Maternity Tales is a three-year research project lead by Dr Emma Cheatle at Newcastle University. It looks at the buildings and interior spaces used for childbirth in England from the seventeenth century onwards, and evaluates their impact on the development of maternity practices.

In this post, Dr Cheatle gives a short history of maternity spaces and talks about her contribution to this years Being Human Festival.

Until the 1750s all births took place at home – except of course where birth occurred unexpectedly! A labour and the recovery afterwards were known as ‘lying-in’. The lying-in period was typically a month, during which the new mother at first recuperated bed-bound, then remained in the house, gradually returning to her household duties. Lying-in ended with the public cleansing and thanksgiving ritual of ‘churching’ performed in the local Church of England.

Lying-in did not take place just anywhere in the home but involved carefully remaking the master bedroom into a dark and airless lying-in chamber. At the first signs of labour, extra linen was draped onto and around the bed and over the windows and doors. The fire was stoked up, and all openings in the room closed – sometimes even gaps and the keyhole were stuffed with fabric. It was thought air and light were harmful, and may lead to the dreaded puerperal fever, a tremendously dangerous illness (essentially an infection) experienced after childbirth. Men were removed from the room, and replaced by a gathering including the midwife and at least five women to aid the birth, called the ‘gossip’. The room was darkened further after birth, as it was thought light could damage the new mother’s eyesight, already weakened by the effort of childbirth.

Jane Sharp, The Midwife Book, 1671, detail of frontispiece

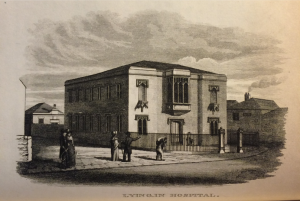

From the 1750s the domestic spaces of home birth were made complex by the emergence of lying-in hospitals. These were the first specialist hospitals, and began an era of institutions in general – from spaces of welfare such as asylums and hospitals to those of intellectual gathering like the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle and the Royal Society in London. The lying-in hospitals were philanthropic charities aimed at poor (albeit married) women who lacked the funds to afford decent homes let alone good midwifery care. Although they undoubtedly helped many women, the lying-in hospitals were devised and controlled by the new men-midwives to develop their skills and establish their status. At first occupying large houses, as the century progressed they acquired purpose made buildings. In contrast to the dark and airless domestic lying-in chamber, these were lofty and neo-classical designs, with roomy wards of 6-8 beds and large windows. Their advantages – including light and airy spaces, access to new forms of care and spaces of rest – contrasted with their disadvantages – lack of privacy, a shift in control over one’s own body as it was passed to the institution, the medicalisation of birth and an increased death rate from puerperal fever.

Newcastle Lying-in Hospital, 1825

From Tom Faulkner and Andrew Greg, John Dobson, Newcastle architect 1787-1865 (Tyne and Wear Museums Service, 1987)

Across the nineteenth-century, birth witnessed various experimental practices in these purpose made spaces. Men-midwives were gradually renamed accoucheurs and then obstetricians. Although the vast majority of women continued to give birth at home – indeed it was not until the 1940s that more than 50% women gave birth in hospital – midwifery care had shifted, and the practices and ideas tested in the hospitals affected home delivery. Light and fresh air were seen as important. Instruments such as midwifery forceps became more common, and men began to be called into the birth chamber in favour of the traditional female midwives, particularly by the middle- and upper-classes.

The Maternity Tales Listening Booth at the 2016 Being Human Festival

Parts of the Maternity Tales project are being presented in an installation which can be seen at this November’s 2016 Being Human Festival. The installation, taking place at the Laing Art Gallery and Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, presents a ‘listening booth’ to explore the history of maternity. Aimed at parents to be, parents, grandparents, midwifery/obstetric professionals, plus anyone interested in architectural and maternity history, the booth comprises two parts:

[1] Histories: Visitors are able to explore a tall wooden filing drawer unit containing different visual displays and sound pieces on the history of spaces used for birth from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

[2] Collections: Visitors are encouraged to fill in record cards found in one of the drawers, in order to explore and share their own labour experiences as ‘spatial maternity stories’. Willing participants are also invited to make sound recordings in a separate screened private interview space. Both these collections will inform Emma’s further research and a radio play.

References:

Doreen Evenden, The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London (Cambridge, 2000)

Ralph A Houlbrooke, English family life,1576-1716 An Anthology from Diaries (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989)

Pam Lieske, Eighteenth-century British midwifery (Pickering and Chatto, 2007)

Adrian Wilson, The making of man-midwifery,1660-1770 (Harvard University Press, 1995)

Margaret Connor Versluysen, ‘Midwives, medical men and “poor women labouring of child”: lying in hospitals in eighteenth century London’, in Helen Roberts (ed.), Women, health and reproduction (Routledge, 1981), pp 18–24.

Helen King, Midwifery, obstetrics and the rise of gynaecology: the Uses of a Sixteenth-Century Compendium (Ashgate, 2007)

Dr Emma Cheatle is Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Newcastle University Humanities Research Institute. She is an architectural historian and writer, and author of Part-Architecture: The Maison de Verre, Duchamp, Domesticity and Desire in 1930s Paris (Routledge, 2017). Her current project presents a critical history of maternity spaces and examines how the past changes our understanding of contemporary experience.