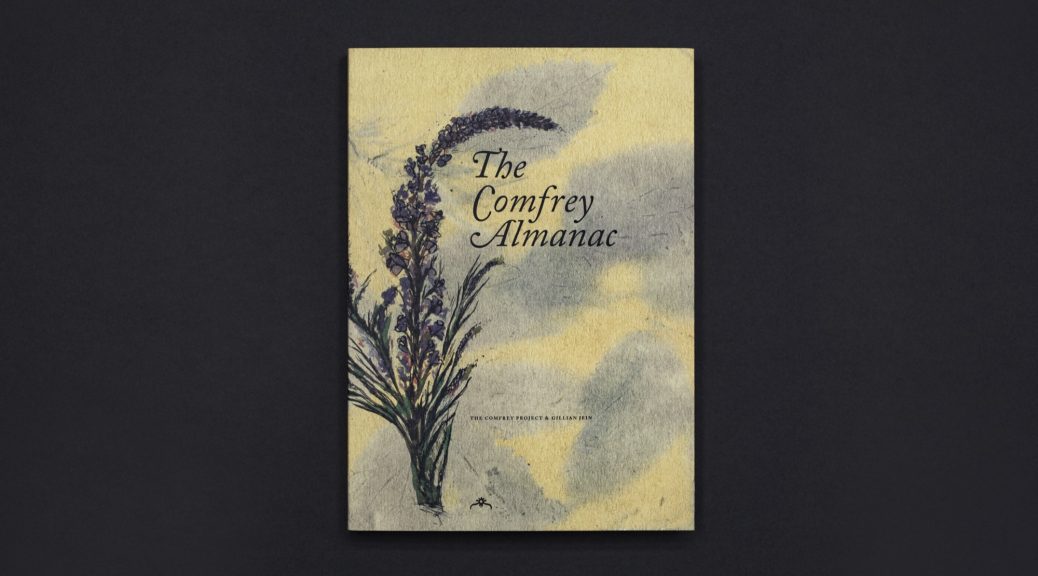

Almanac book design by RonanDevlinStudios

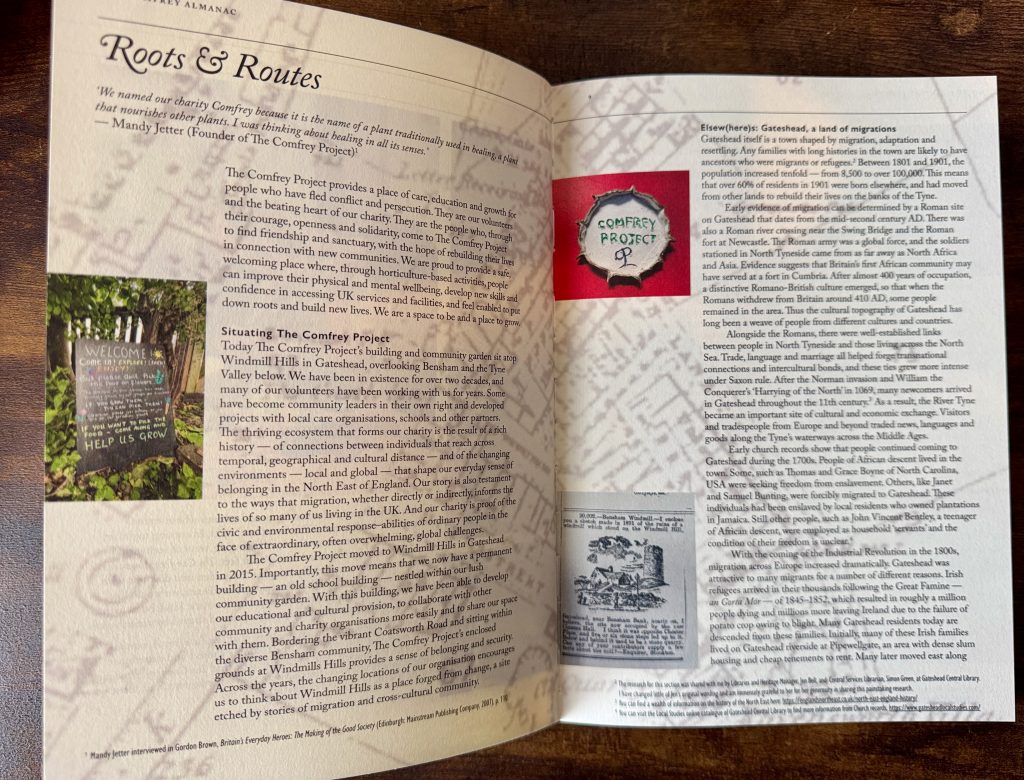

The Comfrey Almanac is a collaborative book project and resource developed in partnership between The Comfrey Project and Newcastle University.

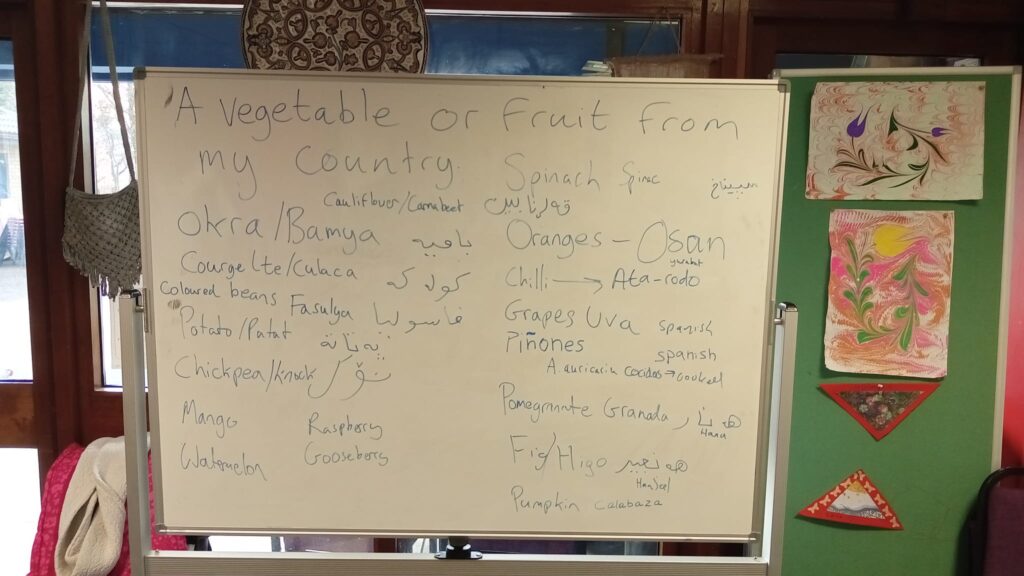

Created by and for the volunteers of The Comfrey Project, the book curates the diverse socio-ecological knowledges and expertise of the project’s members, many of whom have experienced forced migration and are now putting down new roots in communities across the North East of England. The book is intended to provide a lasting structure to document and share this knowledge, which has been cultivated at The Comfrey Project since its establishment by Mandy Jetter in 2002.

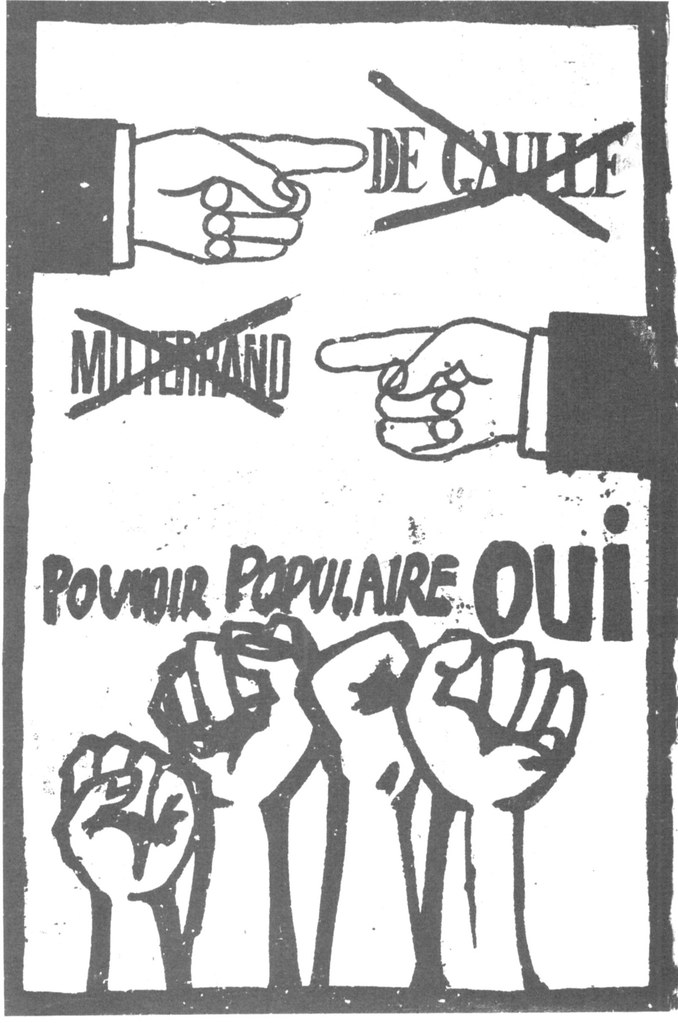

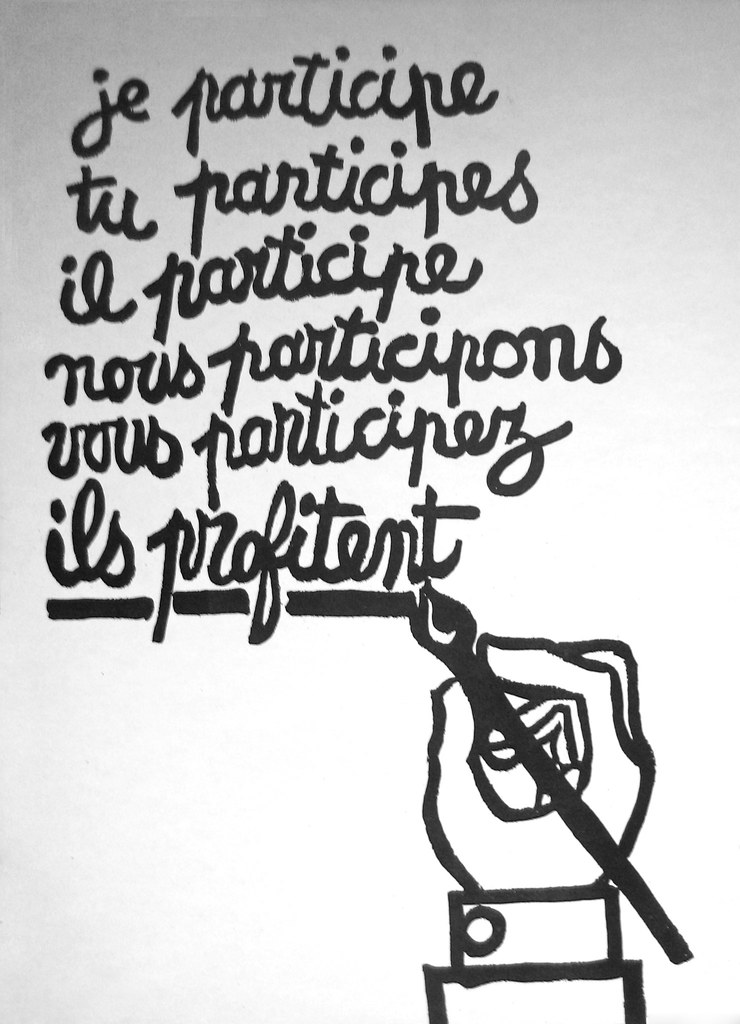

In a hostile political context, the tangible artefact of The Comfrey Almanac amplifies the volunteers’ voices, enriches educational literature, and our capacity to address social equity and environmental sustainability creatively and collectively.

The book can be purchased via our online store and all proceeds go to support the work of the charity.

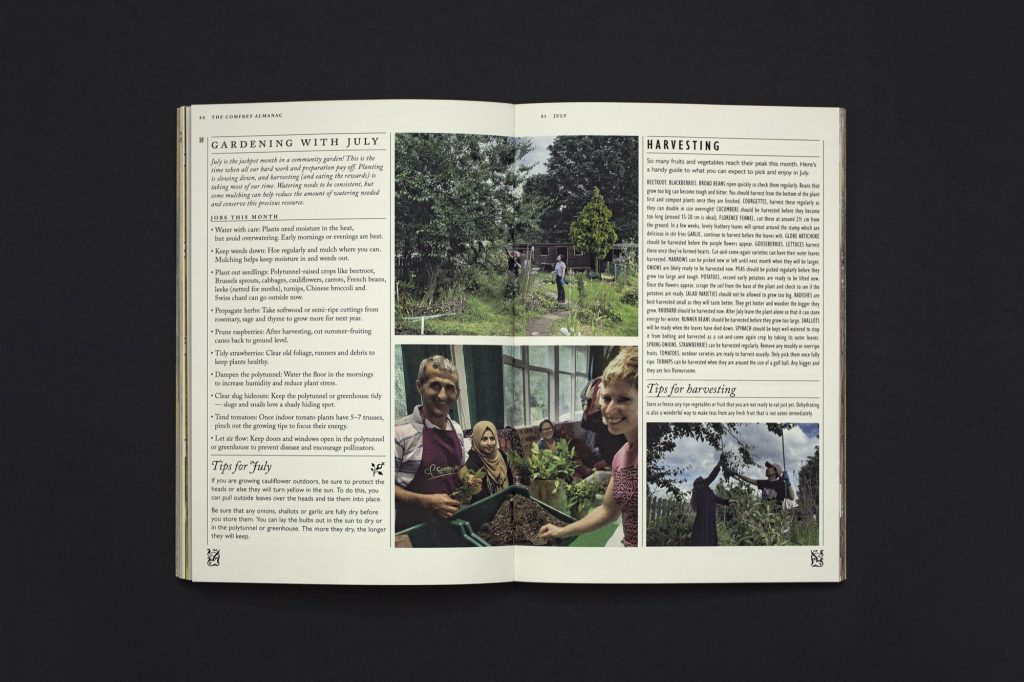

Challenging the often monocultural formats of more traditional almanacs, our book accommodates transcultural perspectives on land use, and is organised into twelve chapters corresponding to the months of the year. In the interest of sustainability the book maps the months and seasonal rhythms of the year, but is not mapped to any single calendar year. Each monthly entry includes:

1. Festivals and important dates from around the globe (e.g., Basant, Ramadan, Nowruz, Eid al-Fitr, Refugee Week, Christmas)

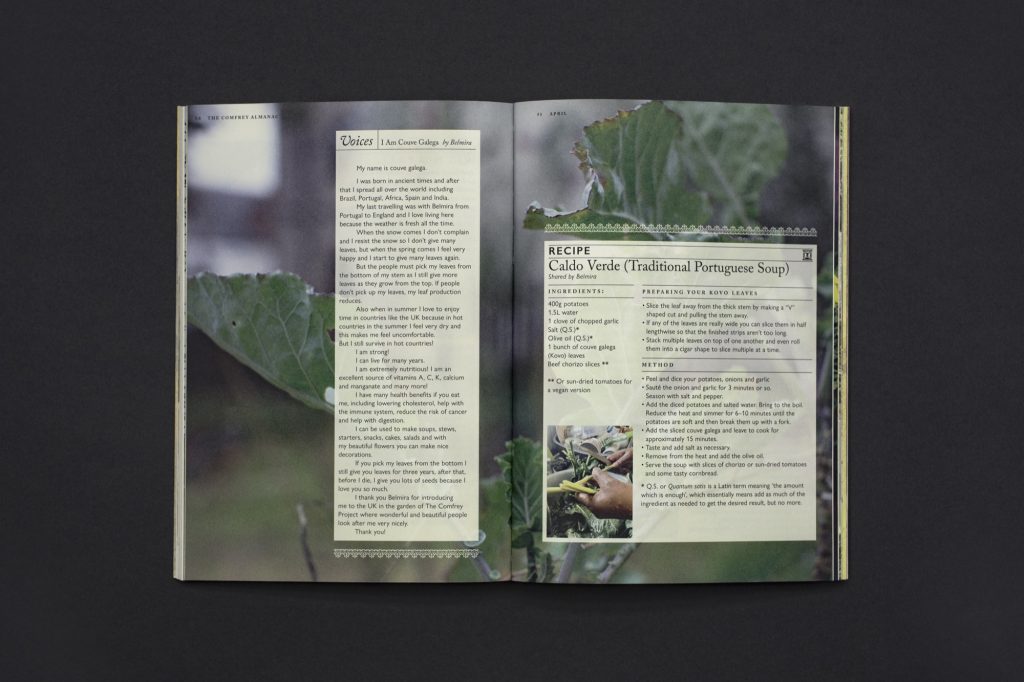

2. Voices

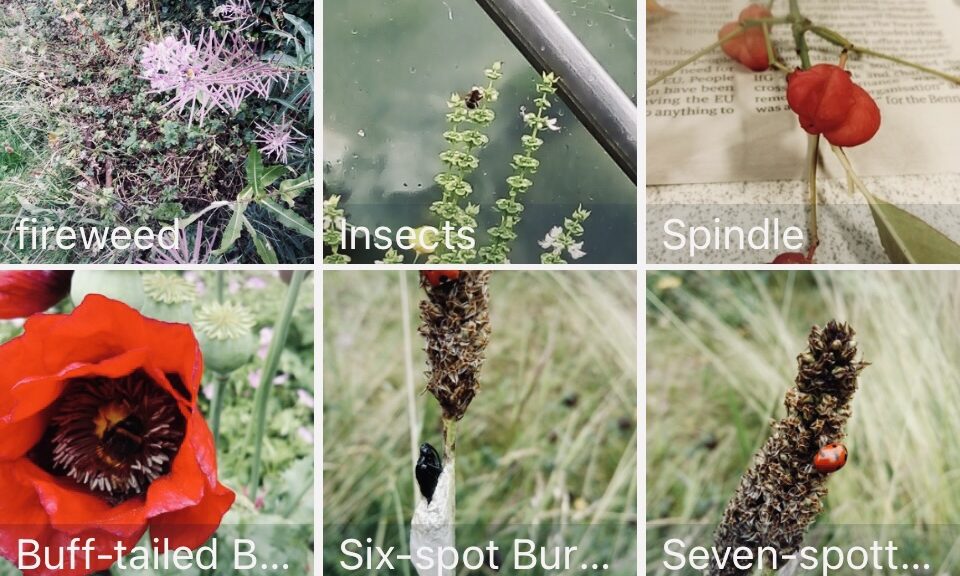

3. Gardening with the month (organic and permaculture techniques companion planting, vagabond plants, pollination)

4. Recipe for the season

5. Garden Goodness (herbal remedies and garden wellbeing)

6. Correspondences (imaginative pieces inspired by garden animals)

Illustrated with photographs, drawings and patterns created by the volunteers, the Almanac serves as both a legacy project to enhance the visibility of The Comfrey Project and a practical ecological instrument grounded in diverse global experiences.

Together these chapters contribute to reimagining urban space as dynamic, living and lively ground, offering insight into how diverse cultural imaginaries can contribute to community-led, ecologically attuned, urban placemaking.

Matters of Care

This creative collaboration opens new avenues to valorize and make visible the experiences of people in the contexts of mass migration and climate change adaptation. Urban gardening and horticultural practices are vital for supporting refugees and people seeking asylum, but current research can overlook the natural environment’s role in migrants’ lives and adaptation. While there is growing awareness around the importance of diverse land knowledges, studies focusing on displaced people’s sense of place in ‘host’ countries remain scarce. A creative collaboration, The Comfrey Almanac provides a shared foundation to understand the complexities of ‘uprooted belonging’ and the role of gardens for refugees and asylum seekers in asserting their right to homemaking.

Moreover, it is hoped that this book will catalyze community-led practices to inform applied and transformative urban agendas.

Roots and Routes

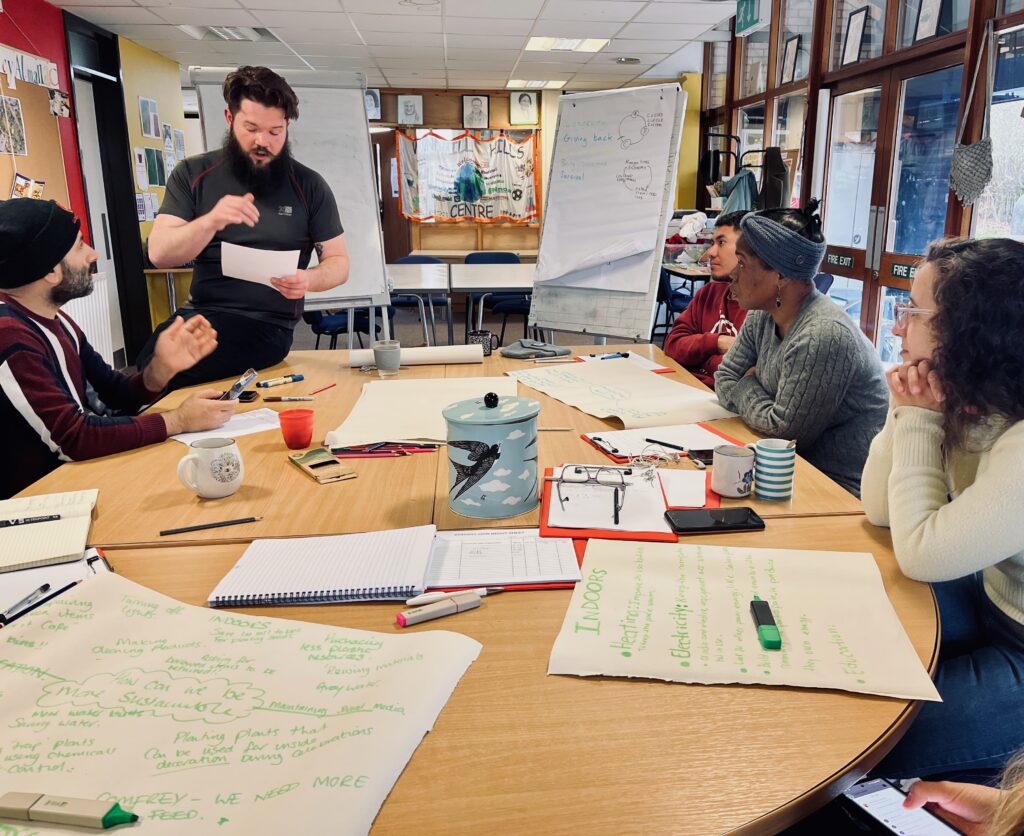

The Comfrey Almanac emerged through lots of conversations between me, staff and volunteers at The Comfrey Project and the concept was finally conceived by myself and Nicola Bushell, The Comfrey Project’s coordinator. The materials for the Almanac were collated from a series of workshops, activities, archival research and documentation. I have been involved with The Comfrey Project since 2021, assisting in organising their participation at my colleague, Dervila Cooke’s (DCU), ‘SeasonsPace’ workshop at Airfield Urban Farm in Dublin and leading the ‘Sowing Stories’ workshop at Windmill Hills with local artist Sara Cooper in July 2022. From January to July 2023, I undertook a Knowledge Exchange Sabbatical at The Comfrey Project, funded by Newcastle University. The thematic threads of the Almanac developed from enriched conversations, listening, and co-working during this time, and it was Nicola’s eureka moment: ‘Let’s do an Almanac!’ that gave the project its shape. Over my time spent at The Comfrey Project, the volunteers have revealed the garden as a sanctuary, providing relief from everyday stress and political pressures. In addition to fostering attentional care towards urban nature, gardening activities help build human social capital and a sense of empowerment through bonding, bridging, and shared decision-making. These shared insights have shaped the Almanac’s rationale, motivation, aesthetic and formal construction.

Making

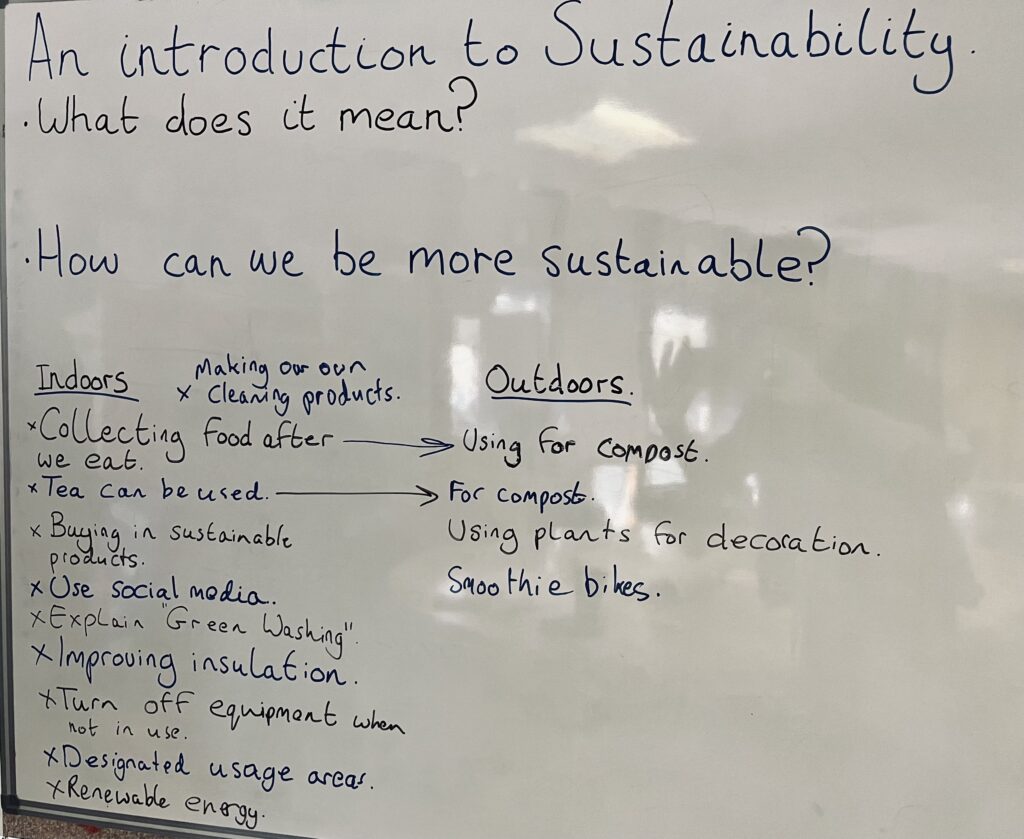

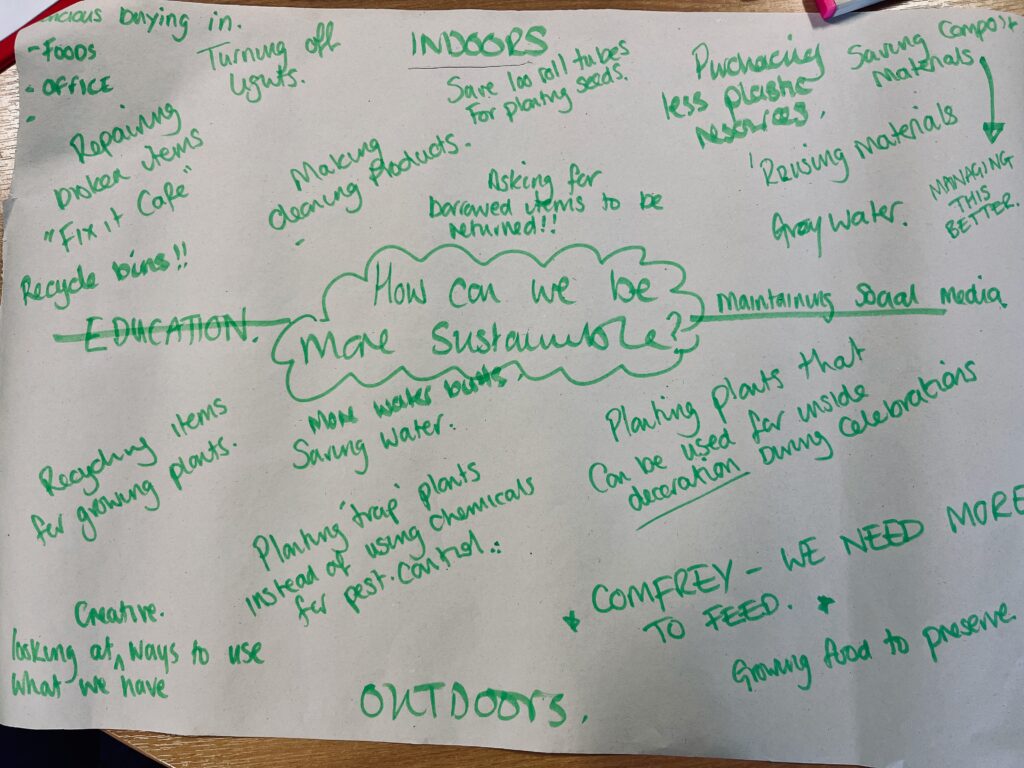

From June to August 2024, a series of artist-led workshops engaged the volunteers to produce an array of textual and visual content for The Comfrey Almanac. These workshops encouraged creativity, collective discovery and personal expression. Artist and designer Ronan Devlin led participants in crafting garden-inspired patterns through foraging, photography, embroidery and drawing. Experimental photographer Dominic Smith guided the creation of Anthotype illustrations, using sunlight to imprint organic materials and plant pigments onto photographic paper. Writer Ruth Brickland worked with both adults and children to develop narratives through conversation and creative writing, resulting in anecdotal and observational texts.

I compiled the images, objects and texts produced during these workshops to produce the materials for the Almanac. These elements were interwoven with each monthly section, establishing The Comfrey Project volunteers as co-authors. The final content underwent review and refinement in collaborative sessions. In early 2025, the Almanac’s design and layout was organised into twelve monthly sections, capturing the garden’s seasonal transformations and the volunteers’ evolving engagement. This process integrated photographs, documentation, co-creative mapping and poetry from the 2024 workshops and from previous sessions.

Each spread was then designed with care by artist Ronan Devlin before going to print.

Scaffolds

This project was made possible by the generous support of individual donors, Newcastle University’s Humanities Institute, The Centre for Researching Cities, the North East Combined Authority and the Economic and Social Research Council.

Special thanks to the crowdfunding contributors: Penny Schofield, Rachael Brien, Jeremy Hofmeister Mac Lynn, Heart & Parcel, Ashley Shield, Lily Kroese, Alison Bray, Mary McGrory, Ailsa Rutter OBE, Helen Raffle, Conor Clarke, and Peter Jackson.

At Newcastle University, we thank the NU Humanities Research Institute, the Centre for Researching Cities, and the Economic and Social Research Council funding team. We also thank the North East Combined Authority for their enthusiastic support.