Tag Archives: Oral History

OHD_PPR_0012 Print out of Michael Frisch’s chapter Three Dimensions and More.

OHD_FRM_0303 SDH OH questionnaire

OHD_SPS_0310 Timeline of technologies

| Tech scandels | Tech | OHT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | TAPE system | ||

| 1983 | CD released in Europe and USA | ||

| 1991 | Project Jukebox (funded by Apple Library of Tomorrow Grant) | ||

| 1992 | Mini Disc | ||

| 1993 | Copyright Duration Directive (EU) | ||

| 1994 | Web Mail is used in CERN | Steven Spielbarg starts the SHOAH institute | |

| 1995 | |||

| 1996 | WIPO Copyright Treaty | The Internet Archive | |

| 1997 | Wi-Fi | ||

| 1998 | Digital Millennium Copyright Act (USA) [also had a big affect on the right repair] | Interclipper demostration at OHA conference | |

| 1999 | First SD card | ||

| 2000 | The Dot-com Bubble bursts | VOAHA | |

| 2001 | First iPod and iTunes ; Creative commons is founded ; The Wayback Machine goes public. | ||

| 2002 | Zoom H2 Handy Recorder | ||

| 2003 | |||

| 2004 | Vimeo ; Facebook | Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project | |

| 2005 | Youtube | ||

| 2006 | SHOAH collection moves to the University of Southern California | ||

| 2007 | iPhone ; SoundCloud | Project Jukebox collabs with Testimony Software ; Montreal Life Stories kicks off | |

| 2008 | FRISCH : First version of OHMS | ||

| 2009 | |||

| 2010 | France enacts the right to be forgotten | Crash of VOAHA | |

| 2011 | Zoom | VOAHA II ; OHMS becomes open source ; Stories Matter is released | |

| 2012 | |||

| 2013 | Edward Snowden | ||

| 2014 | European Court of Justice legally solidfies the “right to be forgotten” is a human right ; First NFT | ||

| 2015 | Australian Generations oral history project ends | ||

| 2016 | Cambridge Analytica | Tiktok | |

| 2017 | Obama Deep Fake | UOSH starts | |

| 2018 | GDPR is implimented | ||

| 2019 | |||

| 2020 | Covid-19 Pandemic | ||

| 2021 | Chat-GPT | ||

| 2022 | UOSH ends | ||

| 2023 | British Library Hack | ||

| 2024 | Europran Union adopts some right to repair rules. | OHA conference on Oral History and AI |

OHD_AUD_0308 NT OH workshop audio

OHD_RPT_0298 NT OH report

OHD_WKS_0297 SDH OH workshop

OHD_RPT_0296 SDH oral history strategy

Seaton Delaval Hall Oral History Strategy

V1

Hannah James Louwerse

1. Aim

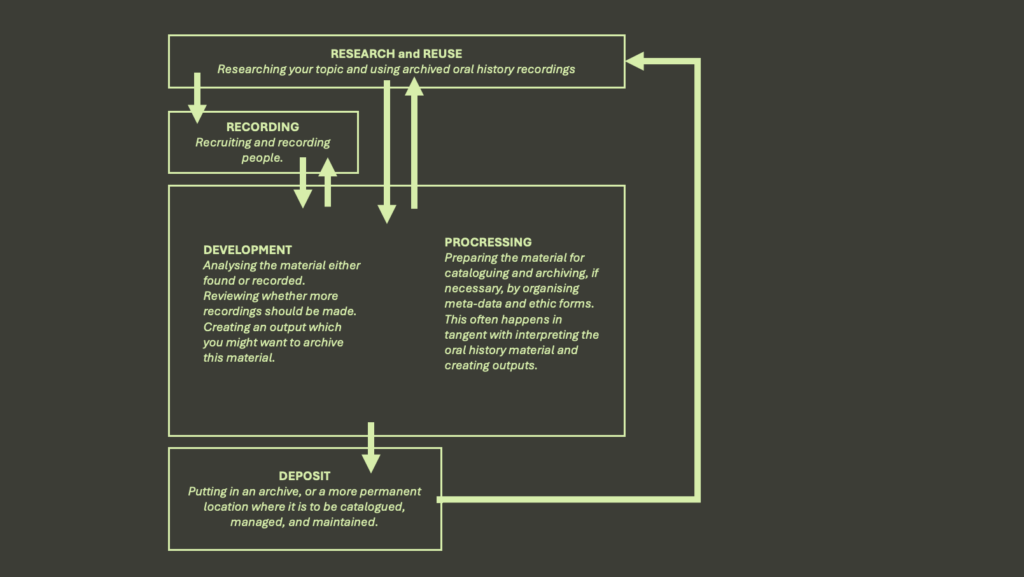

The overall aim of the strategy is to embed oral history practices into the Hall’s existing research activities to create an ongoing process of collecting, interpreting, and sharing oral histories.

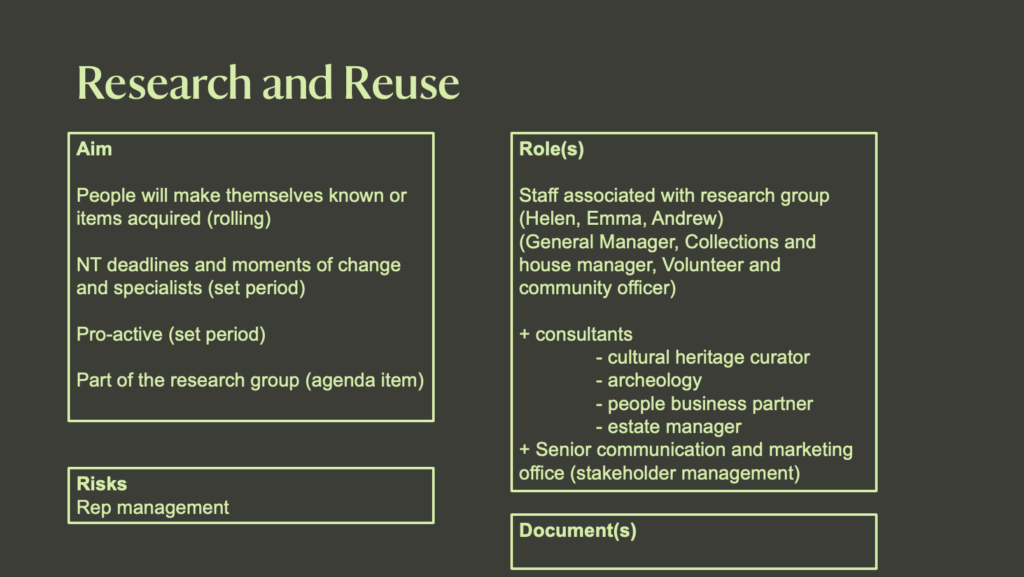

2. Roles

2.1 Core Oral History Team

The core oral history team consists of the General Manager, the Collections and House Manager, and the Volunteer and Community Officer. These members of staff already lead and support the volunteer Research Group. Their added responsibilities will encompass:

- setting up designated oral history training for volunteers and staff;

- organising the recording of new oral histories;

- recruiting volunteers for the recording and processing of oral histories;

- offering emotional support and guidance to the interviewers and transcribers.

In addition, this group will make up the reviewing team in charge of checking sensitive content in both the archived and newly recorded oral histories. They will also lead the oral history review which will take place annually during a Research Group meeting.

2.2 Supporting Site Staff

Although the Senior Communication and Marketing Officer is not part of the core oral history team, their contribution is essential for the successful implementation of the strategy. They will advise the core oral history team in matters related to the Hall’s reputation and data protection issues.

2.3 Supporting regional NT staff

Identifying and recruiting candidates for oral history interviews will require drawing on the expertise of regional National Trust staff, such as people business partners, estate managers and cultural heritage curators in, for example, archaeology.

2.4 Volunteers

Conducting interviews, managing data, and transcribing or summarising new oral histories will to a large extent be executed by NT volunteers. Equally, they will play a vital role in the researching of the archived oral history recordings.

3. Collecting oral histories

3.1 Scope and Focus

There are two forms of oral history which the Hall is aiming to collect:

- institutional memory

- histories of the cultural fabric of the Hall and the surrounding area

The recording accounts on the maintenance, restoration, and management of the site will help the Hall build an institutional memory. Collecting this information will create a collection of recordings which demonstrate the wide and diverse range of work done to preserve the site, its collection, and its history. It also avoids the loss of knowledge that occurs when an individual leaves the Hall. Histories of Seaton Delaval Hall’s cultural fabric will include recording information and stories about the collection, the hall, the gardens, and the surrounding area etc.

3.2 Pro-active Collection

The oral history is to be collected in a pro-active fashion, fully into the Hall’s knowledge gathering practices. Moments for potential collection are, for example, when a new item is acquired; as part of a research project; after restoration work; or when a significant person visits the Hall. More moments of collection will emerge as oral history gathering becomes a common practice on site.

4. Recording and processing oral histories

4.1 Training

A handful of staff and volunteers can be trained in oral history interview techniques, processing the recordings, and analysing the oral history material. Training sessions should be arranged at regular intervals, e.g., every three years. An analysis of training needs and requirements will be reviewed annually during a Research Group meeting. The training can be done through the oral history society or through Northumberland Archives.

4.2 Interim Storage

An interim storage solution needs to be arranged with the IT Department and Data Protection Office. Both have specific requirements for digital devices and Microsoft SharePoint.[1] In addition, there are restrictions on what external devices can and cannot be connected to Trust computers. Until a solution has been arranged, it is best to follow two main principles of digital storage: keep the recordings in three different locations and ensure those locations follow data protection law.

4.2.1 List of stored material

All material listed here contains personal information.

- Audio files (a WAV copy and a MP3 copy)

- Interviewee data sheets

- Recording permission forms

- Copyright and reuse forms

- Summaries and/or transcripts

- The Seaton Delaval Hall oral history catalogue

4.3 Ethics

4.3.1 Paperwork

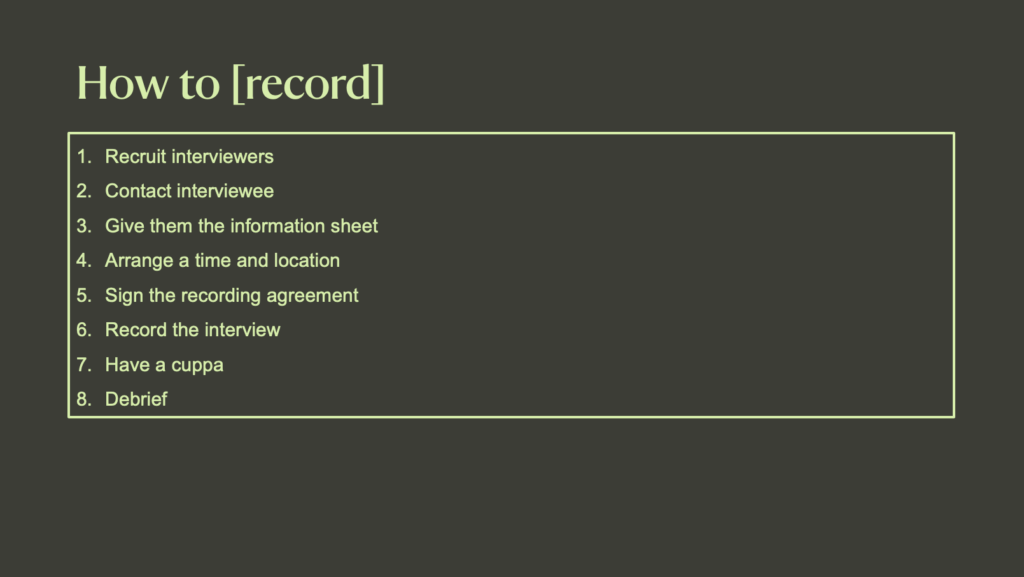

There are two ethics forms necessary to collect and archive an oral history recording:

- a Recording Permission Form

- a Copyright and Reuse Form

The Permission Form must be signed before the recording device is switched on. The Copyright and Reuse Form is signed after the interviewee has read the transcript/summary of their recording or has listening back to the audio. The Copyright and Reuse Form allows the interviewee to close all or part of the recording for a set amount of time. Note that both forms contain personal information and therefore need to be stored in adherence with data protection law.

4.3.2 Sensitivity checks

Sensitivity checks are the responsibility of the core oral history team. They will read or listen to the oral histories and assess whether there is any sensitive content. Sensitive content comes in two forms:

- information the interviewee might not want out in the public domain

- information that could upset the listener of the recording

If the former is flagged by the core oral history team because they believe the interviewee might not want to share particularly information publicly, they should mention this to the interviewee before they sign the Copyright and Reuse Form. This may result in the interviewee wanting to close a particular section of the recording. If the team finds material which fits the latter, any sensitivity warnings should be added to the index.

4.4 Indexing

The spreadsheet created for indexing the Hall’s oral history recordings allows for easy tracking of progress and searching. It is also compatible with the British Library’s method of cataloguing in case the recordings are at some point donated to the British Library. The index contains personal information and therefore needs to be stored according to data protection law.

4.5 Transcripts and Summaries

The strategic aim is to create both a transcript and a summary for each oral history recording. Transcripts are essential if the audio file is lost or is corrupted. Interview summaries allow for content to be described in more searchable terms.

5. Archiving

Oral history recordings can be archived at Northumberland Archives. However, backup copies should be kept at the Hall in case the recording is also archived at the British Library. This is especially crucial since Northumberland Archives only excepts MP3 files and the British Library requires WAV files.

6. Reusing oral histories

In connection with the Hall and the collection, oral history can be used in interpretations and exhibitions. In addition, new staff or contractors can access the hall’s institutional memory and learn about their predecessors and their work by listening to the stories shared. The overall objective is for oral history to be a fully integrated and accessible resource, equally available for consultation as any item in the collection.

[1] For example, the IT department does not want WAV files to be put on SharePoint because they are very large, while the Data Protection Office requires all personal data to be stored on SharePoint.

OHD_AUD_0295 Listening session audios

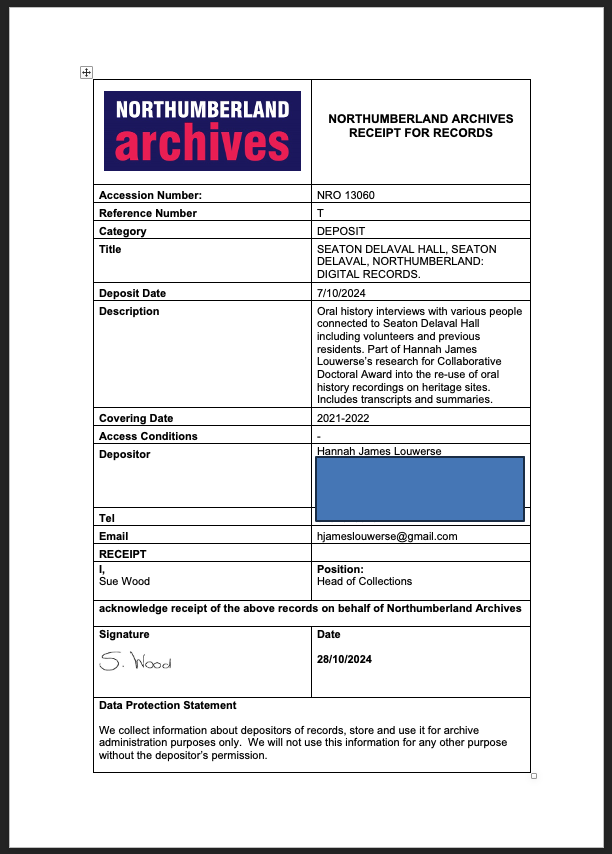

OHD_RCP_0293 Receipt of deposit

OHD_COL_0291 Collection of preinterview stuff

OHD_FRM_0290 Final copyright form

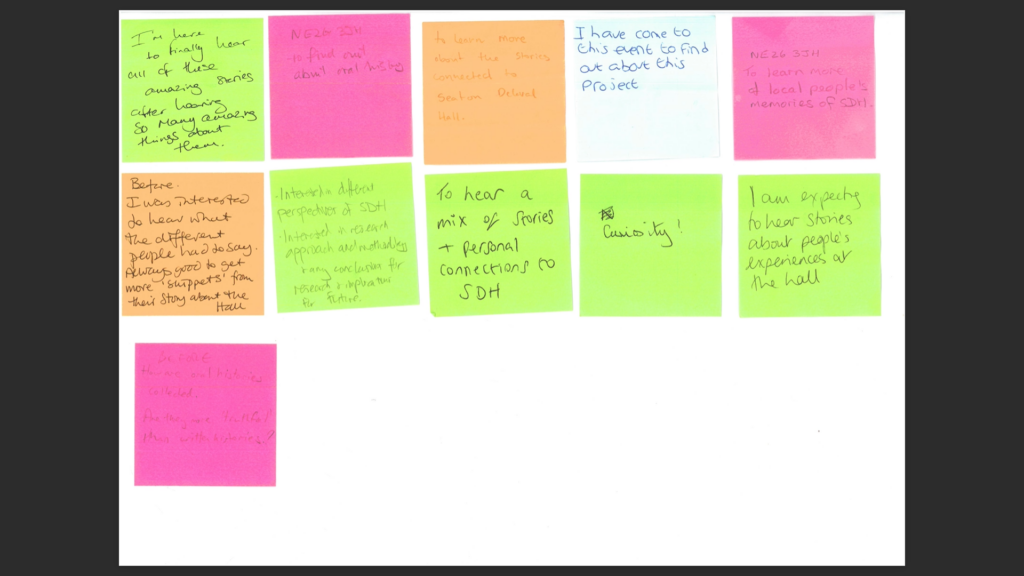

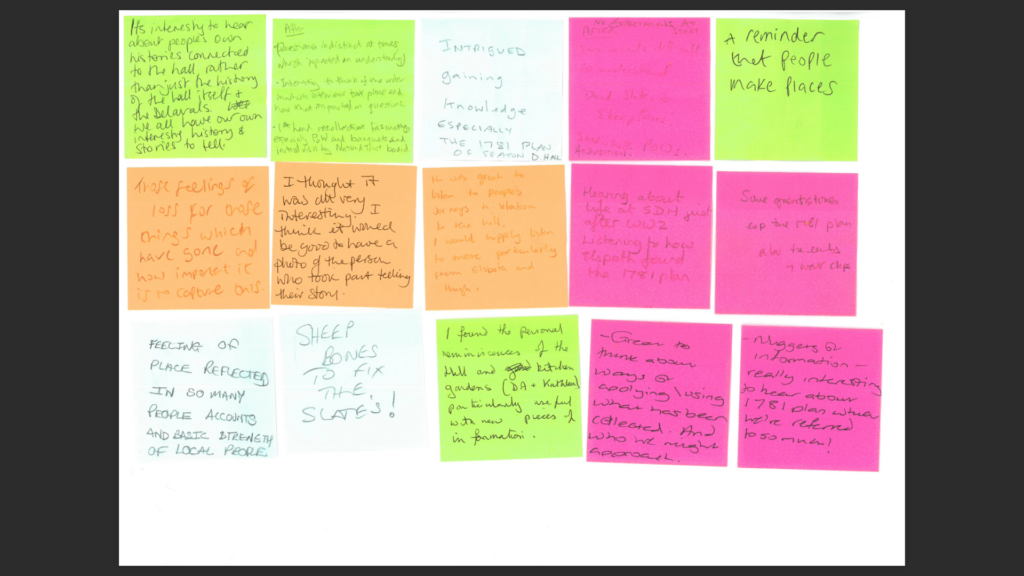

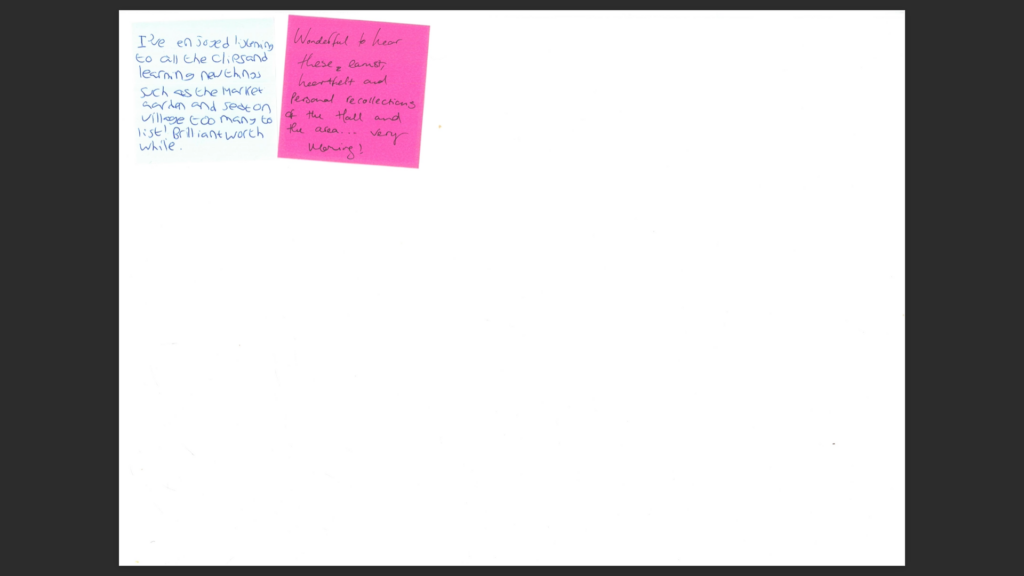

OHD_PST_0289 Feedback from listening session

OHD_COL_0279 JAN CRIT PLAN ETC

Plan for January conference/crit day – Version One

The day has been split into two halves. The first half will be more orientated towards the National Trust and any other public history institutions, while the second half is more focused on how to innovate and design solutions for maintaining archives. Both sessions will be online and will be recorded. I will also use a virtual whiteboard to document ideas, questions, and thoughts from the participants.

Morning Session – Oral history at the National Trust

Aim:

The general aim of this session to inform participants on the current status of oral history at the National Trust and to get feedback on some of my work which illustrates the various elements of oral history maintenance and see how this may translate over to the collection processes and policy at the National Trust.

Starting activity:

Everyone is asked to write down what they think oral history is.

Part one: Oral history at the National Trust up to now

In the first part of the session we will look at the current situation of oral history at the National Trust, starting with asking the group if anyone has done or has knowledge of any oral history projects done by National Trust sites. This will be followed by me giving brief history of oral history at the National Trust and information on the National Trust sound collection at The British Library. With permission from The British Library I would like to share the spreadsheet I made during my placement and get small groups to explore the catalogue for a couple minutes. We will then end this part of the morning with a quick “brain dump” where any thoughts, questions, ideas are shared with the wider group.

Part two: The future of Oral History at the National Trust

The second part of the sessions starts with me sharing my general breakdown of what is required to maintain an oral history recording. After this the larger group is split into smaller groups again and they are asked to think how this might work within the context of the National Trust. To give the groups a bit of structure they are encouraged to think of the 5 Ws and 1 H questions (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How), then think how they might answer these questions.

Ending activity:

Everyone is asked again to write down what they think oral history is.

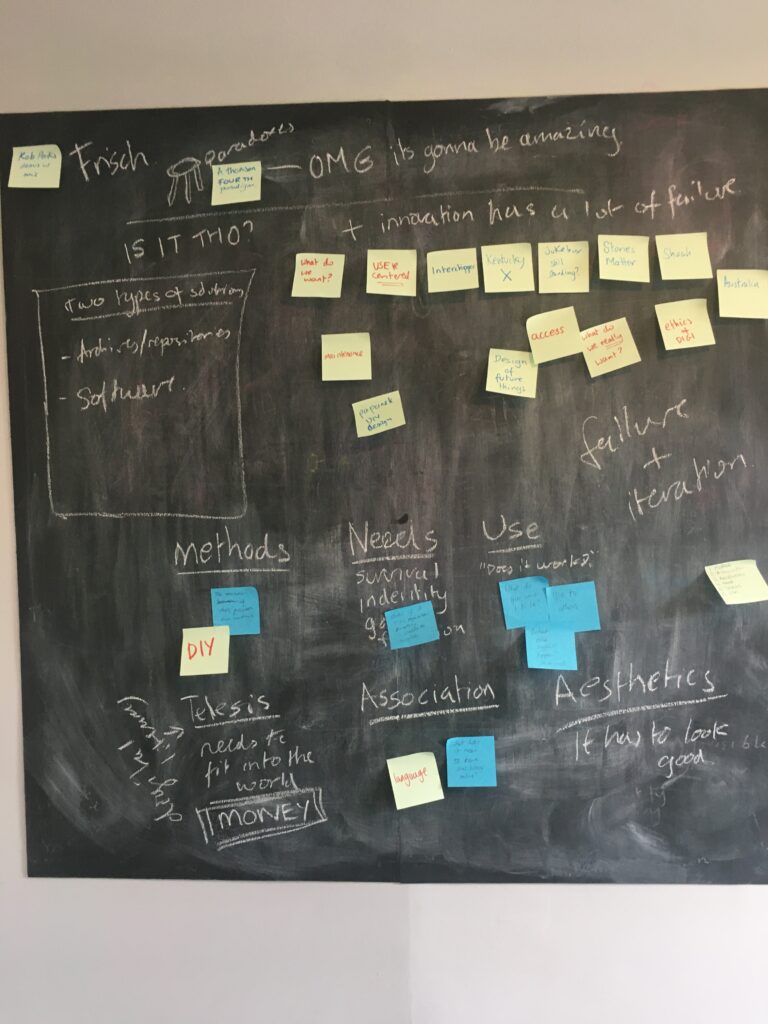

Afternoon Session – Innovation and design in archives

Aim:

The aim of this session is for me to share my experience and ideas of designing in archives.

The group will think about what it means for designers to work in archives but also what we mean by a “successful” or “good” archive.

Starting activity:

Everyone is asked to write down what they think an archive is.

Part One: What we learn from designer in archives?

In the first part of the session the participants are split into smaller groups which are a mixture between archivists and designers. Each group is given a scenario about maintaining access to oral history. They are then asked to think about what they would do in this particular scenario and as a group have to come with a plan. The plans are then shared in the larger group. They then go back into their smaller groups and are asked to think about whether the designers or archivists learnt anything from each other. After the smaller groups feedback again, I briefly talk about my experience of being a designer working in archives, specifically my thoughts on design and maintenance.

Part Two: What is a good archive?

Leading on from my thoughts on maintenance and design, the group is task with critically thinking what success looks like within archives. The group is first asked what they write what they think the value of archives is and are then given another scenario to discuss in their smaller groups. The scenario they are given is a world where everything can be kept and is accessible, all issues around digital obsolescence, copyright and data protection have been solved, but the climate crisis is threatening the stability of the storage systems, decay, and destruction of original material is inevitable. To give the groups some structure they are given a concepts and ideas matrix to sort their thoughts. After coming together as a big group again and feed backing, the whole group is asked whether the ideas and concepts they came up with reflect what they believe the value of archival material is.

Ending activity:

Everyone again writes what they think an archive is.

Version 2

Introduction to my PhD (General) – 15 mins

Story of the current collection PLUS values – 10 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

What value can oral history recordings give to the collections on sites? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

—————————————————— BREAK 5 mins

Issues with archiving and storing of OH at NT – 10 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

What resources do we need to make the flow from recording to archived easier? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

________________________________________ BREAK 5 mins

Legacy and knowledge transfer – 5 mins

Q and A – 5 mins to 10 mins

How do we make it easier to reuse oral history recordings? – 20 mins

Feedback – 10 mins

__________________________

Wrap up and thanks – 10 mins

Close

Workshop Blurb

A look into Oral History at the National Trust

Wednesday 31st Jan 2024

14:00 – 17:00

Online

This workshop is a culmination of three years of research into the past, present, and future of Oral History at the National Trust. It will take you through the stories found in the sound collection of 1700 recordings archived at The British Library, and the experience of recording Oral History on a National Trust site today. It will also offer insight into the opportunities and obstacles of recording future Oral History at the National Trust. The workshop aims to create a discourse around the rich, yet awkward resource of Oral History, how it can enrich the stories told by the National Trust, and the practical side of recording, archiving, and using such a personal artefact.

Hannah James Louwerse is completing her Collaborative Doctoral Award at Newcastle University. Her project is partnered with Seaton Delaval Hall where she has recorded oral histories from the community. She also completed a placement at The British Library auditing the National Trust’s large sound collection.

OHD_WRT_0276 C1168 uncatalogued items

Tranche 10 [G: Drive]

Property: Batemans

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – which indicates four recordings on CDs transferred from mini disc

Four PDFs – scans of permission forms, summary, transcript and additional material

Property: Mottisfont (and Stockbridge?)

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – which has 7 entries but only three are fully described. The NT reference is NT10678. There is also an additional sheet in the document for “Stockbridge” which has one entry with the NT code NT10924-001

Three word documents – summaries for interview with Derek Hill (NT reference NT10678-002), Prof. Rosalind Hill (NT10924-001, the Stockbridge one) and an BBC interview with Derek Hill (NT10678-004)

Property: Mottistone

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – single entry NT10679

Tranche 11 (Knole) [G: Drive]

Property: Knole

Folder contains:

A single spreadsheet with 73 entries

C1168 Tranche 11 [N: Drive]

Property: Knole

Folder contains:

73 folders – each folder corresponds to an entry in the spreadsheet on the G: Drive folder “Tranche 11 (Knole). Each folder generally contains consent form, interview data sheet, timed content summary and the audio recording

Tranche 12 (Southwell) [G: Drive]

Property: Southwell

Folder contains:

One folder with 95 copyright forms and a spreadsheet of oral history interview metadata with 77 entries. The difference in the total of copyright forms to spreadsheet entries is likely due to some recordings having two or more interviewees. However the reference numbers for the recordings also seem to skip between NT10985—058 and NT10985—072 which could suggest files are missing although this is complete speculation. There are two entries for Brian Kay but this seems to be a mistake and one should be Paula Clifford. For nine of the entries I had not been able to locate any files these are:

Adkin, Margaret

Bowler, David

Cotterill, L

Gaunt, William

Knobham, Lily

Pitchford Diana

Ryan, Wendy

Thomas, Doris

Wright, Frederick

C1168 Tranche 12 [N: Drive]

Property: Southwell

Folder contains:

“OneDrive_1_05-10-2020” – the interviews on ten interviewees, one has an interview summary and the other seems to have additional written material. Two only have mp3s files. None of these names are found in the spreadsheet in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive but their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

Adamson, Louise

Ball, Samantha

Grice, Irene

Hancock, Peter

Kemp, Trevor

Kent, Pauline

Manning, Michael

Nicholls, Angela

Powell, Rosemary

Williamson, Neil

“OneDrive_1_25-09-2020” – 10 tapes with summary sheets in word doc format. Lynne Bush and Dorothy Bush are the same person. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_2_25-09-2020” – 19 interviews with summaries and one extra summary sheet for Hughes, Daphne and Stanley. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_3_25-09-2020” – the audio for ten interviewees some do not have summary sheets and the is one lone summary sheet for Kay, Brian. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_4b_25-09-2020” – One interview in Mp3 format, 15 in WAV. Only six have summaries. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_5_27-09-2020” – 14 interviews no summary sheets. One additional document in PDF format. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

C1168 Tranche 13 [N: Drive]

Property: Clumber Park

Folder contains:

Material from one interview with Peter Stevenson, including permission forms, transcript and WAV file

Cupbooard

Tranche 5

Properties: A lot

Box 1 – Contains loads of CDs which are also found in the folder “C1168 Tranche 5” on N: Drive. HAS BEEN CATALOGUED but the CDs have not been given BL catalogue codes.

Box 2 – Contains CDs of recordings which are also found in the folder “C1168 Tranche 5” on N: Drive. A USB with summary sheets which are also found in the folder “Tranche 5” on G: Drive. HAS BEEN CATALOGUED but the CDs have not been given BL catalogue codes. There is also a cheat sheet explaining some stranger donations.

6 Rogue CDs – Definitely from Tranche 5 but these have bee labelled with their BL catalogue code.

Tranche 12

FIVE INTERVIEWS IN TRANCHE 12 ARE ALSO IN TRANCHE 4 IN THE FOLDER “WORKHOUSE”

The names are: Curtis & Freeman, Pointon, Smith S, Bush, Green

Property: The Workhouse, Southwell

Harddrive – OneDrive dump same as in the folder “C1168 Tranche 12” [N: Drive]

Box 1 of mini discs – Five interview which have been digitised and can be found in “OneDrive_3_25-09-2020” in N: Drive. Interview with Brain Kay which does have a summary in N: Drive but no audio file. And an interview with Margaret Adkin which does not have any material on N: Drive. One disc has no label, one has “interview (2)” as label and the final one is a test disc.

Box 2 of mini discs – One mini disc possibly labeled Touley, Law (handwriting is hard to read). And two labeled “Wendy Ryan ?” Note: Wendy Ryan’s interview is not in N: Drive.

9 CDs – also found on N: Drive. One is labeled Barker but there are two Barker in the spreadsheet

25 cassettes – Cassette not ripped from mini discs. One is labeled Holmes but there are two people called Holmes in the spreadsheet.

20 cassettes ripped from 13 mini discs

Tranche 10

Property: Bateman’s, Mottisfont, Mottistone, Stockbridge

6 cassettes of 3 interviews

A memory stick which is labeled Tranche 4 but is not Tranche 4 or any other Tranche

OHD_RPT_0274 NT BL Report

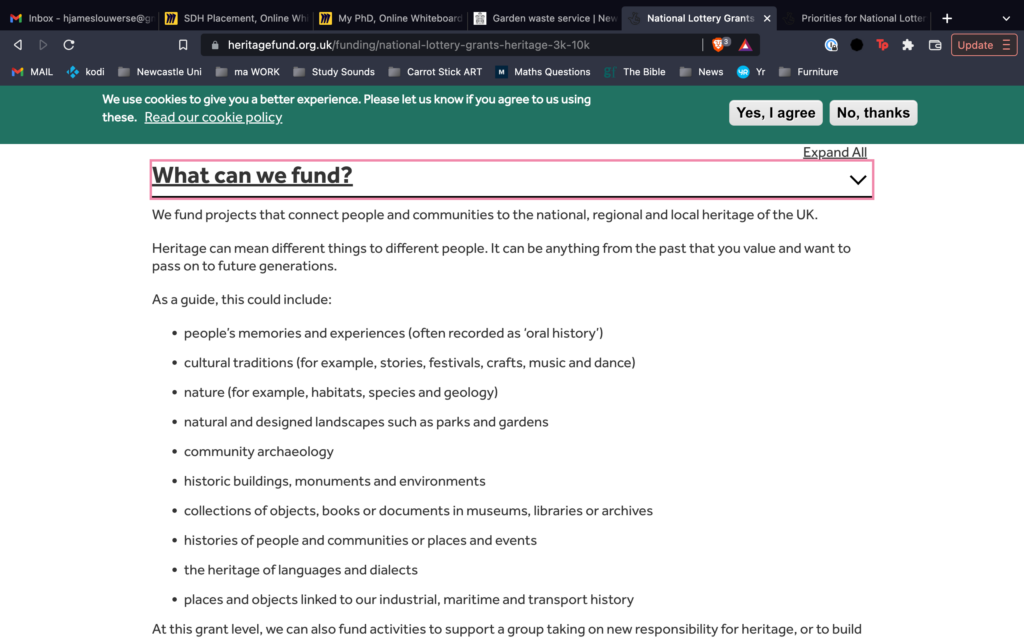

OHD_SSH_0269 Screenshot of Heritage Fund

OHD_WRT_0251 ChatGPT and oral history

E and W – Otter

0:08

The Duke of Windsor, Edward the eighth King of England for a little more than 10 months in 1936 was born at White Lodge which one sorry, on the 23rd of June at 94, son of the future Georgia the fifth and Queen Mary, great grandson of Queen Victoria and he remembers Queen Victoria, great, solemn, somewhat remote presence, queen, Empress, head of a vast international royal family.

0:37

The other Duke was born both the actuality and the idea behind the words the British Empire were at their zenith, Queen Victoria had been on the throne as long as almost anybody could remember. Her son, Edward the seventh, whom the Duke remembers with great affection not as a Monique but as an indulgent grandfather gave his name to another age, not so grand, but perhaps more golden.

1:03

So the Duke of Windsor is the last living royal contemporary of that great imperial past.

1:11

And like his father before him, the Duke went into the Navy at the age of 12. When his grandfather died in 19 110, and his father became king, he became the heir apparent. He was invested in Prince of Wales at Carnarvon, on the same spot, the same month, and much the same ring as he called it, as his great nephew Charles was last year. Then he went off to Oxford. Then came what he describes as his real education, the First World War, not so much the mud and blood of Flanders, he saw plenty of it, but the mixing with men of many different countries of many ranks and from many different backgrounds.

1:53

Now, because of the great eye opening and mind awakening which the war had been for him, he would have liked to have branched out into public work when the war was over. And as I said he did with many much fated world tours, including Canada and the United States. But his father had very limited notions of what was proper for a Prince of Wales to do. And since much of this was ceremonial and formal, the still young Prince of Wales found life somewhat frustrating. But nevertheless, in the 20s, he became more and more respected for the work he put in for the range of public interests he displayed for the nakki hand for getting on terms with people the friendly curiosity, he obviously showed in what everybody in all walks of life was doing. And because he obviously loved fun, while it was writing in steeplechase is all dancing to a jazz band, he became more and more popular, the notion grew that this prince was somehow the people’s prince, and the more so since though he kept up a tremendous round of visits in their salon Mala Hong Kong, the life of the court, the ceremonial side of being royal, did not seem to attract him in the least.

3:11

But on the early 30s, the pencil is being widely discussed for his interest in social problems, poverty, unemployment,

3:20

he was known to abroad businessman and industrialists together to see what can be done to get the country going again. newspapers printed photographs of his drawn face as he looked on slums in Lancashire, queues of unemployed miners in South Wales, and is a jack Ulation This is damnable something must be done about it was quoted and re quoted throughout the country. But let him deal with these matters in his own words in the programme,

3:48

and when I talked to the Duke of Windsor, I talked also to the Duchess.

3:54

The Duke first met Mrs. Wallace Warfield Simpson on a hunting weekend in 1931. And as you relate it afterwards, she had a heavy cold, and they hardly exchanged more than a few sentences. It was several years before they met again, that by the time he became king, on the 20th of January 1936, he’d fallen in love with her. He made up his mind that he wanted to share his life with her. And he resolved that if he could not marry her as kitten, he gave up the throne.

4:24

The record of his discussions with the government of the day on this subject are now part of history. After several tense, anguish days, the ultimate decision came December the 10th. The Duke sign the instrument of abdication gave up the throne for the woman he loved.

4:44

following June, he married Mrs. Wallace Warfield Simpson, who had by then obtained a divorce.

4:52

my conversation with the Duke and Duchess took place at their house in Paris and the wider Bitcoin 20 minutes by car from the centre of the city.

5:00

First, as you would hear the Duke and Duchess and I had a talk, sitting in the beautiful Salon of this handsome house, lay side by side, myself opposite. Then the Duchess left us and the Duke and I talked, moving into the library and settling down their wonderful room, high panels, lines of leather bound books, broad fireplace, roaring fire, and two of the four pugs present.

5:28

The Duke and Duchess live in this house in Paris in the week, most weekends, they go down to their middle house, 45 minutes southwest of Paris and the country at jif. Sea Rivette, they spend April, May and June in the United States, and usually a couple of weeks in Spain, and Portugal.

5:49

The Duke and Duchess are tremendously interested in young people absolutely fascinated by modern youth. So I began by asking them, now you both seen many generations of young people grow up? What do you make of young people today? I think they look like they’re having very little fun. I think they are. parents aren’t, of course. But the youngsters are.

00:08 – 05:49

The Duke of Windsor, born in 1894 as the son of future King George V and Queen Mary, remembers Queen Victoria and the grand imperial past of the British Empire. He joined the Navy at 12 and was invested as Prince of Wales in 1911. The First World War was a significant education for him as he interacted with men of different backgrounds and nationalities. In the 1920s, he became respected for his public work and was popularly known as the people’s prince. He took an interest in social problems such as poverty and unemployment and even met with businessmen and industrialists to discuss how to get the country going again. His discussions with the government on his desire to marry Mrs. Wallace Warfield Simpson and his subsequent abdication are now part of history. The Duke and Duchess live in Paris but spend their weekends at their house in the country and their summers in the United States.

05:49 – 09:05 TRANSCRIPT

So I began by asking them, now you both seen many generations of young people grow up? What do you make of young people today?

I think they look like they’re having very little fun.

I think they are. parents aren’t, of course. But the youngsters are.

Where do you think the parents tried to stop them? Now? How can they use this completely independent? mean financially independent? No, I mean, mentally independent and their actions and stuff? I don’t know about their finances. I suppose they work. But I think they’re independent, much more than we were when we were young.

But on the whole losing, it’s a good thing.

It’s I think it’s a good thing doesn’t matter. You know, it’s experience for them, isn’t it? Then I think they’ll turn around become different from normal. I don’t think they’re abnormal. Now. You shocked what you see today. I’m not a bit I’m interested in it. I like very much being in the red light in front of the drugstore, shelves. elisee this marvellous time.

You go around Paris quite a lot on your own looking at life.

Well, I’m always going someplace, and the streets are always filled with life. And so I looking at him all the time not reading a book in the car.

People you’re amused and interested to see the people going in and out of the truck, whatever you want to happen in the house.

I don’t think they’d want to direct, I think there was people I don’t know, I might see on the street that I might think be amusing to have, because the ones I know do come, but I try not to mix them up with too many of our age, because I think that suppresses them a bit. But I just think they’re very good for older people to have young people. It’s the younger people be kind enough to offer us with their presence.

What can the older people stand the younger people can do, but the general tendency of young women is close. manuscripts, for instance, what do you think of the minister?

Well, I think he said, You know what you’re getting down to?

Number two, many, but they got good underpinnings. All right.

But apart from how young people dress, and there’s a question on how young people behave.

And I have a great many young people come here, because that makes me feel young. And I tried to make him have a good time. Yeah. And I think they behave extremely well. I mean, they behave like we didn’t we, and they may dance in the hall. There. They may do little dances, I don’t know and show them to me, and we all try. I think they’ve extremely well.

You don’t have any feeling of young people somehow going downhill. And at

all the ones that we see anyway, short while ago, we’re talking about being with it. Now the Duchess and I are a little past the age of being what they call with it today. But don’t one minute. And imagine that we went with it when we were younger. In fact, I was so much with it that that was one of the big criticisms that was levelled against me by the older generation.

05:49 – 09:05 SUMMARY

In this conversation, two elderly individuals discuss their observations of young people today. They believe that young people are not having as much fun as they should be, although they themselves are interested in observing them. They also think that young people are more financially and mentally independent than they were at their age. They do not see young people as abnormal, and they think that it is good for them to gain experiences. The conversation also touches on young people’s behavior, and the elderly individuals believe that they behave well and are not going downhill. They also talk about the importance of having young people around and how it makes them feel young. The conversation ends with a reflection on how they were once criticized for being “with it” when they were younger.

09:05 – 11:37 TRANSCRIPT

Can you throw your mind back to the first time you met the Duke?

Yes, I met him at Melton Mowbray he was hunting there and I was asked to that same house but then I met him there.

Can you remember the first thing he said do or the first? Remember the last thing he said?

When you first met the do, did he strike you as being a very conventional kind of Englishman or as a very different kind of English.

He struck me as being wizard at that time.

What kinds of things now made you feel that about him?

I think he was ahead of his time. I think he had lots of bap and I think he’s very much ahead of his time. I think he wanted to establish things that were a little not ready for them. Really

perhaps not ready for it though. But they’ve never anything new came along. I was wanting to try it out.

Always. You felt that when you met him when he was Prince of Wales that he had a, a different and forward looking conception of what a Prince of Wales ought to be?

Yes, I really didn’t think so I thought he was very interested in everything was going on in the people and made a lot of trips. And I thought that was very interesting. Not only ceremonials, but to go down among the people, which to me as an American is what I’m used to people doing and I thought that was pretty clever.

But as he got into bad habits,

he has two bad habits. He has smoking which I disapprove very much. And then he has golfing which leaves me alone the radio.

When you say you disapprove of smoking, you mean any kind of smoking you objector. Yes, any kind, it’s not that perhaps he doesn’t put his cigarettes out or something like that. But

that’s a little dangerous. They slide off the ashtrays, tips, and again, car strains that are of putting it in. I think it’s dirty habit smoking.

Doctor told me the other day that it was better to smoke marijuana than to smoke ordinary tobacco. I’ve never tried marijuana, and I never intend to. So I’m going to stick to my

ordinary, and you’re going to stick to your golf.

So long as I can.

You really do enjoy it.

I’m very, very poor player, but I died very much from the exercise. What about the endless cups of tea? That about having

endless cups of tea, but not cups? Really? Soup plates? Or tea cups? This law?

Who drinks the tea? You Oh.

09:05 – 11:37 SUMMARY

The interviewee recalls her first meeting with the Duke at Melton Mowbray while he was hunting. She describes him as a forward-looking person who wanted to establish things that were not yet ready. She also mentions that he was interested in everything that was going on and made a lot of trips, which impressed her. However, she disapproved of his smoking and golfing habits. She thinks smoking is a dirty habit and dangerous, while she enjoys golf for the exercise. They also discuss the Duke’s habit of drinking tea, which she clarifies are actually served in soup plates, and she drinks the tea herself.

09:05 – 12:32 TRANSCRIPT

Can you throw your mind back to the first time you met the Duke?

Yes, I met him at Melton Mowbray he was hunting there and I was asked to that same house but then I met him there.

Can you remember the first thing he said do or the first? Remember the last thing he said?

When you first met the do, did he strike you as being a very conventional kind of Englishman or as a very different kind of English.

He struck me as being wizard at that time.

What kinds of things now made you feel that about him?

I think he was ahead of his time. I think he had lots of bap and I think he’s very much ahead of his time. I think he wanted to establish things that were a little not ready for them. Really

perhaps not ready for it though. But they’ve never anything new came along. I was wanting to try it out.

Always. You felt that when you met him when he was Prince of Wales that he had a, a different and forward looking conception of what a Prince of Wales ought to be?

Yes, I really didn’t think so I thought he was very interested in everything was going on in the people and made a lot of trips. And I thought that was very interesting. Not only ceremonials, but to go down among the people, which to me as an American is what I’m used to people doing and I thought that was pretty clever.

But as he got into bad habits,

he has two bad habits. He has smoking which I disapprove very much. And then he has golfing which leaves me alone the radio.

When you say you disapprove of smoking, you mean any kind of smoking you objector. Yes, any kind, it’s not that perhaps he doesn’t put his cigarettes out or something like that. But

that’s a little dangerous. They slide off the ashtrays, tips, and again, car strains that are of putting it in. I think it’s dirty habit smoking.

Doctor told me the other day that it was better to smoke marijuana than to smoke ordinary tobacco. I’ve never tried marijuana, and I never intend to. So I’m going to stick to my

ordinary, and you’re going to stick to your golf.

So long as I can.

You really do enjoy it.

I’m very, very poor player, but I died very much from the exercise. What about the endless cups of tea? That about having

endless cups of tea, but not cups? Really? Soup plates? Or tea cups? This law?

Who drinks the tea? You Oh. Have you got any things between you that you do disagree about that? You have strong differences of opinion about perhaps food or people? Anything?

hours,

hours? What you mean by that?

Well, I mean, I like to stay up very like I do. And I like to get up very early.

I don’t like to get up.

So we have hours with that works itself out. And then we’re a little late for things and I’m absolutely on the dark. Everybody says they know I’m gonna be the first person to arrive at the dinner party. Is

there a little bit like? You both like reading? So I,

I read all the time because I didn’t sleep I’m terrible sleeper. I don’t say that what I read is very educational. Because in the middle of the night, it’s always hard to read something very serious. So I read dozens of detective stories, mystery stories.

09:05 – 12:32 SUMMARY

The interviewee recalls the first time she met the Duke at Melton Mowbray and thought he was a “wizard” who was ahead of his time. She admired how he was interested in people and made trips to visit them. However, she disapproved of his smoking and golfing habits. She also mentions their differing sleeping habits, with her preferring to stay up late and wake up early, while he does not like waking up early. They both enjoy reading, with her reading mostly detective and mystery stories due to her trouble sleeping.

12:32 – 15:12 TRANSCRIPT

Did you ever think of having a career yourself?

Well, I was offered a very strange thing once years ago, and I wish I’d taken it up is when they first had that tubing for buildings. And I was offered to go around selling it. My mathematics weren’t quite good enough to accept that I

don’t think you really thought it might have been a good idea.

I think it would have been just like it’s on every building, every building is put up by that tubing now. But you

think that it’s quite a good thing for women to have careers?

I do. Indeed, I like to be head of an advertising agency, yourself. Because you’ve got lots of things to think up to sell a product and so forth. I’d like that very much.

You don’t think that being the head of such a business has somewhat de feminising effect on women

at all? I don’t see why should I think they have to use their femininity in business.

I think on the continent of Europe, I think they there are relatively few women go into business. But I think many more are going into business in Britain with that, right?

Oh, I think so. As you don’t you don’t think ma’am that women have suffered somewhat over the last 30 years by being too competitive with men that they’ve lost something of their essential character and charm

No, I don’t think so. Really. I know got many women in business and I don’t think they have it all.

Afternoon abdicated sir. You had two jobs and you’re in rapid succession.

I was appointed governor of the Bahamas. Occupied government has now sold for almost five years.

How did you enjoy getting out man,

I liked it very much wonderful climate interesting reward is being very rewarding. I ran a canteen to canteens there for the RAF. And when they were leaving, they were going to give me a present. So the dude knows that I’m speechless. I’m speechless in front of anything. So he’s, he had to give the secret away. He told me that he said they’re going to give you a silver box and I thought they wanted to be a surprise, but I knew that you wouldn’t be able to open your mouth when they presented it. So I warned you. And what happened? Well, I said fewer simple word.

Would you like to have gone on and added another job after that? So as I

offered my services if they were acquired and never gotten a job

I have to do to had a job this day much better much

in those days that 25 years ago.

I think he could have done something.

Why didn’t you get a job? Do you think?

Hard to say? Most of the people I think prevented me are underground. Now.

12:32 – 15:12 SUMMARY ONE

The conversation touches on various topics. When asked about having a career herself, the speaker mentions a missed opportunity to sell tubing for buildings. She also expresses an interest in heading an advertising agency, without believing that femininity should be used in business. The speaker discusses her time as governor of the Bahamas, running canteens for the RAF, and receiving a silver box as a gift. When asked if she would have liked another job after that, she says she offered her services but never got a job, possibly due to people underground preventing her.

12:32 – 15:12 SUMMARY TWO

The conversation includes the following points:

- The speaker was offered a job selling tubing for buildings, but didn’t take it due to lack of math skills.

- She thinks it’s a good thing for women to have careers, and would like to be the head of an advertising agency.

- She doesn’t think that being a successful businesswoman requires using femininity.

- There are more women going into business in Britain compared to the continent of Europe.

- The speaker enjoyed being the governor of the Bahamas and running canteens for the RAF.

- She was speechless when presented with a silver box as a gift.

- She would have liked to continue working after her governorship ended but never got a job, possibly due to people preventing her from doing so.

15:12 – 18:35 TRANSCRIPT

Talking about young people around talking about old people, older people say that the really great problem for them is loneliness.

There’s no problems. A man alone is always an empty seat at every dinner table for the extra man. But woman alone is quite a different. When she’s older, she may be terribly rich, because her husband’s died and left a lot of money. But what is she going to do? Who’s going to take her out to dinner? How much time is she going to spend sitting alone, unless she’s going to entertain a great deal. And then most of our friends are probably in the same. Probably widows too. You see, then the great man hunt has to go on to get someone to come to dinner and sit next to these people.

The Duchess is on Mrs. Buchanan, Merriman, who live to 100 years and three months, lived in Washington. She was originally from Baltimore. And somebody said, best Why don’t you move back to Baltimore? Because you could look up all your old friends. They said, look them up. You mean Tiger Mom? Is a wonderful lady.

Duchess What is the secret of keeping? looking young? No, no,

I’m not secret. I think happiness is a great see secret to how you feel and look perhaps leaving that happy

when you set me up very answer to.

Well, I’m very happy.

I didn’t ask him what part of the United States you came from that you would consider as your home Maryland,

the wealthy Maryland. Line one off it was the governor of Maryland.

I always consider myself a Southerner by marriage.

Is the one part of the United Kingdom that you feel more attached to than another

in Britain? Oh, yes, I think Sunningdale I think that’s part of Britain’s great affection poll.

Do you feel that in some ways the Americans have got something to teach the British and the British have got something to teach the Americans?

I think they both have something to teach each other radio I think

what what do you think that the British might learn from the Americans?

Movement pap.

And the what do you think the Americans might learn from the British?

How to speak nicely?

I think that a lot of American Express has crept into the English language,

of course that you speak with a bit of an American accent accent

says but I don’t know. I got it for me if

you have any regrets when you look back on your life?

Oh, about certain things. Yes, I wish it could have been different. But I mean, I’m extremely happy and naturally have had some hard times but who hasn’t? So they will just have to learn to live with that. But I have great fun.

I read a lot of fun.

15:12 – 18:35 SUMMARY

The Duchess discusses the issue of loneliness among older people, noting that it is a greater problem for women as they may have lost their spouse and have fewer options for socializing. She mentions a woman who lived to 100 years and three months and the difficulties she faced in finding companionship. The Duchess attributes her own youthful appearance to her happiness, and she considers Maryland her home in the United States. She believes that Americans and British people have something to learn from each other, with the British possibly learning movement and the Americans learning how to speak nicely. The Duchess admits to some regrets in life but overall has had great fun and enjoys reading.

18:35 – 20:58 TRANSCRIPT

I remember you were saying in your book that both you and the duke would have liked to have had children, for instance? Yes,

I think that’s great. Because then you learn so much more and so forth. Because makes you lonely. Sometimes if you’re, we, we have got a lot of friends and that helps us enormously. But people in a mag I suppose to have been into are really friends with their children. Before they used to be a sort of former relationship between parents and children. Now they’re all sort of friends with each other, not scared of each other. I think that’s awfully nice.

Now how that come about, do you think I think the parents just become very intelligent, your relationship with your father, sir. You were obviously devoted to him, and he was very good father. But what’s the kind of rapport between you that the Duchess is describing?

None at all. We were brought up very strictly my father was a great disciplinarian. And in those days, as opposed to today, there was an old adage which said, children are to be seen and not heard. Sometimes when my father admonished me for something that I’ve done, that my dad boy, you will always remember who you are. So I used to think, but now who am I? No answer.

Parents now are friends with their children’s it’s more of a friendship and a mother and father children relationship and that’s why I think it goes off it well.

In your autobiography, you wrote that you always found the Duke somehow remote, aloof, I think is the word you use something mysterious about him. Do you think it has to do with what we’re talking about? I think

it has a great deal to do with that. And I also think that he is still aloof in a way because he he decides everything voice says it to see whereas I just go ahead.

I don’t consider myself a loser

or not to me. No, I think he reconsiders i It’s out before I have time to think and I think he thinks before he speaks which is very good. Maybe it’s

sometimes when I don’t don’t agree with you.

18:35 – 20:58 SUMMARY

In this conversation, the Duchess and the interviewer discuss the issue of loneliness among older people, particularly women who may become rich widows but lack companionship. The Duchess attributes her own youthful appearance to happiness, and she considers herself a Southerner by marriage. She believes that both Americans and British people have things to learn from each other. The conversation then turns to the topic of parent-child relationships, with the Duchess suggesting that parents today are more likely to be friends with their children than in the past. The interviewer asks the Duke about his relationship with his father, which was strict and formal, and the Duchess remarks that the Duke is still somewhat aloof, although she sees this as a positive trait.

20:58 – 25:50 TRANSCRIPT

When the Duchess had gone, I followed the Duke into the library. As I walked under the Prince of Wales, his standard from St. George’s Chapel Windsor, hanging down over the hall from the balustrade of the staircase. I passed by the table, on which lies the red despatch box, bearing in gold letters, the words, the king was asked open by a king nearly 35 years ago to take out the abdication document, which had been prepared for him to sign on December the 10th 1936. When I talked to the Duke on his own, we went on rather a different range of topics on affairs of state on statesman he’d met, though we talked also as you Yeah, about personal matters, its parents his upbringing, hobbies, Steeplechasing, his golf. We began with his attitude to the duty and role of being a king. How would you see the monarchy today is as an institution?

Well, I think it’s a it’s a great, great institution, but the monarchy has to change. With the times we’ll go back to the days of my great grandmother, Queen Victoria, who changed the image of the monarchy, from the rather frivolous, dissolute times of what she described as her wicked ankles. widowhood struck her when she was comparatively young at the age of 40. And he lived at court and the atmosphere became one of mourning, and austerity, which she maintained until her death. You will recall that there were even great criticisms that she didn’t show ourselves more. She wouldn’t have shot herself because she said, people only want to see me in my great grief. My grandfather changed at all. During the nine years that he was king. He’d been the leader of, of the Society of Britain and all the gay life, which is now called the Edwardian era. It was a horse racing. He was fortunate enough to win the derby horse race three times for the grand national ones in the same year Dhabi. And he was seen a great deal around the country and was very popular. My father was always quiet a man, great king, and a great rain. But life had caught again, shall we say, became more subdued. When it came to my turn, during the last 10 months, um, that matter of days, I wasn’t going to change, a great deal. But I could see, although a great believer in tradition, great believer in the ceremonial which is part of the monarchy, that there was some outmoded ceremonials which could be dispensed with. In other words, all I wanted to do, and all I meant to do was to open the windows a little and let in some fresh air. After I left, my brother had also a great rain was a very popular Monique. I think he tended more to follow in the footsteps of our father. After his untimely death, early death, tragic death. My niece became the queen and bear in mind all the great changes that have taken place in these last two decades since the last war I think that monarchy could not possibly be in better hands than it is today.

You remember Queen Victoria at all?

Yes, very dimly. I was six years old when she died. She was always a very serious figure to be, I think that was called a shadowy figure in my recollection, is to never it. Windsor and Osborne, Balmoral.

And Edward, the seventh son, oh, yes,

I remember him much better. He was always very genial with his grandchildren. And we’d like to escape to what we used to call the big house and salary away from the parental discipline.

20:58 – 25:50 SUMMARY

The narrator follows the Duke into the library, passing by the table on which lies the red despatch box bearing the abdication document that the Duke was asked to sign in 1936. The Duke and the narrator discuss various topics such as the monarchy and the role of a king. The Duke believes that the monarchy is a great institution but needs to change with the times. He talks about the changes brought about by his great grandmother, Queen Victoria, and his grandfather, King Edward VII. He also discusses his own reign and the changes he wanted to make during his brief tenure as king. The Duke remembers Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, whom he recalls as a genial grandfather.

25:50 – 29:02 TRANSCRIPT

When you were a child that were you temperamentally a rebel, so to speak?

Yes, I would say I was. Because we were brought up very strictly, my father had been trained in the, in the Navy, where the discipline is very rigorous. And I think he had it in his mind that that was the best way to bring up his children.

Interesting said that your father, whom you describe as being very strict, was such a different character from your grandfather. He was.

My grandfather was strict too. But I see he didn’t become King until he was 16 when Victoria never allowed him to see any of the state papers, and so he became the leader of London society and the pleasant life of those days.

That was his compensation for not having that right. But

tell he was he was very good king that he, in the news, foreign politics very well.

When you look back on your youth set, do you think you got a suitable education for becoming a king?

I think for the time during that time that I was being educated, I think probably it was quite suitable. I was raised in somewhat restricted training of the Navy. I went to Oxford for two years, not being very bookish, I never got my degree, although one year was cut short, and I said that I didn’t get a degree because the wall and the wall. But the wall was very restricting to four years, all we had to concentrate on was the waging of the wall. I was then in the army. And now in retrospect, I’m sure that my great nephew, Charles, present Prince of Wales, from his days in school, he went to school in Australia. And he’s been at Cambridge for two or three years, I would think that he’s not going out into the world to do his job. Far better equipped than I was that time.

Would you describe yourself as a reforming King? When you occupied the throne?

No, no, I wouldn’t. I wanted to be an up to date King. I didn’t have that much time to

know. And you didn’t have as it were, you didn’t have political conceptions about how the country had lots

of political perception and kept them to myself. That is the tradition of the royal family.

What were the things that you wanted to change? Could you give me some examples, some examples of the ways in which you ran up against the conventions?

I didn’t have time I wasn’t there long enough. But I had in mind to change, especially to do with the with the court which after all, the court is dominated by by the king and he influences the court and gives the orders its command so to speak.

25:50 – 29:02 SUMMARY

The interviewer asks if the King was a rebel as a child, and he says he was due to his strict upbringing. They discuss the differences between the King’s father and grandfather, and the King says his education was suitable for the time, but his great nephew, the current Prince of Wales, is better equipped for the job. The King denies being a reforming king and says he kept his political perceptions to himself, as is the tradition of the royal family. He wanted to change things at the court, but didn’t have enough time to do so.

E and W – Youtube

ChatGPT_summaries_test_230222

Could you summaries in 100 words the following text: This is a first interview with Mimi Feingold Real for the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project. The interview is being conducted by Amanda Tewes on February 9, 2021. And Ms. Real joins me in this remote interview from Mill Valley, California, and I am in Walnut Creek, California. So thank you so much for meeting with me today, Mimi. 01-00:00:23 Real: Delighted. 01-00:00:25 Tewes: Starting at the very beginning: can you tell us when and where you were born? 01-00:00:30 Real: Okay, I was born in Brooklyn, New York, on May 31, 1941. 01-00:00:37 Tewes: And did you grow up in Brooklyn? 01-00:00:40 Real: I grew up in Brooklyn, I lived in Brooklyn. I didn’t leave there until I went to college. But basically, I guess right after I was born my parents were living in an apartment, but they moved within the first couple of years to the house that I grew up in. I hesitated at the word house, because it was what in San Francisco would be called a pair of flats, and that isn’t the term that was used. There was a two-family house, so we occupied the upstairs, and the owner of the building occupied downstairs. But yes, that is where I grew up. 01-00:01:32 Tewes: That is really interesting, the regional difference between the housing styles. 01-00:01:33 Real: Yes, yes. 01-00:01:35 Tewes: Can you tell me a little bit more about what it was like growing up in Brooklyn in the forties and fifties? 01-00:01:43 Real: Well, on one level it was very ordinary. This was a fairly residential neighborhood, tree-lined streets. We could play maybe not out in the middle of the street, but play on the sidewalk, sometimes even in the street. It was primarily a middle-class neighborhood, and in those days we weren’t even aware of these things, but it was predominantly white. And also, more important to my identification, it was predominantly Jewish—as was a good deal of Brooklyn and a good deal of New York in those days. But again, it was just something that you breathed in with the air. You went to the little shopping neighborhood nearby, and on practically every street there was a Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 2 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California kosher butcher, and there was a Jewish delicatessen every couple of blocks. There were elements of a much smaller city. We didn’t feel like we were part of some great, big, huge urban sprawl with all kinds of problems

This is a transcript of an interview between Mimi Feingold Real and Amanda Tewes for the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project. Real was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1941, and grew up in a middle-class, predominantly Jewish neighborhood. She lived in a two-family house where her family occupied the upstairs, and the owner of the building occupied the downstairs. Real shares her experience of growing up in Brooklyn in the forties and fifties, where it was an ordinary and residential neighborhood with tree-lined streets, and every street had a kosher butcher and a Jewish delicatessen.

Could you summaries in 200 words the following text: s: This is a first interview with Mimi Feingold Real for the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project. The interview is being conducted by Amanda Tewes on February 9, 2021. And Ms. Real joins me in this remote interview from Mill Valley, California, and I am in Walnut Creek, California. So thank you so much for meeting with me today, Mimi. 01-00:00:23 Real: Delighted. 01-00:00:25 Tewes: Starting at the very beginning: can you tell us when and where you were born? 01-00:00:30 Real: Okay, I was born in Brooklyn, New York, on May 31, 1941. 01-00:00:37 Tewes: And did you grow up in Brooklyn? 01-00:00:40 Real: I grew up in Brooklyn, I lived in Brooklyn. I didn’t leave there until I went to college. But basically, I guess right after I was born my parents were living in an apartment, but they moved within the first couple of years to the house that I grew up in. I hesitated at the word house, because it was what in San Francisco would be called a pair of flats, and that isn’t the term that was used. There was a two-family house, so we occupied the upstairs, and the owner of the building occupied downstairs. But yes, that is where I grew up. 01-00:01:32 Tewes: That is really interesting, the regional difference between the housing styles. 01-00:01:33 Real: Yes, yes. 01-00:01:35 Tewes: Can you tell me a little bit more about what it was like growing up in Brooklyn in the forties and fifties? 01-00:01:43 Real: Well, on one level it was very ordinary. This was a fairly residential neighborhood, tree-lined streets. We could play maybe not out in the middle of the street, but play on the sidewalk, sometimes even in the street. It was primarily a middle-class neighborhood, and in those days we weren’t even aware of these things, but it was predominantly white. And also, more important to my identification, it was predominantly Jewish—as was a good deal of Brooklyn and a good deal of New York in those days. But again, it was just something that you breathed in with the air. You went to the little shopping neighborhood nearby, and on practically every street there was a Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 2 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California kosher butcher, and there was a Jewish delicatessen every couple of blocks. There were elements of a much smaller city. We didn’t feel like we were part of some great, big, huge urban sprawl with all kinds of problems. 01-00:03:06 There was a park nearby, Prospect Park, which is Brooklyn’s equivalent of Central Park, and we used to go there all the time for a variety of things. In the summer, there was a lake and you could rent paddleboats and go out on the lake. In the winter, there were little hills, and we used to pull our sleds over there and sled down the hills. Prospect Park was one of our hangouts. And then close by to Prospect Park was the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, and we also spent a lot of time there. Gorgeous, gorgeous flowering cherry trees. It was a gift of Japan. It’s still there to this day, and it is still one of the great prides of Brooklyn. But my mother always used to take us every spring when the cherry blossoms were in bloom, and we’d walk up Cherry Lane and admire the beautiful blossoms. That would be about the time—and even earlier than that—some of the very, very earliest of the bulb flowers would come up, little bluebells, and then after that daffodils. And so we’d go to the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens to look at those. 01-00:04:35 And then sort of right across the street or very nearby to both of those parks was the Brooklyn Zoo, and I spent a fair amount of time in the Brooklyn Zoo, also. Which I do have to say is—I’m thinking about it now—it may be that some of my earliest social justice feelings were born in that zoo, because I always felt very, very sorry for the animals. And this was a very old-fashioned zoo, so they were mostly—they weren’t in cages, but they were in fairly small enclosures, and it was obviously very artificial. I remember writing a story when I was in elementary school about how a magic spell descended, and the animals all were released, and the human beings were all put in the zoo enclosures. So I obviously felt some stirring of something at the time. 01-00:05:42 And then I went to public school in Brooklyn. Well, I went to a public elementary school. The schools in New York City, at least at that time— thereby avoiding this problem that San Francisco seems to be having with its schools—the New York City schools were not named, at least the elementary schools; they were all numbered. I went to P.S. 241, and there was nothing strange about that. I have very fond memories of that school. And that was, at the time, one of the few remaining K-8 schools in New York. New York was just in the process, at that moment, of transitioning to junior highs. And junior high school in New York at that time was seventh, eighth, and ninth grade, so then you entered high school in tenth grade, which was a little bit weird. But I didn’t go through that because P.S. 241 was K-8, so I graduated from eighth grade and then went into high school in ninth grade. And then, of course, when tenth grade came around, our class just blew up in size—probably more than doubled in size as all the kids from the K-6 schools came pouring in. Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 3 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California 01-00:07:25 But anyway, I went from P.S. 241 to Erasmus Hall High School, which at that time was one of the best academic high schools in the city. It wasn’t a specialized school. It was just a regular public high school, but in large part because of the demographics of the area that it covered, it pulled from a lot of middle class and also a lot of Jewish neighborhoods. It tended to have a fairly bright student body and it tended to offer a fairly rigorous curriculum. There was a kind of a triangle of three schools: there was Erasmus, Midwood [High School], and Madison [High School], and all three were excellent, excellent regular public high schools. We weren’t talking, at this point, about the Bronx High School of Science or something. These were just regular neighborhood high schools, but they all had great reputations. Kids could graduate from those schools and go to really good universities, and they came out with just a superb education. 01-00:08:46 Erasmus was probably the most diverse of the three schools, because we pulled from a number of different neighborhoods, but it was also—and this again was politically correct, and it was the way things were done in New York at the time—Erasmus was what they called [makes air quotes] tracked. In other words, there was a college-bound academic track, and then there was a kind of an intermediate track, and then there was—I can’t remember what they called it, but it was the kids who took shop and who had no intentions of going beyond high school and going to college. Vocational, that’s the word I was trying to think

This is a transcript of an interview with Mimi Feingold Real for the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project conducted by Amanda Tewes on February 9, 2021. Real was born in Brooklyn, New York, on May 31, 1941, and grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in Brooklyn, which was predominantly Jewish. She describes her childhood as ordinary and notes that they had a park nearby, Prospect Park, which was Brooklyn’s equivalent of Central Park. She mentions that the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens was close to the park, and her mother used to take them there every spring to admire the cherry blossoms. Real also mentions that she spent a fair amount of time at the Brooklyn Zoo, which was old-fashioned and made her feel sorry for the animals.

Real attended public school in Brooklyn, and her elementary school was named P.S. 241. She has fond memories of her time there. Real notes that New York City schools were not named at that time; they were all numbered, and this prevented the problem that San Francisco was having with its schools. The interview provides insight into Real’s childhood and the cultural and social environment in which she grew up.

Could you summaries in 150 words the following text: —and that that must have shaped the stories about your early life. Did your family have stories about this time or what that meant for the community? 01-00:10:09 Real: You know what, that’s an interesting question, because the simple answer to that is no. My parents—my father, [Abraham Feingold], was too old at that point to have been drafted. I think the major impact was something that I never even was consciously aware of, and that is that my mother’s obstetrician, who should have delivered me, was drafted, was sent off to serve in the Army as an Army medic, and so she, [Elizabeth French Feingold], was turned over to another doctor. So it was some other doctor that she didn’t really know who delivered me. And the other thing, because I was too young—I was a baby, you know, I was a toddler—the thing I do remember Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 4 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California were the signs. There were signs indicating where there were bomb shelters or—and I don’t even remember now what the signs said, but I can remember various shapes. Like there was one sign that had a big triangle on it, and most of the signs were yellow with black printing, but I was too young to even read. So that’s the only impact that I can remember. 01-00:11:29 Tewes: Well then of course, years later more discussion comes out about the Holocaust, and that part of World War II. Was that something that impacted your family thinking about—as a Jewish family? 01-00:11:44 Real: Again, you know, it’s really interesting—again, the simple answer to that is no. Because we didn’t have any—aha, I know why. We didn’t have any family that lived in Germany or even in Eastern Europe. And to the extent—my father came from—was born in Russia before the revolution, before the Russian Revolution. He was born in the Ukraine, but his family managed to escape when he was only seven years old. So he had family in Russia, but the story had been that during World War II, in anticipation of the German occupation and the German invasion of the Soviet Union, a lot of the people in the Ukraine were relocated to the other side of the Ural Mountains, and that included my father’s family. He had managed to keep in touch with them. He had actually, I think, gone back to visit them in—before he met my mother, back in the 1920s or 1930s. By the time of the war, he had lost touch with all of them, because they had all been relocated. Again, that’s the family lore. 01-00:13:24 And even then, I guess there were mass, mass murders in the Soviet Union, but whether any relatives of mine were victims of that, I don’t know. So I guess I always knew about the Holocaust. I don’t remember it being a big thing that my parents talked about. They were more concerned with what was happening in this country. 01-00:13:56 Tewes: [laughs] Yes, and I do want to get to that. 01-00:14:00 Real: And also, my mother was not Jewish, so—and again, that was—I was always aware of that, but it was never something that was bad. It just was. And interestingly enough, my father’s father, who was an Orthodox Jew to his dying day, when his health deteriorated and his wife had already passed away, he came to live with us. He had three sons, and of the three sons, the only one who would take him in was the one with the non-Jewish wife, which I always thought was interestingly ironic. And so he

In this text, the interviewee is asked about her family’s experiences during World War II and the Holocaust. The interviewee states that her father was too old to be drafted, and the only impact she remembers was seeing signs for bomb shelters as a toddler. Her family did not have any stories or discussions about the Holocaust because they did not have any family in Germany or Eastern Europe, and her father’s family had been relocated to the other side of the Ural Mountains in anticipation of the German invasion. Although she knew about the Holocaust, it was not a big topic of discussion in her family, who were more concerned with what was happening in the United States. Interestingly, the interviewee’s mother was not Jewish, but her father’s father, who was Orthodox Jewish, came to live with their family in his old age, despite his other sons being unwilling to take him in.

Could summaries in 200 words the following text: Thank you, that’s good background. I think now is a good time to ask you, for the record: what was your given name, your birth name? Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 5 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California 01-00:15:06 Real: Okay, so my birth name is Miriam, and I was named for the biblical Miriam. But I was almost never called Miriam, even as a young child. The only times “Miriam” was ever used was when I was about to be disciplined, and my father would call me over. You know, “Miriam, come here.” And I would associate “Miriam” with being in big trouble about something, so that there was an assortment of family nicknames. But by the time I got to elementary school and high school, I was—actually, the way New Yorkers pronounced M-I-M-I, at least at that time, was “Mihmee,” so I was “Mihmee” all the way through high school. And then the story there is that another girl from my class at Erasmus was also accepted at Swarthmore [College], and her name was also Miriam. And her nickname, of course, was “Mihmee.” And she descended upon me and said that here we were going to this small college, and it was high time that we distinguished ourselves, so one of us had to be— could stay “Mihmee,” and the other one had to be “Meemee.” It was clear, by the way she said it as to who was going to be “Mihmee.” So that’s how I became Mimi. [laughs] So from college on, I was “Meemee” and she remained “Mihmee.” And I don’t know what ever happened to her. [laughs] 01-00:16:56 Tewes: But it seems to have worked out. You already started speaking a bit about your parents and your family, and I was wondering if you could just tell me a little bit more about them and their backgrounds, and then of course their livelihoods? 01-00:17:09 Real: Let’s start with the livelihood, because that’s the easiest one, and that is more or less how they met. My father, at that time when they met and married—and for most of my young childhood—was a high school math teacher. He taught primarily at a school called Manual Training High School—I don’t even know if that’s still in existence—in New York. My mother had majored in college in English, and through a very, very sweet line of reasoning that she went through, she wanted to do something that was useful and that would help people, and at the same use her English background. She made two lists: one of them of how to use the English background, and the other was how to be useful. Apparently, the only element on each—that was on both lists was librarian, so she became a librarian. And then she worked for many years as a high school librarian, also in Brooklyn, and that is how she met my father. I don’t think she was at the same school, although I’m not absolutely positive. But I think they met at a party, you know, some sort of a get-together of teachers. Anyway, they hit it off and decided to marry, much to the distress of both of their sets of parents, but they went ahead with it anyway. 01-00:18:52 The other major important thing to know about them is that from fairly early on, for both of them in their adulthood, they had become very progressive and left wing in their thinking. And I don’t know exactly when they joined the Communist Party, but they were members of the Communist Party, which at Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 6 Copyright © 2022 by The Regents of the University of California that time was not—did not carry the stigma that it carries today. Obviously, they were still very much outsiders and radicals. But what the communists were in that period, where it was a period of pretty much political conformity, the communists were some of the only people who were fighting for social justice, who were fighting for civil liberties and civil rights. Communists founded, or were members of, a whole range of organizations, which would later get smeared with the name of communist front. But they were not trying to overthrow the government of the United States by force and violence; they were not trying to eliminate capitalism. The Communist Party internationally, at that time, as I understand it, had moved away from that agenda, from the agenda of world revolution, to working