Louise has kindly written this blog about her new paper in Biological Conservation

The contribution of scientific research to conservation planning

To read the scientific publication that this blog is based on, click here.

Introduction: Questioning the value of research

Understanding the contribution of scientific research is of great importance to research fields that claim to have direct relevance or application to action on the ground. There is a strong feeling in the conservation community that research should be conducted not only for the pursuit of knowledge, but also to meet the needs of practitioners and decision makers.

One field that has strong links to action on the ground, and that is of particular interest to myself and other researchers within our MEP group, is conservation planning. Conservation planning is the process of “deciding where, when and how to allocate limited conservation resources” (Pressey & Bottrill 2009). This may involve, for example, understanding the threats to a species, and then identifying and implementing actions that would most effectively mitigate these threats. At the other end of the scale, conservation planning may involve assessing existing protected areas within a country and then identifying where new reserves should be placed to achieve habitat representation across the protected area network. Planning is therefore an essential tool in practical and strategic conservation management.

Conservation planning as a tool to achieve international biodiversity targets

Conservation planning also plays an important role in achieving international biodiversity targets. Since 2010, the global conservation community has been striving to achieve a set of twenty targets, called the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. These targets were set by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), with the aim of halting the global loss of biodiversity by 2020. 192 countries plus the EU are signed up to the CBD, each of them committed to this ambitious goal. The CBD has certainly pushed conservation up the political agenda, however with 2020 fast approaching, we are not on track to meet the Aichi Targets.

Application of a novel method to review the literature

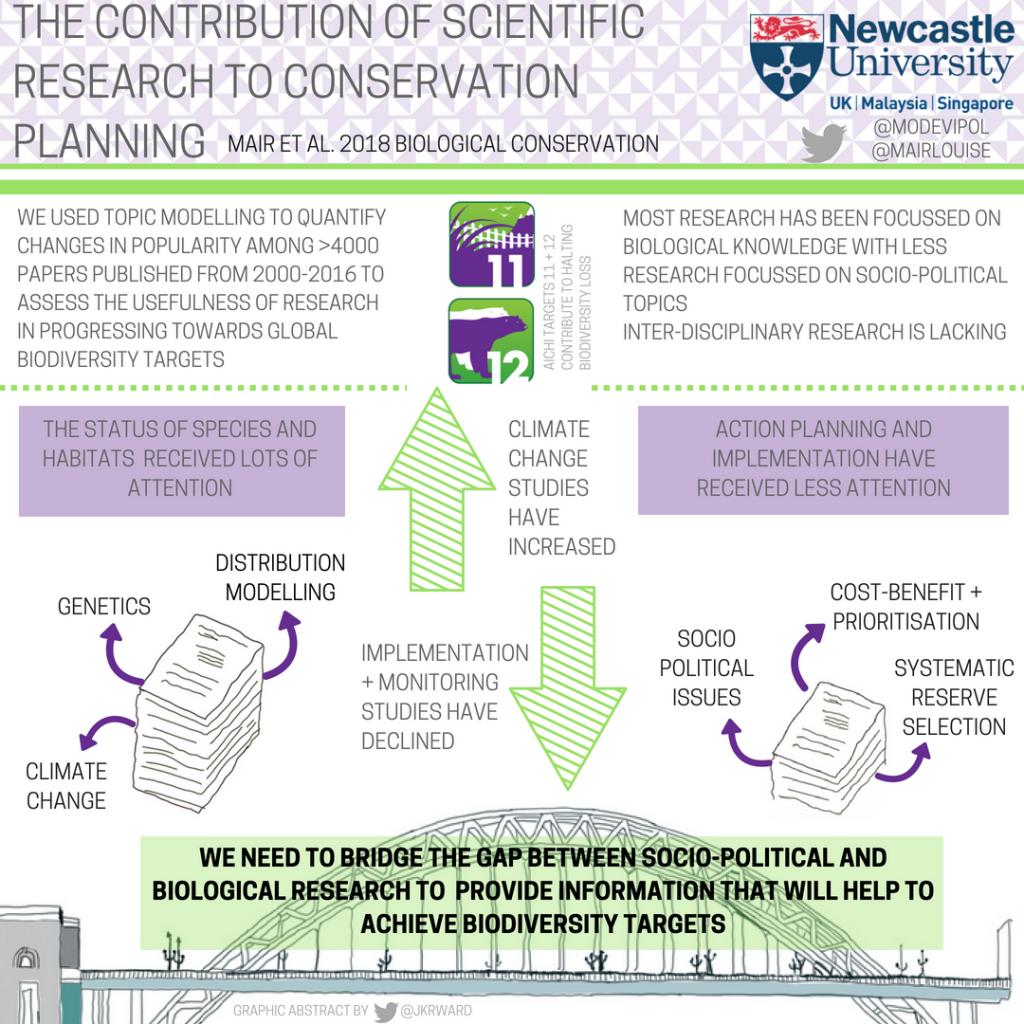

Having recognised the importance of conservation planning for achieving biodiversity targets, and that at a global level we are failing to achieve these targets, we were interested in understanding what contribution scientific research has made to conservation planning. This initially seems like a reasonable question, but a preliminary search in Web of Knowledge covering the years 2000-16 returned an overwhelming 4,471 articles. Reviewing such a large volume of literature requires an innovative approach, and so my MEP colleagues and I adopted a novel method, called topic modelling.

Topic modelling is a statistical tool used to assess the content of articles in a body of literature. The model identifies topics present in the literature based on the co-occurrence patterns of words in the article abstracts. This provides a quantitative framework for summarising themes and analysing trends in articles that cover a wide range of biological, spatial and temporal scales. Topic modelling was therefore an ideal tool for tackling this mountain of literature (for a great article demonstrating the approach in ecology, see Westgate et al. 2015).

The scientific literature on conservation planning neglects the social sciences

We found that the scientific literature on conservation planning was diverse, but it was dominated by biological rather than socio-political research. This might seem unsurprising given that conservation tends to be thought of as a biological discipline but, more than three decades ago, conservation was defined as dependent on both biological and social sciences (Soulé 1985). Indeed, it is the socio-political context (i.e. support and cooperation from locals and governments) that ultimately determines the success or failure of a conservation project.

This preference for biological research is borne out in the attention given to the different stages of conservation planning. Very loosely, conservation planning has three stages:

1. Status Review involves assessing the current status of, and threats to, species or areas;

2. Action Planning involves determining what actions should be taken;

3. Implementation involves carrying out and monitoring the planned actions.

We found that research into the status of species and habitats (primarily biological areas) was the most prevalent, with the process of action planning receiving considerably less attention, while implementation (which requires greater emphasis on socio-political considerations) attracted by far the least research.

This pattern is problematic, as there has long been a concern in conservation planning that there is an ‘implementation gap’, in other words, knowledge is rarely translated into action. Champions of evidence-based conservation have for decades bemoaned the lack of research into what works and what doesn’t work (e.g. Sutherland et al. 2004), yet our study indicates that the scientific community continues to neglect implementation.

The scientific community could do with building bridges

We also found weak links between socio-economic and biological topics, indicating a general lack of interdisciplinary research. This means that, for example, an article primarily about species genetics (which is a biological Status Review topic) rarely considered how the data could be used in Action Planning or Implementation. This lack of ‘joined up’ research means that the literature is highly fragmented and, in many cases, the applicability to practitioners and decision makers is unclear.

We suggest that the applicability of research could be improved, and the implementation gap closed, if conservation planning research was more frequently designed and executed in collaboration with both practitioners and relevant stakeholders. This would make the link between the biological and social sciences, and join up the different parts of the planning process to give more holistic outputs.

So what does this all mean for conservation?

Our interpretation is that, as a scientific community, we are continuing to conduct research within unidisciplinary realms, which is ultimately hindering our ability to produce research that is valuable to action on the ground. We are also missing the opportunity to learn lessons from the many conservation plans that are implemented but not reported in scientific publications. Shifting the focus and reporting of research is clearly challenging, but part of making progress requires understanding our past and current behaviour, which is where studies such as ours help shed light on what we’re doing and what we could be doing better for conservation planning.

Summary of key points

- We assessed the contribution of scientific research to the field of conservation planning by applying topic modelling to a body of literature consisting of 4,471 articles

- Research into the status of species and habitats was most prevalent, the process of action planning received considerably less attention, and implementation attracted the least research of all

- The scientific literature was dominated by biological rather than socio-political research, and showed a lack of inter-disciplinary research

- The number of publications on implementation and monitoring declined over time, suggesting that limited efforts have been made to address the “implementation crisis”

- We suggest that filling research gaps, through integration of the social sciences and placing greater value on evidence syntheses, would push scientific research towards greater applicability

This blog is based on: Mair, L., Mill, A.C., Robertson, P.A., Rushton, S.P., Shirley, M.D.F., Rodriguez, J.P., McGowan, P.J.K., 2018. The contribution of scientific research to conservation planning. Biological Conservation 223, 82-96.