Newcastle University Stage 1 architecture student drawings for The Chair & the Figure are currently on display at the Shipley Art Gallery until 30 March 2017. In this post architecture Teaching Fellow and project lead Elizabeth Baldwin Gray outlines how the project developed.

*

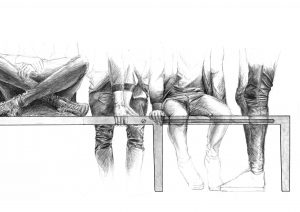

The original work produced for a two-week project consists of large-scale 1:1 pencil drawings of chairs ranging from the Bishop’s throne and Quire Stalls at Durham Cathedral to Marcel Breuer’s Wassily and Long Chair, as well as an Eames chair and ottoman, alongside contemporary chair designs presented to the students by Newcastle furniture designers. The original Marcel Breuer chairs, accessible to the students thanks to the Shipley Gallery, are extremely rare design objects. The ability to interact with these design objects at Shipley Gallery was an invaluable opportunity for our students.

The Chair & the Figure introduces the mechanics of technical drawing, while at the same time helping students become more aware of changes in design attitudes and style over time. The project also explores the relation between chairs and the human form, a conceptual standard of measurement or ‘module’ for architecture in treatises and figures ranging for Vitruvius and Da Vinci to Dürer and Le Corbusier. By examining, measuring, and drawing a chair, groups of students carefully record how the dimensions of a static design element, the chair, are informed by the proportions of the human body. This work serves as the basis for original architectural design in later individual projects.

exhibition image

The students began with analytic sketchbook studies of the Platonic ‘form’ of a chair: plans, sections, and elevations, as well as exploratory 3D sketches. Working in groups of three or four, they then produced 1:1 drawings of various specific chairs they had been assigned to study. Each student was responsible for one A1 board, to be combined with two or three others from the other members of his or her group to form a single large drawing. Groups presented these collaborative drawings at their final review, together with research into the history of the chair under study. The text that accompanies each of the chairs was written by the students and reflects this research, detailing the social and economic conditions in which the chairs were designed and manufactured. The framed images on display at Shipley Gallery are excerpts from large collaborative drawings, reproduced and displayed to give a sense of the overall range of drawings presented at the final review.

A dedicated group of student curators, Assem Saparbekova, Vito Benjamin Sugianto, Natalie Lau and Iris Xin Guo, guided by Elizabeth Baldwin Gray, worked hard following the project’s final review in October/November 2016 to make the exhibition happen. Together the exhibition team came up with a plan for how to display the work in the space made available by Shipley Gallery through Education Director, Morgan Fail. From initial brain-storming sessions to measuring and drawing the space at Shipley, to coming up with a design layout, to physically installing the exhibit with the help of Newcastle University’s Sean Mallen, the experience was a true introduction into curatorial exhibition design and assured that the display would truly reflect the range of student work produced and the learning experience of the project.