Dr Lisa Garforth is a senior lecturer and the Postgraduate Research Director for Sociology at Newcastle University. Recently, our colleague Audrey Verma and her collaborator JC Niala ran the Hope and Resistance in the Anthropocene symposium. In the second of two related blog posts, Lisa links themes from the event to her work on imagining green futures. This post is based on a conversation with Natalie Partridge who transcribed it and helped frame the ideas.

My work has for a long time explored how we imagine better futures in relation to nature and the environment and how sustainable societies might look. Although a lot of environmentalism is about crisis, loss and fear for the future, there have also been philosophies, policies, polemics and fictions trying to envision a different model of human wellbeing and a different relationship with nature. Much of radical ecopolitical thought and writing since the 1960s has said that there can be better ways of living with, and in, ‘more-than-human’ communities – with a focus on connection, care and caution rather than the emphasis in much of the global North on consumption, commodities and economic growth.

The idea of the Anthropocene is a moment of realisation or recognition that what we conventionally call ‘nature’ has been thoroughly made and remade by social actions and systems. In scientific terms, the Anthropocene marks the point at which humans supposedly become geological actors and when the outcomes of human impacts become threatening to all planetary life. So, older ideas about saving or caring for nature, or saving ourselves, by getting closer to nature, become problematic in two main ways. The notion of a separate nature becomes extremely unstable, and the idea that we can make or remake the future is undermined by the earth system threats already in train.

The climate-changed future

There’s something about the physical dynamics of climate change, in particular, that erodes the space for imagining better futures. The emissions that are probably going to cause global temperature rises, sea level rises, and climate chaos have already happened. Without major geo-engineering this can only be mitigated, not removed. The climate changed future is already unfolding in the present. The climate modelling that explains these dynamics induces a constant sense of belatedness: the right time to act for a better or at least liveable world has always already passed. The solutions currently proposed by technoscience entrepreneurs and neoliberal government policy tell us that all we need is more of the same: technology, economic expansion, efficiency logics.

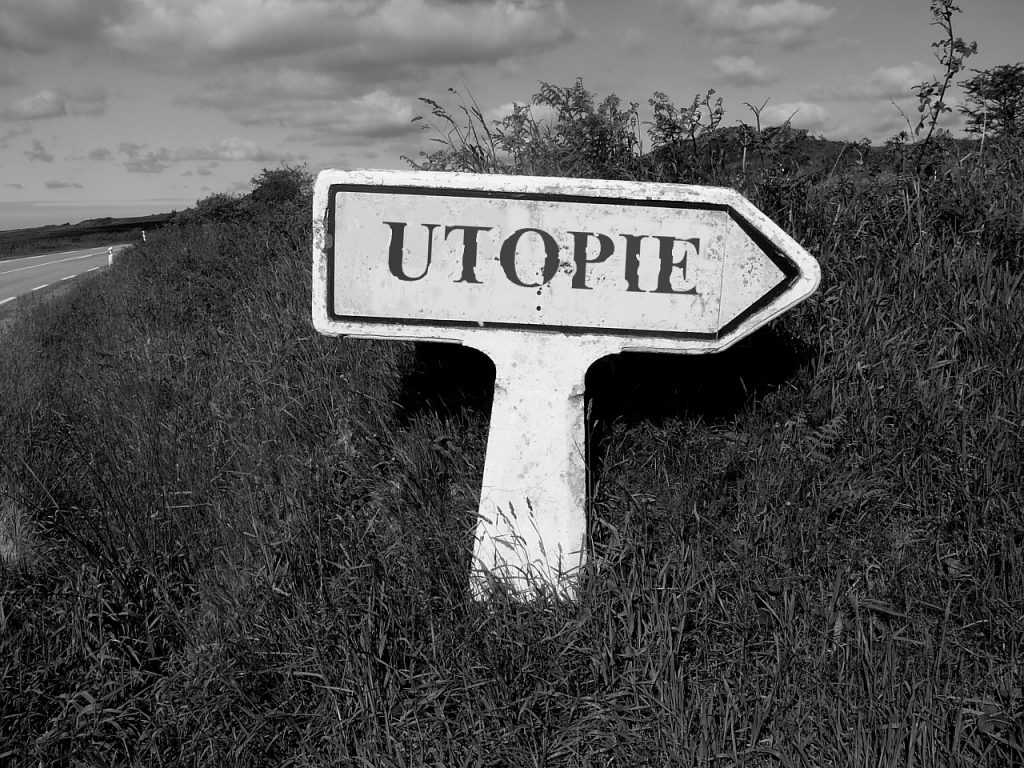

So what kinds of utopian imaginary are possible in relation to climate change and the Anthropocene? I think speculative fiction has done a lot to speak to us about alternative Anthropocene futures with utopian dimensions. The cliched image of contemporary futures in science fiction is dystopian blight and post-apocalyptic ruin. It can be easy to dismiss darker future visions as nihilistic or failing to inspire action. But that flattens all dystopias into a monolithic pessimistic message and assumes that post-apocalyptic scenarios are literal predictions. Good speculative fiction is much richer and more complex than that – and so are its readers.

Dystopias and utopias: A different way of thinking

A different way of thinking about speculative fiction is as a kind of lay sociology of what John Urry calls “probable, possible and desirable” post-carbon futures. Speculative fiction creates alternative worlds in text. As readers, we can use them to explore what it might feel like to live in very different kinds of societies. In the last thirty years, many of the best science fiction writers have been the most utopian, and also the most sociologically astute: Kim Stanley Robinson, Ursula K Le Guin, Octavia E. Butler. Between them, they have written compelling social-ecological futures – often apocalyptic or dystopian, but always insisting that we can, and should, imagine better ways of living and being.

Butler was one of the earliest science fiction writers to extrapolate the social and political implications of climate change in the context of social and racial injustice, anticipating current tensions emerging in California over land and water use and contemporary authoritarian and populist politics. Kim Stanley Robinson has approached environmental and climate challenges with an unflagging but always adapting utopianism in his fiction over the last 30 years. ‘Utopian’ here doesn’t just mean formal visions of sustainability and security. It means refusing the anti-anti-utopianism that says things can only stay the same or get worse. Thinking about hope and resistance for the Anthropocene, we are going to need all the positive resources we can get to change an unsustainable, climate disrupted global capitalist system. These novels can help both publics and sociologists imagine it otherwise.