Commercial Awareness – A Multi-Faceted Concept

It is, as ever, crucial for law students entering the workplace to be commercially aware. But the concept of commercial awareness is no longer monolithic. Craig Sharpe, Marketing Manager, has written the piece below on its developing nature. Craig, who has more than 30 years in the legal field, will be providing further insights into this and other legal practice issues at a careers service event taking place on 7th February (details to follow).

Commercial awareness – multi faceted and one size doesn’t fit all

Travelling around the country visiting and speaking at different Universities, it’s clear to me that students are increasingly aware of the changing nature of lawyering. The buzzword that often summarises the major changes in legal practice and the market is “commercial awareness”.

When I talk to students it’s also clear to me that what constitutes commercial awareness is not always clear. The term can mean different things to different people and, crucially, it often means something quite different depending on the type and size of law firm.

Commercial awareness is more important because there has been a shift in the legal market

The traditional role of lawyers as pure professionals has largely disappeared over the last 30 years. When I say pure professional I mean a relationship where lawyers were used to protect clients without needing necessarily to understand much about the client’s business, where legal costs weren’t generally negotiated much by clients, and where the legal market wasn’t that competitive.

Things have radically changed, primarily based on a huge increase in the number of lawyers without the same increase in the demand for legal services.

Clients now shop around for lawyers and their expectations have changed.

For the largest law firms, on a basic level, commercial awareness tends to mean an expectation that trainee applicants demonstrate an understanding of: (1) how business works and; (2) the importance of understanding different business sectors. This is often the basic definition of commercial awareness, described in this article, and one which most students provide when I ask them what commercial awareness means. However, it actually involves a lot more and if students can demonstrate they understand it on a deeper level, this can be a differentiator.

Justifying legal fees and proportionality

Even the magic circle firms are now having clients demand justification of charging rates and their proportionality. The latter is especially important – the historical model was that lawyers would advise clients that, as professionals, they had to do a job thoroughly and that might mean costs could seem disproportionate to the commercial risk/advantage to the client. Clients, generally, simply don’t buy that argument any more. So, being commercially aware means understanding that clients almost always looking at whether legal fees are proportionate from a business viewpoint.

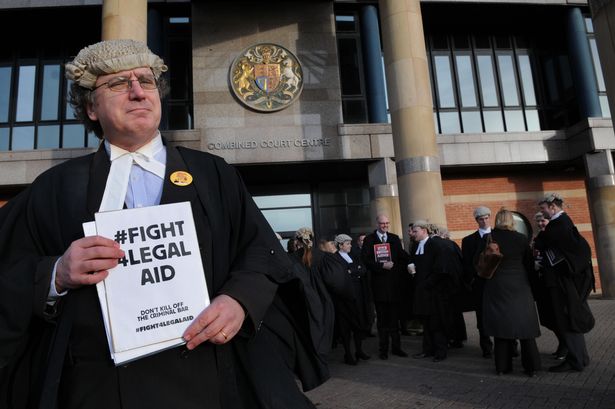

Commercial awareness can mean risk sharing

Historically, lawyers wouldn’t even consider sharing some of the commercial risk with clients and the practice was also seen as unethical. Times have changed and for some types of law, clients now expect their lawyers to share some risk. This typically applies to high value litigation, where increasingly, litigation funding (more here on the growth of litigation funding) and some form of partial risk sharing, contingency or no win no fee is being utilised.

So, lawyers and law firms are having to exercise commercial judgment as well as legal judgment in deciding whether to take on a potentially lucrative but risky case. In doing so, business considerations can also apply. For example, with a high value, multinational client, the commercial awareness aspect may also include consideration of how the client may view the firm going forward if the firm rejects risk sharing out of hand. In other words, if that clients goes elsewhere for a litigation matter, might they not come back for other types of work such as huge corporate transactions?

Internal commercial awareness

The example given above demonstrates that commercial awareness often has an internal as well as an external aspect. In addition to understanding clients, markets and so on, lawyers are increasingly being forced to adopt a business as well as professional approach. Being part of a law firm means understanding the internal commercial considerations that go on within that firm. Law students may well ask “how can law firms expect me to know about their business when I apply, I don’t have access to that information?”.

Business challenges for law firms

That’s a completely fair point of course. However, law students can gain an understanding of the changing market and how that impacts firms of all sizes. Whether a student may apply to a huge law firm or a very small one, appearances of unabated success can be deceptive and firms of all sizes now face unprecedented competition. For a smaller law firm, internal commercial awareness may well mean understanding that for that size of firm, they would expect a trainee lawyer to get involved in tasks that are not traditional fee earning.

In a firm like Darlingtons, a typical small to medium firm where I work, we expect trainees to be open to getting involved in marketing initiatives. In a competitive market, every member of staff needs to have an open and adaptable approach which is team centric. This is an example of how we perceive commercial awareness.

It’s worth remembering that about 70% of lawyers or more do not work in the big firms, so students statistically who pursue a career as a solicitor are more likely to end up working in a smaller law firm.