Shane Finan is a visual artist from Ireland who works with mixed media installation to create places. Through his art he tries to unthread some of the complexities and contradictions inherent in ‘networks’. Here he discusses these ideas in relation to ‘The Symbiocene’ – a world in which humans live mutualistically with the natural world.

“Infinity and nothingness are infinitely threaded through one another so that every infinitesimal bit of one always already contains the other.”

(Barad, 2012, p. 17)

The global, the local, the branches, the roots, the city, the rural, the home.

1. Complexity

In the 19th Century, people did not believe that extinction was possible. The complex idea of a species disappearing contradicted the popular belief that God would not allow a creature to die out. Thomas Jefferson believed he would one day astound the European continent by finding a living mastodon. The complex idea (extinction) contradicted the dominant belief (religious consistency) making it difficult for people to resolve.

Now, in the 21st Century, any five-year-old can explain extinction. This is an example of complexity, contradiction, and eventual resolution.

Any dynamic idea is complex, and art is great at untangling complex ideas. The literature of Beckett, Kafka or Lispector unpicked the complex ideas of existentialism. The music of John Cage untangled the roots and branches of forests and fungi.

In my art, I have looked at complex contradictions over the past twelve years. My focus is on the idea of ‘place’, and how perceptions of place differ from one person to another. The aspects that make up a place include history, communication, ecology and environment. No ‘place’ is a unique entity: it is part of a global whole. A wind will not stop at the edge of a field because the land beyond belongs to a different person: identity is more than borders.

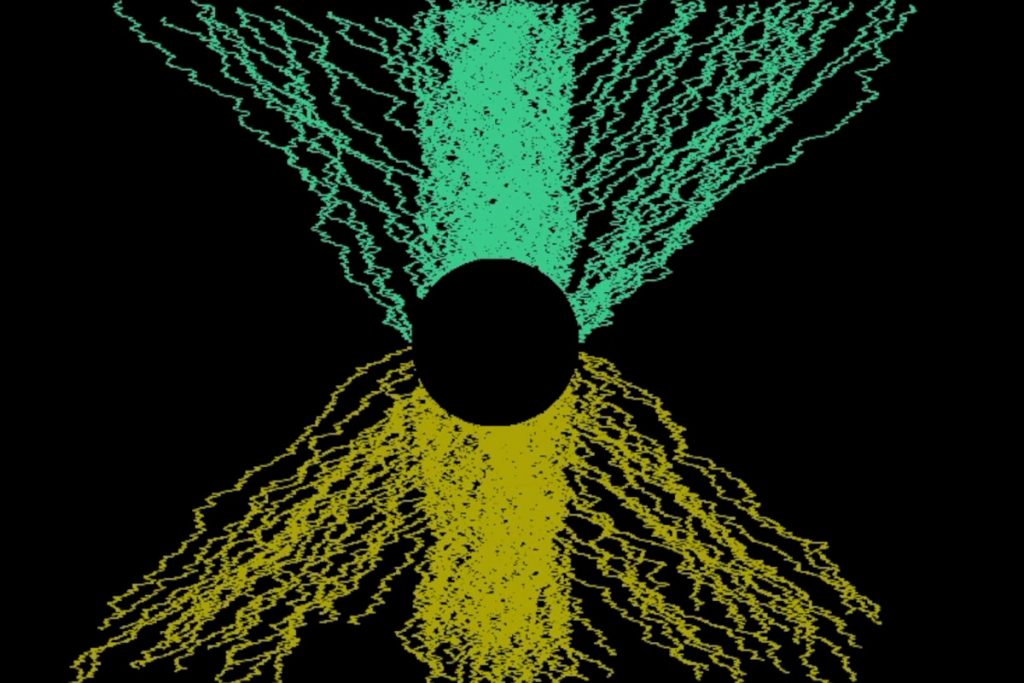

I am working on unthreading the complex ideas of ‘networks’: of people, and of plants (see ongoing videos from this project here).

2. Contradiction

Thinking about complexity often requires believing in ideas that are contradictory. A strong example that is common throughout the western world is the paradoxical belief that Jesus Christ was simultaneously god and man (Visser, 2015). This apparent contradiction formed the basis of one of the most widespread religions in the world and is widely accepted among Christians.

To understand two contrasting topics simultaneously, scepticism and curiosity are needed in equal measure. The Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico specialises in complexity, using areas as diverse as art, experiential philosophy and data analysis to understand complex aspects of our world. This combination of apparently disparate ideas leads to unusual or unexpected discoveries and is arguably the easiest way to overcome issues of prejudice or bias. By retaining complex thinking, the assumption is that a subject can be viewed from many angles: social, scientific, political, philosophical, historical, contemporary, artistic.

The multi-disciplinary application of different schools of thought applied to an individual subject creates an opportunity for questioning the subject in-depth, through its complexity. Further to this, collaboration between disciplines opens new possibilities of understanding.

3. The ‘Symbiocene’

Philosopher Glenn Albrecht believes that after the Anthropocene (the period where humans are having an unprecedented effect on the geology of our planet), we need to move into a way of living mutualistically with one another and with the natural world around us. He coined the term symbiocene to describe this idea of mutualism. Albrecht sees this as an activity across disciplines. It requires a major paradigm shift from the dominant belief system (competitive expansionism) to another (mutual collaboration).

To move out of a dominant belief system, it is important to first identify and challenge that system. The grave danger in prejudice is the ‘locking in’ of prejudiced ideas. For example, cognitive capitalism encourages the idea of constant growth through the extraction of natural materials, exploitation of human work and amalgamation of data. This dominant ideology argues, from a position of power, that economic capital leads to better societies. This may be true, but without a competing ideology, it is impossible to test and verify.

Other philosophers, including Rosi Braidotti and Judith Butler, highlight this need for a mutual approach across different areas, from science to technology, from sociology to environment. Butler has lamented that this view is often seen as naïve, but points out that the naivety is suggested by those in the same dominant belief system (Butler, 2020).

4. Networks

The overall goal of my research into networks is to point to how ideas and practices can be brought together. Part of the aim of this work is to offer a different perspective on the world. For example, one view of nature is that all species are in competition, pushing for survival of the fittest. In this view, flowers evolve to control insects and make them transfer their pollen. An alternate view is that nature is collaborative: flowers offer food to insects, who in turn transfer pollen.

A belief in a mutualistic worldview requires this paradigm shift in thinking about how the world works. This is complexity and contradiction. My artworks are built to encourage this mutualism, by encouraging a new type of network between people and people, and between people and other organisms. This would be a small step in moving toward a symbiocene.

—

The universal.

—

All images are copyright of Shane Finan

—

References

Barad, K. (2012). What Is the Measure of Nothingness? Infinity, Virtuality, Justice. 100 Notes–100 Thoughts. dOCUMENTA (13). In: Hantje Cantz Verlag.

Butler, J. (2020). The Force of Nonviolence: The Ethical in the Political: Verso Books.

Visser, M. (2015). The geometry of love: Space, time, mystery, and meaning in an ordinary church: Open Road Media.