, belonging and safety, we can identify a range of specific activities that demonstrate a clear growth in trust and support on the borough’s play streets. Respondents reported that five key acts which demand considerable levels of trust (holding spare keys, borrowing equipment, feeding pets, borrowing money, and look after children) all grew in scale since their play street started.

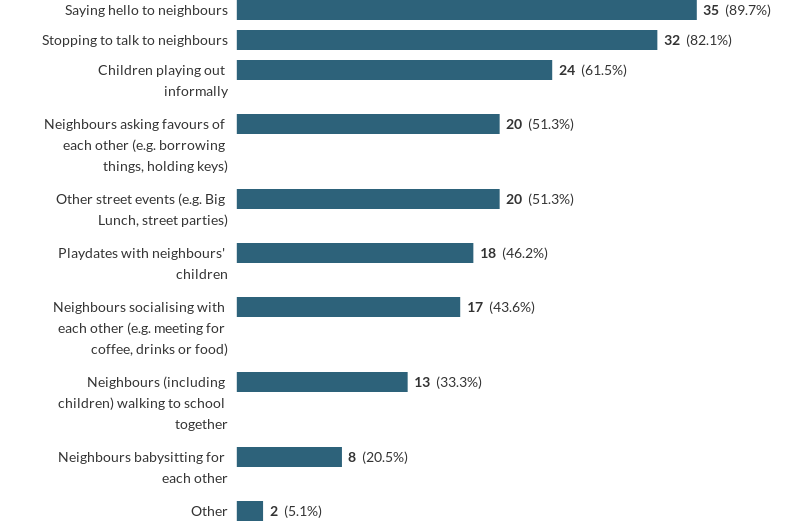

More generally, the responses regarding increases in neighbourliness and connection are overwhelmingly positive. Some of these reaffirm the positive changes outlined above, but it is clear that play streets support neighbours to get to know each other and to support each other in a number of ways. According to respondents, every one of these activities had seen an improvement since streets had started to play out together.

In all these ways, it is clear that the benefits of play streets extend well beyond children and their opportunities for play.

Have any of the following increased in frequency since your play street started? Please select all that apply and add your own examples.

Whilst one might imagine that it is families with children who reap the most benefits from play streets, on 70% of streets surveyed, adult neighbours without young children participate occasionally or regularly. This suggests that these neighbours too, who might not have a particular interest in creating space for play, potentially also benefit from impacts of play streets.

The resident-organisers who responded outlined some of the ways these adults have engaged in, and benefitted from their play streets, and underlined the efforts they go to ensure that all neighbours are invited and included in the play street. One noted, for example, that “We made sure our play streets are for everyone, including adults and teenagers. We want that sense of community.”

Those who reflected on the participation of adults without young children noted that

- elderly neighbours would come out to chat, to share a hot chocolate or some cake

- adult neighbours would express real pleasure in seeing children play on their streets

- at key events (street quizzes or bingo, summer street parties, Christmas, for example) more adults would participate

- many adults without children pop in to the play street or stop to chat as they’re coming and going, even if they don’t stay out

- some adults without young children volunteer to ‘steward’ the road closure, enabling the play street to happen and giving them a chance to chat to other neighbours

- adults without young children will sometimes come along with grandchildren, nieces and nephews, or other young relatives and friends

- others often out gardening, washing cars, fixing bikes while the children and their families play and chat and engage as they do so.

One of the ways in which the community benefits of play streets are reinforced is through the street Facebook and WhatsApp groups that have developed, often as a result of the play street, but sometimes as a first step towards the street establishing a play street.

90% of the streets surveyed have either a Facebook group (10%) or WhatsApp group (77.5%) or both (2.5%). These groups complement the in-person socialising on the street and enable connections to continue between play street sessions. It’s clear that these groups, developed alongside play streets, support residents in all sorts of ordinary but important ways that simply make life easier.

One of the particular ways in which play streets enabled support was during the pandemic. 72% of resident-respondents on streets that had started playing out before the pandemic stated that their play street positively impacted their street’s experience of the pandemic. Some of our play streets also emerged out of the pandemic, as a way of consolidating and developing the connections and informal support networks established during the pandemic and as a reflection of how the streets felt during and after lockdowns.

Play streets also enable other forms of very local engagement and activism. A significant minority of streets have also got involved in activities such as litter picking and tending their nearby green spaces. A number have also participated regularly in the Tin on a Wall collections for local charities and other collections for food banks etc. Almost half of the streets involved have started conversations more generally about their streets. These include speaking to their councillors about speeding, parking and pavement repairs, training as speed awareness volunteers, and speaking to other road users (e.g. neighbouring schools and clubs) about driver behaviour.

Asked to reflect on the sorts of changes organisers have seen on their streets since they started running play streets, a number of themes recurred:

- Much closer relationships with many neighbours

- Stronger community

- Improves sense of security/safety

- Children of all ages know each other

- Neighbours just chatting and saying hello to each other more and more.

For organisers, some of the best things to happen on their play streets included:

“elderly neighbour now brought a hot meal every evening”

“Street Play has increased the ‘neighbourhoodness’ of the street. Many of us (adults) are now close friends and organise social activities together”

“There was a real community feel again after the long Covid months”

“The 100th Birthday party for our neighbour D___ which included the Backworth Colliery Band playing for us; the sense of community and knowing everyone better”

“Regular playing now in front gardens as well as in the back alley”

“Feels like a little community & more united. Look out for each other a lot more”

There’s more on all of this in the full report here.

[1] Figures for each street vary, we estimate 15 children and 10 adults per street. This is a more conservative estimate than that from a national survey (2017, 2019 and rechecked 2021) which suggests the following participation averages for play streets: 30 children attending and benefitting, and 15 adults actively involved in the play street.