As I suggested in my first post-holiday blog, the first mile of our holiday by bike – from our home to the North Shields ferry port – was, by a long margin, the worst. Things could only get better – and the decent, safe cycling infrastructure I’d been fantasising about started within metres of the ferry at the other end, in IJmuiden.

A friend had given me street-by-street directions through IJmuiden, before we picked up the fietsknoopen network we’d be following for longer distances. Her directions even let me know when I’d come across my first “Dutch roundabout”. Dutch roundabouts (I’m sure the Dutch just call them roundabouts) are particularly topical for me and my fellow North Tyneside walking and cycling campaigners, as our council is in the process of attempting to create one of the first in the UK, much to the annoyance of our local Conservatives. More on this later.

For this short route through IJmuiden, we travelled along quiet streets, designated fietstraaten, on separated cycle paths (fietspaden), round “Dutch” roundabouts, across raised, prioritised crossings. At no point, despite not knowing my way and never having cycled in the Netherlands before, and even with a heavily-laden bike, my daughter on board, and another bike being dragged behind, did I ever feel unsafe or at risk.

As my daughter began to foresee a 16-day field course in Dutch cycling infrastructure, I marvelled at the separation, the priority, the safety, the smoothness, and the ease of the paths we were travelling, getting particularly excited at a stretch of path which sailed around a mature tree. I felt sure that at home this tree – and its roots – would have been left as obstacles to navigate on an unbending path.

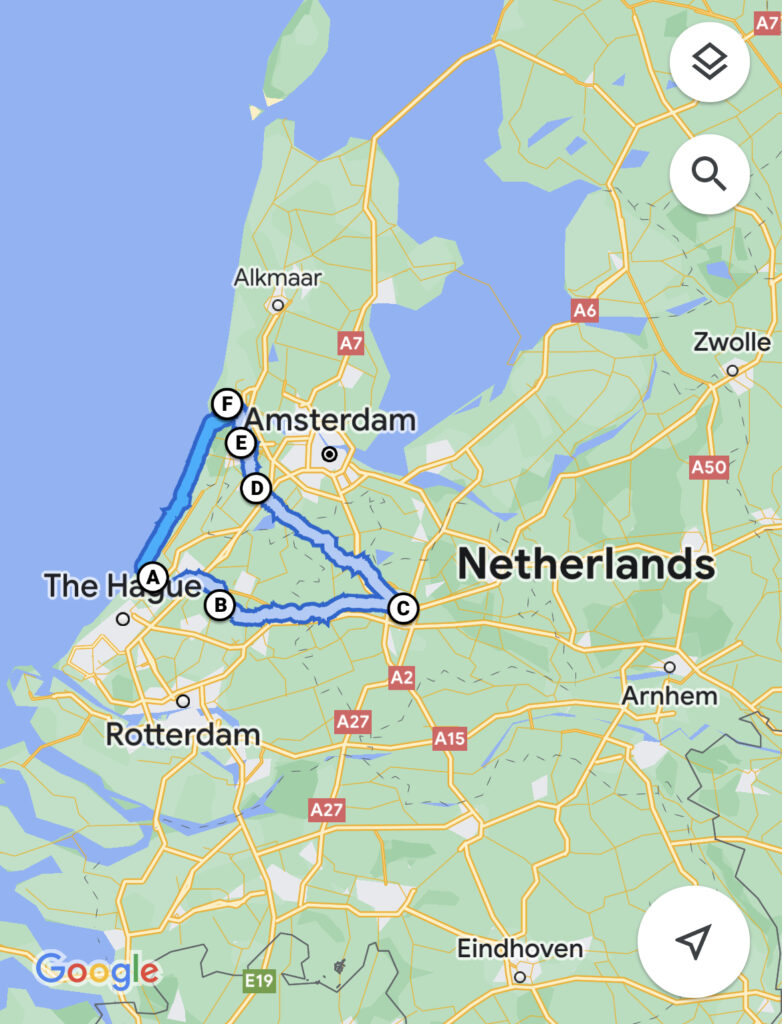

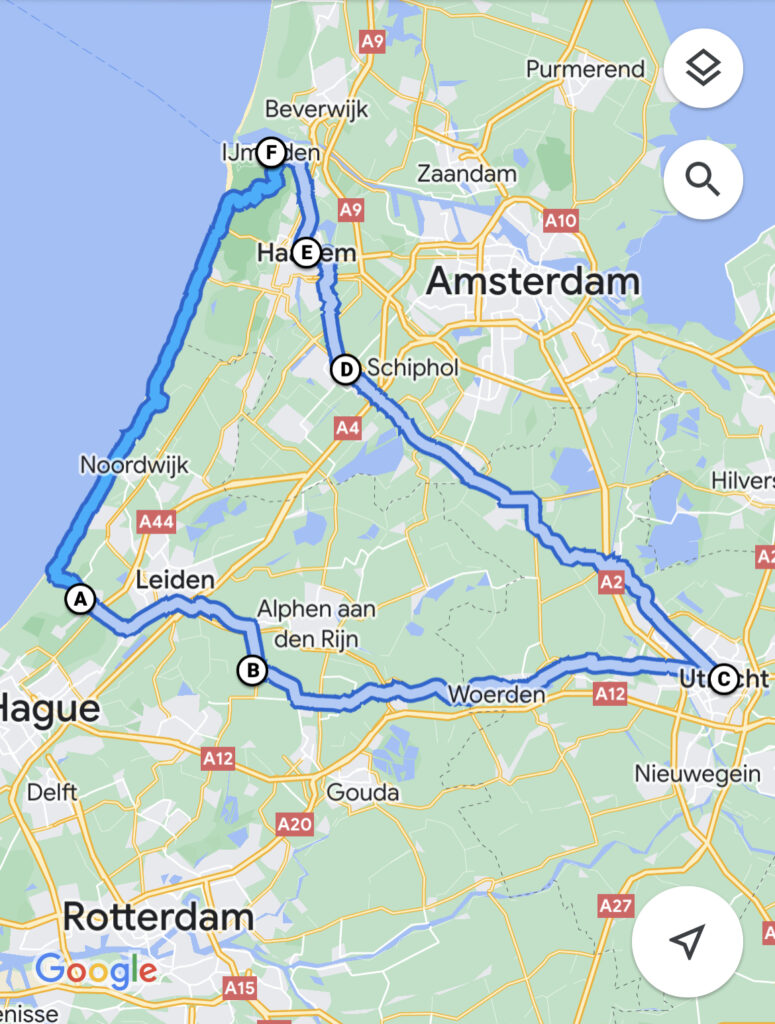

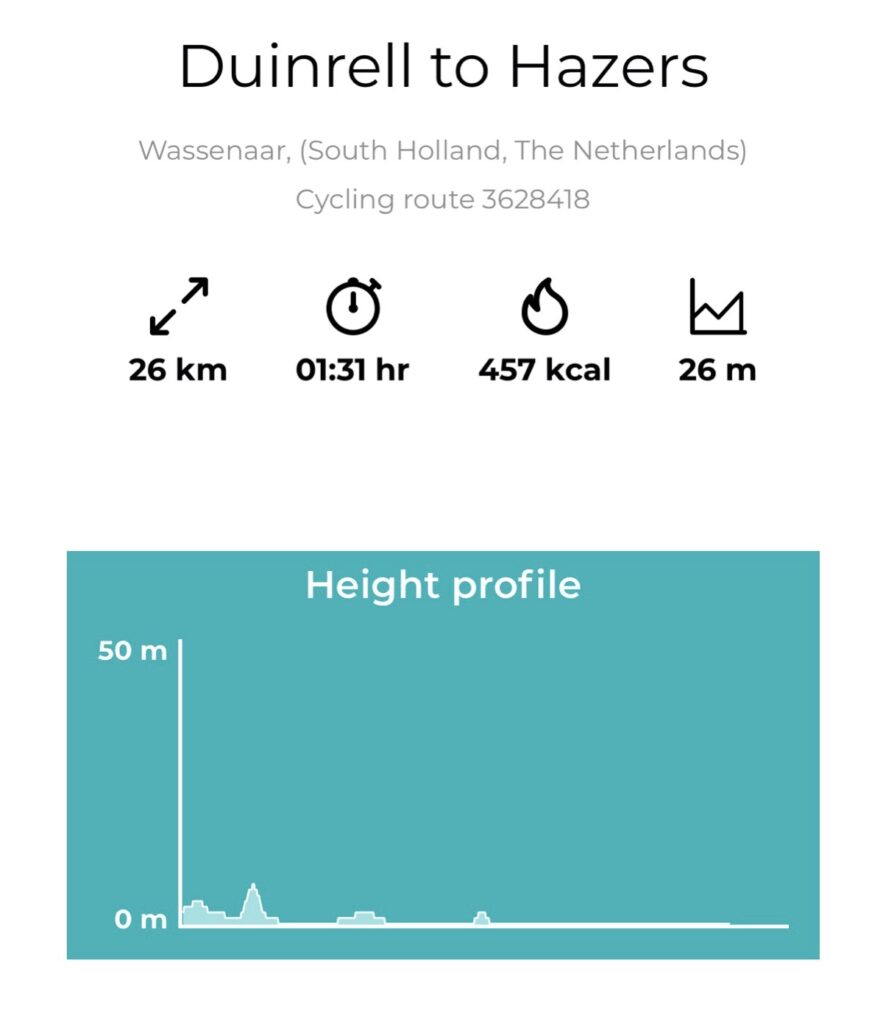

Within about 15 minutes of leaving the ferry, we reached our first knooppunt, which was to lead us south through the dunes and along the seafront on the Netherlands’ west coast. This stretch is known for its winds and we were lucky that it was quite still, but we’d also been primed to expect a much less flat landscape than the Netherlands is known for. The paths were beautiful, spacious, and high-quality but they were also undulating; the route profile for this ride was markedly more demanding than any other. None of the hills was big or long, but they were many of them. Yet, the paths were busy with tourist and tourers, but also with older people and families, who seemed to simply be getting from one place to another.

Between the long stretches through dunes, we passed through seaside towns reminiscent of those in North Tyneside. Noordwijk reminded me of Whitley Bay, with its long prom, its ice cream parlours, and slightly faded hotels, but its seafront cycle path was wide, separated, direct, and uncontested, and so too were those of all the other coastal communities we passed through. It was a pleasure to cycle, with one eye on the sea, knowing we weren’t going to collide with pedestrians, dogs on long leads, or scooting children.

In the course of the two weeks that followed, we cycled on urban, suburban and rural routes, for distances from a few hundred metres to up to 20 miles, on a range of different bikes. As I explore below, we didn’t feel safe all the time, but the moments of anxiety were more about us than about the infrastructure around us. On cycle paths, quiet streets, rural roads, at roundabouts and junctions, we travelled easily and with a lot of pleasure.

In residential neighbourhoods, we cycled along separated cycle paths, fietstraaten (where “the car is a guest” [auto te gast]), quiet routes with painted paths on each side, through woonerven (living streets) and past not only homes, but also schools, shops, playgrounds and parks. As someone who is particularly engaged in thinking about residential streets and what we do on them, these meandering journeys, often following trails of knooppunten through what seemed like very ordinary streets, were particularly appealing, to see what a different scale and pace of movement could feel like in enabling both everyday mobility and a quietly-animated street life.

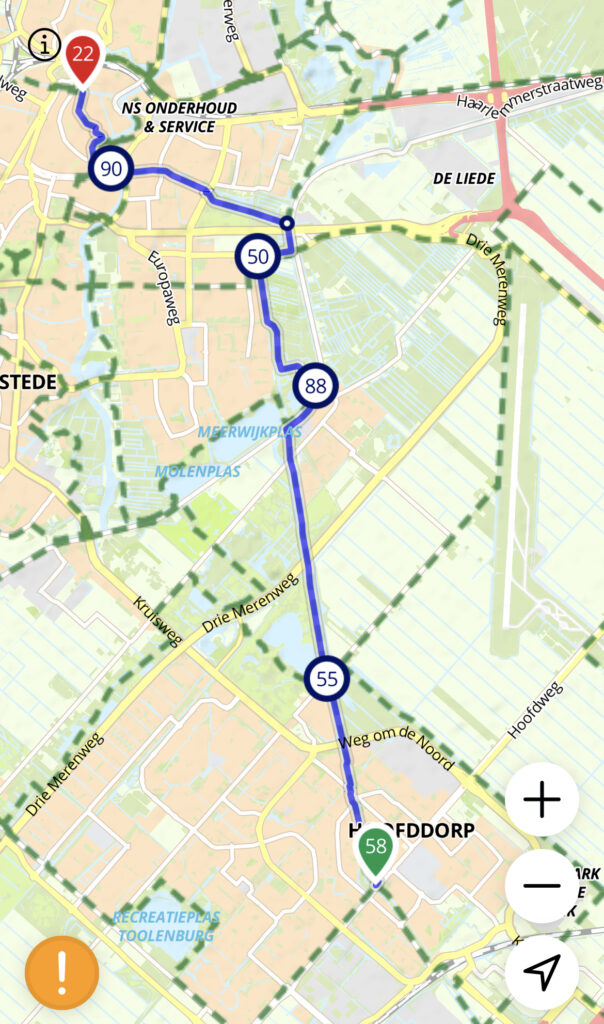

At a slightly bigger suburban scale, later in our trip, some of the links between towns closer to Amsterdam that almost merged into each other – Hoofddorp, Haarlem, and back to IJmuiden – showed what’s possible for the kind of everyday infrastructure that seems to allow residents to travel for half an hour or so to work, or a busier high street, or to see friends or family. Less meandering, these suburban routes followed main roads, but with a degree of separation and safety a long way from the arterial routes imagined where I live. The North Tyneside variant are more likely to be shared paths on narrow pavements, with no protected junctions, and few onward connections. The suburban routes we followed in the Netherlands allowed us to make quick, safe progress, as directly as we might if we were in car.

On more rural stretches, we often found ourselves following canals or through polders on dead straight paths, often bidirectional, with or without median markings. Occasionally we were expected to share these with farm vehicles, but we saw just one tractor. Otherwise, our fellow travellers were families, teenagers, older people, and some more middle-aged commuters. On these stretches, we saw a lot of older people, men and women, on ebikes, as well as parents riding ubiquitous Urban Arrows with children on board. We were following knooppunten, but most of those cycling alongside us seemed to know the routes well, suggesting they were making ordinary journeys between everyday places; these were short, but connected, routes between small towns and villages, making travel by bike over short-to-medium distances safe and straightforward.

In the most urban areas, including in the city centre in Utrecht but also in the centres of Haarlem and IJmuiden, the cycling network is perhaps more like a jigsaw, made up of connected pieces but with visible joins. In most places in these contexts, rather than following continuous paths, journeys were made up of short stretches of quiet, often one-way, streets, linked by protected junctions to sections of fietspaden (separated cycle paths) and dedicated infrastructure such as bridges and underpasses. There were also, of course, far more cyclists. And all this meant that these were the most challenging environments for us to cycle in.

It wasn’t that the infrastructure wasn’t good or consistent, but that the nature of cycling in these places was less familiar. We weren’t used to having to respond quickly to different cycling conditions or to negotiating with hundreds of other cyclists heading in all sorts of different directions, and we weren’t used to exercising our priority over cars, especially at junctions where ‘sharks teeth‘ indicated drivers must – and did – give way to us. We hesitated, expecting to have to double-check that drivers would give way, as we have to at home, and frustrated other cyclists and drivers. It took us a while too to learn the road signs and the Dutch word uitgezonderd (‘excepted’), working out when we could and couldn’t cycle the ‘wrong way’ down a one-way street, through a ‘dead end’, or on a pedestrian route, or when to expect cars, taxis and vans on what seemed like a fietstraat, and all these challenges were much more prevalent in the busier urban areas.

As a result, we had a few more close passes and more aggression from other road users as we got used to this kind of cycling, and my anxiety was higher as I tried to keep my daughter safe on her bike.

But, once we started to get to grips with all of this, and find good routes for the journeys we repeated, we revelled in the convenience of cycling quickly to the shops, the station, to cafes and restaurants, and in the sheer pleasure of joining thousands of others cycling on their daily routines. We loved pulling up outside a shop or cafe and just securing our bikes with ‘Dutch’ locks, filling our panniers with our purchases, and heading home.

I’ve already talked a bit about junctions, and I suppose the key thing, in contrast to at home, is that cyclists nearly always have priority at junctions (though usually have to give way to pedestrians, in an appropriate hierarchy of road users). This is true when cycle paths cross roads to head in another direction, or simply to the other side of the carriageway, but also at roundabouts where a cycle path, with priority, takes cyclists round and off the roundabout safely without stopping. My experiences of these roundabouts confirm to me that, despite our local Conservatives fears, North Tyneside’s new roundabout is not Dutch (see this also). In all these instances, it took us some time to feel confident that we could simply just carry on, that drivers would give way to us.

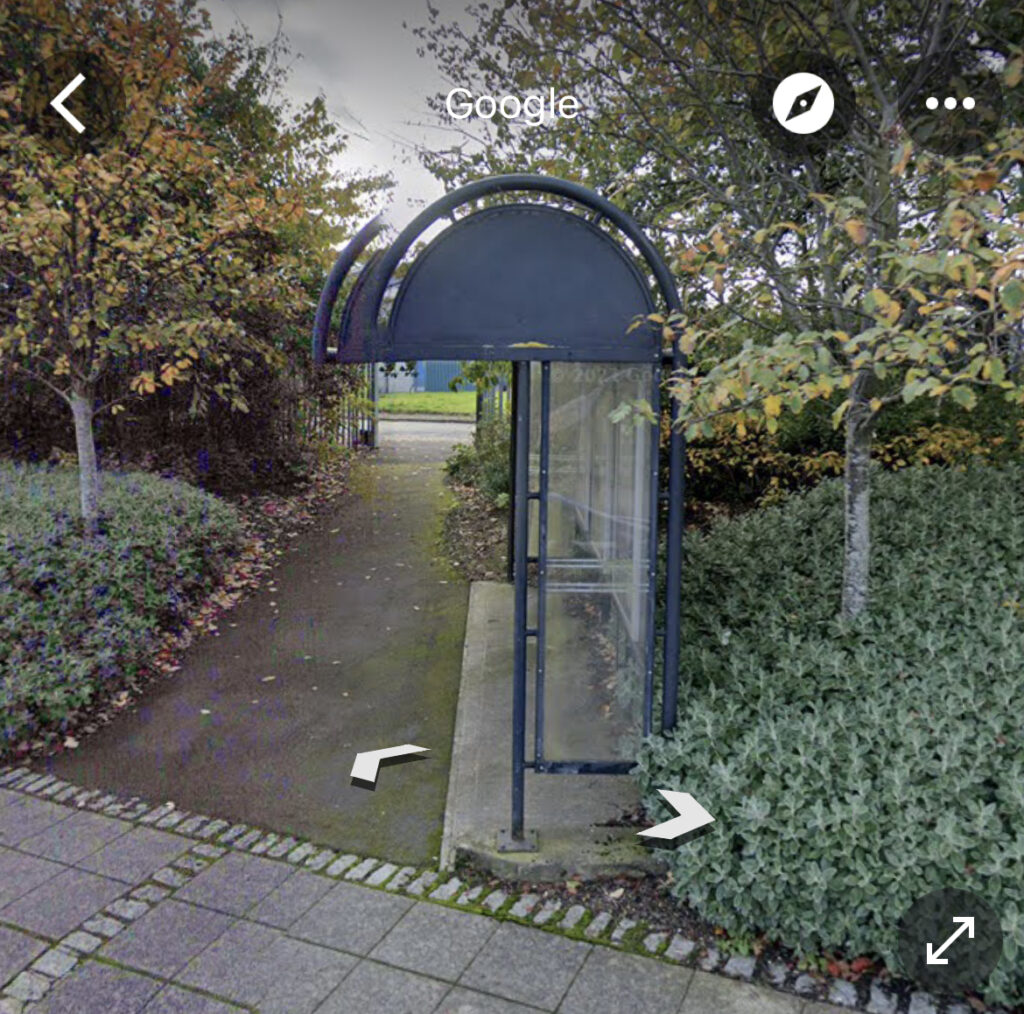

We crossed a good few bridges and underpasses too. The preference seems to be for bridges when crossing bigger roads, canals and railway lines, following perhaps the principles of social safety that ensure that a path feels safe from the perspective of visibilty. After many miles on flat paths, these sometimes-steep paths over bridges felt like hills to my daughter as we approached, but in fact they were never too steep or too long for her untrained legs; the angle and the steepness sometimes got me on my Tern GSD as I lost momentum with a heavy bike and the wrong gear, but I learnt my lesson and prepared my approaches better. We got to see some beautiful bridges and to witness a few open.

The few underpasses we experienced were wide, open and light – and well-used, in marked contrast to the dark, narrow, deserted underpasses I sometimes have to navigate on my regular journeys at home. I never felt unsafe in a Dutch underpass and they served a purpose in keeping us on direct routes.

Junctions, bridges and underpasses serve as key points in dense, consistent, connected and safe networks. And this is the heart of my experience of Dutch cycling infrastructure: you can get where you want to go safely and straightforwardly, whether that’s half a mile to the supermarket, seven miles to the next town, or 35 miles to your next holiday accommodation. It’s a remarkable achievement, and one we know didn’t happen without a fight, even in the Netherlands.

What this kind on infrastructure facilitates, affords, for me, is a shift in pace, scale and rhythm. You can get where you want to go, quickly and directly if you want to, or slowly and sociably, if you prefer. You can travel with encumbrances – children, shopping, surfboards, friends – because you don’t have to worry about the risks of being distracted or unbalanced, and because you’ve been brought up to be able to cycle like this. And because it’s possible – even easier – to get around by bike, you can remove cars from spaces which are filled with people, in city centres and residential neighbourhoods, and these places can feel more human; you can feel more human.

I don’t want to present an idealised account of Dutch life; I got a tiny glimpse, very much viewed through bike-shaped spectacles. Cycling infrastructure is just one part of Dutch society, albeit one connected to so many other spheres. But I liked what I saw and what I felt, and I’d like to explore it some more.