Jake Pointer is a second year Sociology PhD student at Newcastle, studying the experiences of migrant workers in the British meat processing industry. Here he writes about something external to his research but just as important to him – mental health and how it can be approached through a sociological lens.

In general, there are two social issues which I seriously care about. I’m sure most people who know me can guess the first, it begins with a V and involves eating lots of grass if the latest internet memes are accurate. The second is perhaps not so easy to decipher as I rarely talk about it: mental health problems (MHPs). The reason, which I imagine is the reason for most people who take an interest in this area, is because I suffer, sometimes quite severely, from MHPs, specifically the D-word (I dislike that word, I’m not sure why). Here are my thoughts on some things that can be done about it at a societal level.

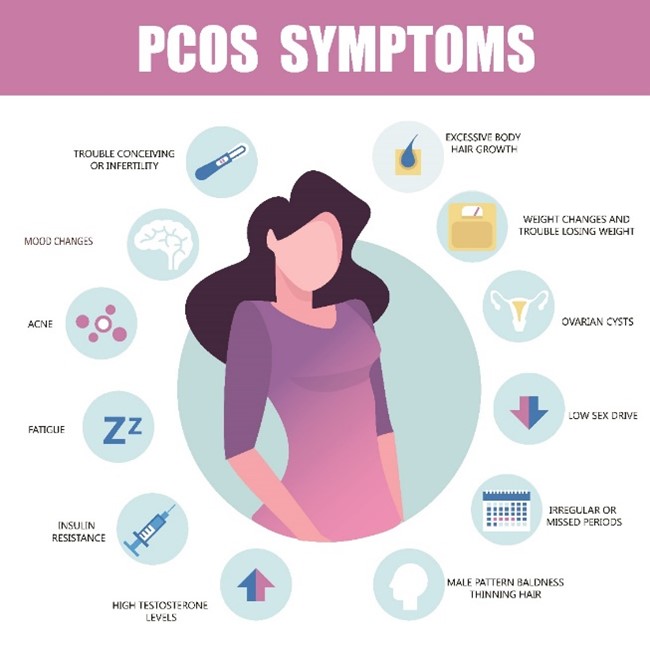

First, it’s worth taking a few moments to consider what mental health is and what happens when it goes wrong. Everyone has mental health, but I think it’s only when it starts to deteriorate that people give it much thought. As MHPs have been kicking down the societal door for some time now it is affecting us more though, I’m sure most people at least know somebody with a mental ailment. Here’s what an MHP might look like based on what I know and my own experience. The individual with the D-word will likely spend much of their time in bed, often due to an inability to get up and disruptions to sleep patterns. Their appetite may drastically increase or decrease. Socialising and working become harder, perhaps impossible. Things once interesting become mundane. Jokes are no longer funny. Anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure, will likely have a strong grip on the individual’s psychic windpipe. To put it lightly, it’s not a great place to be.

A New Approach

The current method for dealing with these ills is to focus on treatment, that is, waiting until people become mentally entropic and then addressing the problems. This may involve medications, therapy, diet changes, exercise, mindfulness practices, diary keeping and so on. These are all effective tools, but, in my opinion, more focus should be on prevention. It is clear that MHPs are more likely to arise when people are exposed to certain influences. These include, but are not limited to, an unstable homelife, childhood abuse, loneliness, over exposure to social media, traumatic events and unemployment. More focus should be on neutralizing these. A new field of psychology is investigating whether nutrition can affect mental health. This also holds promise. Additionally, I believe that MHPs have been romanticised somewhat; with narratives of ‘battling’ or ‘overcoming’. Viktor Frankl might identify this as making meaning in suffering, but it would be better to allow people to find meaning whilst in a state of mental flourishment. One example of how prevention could be implemented is a ‘mental health day’ at school, giving children the knowledge and tools to not only cope with any issues, but to identify potential influences before they start to wreak havoc. Everybody now knows smoking is bad, thus many people have now chosen to not smoke in the first place – an example of prevention via education. Perhaps the same can be done for MHPs. I’d even like to recommend a potential reading for school students, Flow: the psychology of optimal experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. I read this recently and it is overflowing with researched-backed information on how to have a deep impact on your own mental welfare and those around you in many areas of life.

With all this in mind (excuse the pun), it is perhaps unrealistic to believe we can have a hundred per cent mentally healthy society. Either way, I’m convinced the best way to stop MHPs arising is to prevent them from getting a foothold in the first place because once they do it is no easy task to repeal them. I don’t like it when people say mental health is the same as physical health, because I think they are quite different. Nonetheless, we have successfully eradicated plenty of physical diseases in the past. Can the same be done for MHPs though? I’d like to think so, but this is up for debate. We’ve always known that mental health rates fluctuate depending on certain social influences, something Durkheim demonstrated back in the early day of sociological thought. If we can identify the influences in the 21st century, perhaps we can start to take steps to reduce them. It is a success when an individual removes the Atlasesque weight of an MHP from their cerebral shoulders. But whilst it may not be recognised as such, it is an even greater success when those same shoulders never have such a load on them in the first place. That should be the goal.

References

Csikszentmihali, M. (1990) Flow: the psychology of optimal experience, New York: HaperPerennial.

Durkheim, E. (2006) On Suicide, London: Penguin.

Frankl, V. (2004) Man’s Search for Meaning: The classic tribute to hope from the Holocaust, London: Rider.