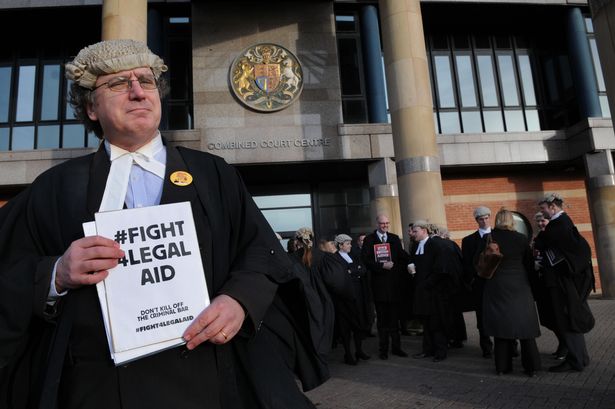

Image Source: http://www.gazettelive.co.uk/news/teesside-news/legal-aid-cuts-protesting-barristers-6472513

– Sophie Allinson (LLB Law, Newcastle University) s.allinson@ncl.ac.uk

“Today our worst fears have been confirmed, another round of cuts, after three years of cuts, cuts and more cuts“.

Nicholas Lavender QC

Uncertainty is a theme increasing in prominence throughout all practices at the Bar, but none more so than the Criminal Bar. Cuts to the criminal legal aid budget were confirmed yesterday, reducing the funding available by £220 million. Widespread opposition and strong condemnation has been voiced, with Nicola Hill, president of the London Criminal Courts Solicitors Association, damning the confirmation of the cuts as, “a shameful day in legal and criminal justice”. Such a measure of austerity will mean fewer people than ever before will qualify for legal representation, and worryingly, many will find themselves unable to afford access to justice. The closure of several high-profile chambers is indicative of the crisis facing the criminal bar. Barristers of the highest quality are struggling to fill their diaries. Many junior criminal barristers have made it plain that they cannot survive on their wages. Such a crisis begs the question, who could possibly still want to pursue a career as a criminal barrister?

It is true that cases will not vanish, there will always be crime. The law will not cease to operate simply because funding has been withdrawn. Representation, however, is in great danger of disappearing, as barristers seek to make ends meet in other fields of law. This raises extremely alarming questions about the possibility of miscarriages of justice and the upholding of democracy, as quality barristers are forced out. The legal profession has voiced their fury by holding a half-day demonstration. This is the first time barristers have completely withdrawn their labour in support of a cause, with a further strike planned. Those already trained within the profession are struggling to see a viable future for their career. Ministry of Justice figures show that criminal barristers have an average income of £56,000. However, Nigel Lithman QC, chairman of the Criminal Bar Association explains this is before all other costs have been deducted. Lithman argues the number of bankruptcies in the junior bar is increasing at an unheard of rate, with the majority struggling to meet the cost of living.

Junior barristers currently undertaking pupillages at criminal sets have reported annual incomes of no more than £24,000. To put this in perspective, this is equivalent to a basic cleaner’s salary and lower than entry level jobs in nursing, local government or the police. The amount of debt accrued in the years of university and graduate training outweigh the financial reward substantially. It is true that many are doing rewarding work which they are passionate about, yet the truth remains that these students will have financial obligations to meet. The old mantra of sticking with it to reap the eventual reward appears to have been wiped out. Hearings in the magistrates’ court are usually in the range of £50 – £80 and Crown Court work is increasingly scarce. The majority of those at the junior end are still saddled with student debt, combined with rising living costs, particularly on the South Eastern Circuit. The profession appears to no longer be economically viable.

It is true that in times of austerity, every publicly funded area must bear the brunt of cuts. Nevertheless, the cuts announced this week have been criticised as unprecedentedly harsh. The Ministry of Justice made few concessions, despite a sustained campaign emphasising the cut’s irreconcilability with the public interest. Consequently it is expected that skilled and experienced advocates will be pushed away from publicly-funded criminal work. Indeed some chambers have found themselves unable to continue operating. Tooks Chambers, having worked on landmark cases such as Hillsborough (although not as a criminal set), began dissolution in 2013, directly blaming legal aid cuts for their inability to continue.

What do these cuts mean for students? For those seeking a profession as a solely criminal practitioner, the outlook is decidedly bleak. Chamber sets specialising in criminal law rely overwhelmingly on cases funded by legal aid. The steady reduction in this source of income has left a large number of chambers economically vulnerable, and unable or unwilling to provide financial support to their pupils. For several sets, funding for pupils has been entirely withdrawn. The majority of those wishing to undertake the BPTC must now fund the absolute minimum £12,000 tuition fee entirely on their own, with no guarantee of a job upon completion of their training. If only a privileged minority can fund their course independently, surely the criminal bar is inaccessible to the majority of students who cannot justify this financial risk, especially without the guarantee of an income at the end.

However, attempts to support those who still seek a career at the Bar cannot be overlooked. The Inns of Court have pledged significant financial contributions in an effort to encourage chambers to continue offering pupillages in the short-term. The “pupillage matched funding scheme” will provide 50% of the fees offered to trainees by chambers. James Wakefield, director of the Council of the Inns of Court insists that the decreasing availability of opportunities for hopeful barristers will be tackled by the funding scheme. Of course, the introduction of this funding will prevent the profession from dominance by the financially privileged. On the face of it, those who cannot afford the onerous costs of the BPTC should not be deterred, as there will still be financial assistance available during training.

However, whilst the scheme may keep the opportunities for training open, what follows after that? Ultimately, with less paid work on offer for junior barristers, what good will a pupillage be? This has been acknowledged by the Inns, who have announced a review of the scheme in 2015. Furthermore it has been stated funding may be withdrawn entirely if the scheme proves unworkable. Critics of the proposal, including Nicola Hill, have already pointed out that the result will be an abundance of qualified junior barristers, fighting for the few remaining cases available. Whilst such a scheme may be successful in ensuring students are not deterred from undertaking training, it will be unsuccessful in finding these students work when they need it.

Nevertheless, during such times of uncertainty, it can only be a good thing that the doors to the profession are being propped open for as long as possible, denying them the chance to slam shut infinitely. The economy is recovering, albeit is slowly and incrementally. Whilst it is unlikely that the Government will restore the legal aid budget in its entirety, alternative courses of action will develop over time. Chambers specialising in criminal law will adapt to survive. It is expected that many sets will branch out into other areas, pursuing cases in fraud, bribery and regulatory law to bring in stable fees. This will certainly reassure those who plan on becoming a criminal barrister, however it must be noted that the type of casework is likely to be less socially rewarding than it has been over previous years, as the focus is changed. Those who were once drawn to the criminal bar to pursue ideals such as ‘innocent until proven guilty’ will find themselves working towards substantially different mantras.

Ultimately though, it is argued that it would be naïve to ignore the fact that the Criminal Bar appears to be a sinking ship. With those already in the profession being compelled to make the choice between abandoning, or being forced to walk the plank, students who are yet to finalise their career choices would be well advised to stay away from the profession. To those already at the criminal bar, the choice is clear-cut, leave voluntarily or wait to be forced out. Huge financial risk is unlikely to be outweighed, as the potential for reward is being increasingly reduced, with very little indication of an imminent return. There will always be crime, thus there will always be cases. But the availability of these cases, and the money gained from undertaking the enormous level of work demanded appears to render a choice to pursue a career as a criminal barrister as nonsensical. It is a saddening truth to realise that the criminal bar is no longer a realistic option for students with aspirations to become a barrister. With this said, it can only be hoped that as the economy commences its recovery, the legal sector may slowly begin its revival.