Neuroeducation is an emerging educational discipline where a neuroscientific understanding of how the brain learns is used to drive forward current teaching methods or to develop new and innovative methods of teaching and learning. Whilst neuroeducation does not claim to be a complete solution, it is hoped that an increasing knowledge of the biology behind the process of forming memories in the brain will make teaching methods more efficient.

Neuroeducation is an emerging educational discipline where a neuroscientific understanding of how the brain learns is used to drive forward current teaching methods or to develop new and innovative methods of teaching and learning. Whilst neuroeducation does not claim to be a complete solution, it is hoped that an increasing knowledge of the biology behind the process of forming memories in the brain will make teaching methods more efficient.

Unfortunately there are also a number of ‘neuromyths’ prevalent in education and these have ‘muddied the water’ and tarnished the image of neuroeducation. Examples of neuromyths include the ‘right brain creative/left brain logical’ idea as well as the concept of distinct ‘learning styles’. Current research in the field therefore aims to utilise real scientific evidence to help debunk neuromyths but also to provide an evidenced-based approach to develop techniques that tap into the brains’ own method of forming memories in order to enhance learning.

Spacing out learning over a period of time and into ‘bite-sized’ chunks is not a new idea. It has long been known that repeated learning at intervals, following an initial learning event, aids learning progress. Revisiting a topic shortly after teaching reduces the chances of forgetting information and increases the possibility of the brain forming long-term memories.

Spaced Learning is a technique that hopes to tap into the process of long-term memory formation by scheduling multiple short periods of teaching interspersed with breaks. In the breaks students complete activities that require little thought and are unrelated to the taught topic. The length of time of the teaching periods, and the breaks in teaching, are designed to consolidate learning at key points in the physiological memory formation process. Spaced learning has been tested as a teaching tool by Kelley and Whatson in 2013 and has recently been included in the Open University’s 2017 ‘Innovating Pedagogy’ report that proposed ten up-and-coming innovations in teaching that have the potential to alter educational practice.

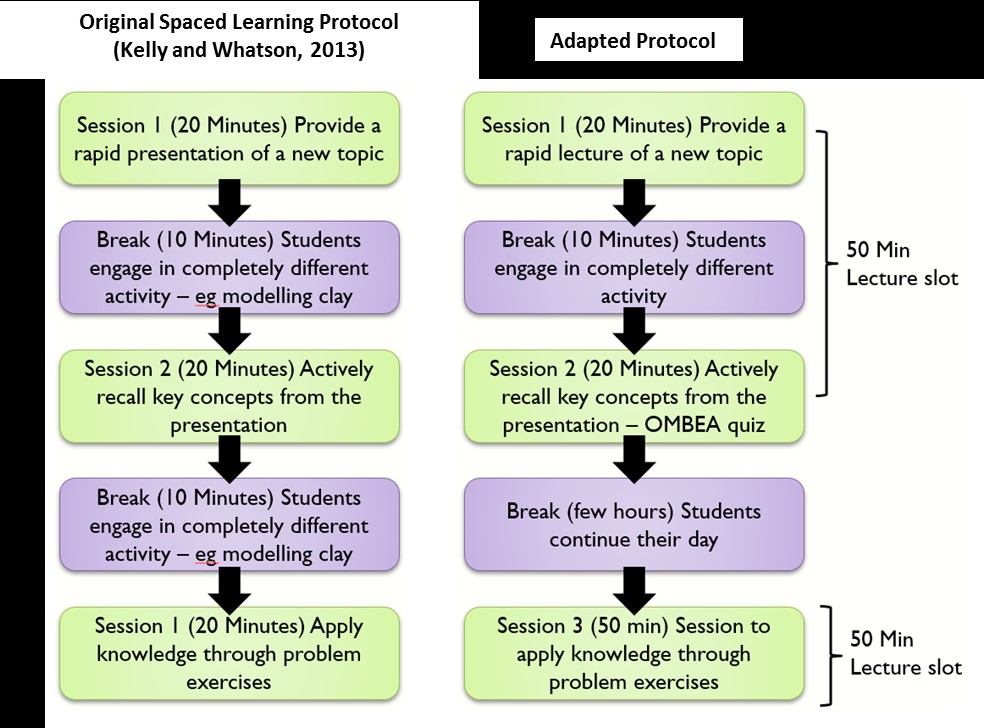

Most studies relating to neuroeducation techniques are trialled in a school environment but very rarely get trialled in higher education. It is therefore unknown whether such techniques can be adapted for use in higher education. I therefore aim to trial a form of spaced learning during the MBBS curriculum to see if there is scope for it to be used as an educational technique in higher education. The original study on spaced learning by Kelly and Whatson used a 90 minute teaching session that included three 20 minute teaching slots separated by two 10 minute breaks. This is outlined on the left side of the image. To work with the traditional 50 minute lecture based timetable it is proposed to run two 20 minute teaching sessions with a 10 minute break in between, followed by a second session later in the day (right side of the image). Feedback will be gained from students on their experience of this style of teaching with the view that a more extensive study may be developed in future.

Most studies relating to neuroeducation techniques are trialled in a school environment but very rarely get trialled in higher education. It is therefore unknown whether such techniques can be adapted for use in higher education. I therefore aim to trial a form of spaced learning during the MBBS curriculum to see if there is scope for it to be used as an educational technique in higher education. The original study on spaced learning by Kelly and Whatson used a 90 minute teaching session that included three 20 minute teaching slots separated by two 10 minute breaks. This is outlined on the left side of the image. To work with the traditional 50 minute lecture based timetable it is proposed to run two 20 minute teaching sessions with a 10 minute break in between, followed by a second session later in the day (right side of the image). Feedback will be gained from students on their experience of this style of teaching with the view that a more extensive study may be developed in future.

For further reading, please see:

Kelley, P., & Whatson, T. (2013). Making long-term memories in minutes: a spaced learning pattern from memory research in education. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 589. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00589

The Open University (2017) Innovating Pedagogy 2017 [online] available from http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/innovating/