Introduction

Imagine: it is 23 July 1973. You are standing at the bottom of a stone staircase that leads to a museum. Out of the entrance strolls a woman carrying a bucket and a mop. She stops, tips the bucket of water and starts to scrub the stone steps one at a time.

This scene is the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles performing her art piece Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. Ukeles, a feminist performance artist whose work is themed around maintenance and service work, was the first artist-in-residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation.1 Before this residency and her performance at the art museum, she produced her radical Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, an indictment born out of frustration with the art world’s failure to engage with the routine labour of everyday life, including the toils of (her) motherhood.2 In her subsequent work with the New York Department of Sanitation, Ukeles expanded this idea of maintenance labour beyond the domestic to the many essential, yet overlooked, maintenance jobs in wider society.

In her manifesto Ukeles argues that the world is split into a ‘development system’ and a ‘maintenance system.’ Ukeles considers the maintenance system ‘the life instinct’ with its aim to ‘preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress’ or, to put it in more simple terms, to keep things going. The development system – the creation of things – is ‘the death instinct’, according to Ukeles, a drive that focuses on ‘pure individual creation; the new; change; progress.’ Within this stark opposition, the maintenance system carries less social status: maintenance is seen as repetitive, boring, and endless or, as Ukeles puts it, ‘a drag.’ The development system on the other hand is ‘excitement!’ Ukeles poignantly summarises the dynamic between these two systems as follows: ‘After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?’3

Ukeles’ Manifesto – OHD_PPR_0003

I first came across Ukeles’ work in 2015 during my BA Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. Years later I was reminded of her work in a blog post by Charlie Morgan, an oral history archivist at the British Library. In his blog post Morgan discusses various issues arising from the large number of recordings being made during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Morgan’s main concern was the emotional consequences of recording oral history during this turbulent period, arguing that oral history interviews should not be used as a form of therapy and objecting to oral history being used to document traumatic experiences. He draws on Ukeles’ framework of a development and maintenance system to call for a better understanding of ‘the “work” of oral history’ up to and including what happens when the recording is finished. Morgan adapts Ukeles’ pivotal question when he substitutes ‘revolution’ with ‘interview’ to wonder who picks up the garbage ‘after the interview?’4

‘After the interview’

What happens after the interview is the focus of this research project. The initial aim of my proposal was to explore methods to encourage visitors of heritage sites to reuse oral history.5 My specific case study was the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall, an eighteenth century country house near the north-eastern coast of England. It was acquired by the National Trust, Europe’s biggest conservation charity, in 2009 after a large fundraising campaign by the local community.6 Designing solutions to improve the reuse of oral history proved a confusing challenge. At first glance, the assignment may appear relatively straightforward, but closer inspection soon showed that it was based on preconceptions, paradoxes, and contradictions. In his paper, ‘Three Dimensions and More: Oral History Beyond the Paradoxes of Method,’ Michael Frisch, in 2008 described the reuse – or lack thereof – of oral histories as ‘the Deep Dark Secret of oral history,’ since ‘nobody spends much time listening to or watching recorded and collected interview documents.’7

Nearly two decades ago, Frisch identified three paradoxes of oral history: ‘the paradox of orality,’ ‘the paradox of searching,’ and ‘the paradox of method.’8 In 2025, some of his perceived paradoxes have become less pressing and others more so. Frisch’s ‘paradox of orality’, for example, includes oral historians’ habit of using transcripts rather than the original audio recording.9 The transcripts versus audio is a longstanding debate within oral history, with Raphael Samuel commenting on it as early as 1972 in his paper, ‘Perils of the Transcript.’10 However, since 2008 using audio has not only become easier but also more common due to a wider cultural shift towards audio and visual media through the development of video-based social media such as Instagram, Snapchat, and Tiktok, and the rise of the video podcast on YouTube. On the other hand, Frisch’s ‘paradox of searching’ – how ‘contemporary search tools are producing a significant decline in research skills’ –11 has only become more acute over the decades. Advancing digital technologies, including Generative Artificial Intelligence, now possess the ability to transcribe, search, and summarise audio far beyond the capabilities of the search engines Frisch originally examined. Nevertheless, Frisch (among others) was convinced that the key to increasing oral history reuse, despite these paradoxes, lay in the right application of cutting edge technologies available at the time.12 Yet, as I will argue below, the projects which sought to improve reuse through new technologies, consistently failed to recognise the crucial role of ‘the drag’ maintenance.

Frisch’s third paradox, the ‘paradox of method’, includes the persistent focus on producing rather than reusing oral histories, which he declares as peculiar given the majority of historical methods centre around studying primary and secondary sources, not the production of sources.13 The drive to add to existing archives hardly comes as a surprise since oral history as a discipline sprung from a need to diversify the archive. The archive as a neutral and reliable record of historical facts needed both questioning and actively counteracting by adding overlooked voices, groups, positions. In some regions this involved adding the voices of the original population, such as in South America, Australasia, and North America. The historiographical narrative suggests that in Europe the focus for recording was more on non-elite groups, such as the working class and women.14 The preoccupation with recording is almost universal and is evident in UK organisations, including National Life Stories, the charity embedded within the oral history department of the British Library. The charity states that, ‘its key focus and expertise has been oral history fieldwork and for thirty years it has initiated a series of innovative interviewing programmes.’15

In addition to a fixation with recording, Joanna Bornat in her work on archived oral history data identified a ‘discomfort’ around reuse. She attributes this, in part, to oral history’s connection with the social sciences where it is common practice to destroy data sooner than archiving for future use.16 However, the focus on recording and a discomfort with reuse does not mean there is no reuse at all. Beyond academic practices, there is a clear appetite for forgotten voices and stories, leading to increasing numbers of historical book series that unproblematically draw on oral histories from a variety of different archives.17 Furthermore, it is argued that the academy’s turn to memory heightened interest in people’s personal memories, making archived oral histories a central source of study.18

In spite of easier access and a general increase in reuse, adding new recorded material is still the preferred activity. The focus on ‘what happens after’, – digital hygiene, data protection, storage and accessibility issues, in other words, maintenance – is still regarded as the less significant activity. Yet access is a prerequisite for reuse. Many recordings produced by National Lottery funded projects, for example, are remarkably difficult to find.19 Throughout my project, when I asked oral historians where their collected oral histories were stored, I was often met with guilty mumblings as they admitted the recordings were gathering dust on a private hard drive. Most significantly perhaps, at the time of writing, the British Library sound collections remain inaccessible due to a cyber-attack which took place in October 2023.20 This is however not an issue of reuse, but an issue of access.

The initial idea of my project was built on the assumption that access to oral history was stable and consistent, and that I could concentrate on optimising the reuse of oral history. However, I soon realised that the period ‘after the interview’ should stretch to cover thinking about reuse and maintenance. The latter currently largely escapes the consideration of oral historians – myself included, at least initially – because maintenance is taken for granted. This insight, combined with the re-acquaintance with the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, led me to change the focus of my research: from stimulating reuse to maintaining good quality access to oral histories.

Impact on Design

This shift in perspective led to an important change in the approach of my design process too. I now aimed to create a better understanding of how we maintain access to oral histories using design methods, rather than designing something clever and new to encourage greater reuse. Christopher Frayling in his seminal paper, ‘Research in Art and Design,’ discusses three ways in which design relates to research. Based on the work of Herbert Read he distinguishes: research into design; research through design; and research for design. Research by practice projects such as the one in hand, according to Frayling, should be led by the principles of research through design (RtD). Broadly speaking RtD covers material research, development work, and action research.21 The latter, action research or AR, is the central methodology for my project. The central tenets of AR are practical research and contextualisation aimed at communication through a portfolio and a report. Communication through ‘the activities of art, craft or design’ is key.22

My AR took the form of three shorter research placements and a three-year oral history project. The longer running oral history project took place at Seaton Delaval Hall, a National Trust country house in Northumberland. The three placements were at the archives of the National Centre for Biological Studies (Archives at NCBS) in Bengaluru, India; at the British Library in London; and with Seaton Delaval Hall, the same location as my oral history project. The three research placements and the longer oral history project provided the opportunity to include the staff and volunteers at the various institutions as ‘active participants’ in my work.23 As active participants, they were the ones leading the conversation, while I took on the role of ‘friendly outsider’ who asked questions with the support of explanatory and exploratory design artefacts.24 These artefacts varied from flowcharts to short animations to mock-ups of permission forms. They stimulated dialogue by either presenting the existing situation in a novel way or by developing alternative futures through open and often playful exchanges. The conversations with the active participants allowed everybody involved, including myself, to lay bare and explore the invisible and taken for granted aspects of maintenance as well as to identify opportunities for delicate design interventions, each in their own, specific, context.

I framed maintaining access to oral histories as a ‘wicked problem.’ A wicked problem is a staple term in design theory formally established by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in their 1973 paper, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.’ Broadly the term refers to stubborn and complex societal problems.25 Rittel and Webber position their definition of the wicked problem in opposition to the received scientific and linear perception of problems and problem solving, in which a problem is defined and demarcated before a solution is found. A wicked problem resists this linear approach and is solved only in a non-linear manner: both the problem definition and possible solutions are developed simultaneously.26 This approach is central to what RtD and AR involves: conducting a continuous conversation between the designer, the people inside the design situation, and the situation itself.27 Translated into the terms of this project, the conversations were between me and my colleagues at the placement organisations, focused on the wicked problem of maintaining access to oral histories. This non-linear way of working lent itself well for my research into maintenance: the invisibility and taken for granted nature of maintenance meant new information was continuously uncovered throughout the project, which required me to reflect again and again on my interpretation of the problem and hence on my proposed interventions.

My placements in India and London and my in-depth work at Seaton Delaval Hall and the National Trust, revealed two main culprits of the situation’s wickedness. The first is how the digital revolution has altered public expectations of access to information, including archival material. Systems that grant access to oral histories need to be adapted to ensure these new expectations of instant digital remote access are met. This is a form of maintenance known in software engineering as adaptive maintenance, where a system is updated in reaction to changes in its environment.28 The second component of wickedness is formed by the obstacles that block the required maintenance from happening: rigid organisational or hierarchical structures and, above all, limited resources.

Rittel and Webber argue that there is a ‘no stopping rule’ with wicked problems.29 There is no clear or inevitable moment at which the problem can be considered as solved. This means that the components of wickedness I identified during my research will be different from components of wickedness in the future. Because there is no clear end moment of a wicked problem, there is equally no end to the number of solutions, ‘solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad’ meaning the problem can never really truly be solved.30 The inevitable conclusion is that I cannot design something which will solve the wicked problem of oral history access and reuse ad infinitum. However, while design desires to fix the world and create new and better futures, maintenance wants to simply ensure that there is a future. Maintenance is the ‘life instinct.’31 It accepts that the same work will need to be done tomorrow and the day after. I decided to embrace Ukeles’ plea to recognise the prerequisite nature of the ‘life instinct’ and chose to design with a maintenance mindset.

With a keen eye for the unique situations of each of the placement organisations I was working with, I aimed to create outputs that allow space for adaptive maintenance despite the obstacles I had repeatedly witnessed. I have dubbed this ‘wicked maintenance’, a form of maintenance that accepts that there will always be new developments that require adaptations (the unsolvability of wicked problems), but that should not inhibit the striving for outputs that seamlessly integrate into existing systems. It is a form of maintenance-oriented design that does not chase the revolution but focuses on ‘after the revolution.’

The combination of oral history and design within one research project is uncommon. Yet it proved to be a fruitful match. With oral history as my subject I was able to understand how maintenance can function as a form of design. From oral history’s relationship with digital technology to the ethics of reuse to how it fits within pre-existing ideas of history and heritage, the wicked problem of accessing and reusing oral history underlines not only the crucial significance of maintenance, but equally how society values maintenance and the experience of maintenance labour today.

This critical commentary contributes to the fields of oral history, design, and public history and heritage, not only because it is a multidisciplinary project, but also because maintenance is a universal and essential form of labour across all disciplines. The text consists of three parts. The first part contextualises my practice within the fields of both oral history and design, with a specific focus on how maintenance addresses a gap in these respective areas. The second part describes my methods and practice. And the last part discusses my findings and outlines my contribution to knowledge. Following the practice of AR, this commentary should be read in close conjunction with my portfolio of practice.

Part One: Context

With this section I wish to position my work both within the field of oral history and design. I will do this by looking at how maintenance has been discussed in these respective fields (if at all). And where my maintenance oriented project might offer a new perspective in the conversations about oral history reuse, and sustainable and ethical design.

Oral History and Technical Failures

‘To invent the sailing ship or steamer is to invent the shipwreck.

Paul Virilio, The Original Accident, (Polity, 2007), 10.

To invent the train is to invent the rail accident of derailment.

To invent the family automobile is to produce the pile-up on the highway.’

The story of access to oral history is the story of technology. This is not because oral history would not exist without audio technology, analogue or otherwise. The written recording and use of oral testimonies in constructing biographical accounts predates audio and video recording.32 It is the story of technology because contemporary oral historians have chosen to tie their work to technology through all its iterations for multiple reasons. This should not come as a surprise. Audio technology, and now more frequently video technology, captures the ‘orality’ and ‘performance’ of oral history interviews, and the internet allows anyone to disseminate oral history to a global audience. Long gone are the days of the cassette player. While the interconnectedness of oral history and technology is not the central focus of my research, I do want to examine how the history of the technologies used to improve access to oral history reveals opportunities, assumptions, and the repetition of errors that are in part driven by an over attachment to new technologies. More significantly, I seek to expose how Ukeles’ question ‘after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?’33 still remains pertinent and how chasing the next ‘hot’ technology has left accessibility in the cold.

In his paper, ‘Messiah with the Microphone? Oral Historians, Technology, and Sound Archives,’ Rob Perks provides a history of oral historians’ adoption of recording technology, which he notes started with wax cylinders and then progressed onto more portable and cheaper options. This adoption did not happen from one day to the next but occurred gradually with the more technophile oral historians leading the way.34 The creation of sound archives also developed at different rates across the globe, with the US taking longer as there was a preference for destroying or taping over original recordings in favour of paper transcripts. This was less the case in the UK.35 It was and still is a turbulent relationship. The Mini-Disc, for example, was initially met with ‘euphoria’ due its ability to record long interviews while also being very compact. However, this joy was swiftly followed by disappointment with both oral historians and sound archivists. Mini-Discs compressed files and these could only be accessed through proprietorial software. It quickly became obsolete. In general, oral historians were quicker to adopt new technologies, while sound archivists were sceptical about the ‘long-term viability and archival reliability’ of these new digital formats. In the end however, they had no other choice than to adapt as the digital oral history recordings kept being produced.36

Once the recordings were archived another challenge arose – the issue of access and reuse. Frisch painted a rather bleak picture of oral history archives, writing, ‘oral history libraries are closer than most archivists want to admit to that shoebox of unviewed home-video cassettes.’ According to Frisch this was because, ‘the content of these collections is rarely organized, much less indexed, in any depth, and the actual audio or video is generally not searchable or browsable in any useful way.’37 Many other oral historians also framed the accessing and reusing oral histories along these lines, arguing the medium is what hinders the recordings’ usability. Within these contexts the audio and video format is continuously compared to the more searchable and index friendly medium of text (analogue and digital). During the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries oral historians started to experiment with various new technologies, including digitising analogue recordings, in an effort to make the searching of audio and video easier, and allowing remote access via the internet. The resulting solutions generally came in two types of designs: the first were personalised curated collections of oral history recordings and the second were software to help navigate oral history recordings. The former includes such projects as Project Jukebox (ca. 1988),38 VOAHA (2003),39 and Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database (1998)40 which were more comparable to well-curated digital exhibitions rather than archives.41 The latter included Interclipper (ca. 1998), software most prominently championed by Frisch,42 and Stories Matter (ca. 2005) from Concordia University.43

Most designs no longer exist or exist merely as shells of their original form. They failed for a variety of different reasons. In 2006 Doug Boyd left the Kentucky Historical Society and the original version of the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database was ‘digitally abandoned’ and thereafter hacked and dismantled. Later it was reassembled, but in Oral History and Digital Humanities Boyd explains how the database needed updating and was, at the time of writing, not compatible with certain browsers.44 After the initial development of VOAHA it was plagued with all sorts of issues such as: a system crash in 2010, key team members retiring or passing away, and support for special projects being retracted. In the end VOAHA was absorbed into the university’s main library system, losing its interactive elements.45 The final blow to the original Stories Matter was the Adobe discontinuing Flash. However, new life was breathed into the software when Concordia invested 120 000 dollars in 2022.46 Now, you can download the software from GitHub.47

The wider adoption of these designs was also a recurring problem. This is unsurprising with the digital systems designed around a specific collection. The software, however, should have seen broader adoption, yet this was not the case. For example, Gluck did not use Interclipper in the development of VOAHA, opting instead to develop her own system because Interclipper failed to supply a digital file of the entire oral history recording alongside the clips, and its database was not compatible with the internet.48 During the research period of Stories Matter students at Concordia University also tested Interclipper and found it frustrating to use, worried about information being lost, and thought it too expensive.49

The interface designs of these systems also quickly became dated. High admits this was the case with Stories Matter, before the death of Adobe Flash.50 Similarly, Project Jukebox, having moved on from the CD days, still exists, but its interface is more akin to the aesthetics of Web 1.0. However, its landing page indicates there is an update project in the works.51

Although the designs have different specific reasons for failing, I argue they have a common cause: during their development little to no attention was given to the maintenance of the technology or platform. When one creates something one also creates its decay, failures, and downfall.52 If you fail to consider the maintenance required to halt this decay it is likely to disappear. Admittedly, these projects were started in the late nineties or early two-thousands before the prominence of YouTube, Soundcloud, and the rest of the internet content boom. At the time of their development people knew little about the maintenance required to sustain digital and internet-based systems. William Scheider, who worked on Project Jukebox, concluded years later they were working on an assumption that ‘it [digital technology] would save us money and personnel in the long run.’53 This assumption and then the subsequent failures of these designs perfectly summarises the limitations of technical fixes. The infatuation with new technology can lead to a failure of planning for the period ‘after the revolution.’ Technology does not replace human labour, it creates new forms of labour. And labour is essential to sustaining access to oral histories.

OHMS

The Oral History Meta-data Synchroniser or OHMS, a web-based software developed by Doug Boyd after his work on the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database,54 is a successful example of technology being used to improve the reuse of oral history. It links up a transcript and keywords to a recording, allowing the user to navigate the recording by searching the text. OHMS does not attempt to replace all human labour and instead relies on the text and the keywords to be manually inputted – most often students.55 And unlike the designs discussed above, OHMS has endured, successfully avoiding the mistakes of its predecessors.

OHMS’ success can be attributed to a multitude of reasons. However, what is especially evident is Boyd’s commitment to sustain OHMS. He learnt from his mistakes with the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, noting how grant funding allows for creation but not necessarily maintenance.56 Since its initial creation in 2009 Boyd has continued to work on the maintainability of OHMS. In 2023 OHMS was added to the Aviary platform. This move made it easier for OHMS to be used outside of the US as Aviary’s expertise can help make it compliant with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Later in 2025 additional features will be rolled out to help it better integrate into the new era of AI.57

Despite Boyd’s extensive work on the maintainability of OHMS, he cannot guarantee sustained access to oral histories. OHMS is only one component of a broader system that enables access. Access to oral histories is only solidified if every element of this system is maintained. My project aimed to identify these individual components and explore how they are maintained.

At this point in time oral historians risk repeating the errors of the past. When the Oral History Association held a virtual symposium with the theme ‘AI in OH’ in July 2024,58 the programme failed to address sustainability or maintenance, and only two of the ten sessions touched upon the ethics of AI with the rest focusing on AI’s role in improving the access to oral history, echoing the claims made by those who championed digital technologies in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and their belief that technology would address existing access challenges.59 My research offers a new perspective to this current conversation around the intersection of digital technology and oral history.

Design and Wicked Problems

Design is a nebulous concept, encompassing diverse forms, applications, and philosophies.60 This makes it a challenge to position this project within the field of design. The first issue arises when trying to find design literature that discusses maintenance. Maintenance, the capacity of repair, and general sustainability have been written about, however the majority, if not all, of this existing literature is based around product design or physical infrastructures.61 These texts are not directly applicable to my project as I am not designing a product for production. In fact, if we take the perspective Ukeles offers in her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, then maintenance and design seem to stand in opposition to one another.62 Design, including those who do follow sustainable or eco-design, are focused on production and development. Nonetheless, I believe there are parts of design theory, specifically those oriented around Rittel and Webber’s idea of wicked problems that can be applied in a manner to help designers consider maintenance even if the original text does not explicitly mention maintenance. In the following section I use certain design theories and methods to configure a form of design appropriate for this project, where I am aiming to develop a better understanding of maintaining access to oral histories.

Design does not have clear-cut origins. For many decades design existed across the arts and the sciences.63 As Lucy Kimbell writes, the version of design born out of art schools is generally considered to be occupied by ‘form’ – following Chrisopher Alexander’s idea that ‘the ultimate object of design is form.’64 Although even here there are discrepancies if one considers art movements such as Bauhaus where function informed form. The scientific orientation of design came from Herbert Simon, a political scientist, who wrote, The Science of the Artificial in 1969 and ‘suggests that designers’ work is abstract; their job is to create a desired state of affairs.’65 My project fits within this latter orientation of design, however many designers, myself included, no longer follow the ‘positivist and empiricist view of design as a science’ Simon writes of in his book.66 Many theorists still acknowledge Simon’s contribution to design theory, such as his proposition that design should work across fields in an interdisciplinary manner,67 but they disagree with Simon’s approach to problem solving which is based around ‘well-formed problems already extracted from situations of practice.’68 This understanding of problems ignores designs’ ability to work with ‘uncertainty, uniqueness, and conflict’ with situations.69 This rethinking of Simon’s work is the product of a change in how designers and other professionals understood problems and problem solving as subjective rather than objective. This is in all likelihood the product of a wider transition from modernism to postmodernism around the mid-twentieth century, with postmodernism generally rejecting the idea of objective knowledge. Within the field of design, the idea of problems being subjective originated from Rittel and Webber’s 1973 paper, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.’

At the time of writing their paper, Rittel and Webber noted how professionals’ abilities to solve societal problems were increasingly coming under scrutiny. Rittel and Webber define ‘professionals’ broadly, pointing at everyone from teachers to police to physicians.70 They themselves were colleagues at University of California, Berkeley; Rittel, a professor of the Science of Design, and Webber, a professor of City Planning. Again, reflecting how design’s origins are spread across a range of fields. Rittel and Webber attribute the negativity surrounding professionals’ actions at the time to a mismatch between society’s problems and the professionals’ approach to problem solving, and importantly, not their lack of knowledge.71 They theorised that the nineteenth century scientific and linear approach to problem solving, the one Simon prescribed to – define and then solve – was no longer suitable for handling the increasingly complex problems of the mid twentieth century.72

These complex problems were ‘wicked problems’ as opposed to ‘tame problems’. Tame problems are easily defined and easily solved in a linear manner and formulated as objective and scientific, requiring only limited solutions, such as those found in mathematics or the game of chess.73 Wicked problems were not ‘ethically deplorable’ as the term might suggest, but ‘“malignant” (in contrast to “benign”) or “vicious” (like a circle) or “tricky” (like a leprechaun) or “aggressive” (like a lion, in contrast to the docility of a lamb).’74 Rittel and Webber list ten properties of wicked problems, which I broadly categorise as either stating that (a) finding a solution to a wicked problem is complicated or, (b) implementing a solution to a wicked problem generates irreversible consequences.

| Finding solutions is hard | Irreversible consequences |

|---|---|

| There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem | Wicked problems have no stopping rule |

| Wicked problems do not have an enumerable (or an exhaustively describable) set of potential solutions, nor is there a well-described set of permissible operations that may be incorporated into the plan | Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad |

| Every wicked problem is essentially unique | There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem |

| Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem | Every solution to a wicked problem is a ‘one-shot operation’; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly |

| The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution | The planner has no right to be wrong |

I split these properties because over the decades since the seminal paper, two discussions have formed around these two categories. Category (a) – finding a solution is hard – led to a discussion surrounding the cognitive style of designers. While category (b) – irreversible consequences – created a debate around the ethics of design.

Nigel Cross, Donald Schön, and Kees Dorst all consider the particulars of how designers think. The cognitive style of designer’s is also known as “design thinking.” Their writing led to the idea of ‘framing,’ ‘reflection-in-action,’ and the idea that ‘problems and solutions co-evolve.’75 All three look at how designers continuously challenge assumptions and question the subjectivity of a problem’s formulation.76 Their writing generally follows category (a) a wicked problem’s properties, specifically: ‘The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution.’77

Category (b), the irreversible consequences of implementing a solution, is neatly summarised by Cameron Tonkinwise: ‘the creative act of designing is inherently destructive.’78 This echoes Rittel and Webber’s fifth property of wicked problems: ‘Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly.’79 Tonkinwise, also remixes Simon’s interpretation of design that it is not ‘the act of creating preferred situations,’ but an act which ‘destroy[s] what currently exists by replacing it with a preferable one.’80 If this is combined with the last property of wicked problems – ‘The planner has no right to be wrong’ – we are confronted with a rather daunting picture of designing.

50 Years of Wicked Problems

The destructive nature of design has been witnessed and discussed by many since the publication of ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’. The preface to Victor Papanek’s first edition of Design for the Real World, starts with ‘there are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them.’81 The book itself is full of examples of destructive, or ‘pointless’ design, with chapters titled ‘Our kleenex culture: Obsolescence and Value’ and ‘Snake oil and thalidomide: Mass Leisure and Phony Fads.’82 For a more contemporary version there is Mike Monteiro’s, Ruined by Design, which focuses on the destructive nature of design coming from Silicon Valley.83 The majority of the anger in these two books is directed at designers who place form over function, or do not consider problems as wicked problems. However, it is also the case that designers who do consider problems as wicked still neglect or are unable to accommodate the properties of category (b) – Irreversible consequences.

The lack of consideration for the properties of wicked problems that suggest irreversible consequences of solution implementation and even testing, is attributed by Julier and Kimbell to the prevailing neoliberal economic systems designers have to operate in. This economic system does not allow designers to directly address the causes of problems but instead alleviate the painful consequences.84 Rittel and Webber recognised these constraints placed on designers – ‘The planner terminates work on a wicked problem, not for reasons inherent in the “logic” of the problem. He stops for considerations that are external to the problem: he runs out of time, or money, or patience.’85 The ramification of these constraints leads to a performative form of design.86

These design methods do not originate from the configuration of design Rowe, Cross, Schön, and Dorst write about. This sprung from a form of designing, which is seen as ‘an organizational resource’ for businesses.87 This version of designing comes from such design institutions as IDEO where ‘design thinking’ is seen as having an important role in business strategy.88 It is here where Kimbell notes a discrepancy between the theory and practice of this form of design thinking, because it emphasises a need to empathise with the end user and yet in practice there is rarely any room for the necessary thorough reflection.89 This limited room for reflection is evident in how design as a process is commodified and squeezed into easy-to-digest flowcharts. This adoption of design thinking by business has somewhat flattened the ideas of Rittel and Webber’s wicked problem and other design theorists who emphasise the messy and reflective nature of design.90

“Solving” Wicked Problems

Rittel and Webber’s wicked problem, inspiring as it is, does not seem solvable. Framed as a wicked problem, the maintenance of access to oral histories may never be solved. Indeed, perhaps it would be unethical to try as ‘you may agree that it becomes morally objectionable for the planner to treat a wicked problem as though it were a tame one, or to tame a wicked problem prematurely, or to refuse to recognize the inherent wickedness of social problems.’91 Notably Rittel and Webber never offered a conclusive problem solving method of navigating the properties of wicked problems – ‘we have neither a theory that can locate societal goodness, nor one that might dispel wickedness.’92 And more than fifty years on we are still looking.

However, not all is lost, to combat this gloom Tonkinwise proposes ‘Transitional Design’ a form of ‘multi-stage practice-oriented’ design which is focused around creating transformation in a social and sustainable manner.’93 This is an attempt to move away from a closed form of problem solving and fully embrace the wicked problem’s ‘no stopping rule.’ Bailey et al., do something similar by opting to use the terms ‘situation’ and ‘opportunity’ instead of ‘problem’ and ‘solution.’94 The terms ‘problem’ and ‘solution,’ reflected in the business design flowcharts and even within the context of Rittel and Webber’s work, suggest a closed configuration of the design project leaving little room for what happens ‘after the revolution.’ Removing the bookends of problem and solution recognises that when designing for wicked problems you must consider there is a time after the designer’s work, which is what Tonkinwise is aiming for with Transitional Design.

Spencer and Bailey take this a step further in their paper, ‘Design for Complex Situations,’ where they offer up the idea that designing for Latour’s conception of ‘matters of concern’ is not a ‘problem-solving activity’ but a form of ‘research through design.’ Here the aim is not to design a solution but to use design methods to research and give insight to a particular situation.95 Once the situation has been ‘clarified and articulated’ to a certain level of satisfaction, those who are operating within the subject of the research take this knowledge forward and create their own solutions. Bailey and Spencer recognise those within the design situation are more suited to implement solutions because they have situation-specific knowledge that a designer may lack as an outsider working under a time limit.96

Research through design or RtD is one of the three intersections of research and design Frayling outlined in his paper, ‘Research in Art and Design,’ in 1993.97 The main aim of research through design is to gain knowledge of a particular situation without creating a solution, contributing to a wider research area for others to explore and add to as they see fit. By not explicitly designing a solution the wicked problem is not ‘tamed,’ instead RtD creates a better understanding of the wicked problem.

This understanding is created through a process of simultaneously developing an idea of a situation and identifying possible opportunities. This is consistent with the simultaneous problem and solution development which has become key to contemporary design and design thinking. However, the big difference is that these opportunities might not be implemented but work as a form of stimulation and probes in conversations with those situated within the design subject. These conversations in turn produce more knowledge and research. I go on to explain this in further detail in the methodology section.

Maintenance is not pervasive in design. Similar to those who attempted to solve the oral history reuse problem through technology, the field of design generally does not consider that when something is created, so is its destruction.98 Some, like Spencer and Bailey, and Tonkinwise, recognise a time after a design has been created – after the revolution – where maintenance should and will occur.99 It is here where I think my work sits. Where my work can contribute to conversation on how design can manage and respond to wicked problems.

Part Two: Practice

The subject of my research through design – the maintenance of access to oral histories – required a particular methodology due to the nature of maintenance. Maintenance is often invisible. In the second part of my critical commentary, I will outline my methodology followed by an account of how this method unfolded in practice.

The Method

During my research periodI spent many an afternoon as a volunteer guide in the basement room of Seaton Delaval Hall.100 I considered it a key part of my research method as it helped me to build up trust between me and the staff of the Hall. During all my placements at the Hall, Archives at NCBS, and the British Library I undertook a variety of odd jobs to familiarise myself with those working within the given design situation: the staff and volunteers. In Seaton Delaval Hall I set up an audio installation in the Tapestry Room,101 I designed an information poster for the archive exhibition day at NCBS,102 and I helped lift and move a wide range of things from chocolate Easter eggs to freshly printed annual reports. On the surface these are activities of a good worker and decent person, but they were an important part of my research strategy. In the following I will explain this research strategy in detail and reveal why active involvement in the everyday tasks at the Hall was necessary for my study of the maintenance of access to oral history.

My research topic – the maintenance of access to oral histories – posed a particular challenge as maintenance is invisible to both those who operate within the system and those who are outside it. In the case of the outsiders, maintenance is invisible for two reasons. First, the “output” of maintenance work cannot be measured. As Stewart Brand suggests in, How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built, ‘the measure of success in their [maintenance workers’] labors is that the result is invisible, unnoticed. Thanks to them, everything is the same as it ever was.’103 This means maintenance only becomes visible when it is absent, when the lack of activity causes the system to jar.104 Cleaning and general housework are obvious examples: if someone cleans a room every day, you will not notice the effect of their work until they stop. In addition, their work becomes invisible because the actions are often repetitive. As Star writes, the tasks which make up maintenance do not need to be ‘reinvented each time or assembled for each task.’ They are strangely passive activities which become transparent and ‘naturalised’ as part of a system and are simply taken for granted.105 The second way in which maintenance is invisible is because it is generally hidden from view. People become invisible through either the location of their work or the time at which they work. For example, domestic workers stay in private homes and commercial cleaners mainly work outside opening or ‘regular’ working hours.106

This invisible nature of maintenance had a clear impact on my choice of research strategy: I wanted to gain access to the invisible parts of maintenance. In order to map those tasks hidden from public view and to allow me to experience the maintenance tasks that have become naturalised to insiders, i.e. the staff and volunteers at Seaton Delaval Hall or Archives at NCBS, I opted for an involved research strategy: action research.

Action Research

AR has its roots in the social sciences but has become a well-established approach within research through design.107 AR is a research strategy that merges research, action, and participation.108 It was first described by Kurt Lewin in the mid-1940s when he formulated the founding principle of action research, namely that research needs to benefit society.109 This proposition repositioned the researcher from ‘a distant observer’ to someone directly involved in solving a particular ‘real-life’ issue.110 Over the years AR has evolved to become more democratic by including participation from what Greenwood and Levin refer to as ‘local people’ or local stakeholders.111 Today AR can be summarised as a process that seeks to be a democratic ‘a situated process’ where the ‘local people’ are not ‘passive recipients (subjects) of the research process’ but ‘active participants’ in the project.112

I created a situated process within each of the different organisations I undertook placements with: Seaton Delaval Hall, Archives at NCBS, and the British Library. My colleagues during these placements and my longer oral history project were the local people or active participants within the situated processes. They were ‘insiders,’ who possessed ‘everyday knowledge’ of the situation. This form of knowledge is ‘embodied in people’s actions, long histories in particular positions, and the way they reflect on them.’113 A significant portion of this knowledge takes the forms of maintenance labour that Star refers to as ‘naturalised’ or taken for granted.114 It was my ambition as the ‘friendly outsider’ to bring this invisible knowledge to light. I had to ‘reflect back to the local group things about them, including criticism of their own perspectives or habits’ through open discussion.115 These discussions were required to be opened up in a diplomatic and sensitive way, rather than ‘negatively critical or domineering,’ to build and maintain trust, hence the ‘friendly’ part of the role.116 In order to convince the staff that I was serious and committed, I volunteered at the Hall and carried out occasional odd jobs. I wanted to prove I was approachable and dedicated to the community rather than being the designer who came to observe, design, and leave.117

The discussions I had during my research period formed the foundation of what Greenwood and Levin refer to as, ‘dialectical knowledge generation.’ This method of dialectic discussion aims for both parties to understand each other’s perspectives and create an overall picture of the situation. The process kicks off with the designer proposing a thesis, which is then critiqued and questioned by local people, who might also propose a counter proposal, or vice versa.118 In the case of my research the proposed theses took the form of design artefacts.

Design Artefacts

A design artefact brings together the thoughts, feelings, and observations of the researcher and the participants together in one ‘thing.’119 Designers used artefacts or ‘things’ to navigate disciplinary differences and creative tensions present in the dialogues, and the exchanges of theses. A variety of parties are involved in these dialogues, each with their own agenda, jargon, and discipline related habits.120 The designer uses their skills as an interpreter to bring the different forms of knowledge together and to communicate across these “cultural” barriers.121 Within my work the artefacts came in two forms: explanatory and exploratory.

Explanatory artefacts summarised observations of specific situations.122 During my placements and my oral history project with Seaton Delaval Hall I produced several design artefacts in the form of spreadsheet, maps, and diagrams to explain and illustrate the situation I was working in. These artefacts helped stimulate the dialectical knowledge generation with my colleagues and encouraged them to reflect on their own environment and ‘naturalised’ parts of their surrounding structure and behaviour.

Exploratory artefacts were used to open ‘the dialogue between the possible and the actual.’123 They presented alternative futures or, to use Simon’s phrase, ‘a desired state of affairs.’124 By using explorative design artefacts I could ask ‘counterintuitive questions’ to gain insights ‘hidden from view by assumptions and other elements in cultural training and social systems.’125 The probing of the participants with exploratory design artefacts encouraged them to question how this proposed future would function within the existing situation. They helped identify areas where change can happen, where there was more flexibility in the system.

These artefacts were often a product of ‘reflection-in-action.’ The origins of ‘reflection-in-action’ lie with Michael Polanyi’s concept of ‘tacit knowledge’ or ‘knowing-in-action’ or ‘common sense.’ In other words, knowing something without knowing why you know it, such as recognising a face or using a particular tool.126 Schön built on this idea by proposing ‘reflection-in-action’ as a divergent way of thinking when common sense falls short and our preconceived theories of a certain scenario fail to deliver and a new theory or framing of the problem is required. According to Schön, reflection on what we are doing occurs while we are doing it. He gives the example of jazz musicians, who make music according to the collective vibe created with the other musicians.127 ‘Reflection-in-action’ is also why dialectal knowledge generation does not exclusively occur between the active participants and the designer, but also between the objects and overall subject.128

Active participants are not always present in this conversation. Not all the artefacts were shared as part of the discussion between myself and my colleagues, because early versions were sometimes messy and personal artefacts, that could be misleading if read by anyone other than the creator.129 So before the artefact was shared, it needed to be refined and tailored to the person or group it is being shown to. It might also be the case that the situation changes, such as legislation or even the environment, which requires additional reflection and thought. In the case of my research this included: a pandemic, the rapid development of Generative Artificial Intelligence, a cyber-attack on the British Library, and significant storm damage to local National Trust properties including Seaton Delaval Hall.

To emphasise again the dialectical knowledge generation encouraged by these design artefacts were within the unique individual settings of the organisations I worked in.130 This manner of working followed the principle that ‘every wicked problem is essentially unique.’131 As Buchanan writes, ‘design is fundamentally concerned with the particular.’ However, he also notes how designers work on a general level by creating ‘a working hypothesis about the nature of products or the nature of the humanmade in the world.’132 My working hypothesis on how to maintain access to oral histories in a more general sense, was developed in the period between my placements and my oral history project and took the form of a ‘domain of design.’

Domain of Design

My domain of design takes the form of my portfolio of practice composed of significant design artefacts from my larger archive.133 A domain of design is a collection of individual design artefacts, each of which encapsulates various thoughts and feelings, into an annotated portfolio which compares and contrasts the artefacts and puts them in relation to existing theories and ideas.134 Similar to the outputs of action research, a ‘domain of design’ aims to inspire others with an interest in the issue – ‘the artefact or situation sets the scene for meaning-making, but doesn’t prescribe the result.’135 The domain of design pushes the audience to interpret their own situation and invites them to engage with it in a deeper and more personal manner.136 This idea is also seen in AR: ‘we [action researchers] believe in trying to offer, as skilfully as possible, the space and tools for democratic social change, but we refuse to guide such change unilaterally from our position as action researchers.’137

My integration into the community I was researching and designing for was essential and worth the voluntary shifts in Seaton Delaval Hall’s basement. I built up a trust which allowed me to gain access to those parts of a maintenance system that would otherwise have remained hidden. My AR strategy encouraged me to nurture ‘dialectical knowledge generation’ between myself, my colleagues, and the wider subject of maintaining access to oral histories through the use of design artefacts and continuous reflection. Once I had completed my work with my various collaborative partners, my design artefacts and the ensuing dialogue continued to stimulate discussions within the organisations I worked with. In the following section I will look at how AR in practice contains certain obstacles that I had to navigate. It illustrates how the environment of the organisations I was working with influenced the outputs I created. Part three of this critical commentary will discuss how the creation and analysis of my portfolio or ‘domain of design’ developed a new way of framing and understanding, maintaining access to oral history and designing with a focus on maintenance.

In Practice

One of my National Trust supervisors suggested that if a National Trust member of staff replies to an email within two weeks, that should be considered fast. My experience of working with Trust staff members over a period of four years confirms this impression. Throughout my project with Seaton Delaval Hall and by extension the National Trust, and my placements at Archives at NCBS and the British Library, I saw how those within the design situation, my active participants in the research, had multiple demands on their time. Similarly, I, the researcher, also had other responsibilities, including, as I mentioned in the previous section, other odd jobs. This is why AR in theory is different from AR in practice. Or at least, AR is different in practice when the research environment is a fully operational public, busy day-to-day, organisation.

It is important to note that there is an existing body of literature on innovating and designing within heritage sites and other public services.138 Case studies examining the challenges involved in their operations are available too.139 However, there is far less knowledge on how the day-to-day operations of heritage sites and similar organisations influence design interventions. In the following section I will discuss how the realities of AR in practice within the context of my placement organisations affected my work and outputs. I have divided these outputs into two groups. The first are designs, systems, and documents which were created from scratch. The second are artefacts, maps, and reports that aimed to either adapt or add onto an existing system. Within each of these groups, the environment I was working in, and the people I was working with, altered and affected the outcome. This should be the case with AR, however the way they affected my work was not necessarily due to their enthusiastic engagement but rather the result of a lack thereof

From Scratch

There are three categories of designs and outputs that I developed from scratch, which I explore here. One is untested and eventually abandoned prototypes for products that would encourage visitor engagement with oral history. Another is outputs from work I completed during my placements, such as the takedown policy for Archives at NCBS and my audit of the National Trust’s sound collection at the British Library. The remaining category is solely the Research Room for Seaton Delaval Hall, because it was a unique endeavour within my wider research project. These design artefacts and outputs have been grouped according to how they were influenced by my work environment and that of my colleagues.

| Category of output | Related design artefacts |

|---|---|

| Abandoned Prototypes | |

| Work | NCBS Takedown and alterations policy, OHD_RPT_0249; NCBS sensitivity check doc, OHD_RPT_0250; C1168 uncatalogued items, OHD_WRT_0276; C1168 Audit 2023, OHD_COL_0262; NT BL Report, OHD_RPT_0274; NT property recommendations for PhD placement, OHD_RPT_0263. |

| The Research Room | Research Room Donation Flowchart, OHD_DSN_0158; Research Room Acquisition Copyright form, OHD_FRM_0192; Research Room Acquisition Proposal, OHD_FRM_0193; Research Room Agreement, OHD_FRM_0194; Research Room Guide, OHD_RPT_0195; Research Room Information Sheet, OHD_WRT_0196; Research Room Index prototype, OHD_DSN_0197. |

Abandoned Prototypes

At the time the ‘ghost boxes’ came to me one afternoon early in my PhD, I was still occupied by my original research question – how to encourage visitors of heritage sites to reuse oral histories. As I wrote in my report, ‘No Man’s Land’ – ‘The basic idea behind the books and boxes is that the user of the archive will take out a book or box and have access to notes and information left behind by previous visitors.’140 They were meant to be messy and playful, and allow a community to grow around the collection, which is sometimes difficult to achieve in an archive where you have to work in silence. The ‘sound boxes’ I created during my placement at Seaton Delaval Hall, worked on a similar principle, with inside the box a speaker and on top of the box a comment book for visitors to write their responses to the oral histories being played.

Neither the ‘ghost boxes’ nor the ‘sound boxes’ made it to testing, not only because they would have required the staff at the Hall to invest significant time and effort to organise and facilitate the testing process, but also due to concerns about overpromising to the volunteers and the dedicated Hall community. I also lacked the ethical clearance to use my oral histories to test the concepts. In fact obtaining the copyright clearance for these recordings took nearly three years to finalise!141 In the end, as the focus of my research shifted, I completely abandoned these designs.142

Admittedly, this failure should not have come as a surprise as they were developed early on in the overall project, and I had not yet gained access to the wider structure these designs should operate in. As Tonkinwise wrote ‘no product is an island. Every product exists within artificial ecosystems. […] When a new product is designed, it must negotiate that ecosystem.’143 These prototypes failed to do this to the extent they could not even be tested. Once I was granted access, after I started my placement at the Hall, I realised exactly how flawed these designs were and how unlikely they were to have ever worked at the Hall.

Work

Overall, my work during my placement at Archives at NCBS and the British Library was more targeted than my work with the Hall and the Trust. These placements were more akin to internships: I was given a task and then I would complete the task.

The outputs of my work had several iterations. At Archives at NCBS there were three iterations of the takedown policy, and two of the sensitivity check.144 With every new iteration I would receive feedback from my line manager, and due to the sociable nature of the work environment at the Archives I would also regularly discuss my work with my colleagues.145 The audits of the Trust’s sound collection did not have distinct iterations, but as with the takedown policy and the sensitivity check, I had regular contact with my line manager to check whether I was on the right track.

When undertaking these tasks I felt more like a worker than a researcher. I was given a task, and I would finish the task. I felt like an insider because, unlike my abandoned prototypes, the outputs from these tasks were easily integrated into the existing systems and workflows. The takedown policy was added to the Archives’ website,146 and the oral history team at the British Library created a PhD internship for someone to develop a workflow with National Trust staff to help them obtain the missing copyright.147

The question now is whether this was AR or simply work. In isolation, this work could probably not be considered AR. However, when alongside my other design artefacts the fact that they were easily adopted reveals that improving access to oral histories and archival materials may simply be a matter of more man-power.

The Research Room at Seaton Delaval Hall

My placement at Seaton Delaval took place over three months in the summer and autumn of 2022. During this time, I was, among other things, tasked with designing the Hall’s Research Room. The Research room is meant to be:

a place for the research community of Seaton Delaval Hall to come and exchange their knowledge. It is a library / archive / study room, which grants the public access to all past, present and future research. It is a space for staff, volunteers, visitors, students, and anyone else curious about the hall’s fantastic and complicated history.148

Designing the Research Room at Seaton Delaval Hall was an ambitious project. The staff at the Hall wanted a location to hold material that could not enter the collection, due to the Trust’s restrictive collection policy,149 but was useful to the Hall’s large research community. Prior to my placement there was no existing structure at the Hall for the Research Room, so I started from scratch.

The first iteration of the Research Room considered the space in a practical manner: including questions of where stuff was going to go, and how it should be indexed.150 I started the second iteration with a design fiction to help create a more holistic idea of the processes of the Research Room.151 Design Fiction, a term coined by the science fiction writer Bruce Sterling,152 is used ‘predominantly as an object for interrogation, from which other iterations may follow, that in the end inform a design brief.’153 Since it is a tool for understanding a situation without direct interference, it proved to be a suitable design method for my particular situation because, as discussed before, testing was to be avoided.

After making the design fiction I created a series of flowcharts to understand how the materials that would populate the Research Room should be classified. These flowcharts posed questions and the answers would determine how the material needed to be handled.154 From these flowcharts I developed various permission forms.155 The forms also had a number of iterations, as I had to revise them to mimick the Trust’s existing acquisition forms, which I only gained access to after I created the first versions.156

The Research Room is an example of trying to design something that is needed and desired by ‘local people,’ but not being fully realised due to there not being enough time or the resources. This lack of time and resources applies to both my colleagues (the active participants) and myself, because I could also only dedicate three months of my time to this endeavour due to my funding body’s restrictions on placements. This is why there were gaps in the final Research Room guide because I lacked the information to fill them myself.157 In the gaps I left as much information and advice as I could, but made sure to emphasise more work had to be done.

What I learned from designing from scratch within these types of organisations is that designing takes a long time because the active participants in the AR process have other responsibilities. However, mimicking existing structures and utilising the recipient’s familiarity with certain aesthetics makes integration and adoption easier.

Adapting Systems

Throughout my research project I worked with three systems: the work culture at Archives at NCBS; the collection process at Seaton Delaval Hall; and the National Trust’s general system for managing oral history. The British Library, although it is a system on its own, I included in the latter due to the Library holding the Trust’s sound material. These systems all vary radically in size and culture, and I had different amounts of contact time with each, which is evident in the final outputs.

| Output | Related design artefacts |

|---|---|

| What is Archives at NCBS? | Miro board of the NCBS away day, OHD_WHB_0247; What is Archives at NCBS?, OHD_GRP_0261. |

| Seaton Delaval Hall’s Oral History Pilot Project | SDH oral history strategy, OHD_RPT_0296; SDH OH questionnaire, OHD_FRM_0303; Copyright and reuse forms, OHD_FRM_0226; Listening session audios, OHD_AUD_0295; Feedback from listening session, OHD_PST_0289; Receipt of deposit, OHD_RCP_0293; Collection of preinterview stuff, OHD_COL_0291; Hard drive, SDH_PP; Final copyright form, OHD_FRM_0290; Screenshot of email, OHD_SSH_0294. |

| Oral History at The National Trust: Report and Guide | The Trust: stories of a nation, OHD_WRT_0273; Oral history at the National Trust Poster, OHD_GRP_0260; NT OH report, OHD_RPT_0298; NT OH guide, OHD_DSN_0299; JAN CRIT PLAN ETC, OHD_COL_0279; NT OH workshop audio, OHD_AUD_0308. |

What is Archives at NCBS?

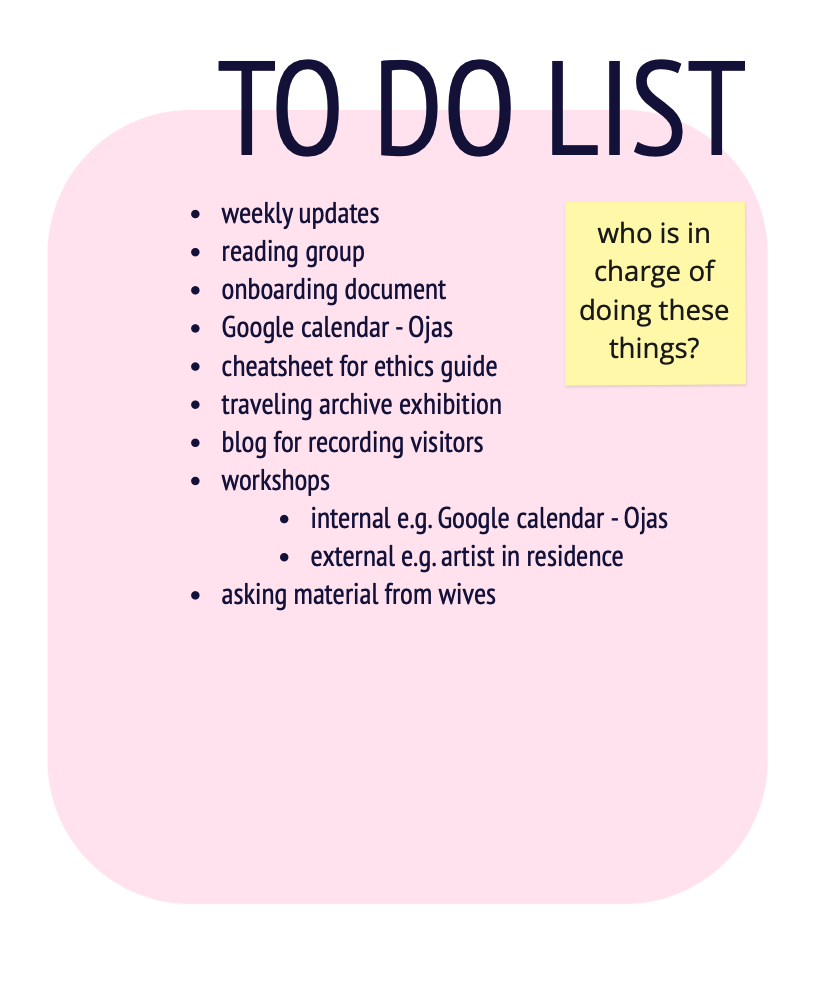

In addition to developing their takedown policy and sensitivity check I also volunteered to facilitate the Archives at NCBS staff away-day, as I was interested in researching the work culture of the Archives as part of my investigation into the maintenance of access to oral histories. During the away-day the staff partook in three activities: two were based around the aims and objectives of the Archives and one was a Stop/Start/Continue activity in relation to the Archives work environment.158 Stop/Start/Continue is a feedback activity where everyone writes down one thing they would like to stop doing, start doing, and continue doing within the workplace, and these are then shared and discussed with the group. By the end of this activity the group agreed on some actionable points. Some of which, for example the weekly updates from each staff member in the weekly meeting, were implemented the following week.

This away-day and my two months working at the Archives led me to create an infographic entitled – ‘What is Archives at NCBS?’159 The graphic explores how there are two sides to the Archives and what can be done to manage these two different identities. This concept resonated with my colleagues according to the questionnaire I sent out to get feedback on the infographic.160 However, articulating the situation cannot be equated to full implementation. It was ultimately up to the discretion of the staff at Archives at NCBS whether they adopted my suggestions.

Seaton Delaval Hall’s Oral History Pilot Project

Alongside my placements I also carried out an oral history project at Seaton Delaval Hall. Unlike the previous examples, this oral history project was not restricted to a tight time limit. Over a nearly three-year period I recorded twelve oral histories of people with varying connections to the Hall.161 Each recording was transcribed or summarised and eventually was archived at Northumberland Archives.162

The most notable part of the oral history process was the long time it took to gain the copyright clearance for my recorded oral histories. This started with me not knowing where the recordings were to be archived, because of the agreement the National Trust has with the British Library. Eventually I received permission to archive them locally instead of at the Library, which in hindsight was fortunate given the cyber-attack in October 2023. However, this meant I had to develop a copyright form specifically for this project, because the National Trust wanted to own the copyright to the recordings and Northumberland Archives also wanted to be able use the material in their exhibitions. The final form was an amalgamation of the copyright forms used by Newcastle University, Northumberland Archives, and the National Trust.163 The form was swiftly approved by Northumberland Archives, but my Trust supervisor wanted it to also be approved by the copyright staff at the Trust, so she sent them an email. Eventually they replied saying this was not their jurisdiction, because their focus is on managing the copyright the Trust already owns rather than obtaining new copyright. In the end with permission from my Trust supervisor I used the form as it was.

However, obtaining the copyright and getting people to sign the form was another issue for several reasons. Some people had changed their contact details or had not been volunteering at the Hall in the immediate period, or were simply forgetful. Luckily with the invaluable help from the Hall’s staff all the forms were signed before the day of the listening session.164

The advantage of the oral history project lasting as long as it did was that by the end the staff at the Hall were familiar with how an oral history is recorded and then prepared for archiving, making the development of the Hall’s oral history strategy significantly easier.165 By the time the final workshop I ran to develop this strategy finished, the staff felt they could easily integrate oral history into the Hall’s existing collection processes and include it in their exhibitions, despite the obstacle of the Trust IT systems.166

Oral History at the National Trust

On the Trust-wide side of my work, I held a three hour workshop where I presented my findings to Trust staff and volunteers from all over the country.167 Additionally, I wrote a report on the status of oral history at the Trust and created an updated version of the Trust’s oral history guide.168 My intention with the workshop, report, and guide was primarily to draw attention to the matter of oral history at the Trust, with the hope that along the way some of my knowledge might be helpful to a Trust member of staff or a volunteer who wishes to use oral history (or finds some cassette tapes in a cupboard somewhere).

A system is not changed overnight nor in a three-month placement, and perhaps not even over a three-year period. The impact the majority of my outputs had likely extends no further than conversations, however this is not uncommon for AR projects as, ‘a central tenet of AR in general is the conversion of people who would be research subjects in conventional research into coresearchers.’169 The outputs I created turned my colleagues into co-researchers who can continue to explore the wicked problem of maintaining access to oral histories within their unique situation after I finished my placements.

Swimming through Treacle

One of my final research presentations was titled, ‘Swimming through Treacle.’170 The title came from one of my National Trust supervisors, who said getting anything done in the Trust is comparable to “swimming through treacle.” In some cases, it was like swimming through treacle, and it was frustrating. However, I do not believe it weakened my AR, but made it evolve. This is again not unknown in the field of AR as Greenwood and Levin note how the project might start off in a more ‘conventional manner’ but moves into ‘more experimental and risky forms of participation.’171 This is reflected in my outputs as the abandoned prototypes made near the beginning of my research period are a conventional form of design,172 and the final outputs for the Hall and the wider Trust are far more open and nebulous.

This section contained examples of a designer’s work with the particular. In next and the last part of my critical commentary I reflect on my domain of design. My domain of design, which takes the shape of a portfolio of practice, presents my contribution to knowledge on a general level. It displays my ‘working hypothesis’ on how we maintain access to oral histories.173

Part Three: The Reflection

In producing this portfolio, I brought together all of my research, design artefacts, notes, and miscellaneous items. It was a reflective and illuminating process. Themes, ideas, and concepts started to emerge when I grouped the individual materials together. This final section lays out my interpretation of this collective body of work. The first half looks closely at how my portfolio and research offers a particular understanding of oral history access and reuse, which has been missing from the mainstream oral history conversation. The second half looks at what my findings contribute to the discussion in the field of design around finding solutions or opportunities within wicked problems. Specifically, it unpacks how maintenance can navigate the properties of wicked problems, and how it is the task of the designer to create spaces for this to take place.

Maintaining Access

AI art generated using the prompt “maintenance” – OHD_IMG_0312

In the public domain maintenance is often stereotyped as an activity involving hardhats and screwdrivers. Specialist literature reveals a more nuanced picture covering the maintenance of buildings and physical infrastructures174 as well as digital systems and domestic labour thus adding computer code and floor mops to the picture.175 In spite of a broader scope, however, maintenance is often approached in a narrow way: it is either regarded as a technical issue – often inviting dense specialist language – or it focuses on social issues, in particular on inequalities faced by female and/or immigrant domestic workers and home makers. Similarly, the writing that discusses the maintenance of archives or heritage sites in particular focuses on either the technical aspect of archival maintenance,176 or the lack of socio-economic status of archivists as maintainers.177 In general these two framings of maintenance are rarely discussed together, however through my practice, especially my placements at Seaton Delaval Hall, Archives at NCBS, and The British Library, I witnessed how, when these two frames are combined, something more complex, more wicked, and more thought-provoking emerges.

When I sought a clear and effective way to articulate my research findings, the fragmented understanding of maintenance and the general wicked problem I was addressing, posed a significant challenge. Like a wicked problem, I initially saw no clear starting point. However, once I began curating my portfolio, a central theme emerged: many of the jobs I undertook and the artefacts I created revolved around providing and maintaining access. My design for the Research Room at Seaton Delaval Hall is the foundation of a system which will grant access to the Hall’s community research.178 The takedown policy at Archives at NCBS established a pathway for the public to question online access to archival material, ensuring that the archive continuously adheres to legal and ethical guidelines.179 My copyright audit for The British Library of the National Trust’s sound collection became a starting point for obtaining copyright, which would allow the material to be made publicly accessible.180 I realised the best method to articulate my findings was to identify the subject of maintenance and then work backwards, unpacking its various dimensions: the type of maintenance required, the tasks involved, and the potential obstacles that might hinder the process. The subject of the maintenance will determine the form of the maintenance.

For example, the physical material of roads is maintained by fixing potholes. This is a visual and tangible form of maintenance many are familiar with. Maintaining the aim of a road is more complex since this transcends the hardware and moves into the domain of purpose. For instance, the aim of a road to facilitate traffic streams might no longer be fulfilled when there is an increase in vehicles due to a newly built theme park.181 An external change has led to a demand on the structure beyond its means. The structure needs to be altered in order to, once again, fulfil its original purpose of providing good traffic flow. This is what software engineers refer to as adaptive maintenance. A type of maintenance which alters and updates a structure to better fit the changes in the environment.182 This is where maintenance becomes a wicked problem, because, as the ninth property of wicked problems states, ‘the choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution.’183 For example, a good standard of traffic flow could be maintained by expanding the roads, or increasing bus routes accompanied by a campaign to encourage the use of public transport. The choice between these two options is not as simple and linear as filling in a pothole, there are more factors at play, including access to resources, funding, and public attitudes. This is what makes the subject of adaptive maintenance a wicked problem.