– Colin Murray (Senior Lecturer, Newcastle Law School) colin.murray@newcastle.ac.uk

This post was first published on Human Rights in Ireland

Stop and Search certainly was the hot human rights news story of last summer within the UK. Schedule 7 powers under the Terrorism Act 2000 allow for extended powers to stop and search, and even detain for up to nine hours individuals in the context of ports and airports, for the purpose of assessing whether they are linked to terrorism. That police powers should be extensive in this context might be thought relatively uncontroversial. After all, the potential to trap hostages in such a confined space was attractive to terrorist groups long before the 9/11 attacks displayed the potential of using civilian airliners as weapons.

The problem, as so often is when counter-terrorism is at issue, is that when such exorbitant powers are assumed, legal systems can find it very difficult to constrain their abuse. The problem really comes to the fore when, as David Anderson QC, the UK’s independent reviewer of counter-terrorism powers, told Parliament on 12 November, criticism of the security services within the UK is often muted, partly because of national pride in their activities (dating from the work of the code breakers at Bletchley Park during the Second World War) and partly as a result of the 007 brand’s ongoing appeal.

This situation produces one key question. In rather feverish context of the security debate, and with a seemingly in-built national deference to the activities of the security services, what is to stop police and security officials from abusing extended stop and search powers? For over a decade the airport powers attracted little attention. This is especially the case when their operation is compared to the furore which surrounded the day-to-day use of extended counter-terrorism stop-and-search powers on the UK’s streets, which ultimately led to the European Court of Human Rights finding a breach of Article 8 ECHR. The police seem to have appreciated, as Joshua Rosenberg picked up from Anderson’s reports on the use of Schedule 7, that the power was not simply valuable, but that “like all valuable things, it needs careful handling”.

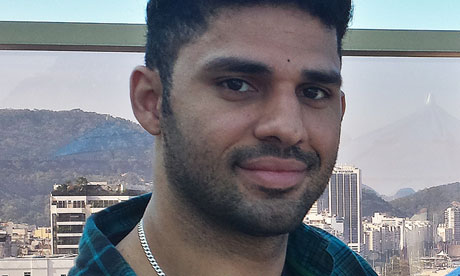

The powers suddenly became an issue of national importance with the detention for nine hours at Heathrow of David Miranda (pictured above), partner of US journalist Glenn Greenwald. The police were investigating whether Miranda had in his possession US national security documents received from the NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. Embarrassing for a key ally perhaps, but where is the basis for using counter-terrorism powers, Greenwald and his supporters asserted? Miranda was not a member of any banned terrorist group. For the police, however, the link between these security-related documents and counter-terrorism powers was indirect, based upon the damage that the release of these documents could do to counter-terrorism operations. This attempt to link his case to terrorism has been likened to a “conjuror’s trick” by barrister and blogger Adam Wagner.

Yesterday the High Court ruled that a challenge to the legitimacy of this exercise of the power and to the compatibility of the power generally with the freedom of expression under Article 10 ECHR could not succeed. First off, Lord Justice Laws (giving the lead judgment) quickly dismissed the contention that the power had been used for an improper purpose, ie, that the examining police officers’ purpose in stopping Miranda was out with the scope of a counter-terrorism power. Laws LJ summed up the purpose of the Detective Superintendent involved stopping Miranda (at [24]): “given the connection with Mr Snowden and the latter’s movements, that the claimant might have been concerned in acts falling within the definition of terrorism in s.1 of the 2000 Act which might be carried out by Russia and designed to influence the British government”.

The key factor is that the court accepted that the definition of terrorism under section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2000 was broad enough to provide a basis for this arrest, notwithstanding that Miranda himself could not be described as a “suspected terrorist” (at [29]):

[T]he bare proposition that the definition of terrorism in s.1 is very wide or far reaching does not of itself instruct us very deeply in the proper use of Schedule 7. … S.1(2) is concerned only to define the categories of “action” whose use or threat may constitute terrorism: not to impose any accompanying mental element. Similarly, the expression “concerned in” in s.40(1)(b) is not to be taken to import the criteria for guilt as a secondary party which the criminal law requires in a case of joint enterprise.

As long as Miranda was linked to Snowden, who was intent on publishing materials which would influence government policy and could endanger the lives of UK agents, this was sufficient for the court to find that the purpose was proper (at [32]):

Putting all these features together, it appears to me that the Schedule 7 power is given in order to provide a reasonable but limited opportunity for the ascertainment of a possibility: the possibility that a traveller at a port may be involved (“concerned” – s.40(1)(b)), directly or indirectly, in any of a range of activities enumerated in s.1(2). If the possibility is established, the statute prescribes no particular consequence. What happens will depend, plainly, on the outcome of the Schedule 7 examination including any searches where those have been carried out. There may be a prosecution for an offence under the Act, or indeed some other offence; materials in the subject’s possession may be retained if the general law allows it; the subject may be released with no further action.

In terms of whether the stop was proportionate, in light of Miranda’s involvement in journalistic endeavour, drew Laws LJ into a detailed consideration of the freedom of the press in general. Whilst he appreciated that importance of the public interest in a free press, the proportionality of any interference had to be judged in light of other public interests, such as national security (at [46]):

[There is] an important difference between the general justification of free expression and the particular justification of its sub-class, journalistic expression. The former is a right which belongs to every individual for his own sake. But the latter is given to serve the public at large; … It follows that so far as Mr Ryder claims a heightened protection for his client (or the material his client was carrying) on account of his association with the journalist Mr Greenwald … [t]he contrast is not between private right and public interest. The journalist enjoys no heightened protection for his own sake, but only for the sake of his readers or his audience. If there is a balance to be struck, it is between two aspects of the public interest.

Whilst he was not willing to give carte blanche to a public official’s assertions of security concerns (see [57]), Laws LJ was clear that valid security concerns had been made out in this case, and that he would not substitute a journalists view of these questions for those of government (at [71]):

Journalists have no … constitutional responsibility. They have, of course, a professional responsibility to take care so far as they are able to see that the public interest, including the security of the State and the lives of other people, is not endangered by what they publish. But that is not an adequate safeguard for lives and security, because of the “jigsaw” quality of intelligence information, and because the journalist will have his own take or focus on what serves the public interest, for which he is not answerable to the public through Parliament. The constitutional responsibility for the protection of national security lies with elected government …

Wrapping up, Laws LJ concludes that the powers (limited to a ports and airports context) are hedged by adequate safeguards. For all that complaints have already begun regarding the level of respect accorded to elected decision makers in the security context, it seems that the strongest ground for appeal is this briefly addressed issue of safeguards. After all, it was the basis on which the general no-suspicion stop-and-search power was subject to major reform in the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, and is already under fresh review by David Anderson QC. This legal battle may be lost, the war over counter-terrorism powers looks set to rage on.